Saint Tarcisius

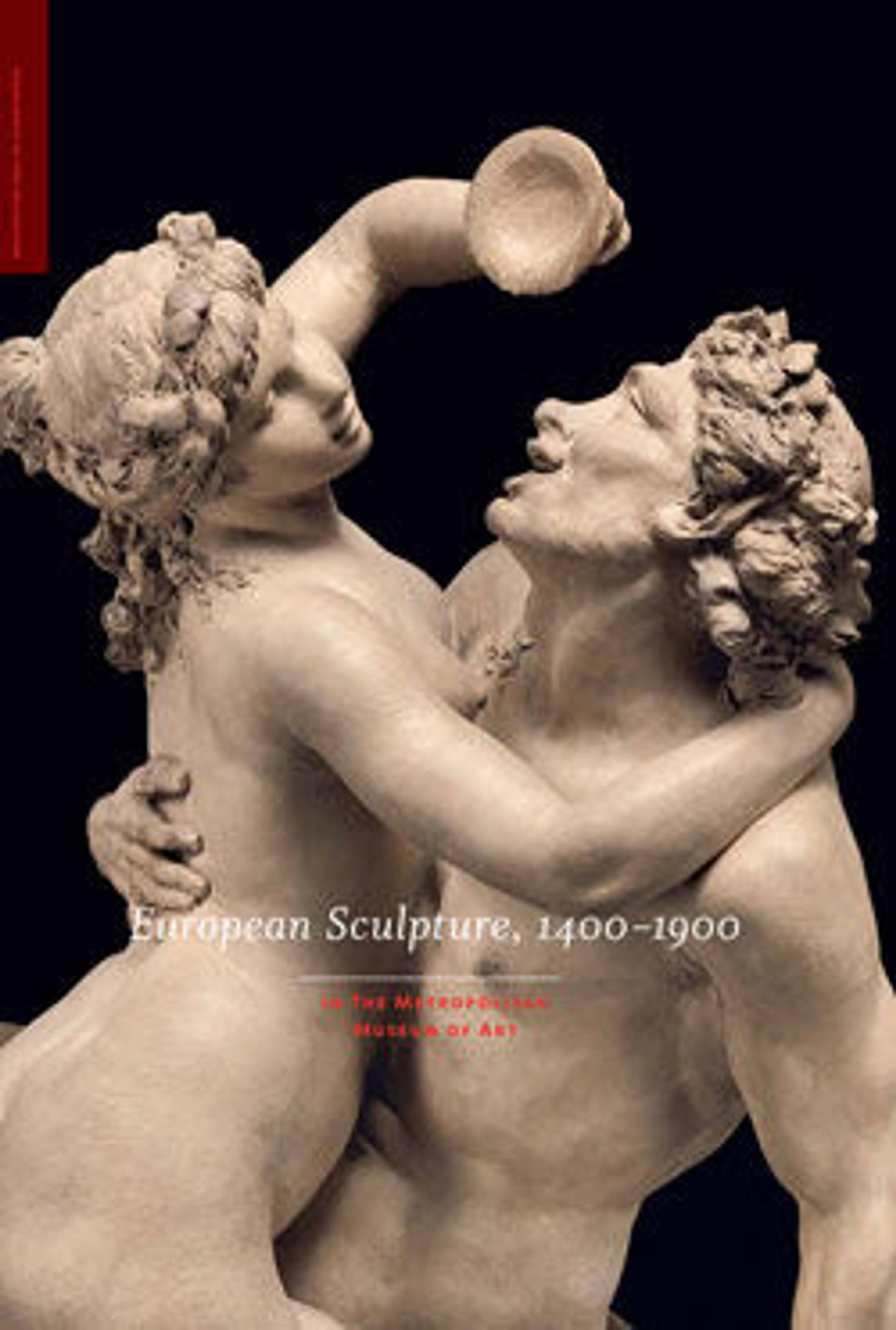

Toulouse-born alexandre falguière found wide acceptance as a sculptor in Second Empire Paris, receiving numerous commissions for monuments to be erected in public buildings and squares. Official success came early. He won the Prix de Rome in 1859 and studied at the Académie de France à Rome until 1865.[1] Winner of the Cockfight, his required submission piece to the Salon, was exhibited in Paris in 1864. Although in its subject — the diversions of Italian peasant boys — it followed a tradition established by Falguière’s early master François Rude and his fellow student at the academy, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, its earthy realism was criticized in some quarters; however, this did not prevent the French government from ordering a bronze version (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). The sculpture that solidified his reputation, however, was Saint Tarcisius, the plaster version of which Falguière exhibited at the Salon of 1867, after his return from Italy. Again, the government supported him, purchasing the plaster and commissioning a marble version (Musée d’Orsay), which won the medal of honor at the Salon of 1868. Even Carpeaux’s Ugolino and His Sons (no. 84) did not receive the same full measure of official esteem that Saint Tarcisius did, since the state ordered only a bronze and not a marble of it.[2]

Although Falguière’s marble of this Early Christian subject appears idealized, his model was a real Italian boy. A photograph in the artist’s collection (fig. 65) shows him coaxed into a histrionic swoon, a sheet draped over his recumbent body. For the finished work, Falguière stretched and smoothed the cloth to emphasize the body’s curves. During his stay in Rome, when he may have first conceived the subject, he obviously saw the famous Baroque sculpture by Stefano Maderno of another early Christian martyr, Saint Cecilia (1600, church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere). By repute, that statue depicts the saint lying in the same position as her body was when it was discovered, and the poignant simplicity of the marble rendering of its subject was an example a nineteenth-century sculptor could not ignore.

