The Human Connection was on view in Gallery 132 from Nov. 4, 2022 to Nov. 26, 2023. See all photographs featured in the installation here.

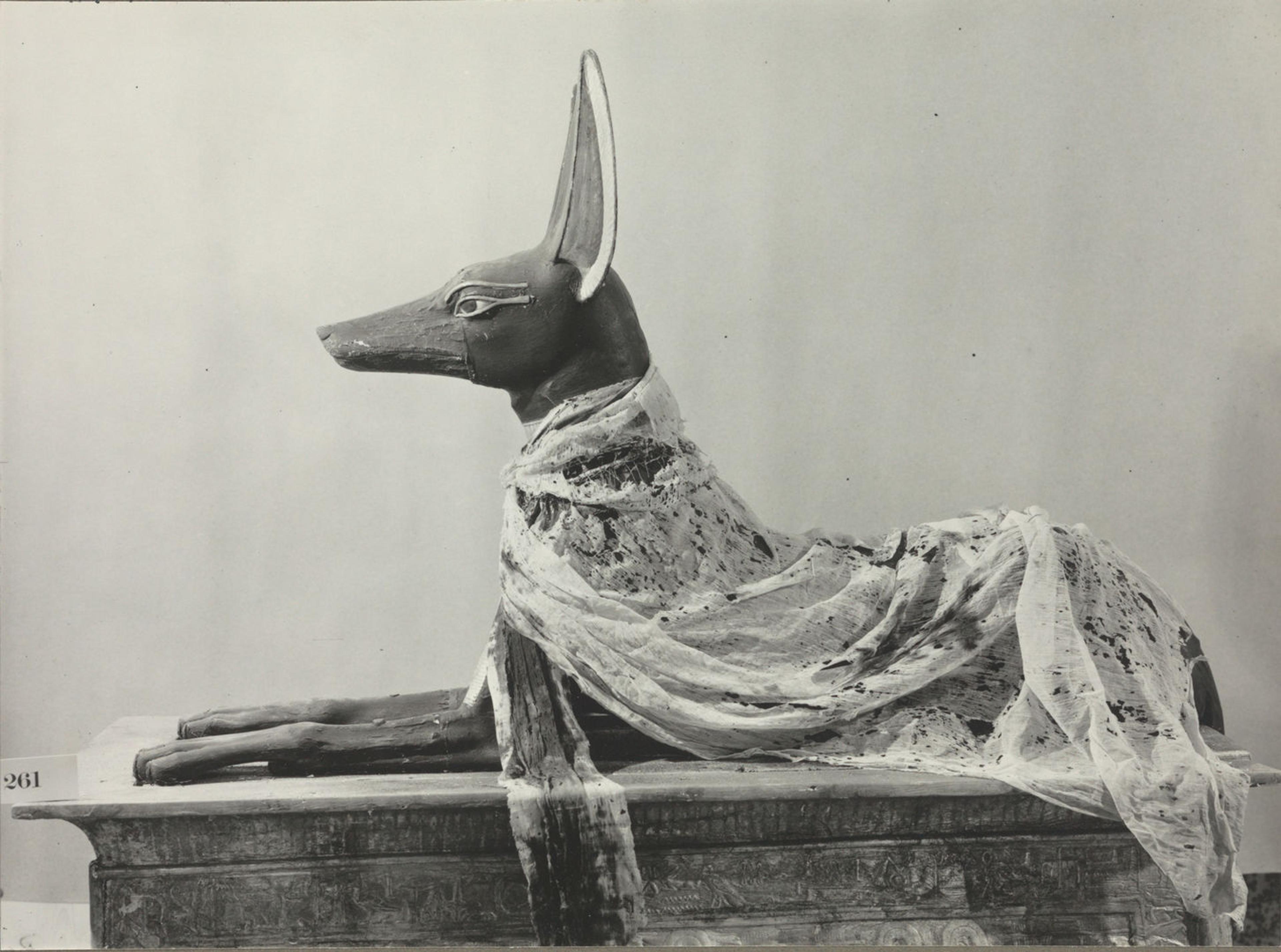

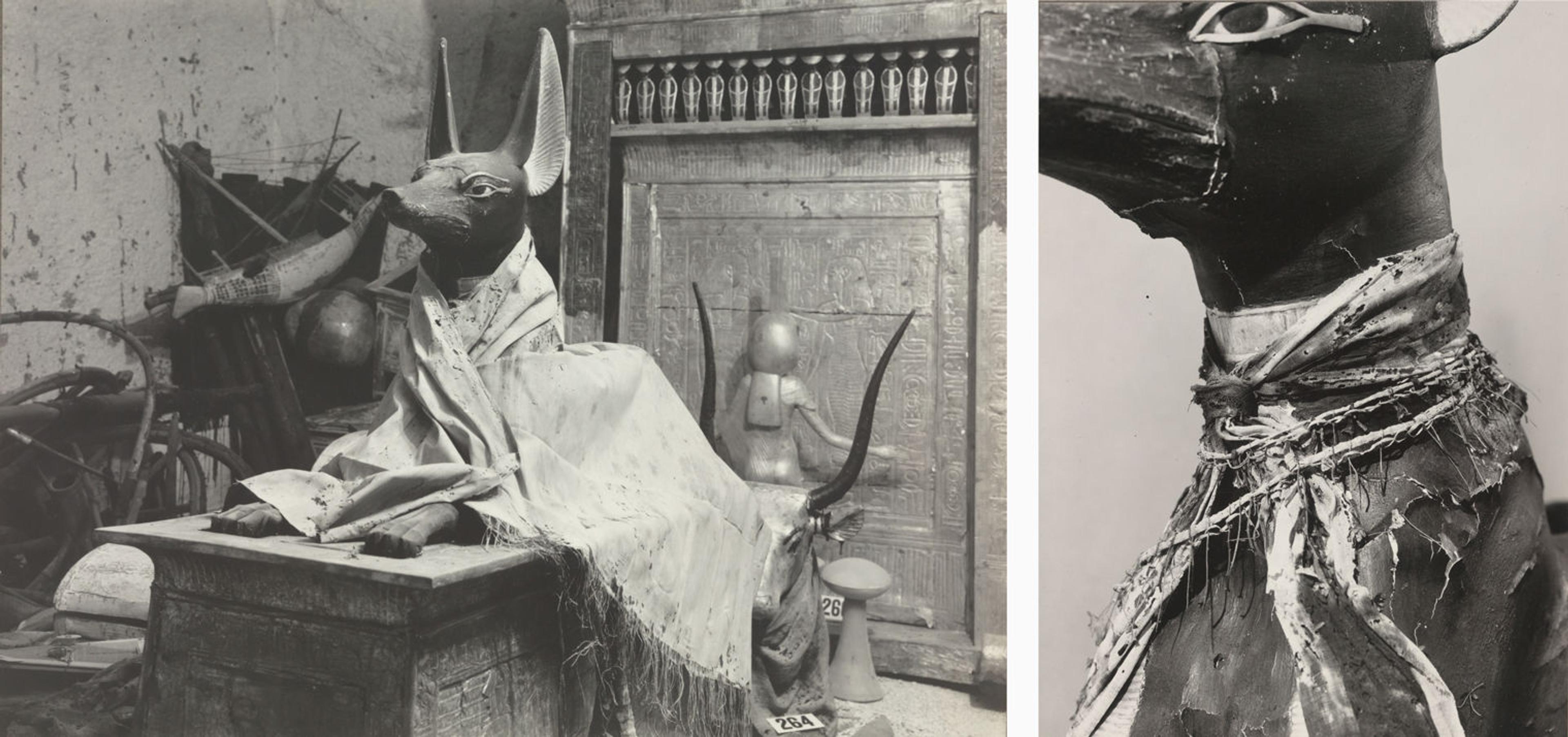

Harry Burton (British, 1879–1940). Textiles draped over Anubis figure, 1926. Gelatin silver print. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 94)

When people hear the name Tutankhamun, they usually think of the power and riches of the pharaoh and less of the person who lived over 3,000 years ago or of human acts that happened for his funeral. The current installation of photographs taken by Harry Burton focuses on a more human connection.

Harry Burton working with two Egyptian assistants, whose names were not recorded. In a 1941 letter, Burton’s widow referred to an individual called Hussein who did camera work with her husband and who must be one of the two people here [1]. Luxor, Valley of the Kings, 1920s. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (MM80950)

Burton was a Metropolitan Museum Expedition photographer known for taking superb images under difficult conditions. In fact, when Tutankhamun’s tomb was uncovered in 1922, he was considered the best archaeological photographer in Egypt. Howard Carter, director of the Tutankhamun excavation, therefore requested the services of Burton, who subsequently spent part of 1922–33 documenting the work and the finds. His original gelatin silver prints and glass plate negatives are housed today in The Met’s Department of Egyptian Art Archives and in the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

Burton’s photographs of Tutankhamun’s “golden treasures” are famous, but the current exhibition highlights lesser-known, more intimate images. Among them are pictures of mundane belongings and simple grave goods, which were used by non-royal people as well and provide a more personal glimpse of the king. Also featured are photographs that show the use of textiles and plants for the burial, which bring us closer to some of the human acts that took place over three thousand years ago.

