The Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) establishes China’s lasting model of imperial order and imposes a new national consciousness that survives today among the Chinese, who still refer to themselves as the “Han people.” Luoyang, the second Han capital, is not only one of the largest cities in the ancient world but also an international marketplace along the well-traveled trade routes that link East Asia and the West. Political turmoil follows the decline of the Han dynasty as numerous rulers vie for control of China’s vast territory. Under pressure from northern tribes, the Han regimes are forced south, and for 300 years China is divided between northern and southern dynasties. Buddhism takes hold, and Buddhist imagery enters the artistic vocabulary. Calligraphy and painting flourish in the south. The period—and the world—is enriched by the development of paper, which is widely used in China by the third century A.D.

China, 1–500 A.D.

Timeline

1 A.D.

125 A.D.

125 A.D.

250 A.D.

250 A.D.

375 A.D.

375 A.D.

500 A.D.

Overview

Key Events

-

ca. 1 A.D.

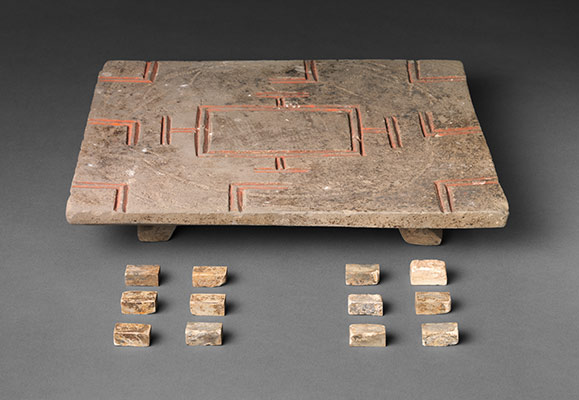

The use of mingqi (spirit goods) as models of soldiers, attendants, entertainers, and other figures expands to include houses, towers, wells, granaries, stoves, and other implements and accoutrements, reflecting the transition from mystical beliefs about the afterlife to a presumption that the activities and pleasures of everyday life continue after death.

-

ca. 25 A.D.

After a brief interregnum, the Han dynasty reestablishes control, ruling from a capital rebuilt at Luoyang, the site of the ancient capital of the earlier Eastern Zhou dynasty. Nearly 500,000 inhabitants are recorded as living in its suburbs, making Luoyang one of the most populated cities in the ancient world. Separate wards are maintained for foreigners, usually traders from other lands.

-

ca. 100 A.D.

Buddhism, which may have reached China earlier, begins to make inroads into Chinese culture. Some of the earliest known Chinese Buddhist images are the carvings on the cliffs at Kungwangshan in Jiangsu Province thought to date to the first or second century A.D. Around 148 A.D., An Qing, better known as Anshigao, an important missionary and translator from Parthia, is active in the Luoyang area ministering to the foreign community and seeking converts at the court.

-

ca. 100 A.D.

Fragments of pure rag paper are known from as early as the second century B.C., but the earliest extant example of hemp paper with writing on it dates to around 109 A.D. Cai Lun (died 121 A.D.), director of the imperial workshops, helps develop a method of mass-producing paper from tree bark, hemp, and linen. By the third century A.D., paper is widely used in China, replacing bamboo, wood, and silk slips. The use of paper spreads to Korea and Japan in the seventh century, and reaches Europe, most likely through Central Asia or Arab intermediaries, in the twelfth century.

-

ca. 200 A.D.

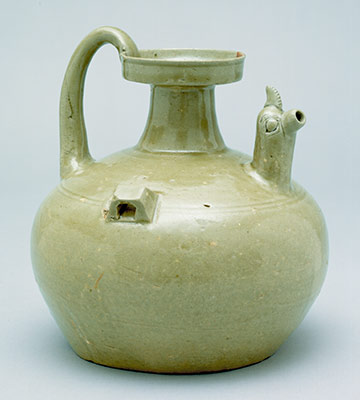

Ceramic vessels and implements, particularly stoneware with green glazes, begin to replace bronze and lacquer goods. Yue wares, made in the southeastern provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu, are particularly admired for their refined bodies and glazes. They are also noted for the production of ornate burial urns and vessels shaped in the form of frogs, rams, or other animals.

-

ca. 220–589 A.D.

Three-and-a-half centuries of almost incessant warfare follow the collapse of the Han dynasty. During this time, China is fragmented into the Three Kingdoms (Wei, Wu, and Shu, 220–265 A.D.), the Jin dynasty (Western and Eastern, 265–420 A.D.), and the Period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386–589 A.D.), collectively known as the Six Dynasties, as well as the Sixteen Kingdoms (304–439 A.D.). Despite the chaos and instability characterizing the era, the Three Kingdoms period is now fondly remembered as one of chivalry and romance. The Sanguo zhi yanyi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms), published by Luo Guanzhong in the fourteenth century, remains one of China’s most beloved historical novels. Woodblock prints of famous scenes from this work are popular as New Year’s decorations.

-

ca. 265 A.D.

Sima Jian, a general of the kingdom of Wu, briefly reunites China under the rule of the Western Jin dynasty. Internal tensions and pressures from northern tribes such as the Xiongnu and the Xianbei eventually force the Han Chinese south of the Yangzi River, where a minor prince gathers the court together and establishes the Eastern Jin in 317 A.D. For the next 270 years, China is divided into the northern dynasties governed by non-Han rulers and the southern regimes under Han Chinese control. This era is known as the Period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties.

-

317–420 A.D.

The Eastern Jin dynasty, with its capital at Nanjing in Jiangsu Province, sees an extraordinary flowering of the arts and is a seminal period for the development of Chinese literati culture. Major figures include the calligrapher Wang Xizhi (ca. 303–ca. 361), who develops a running grass script with characters described as “light as a floating cloud, vigorous as a startled dragon”; Gu Kaizhi (ca. 346–406), a critic who lays the foundation for figure painting; and the revered poet Tao Qian (also known as Tao Yuanming; 365–427).

-

ca. 386 A.D.

During a period of great instability known as the Sixteen Kingdoms, the Tuoba Wei, a branch of the Xianbei, conquer northern China and establish the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534). Their first capital is at Pingcheng near the present-day city of Datong. Unlike the southern rulers who support prosperous monastic estates, the Northern Wei patronizes Buddhism by constructing enormous cave-temple complexes such as that at Yungang (ca. 460–94) near the capital.

-

494 A.D.

Under Emperor Xiaowen (r. 471–99), the Northern Wei capital is moved to Luoyang, a city long acknowledged as a major center in Chinese history. He implements a drastic policy of sinicization, changing artistic styles to reflect Chinese taste and requiring the Xianbei and others to adopt Chinese surnames, speak the language, and wear Chinese clothes. The resentments engendered by these policies contribute to the downfall of the dynasty in the mid-sixth century.

-

ca. 500 A.D.

Xie He, one of the most famous critics in Chinese history, writes the Guhua pinlu (Classification of Ancient Painters), which includes his “six laws” listing desirable attributes for both a work of art and its maker. The “laws” are among the most analyzed and discussed statements in Chinese painting history.

Citation

“China, 1–500 A.D.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=05®ion=eac (October 2000)