Outside of cemeteries, recumbent statues of male youths are rare. James Draper has noted that François-Joseph Bosio’s The Wounded Hyacinth (1817, marble, Musée du Louvre, Paris) is similarly posed, with one knee drawn forward and the torso raised on the elbows.[3] Pierre-Jean David d’Angers’s sculpture of the young Revolutionary hero Joseph Bara lying dead (1838, plaster model, Galerie David d’Angers, Angers) was well known, and Jacques-Louis David’s painting of the same subject (1794, Musée Calvet, Avignon) was famous. Any one of those works may have inspired Falguière, who himself acknowledged the influence of a contemporary sculpture, Carpeaux’s Ugolino and His Sons. The young son to the left in Carpeaux’s composition, a figure that the artist added to heighten the pathos of the scene late in the design process, was certainly a model for Saint Tarcisius.

Early Christian subjects gained popularity in the mid-nineteenth century. In Falguière’s case, a widely read contemporary novel inspired him: Cardinal Wiesman’s Fabiola, or the Church of the Catacombs, which was published in Rome in 1854, a few years before Falguière arrived there. In the book, Wiesman gives an account of a Roman boy named Tarcisius, an acolyte in the early Christian church, who was attacked by jeering pagans on the Appian Way as he carried the eucharistic bread from the catacombs to condemned prisoners in the city. As the inscription on this marble makes clear, the youth chose to die rather than surrender the host to unbelievers. A scattering of stones by his right side and the welt on his forehead are evidence of his martyrdom. With hands crossed over the host, closed eyes, and a yearning expression, Saint Tarcisius struck a chord with the public. In the first version, the inscription is contained in a tabletlike rectangle on the side of a pyramidal base. In the second version, the sculpture now in the Museum, which Falguière kept for himself (or failed to sell), the letters of the inscription are scratched rudely into the blue-tinged marble, carved to simulate the rough paving stones of the Appian Way. This and other variations — the arrangement of the stones, the lowered hips, the absence of decoration on the host — signal that this is not merely a copy but a revision. Pointing marks on the marble show how and where these changes were made.

Footnotes

1. The inscription on the top of the base translates as: "While Saint Tarcisius was carrying the Blessed Sacrament of Christ, a band of thugs demanded that he relinquish it into their profane hands. However, thrown to the ground, he preferred to give up his own life rather than relinquish the celestial body to enraged dogs."