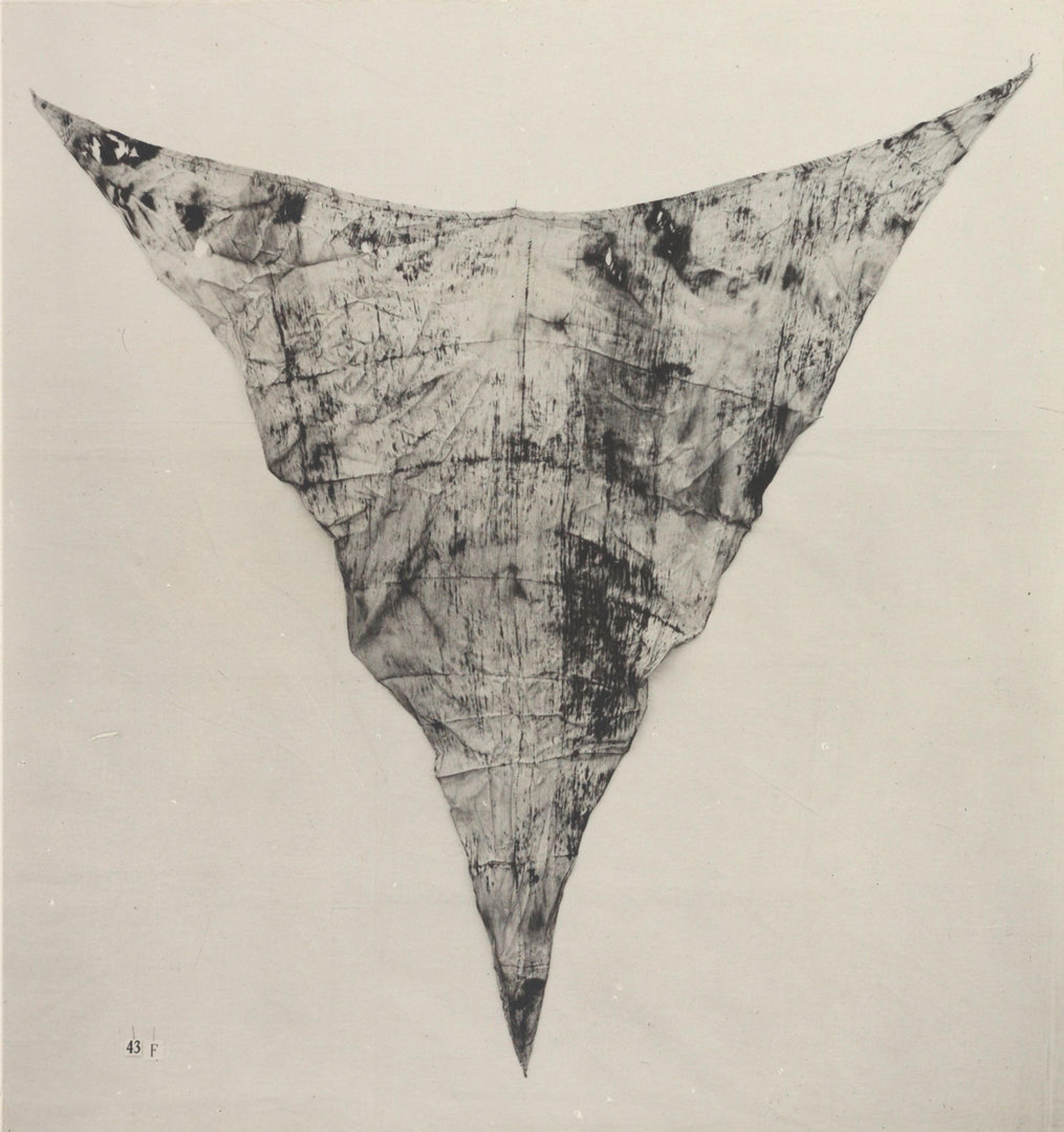

Harry Burton, Loincloth, 1923–25. Gelatin silver print. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 809)

Within the tomb were, for example, many boxes that contained folded clothing, including over 140 loincloths. The example here was laid out for Burton’s photograph and still shows visible creases where it had been folded. When in use, two ends of these triangular-shaped pieces were wrapped around the hips while the third end was pulled through the legs towards the front, where all three were tied. People of all classes wore this ordinary article of clothing, either alone or beneath other garments. As part of the pharaoh’s wardrobe, it was probably his underwear!

