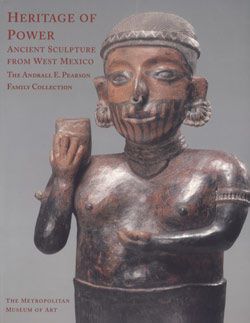

Standing ballplayer

The Mesoamerican ballgame was central to communal, social, and ritual activities throughout the region, with iterations of the sport still played today. Images of the game were created as early as the first millennium. Life-like depictions of both the game and players appear in the ceramic sculptures of the Ameca-Etzatlán region of Jalisco, a state on the west coast of Mexico (see also: 2005.91.1). This figure wields the large ball with fingers held apart, as if about to set it in play at the start of the game. Although appearing ready to compete, he does not wear any of the typical protective ballgame gear. Instead, he is dressed in a hand modeled woven or leather cap, ear flares, and a beaded armband and shoulder markings suggestive of high social status. Traces of red pigment are evident around the ballplayer's neck, and black paint accentuates decorative details of face paint, possibly indicating his ferocity. A flat band of clay around his waist, painted black, is used to depict a loincloth, woven attire more commonly used in daily life.

The game was played using a solid ball made of rubber, a durable plant polymer widely used throughout the Americas from the Southwestern United States to the Gran Chaco Forest of Argentina (Filloy Nadal 2001: 21, Stern 1966: 4–5). Ballcourts, made of limestone, varied greatly in size and configuration. Some were constructed in residential areas with simple aisles while others were in ceremonial plazas with endzones forming a “T” or “I”-shaped playing field and vertical or sharply angled walls for public spectatorship. Although the rules of the game varied across Mesoamerica, Spanish chroniclers from the sixteenth century documented Mexica (Aztec) players using their upper arms and thighs to forcefully strike the ball. The stakes could be dire in this sport, resulting in a vigorous game of life or death corresponding to the movements of the gods and celestial bodies.

The ceramic sculptures of Jalisco were used as funerary offerings in the tombs of members of important families. It is theorized that ballplayer sculptures were meant to accompany the burials of skilled players. This figure holds up the rubber ball commandingly high as others would await his next move, likely demonstrating his authority within the dynamic sport and an indelible memorialization of his victory through clay in the afterlife.

Brandon Agosto, 2024

Further Reading

Beekman, Christopher S., and Robert A. Pickering. Shaft Tombs and Figures in West

Mexican Society: A Reassessment. Tulsa: Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, 2016.

Earley, Caitlin C. “The Mesoamerican Ballgame.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mball/hd_mball.htm (June 2017)

Filloy Nadal, Laura. “Rubber and Rubber Balls in Mesoamerica,” In: The Sport of life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame, pp. 20-31, edited by E. Michael Whittington, London: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Leyenaar, Ted J. J. Ulama: The Perpetuation in Mexico of the pre-Spanish ball game Ullamaliztli. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1978.

Miller, Mary E. “The Ballgame,” Record of the Art Museum Princeton University, Vol. 48, no. 2, (1989): 22-31.

Scarborough, Vincent L., and David R. Wilcox (Eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1991.

Stern, Theodore. The Rubber-Ball Games of the Americas. Monographs of the American Ethnological Society, 17, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966.

Uriarte, María Teresa. “Unity in Duality: The Practice and Symbols of the Mesoamerican Ballgame,” In: The Sport of life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame, pp. 40–49, edited by E. Michael Whittington, London: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.