At the start of this period, the region is fragmented into city-states dominated by Venice and Milan, two great rivals whose territorial holdings extend over much of northern Italy (with frequently changing boundaries). Even after peace is established between the two at Lodi in 1454, political strife continues through the sixteenth century, as the area is subject to invasion by foreign powers intent on possession of Milan and parts of the Venetian terra firma. Meanwhile, to preserve their own authority, city-states frequently form alliances with and against each other, often with papal or imperial support.

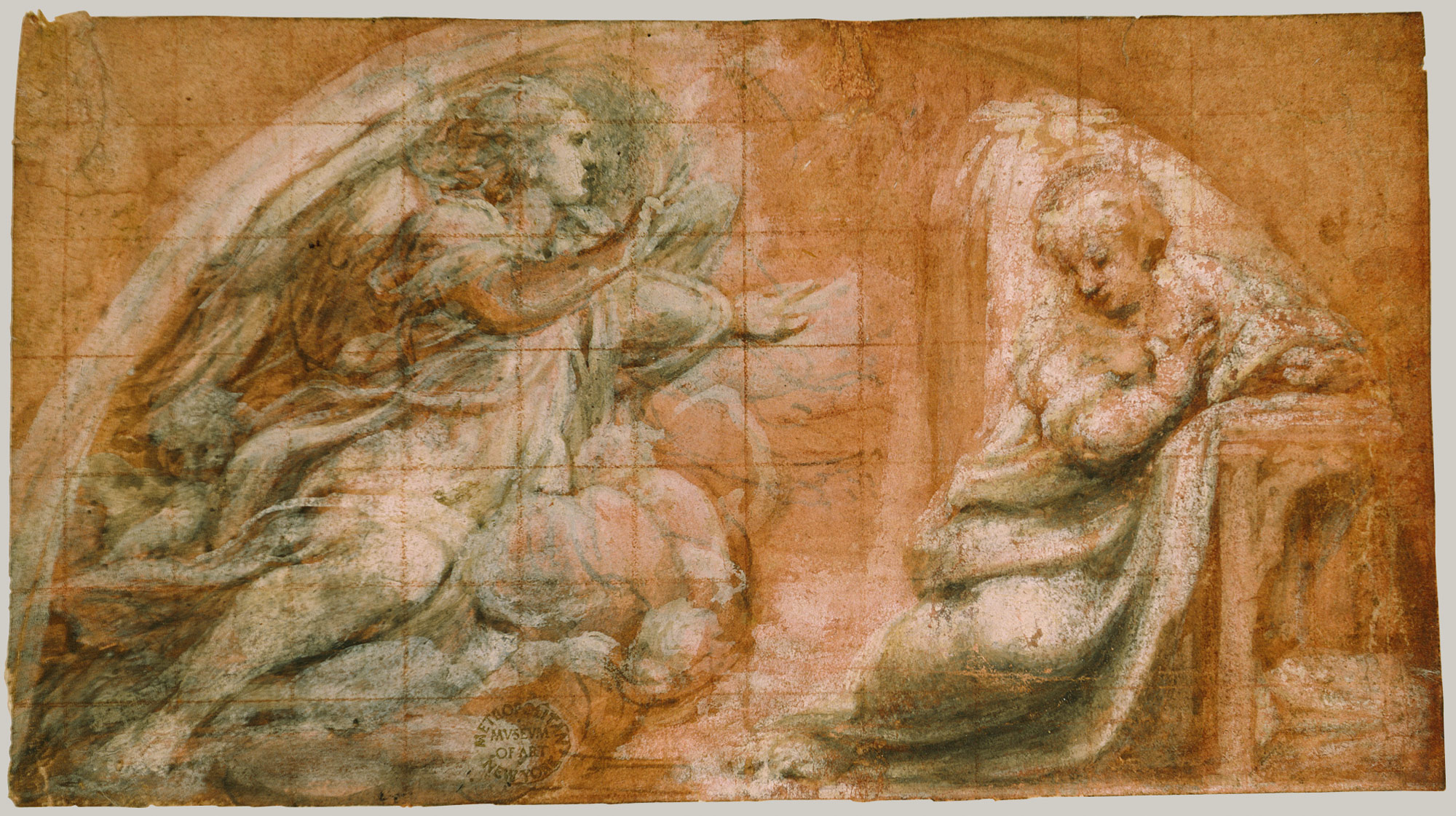

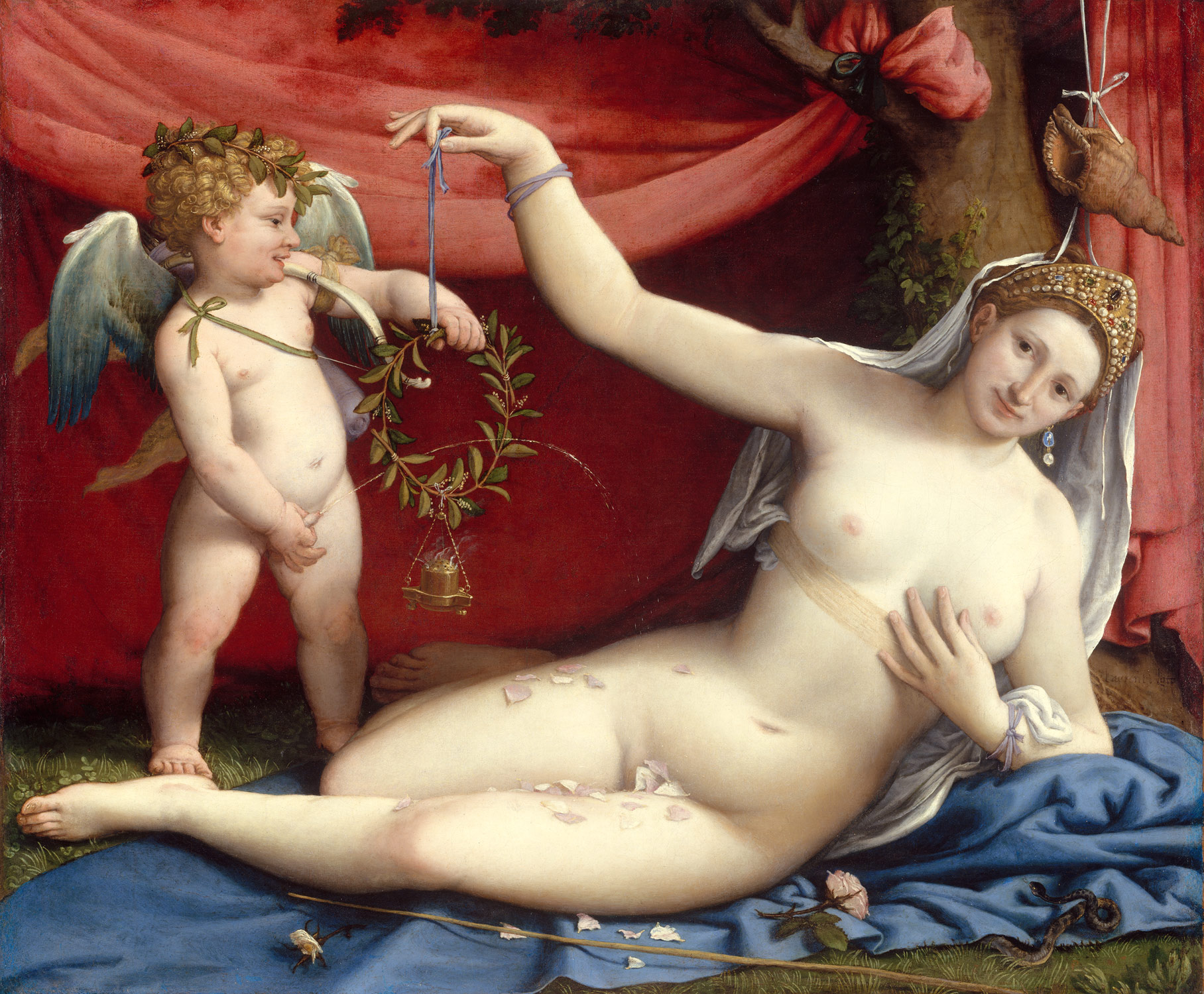

The Renaissance ideals that prevail in central Italy by the turn of the fifteenth century take root in the north by mid-century. Painting, architecture, and the liberal arts flourish at the courts of noble rulers such as the Sforza in Milan, the Gonzaga in Mantua, and the Este in Ferrara. Above all, however, Venice is home to a celebrated school of painting and many of the greatest masters of the period.