2. Janson 1985, p. 153, notes that it was Saint Tarcisius that made Falguière’s reputation and compares its reception to that of Ugolino and His Sons.

3. Report in the curatorial files, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum.

Although Falguière’s marble of this Early Christian subject appears idealized, his model was a real Italian boy. A photograph in the artist’s collection (fig. 65) shows him coaxed into a histrionic swoon, a sheet draped over his recumbent body. For the finished work, Falguière stretched and smoothed the cloth to emphasize the body’s curves. During his stay in Rome, when he may have first conceived the subject, he obviously saw the famous Baroque sculpture by Stefano Maderno of another early Christian martyr, Saint Cecilia (1600, church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere). By repute, that statue depicts the saint lying in the same position as her body was when it was discovered, and the poignant simplicity of the marble rendering of its subject was an example a nineteenth-century sculptor could not ignore.

Outside of cemeteries, recumbent statues of male youths are rare. James Draper has noted that François-Joseph Bosio’s The Wounded Hyacinth (1817, marble, Musée du Louvre, Paris) is similarly posed, with one knee drawn forward and the torso raised on the elbows.[3] Pierre-Jean David d’Angers’s sculpture of the young Revolutionary hero Joseph Bara lying dead (1838, plaster model, Galerie David d’Angers, Angers) was well known, and Jacques-Louis David’s painting of the same subject (1794, Musée Calvet, Avignon) was famous. Any one of those works may have inspired Falguière, who himself acknowledged the influence of a contemporary sculpture, Carpeaux’s Ugolino and His Sons. The young son to the left in Carpeaux’s composition, a figure that the artist added to heighten the pathos of the scene late in the design process, was certainly a model for Saint Tarcisius.

Early Christian subjects gained popularity in the mid-nineteenth century. In Falguière’s case, a widely read contemporary novel inspired him: Cardinal Wiesman’s Fabiola, or the Church of the Catacombs, which was published in Rome in 1854, a few years before Falguière arrived there. In the book, Wiesman gives an account of a Roman boy named Tarcisius, an acolyte in the early Christian church, who was attacked by jeering pagans on the Appian Way as he carried the eucharistic bread from the catacombs to condemned prisoners in the city. As the inscription on this marble makes clear, the youth chose to die rather than surrender the host to unbelievers. A scattering of stones by his right side and the welt on his forehead are evidence of his martyrdom. With hands crossed over the host, closed eyes, and a yearning expression, Saint Tarcisius struck a chord with the public. In the first version, the inscription is contained in a tabletlike rectangle on the side of a pyramidal base. In the second version, the sculpture now in the Museum, which Falguière kept for himself (or failed to sell), the letters of the inscription are scratched rudely into the blue-tinged marble, carved to simulate the rough paving stones of the Appian Way. This and other variations — the arrangement of the stones, the lowered hips, the absence of decoration on the host — signal that this is not merely a copy but a revision. Pointing marks on the marble show how and where these changes were made.

Footnotes

1. The inscription on the top of the base translates as: "While Saint Tarcisius was carrying the Blessed Sacrament of Christ, a band of thugs demanded that he relinquish it into their profane hands. However, thrown to the ground, he preferred to give up his own life rather than relinquish the celestial body to enraged dogs."

2. Janson 1985, p. 153, notes that it was Saint Tarcisius that made Falguière’s reputation and compares its reception to that of Ugolino and His Sons.

3. Report in the curatorial files, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum.

Artwork Details

- Title:Saint Tarcisius

- Artist:Alexandre Falguière (French, Toulouse 1831–1900 Paris)

- Date:ca. 1880

- Culture:French, Paris

- Medium:Marble

- Dimensions:Overall (confirmed): H. 23 1/2 x W. 52 x D. 20 in. (59.7 x 132.1 x 50.8 cm)

- Classification:Sculpture

- Credit Line:European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Fund, 2007

- Object Number:2007.407

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.