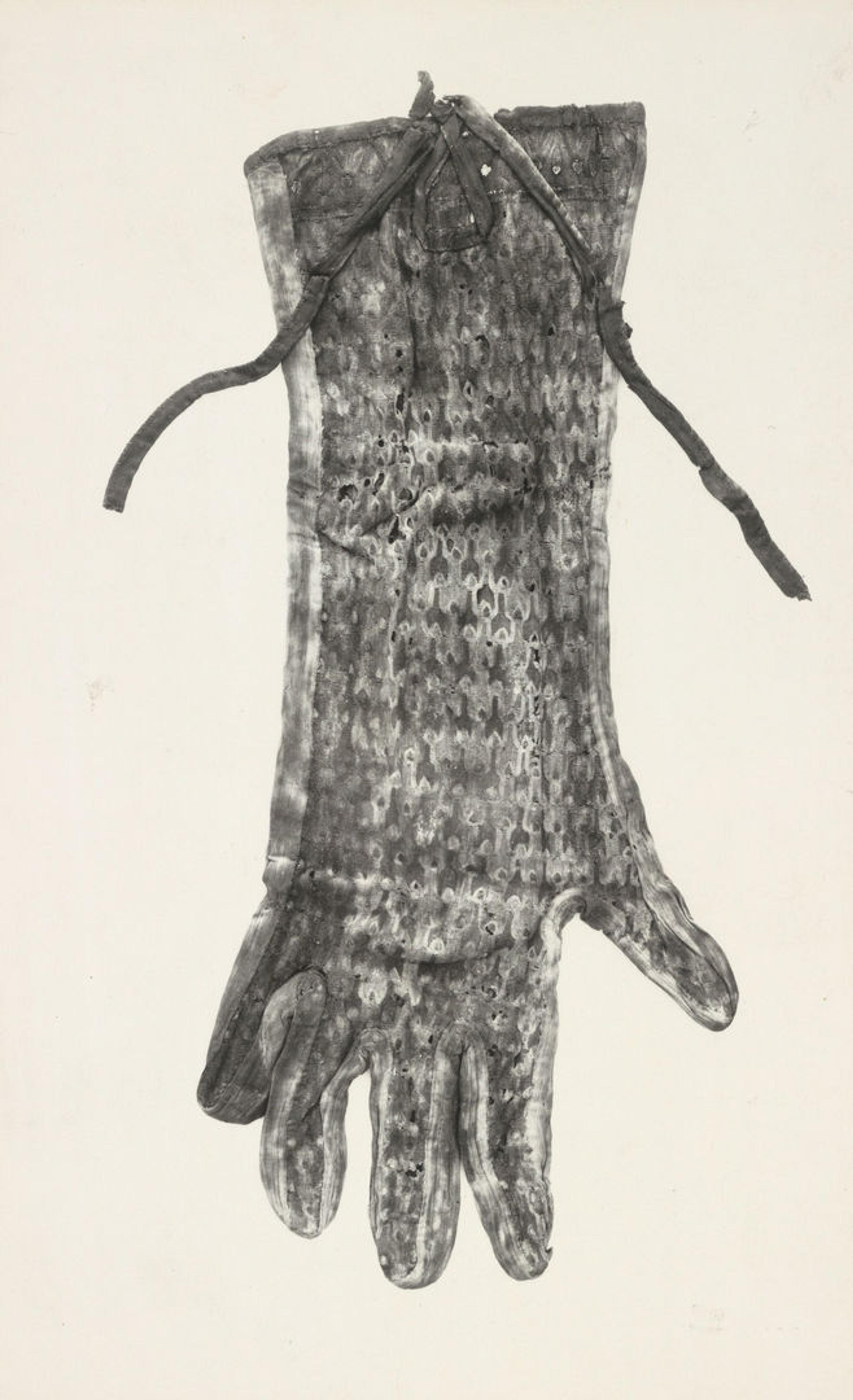

Harry Burton, Adult-sized glove, 1927–30. Gelatin silver print. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 821)

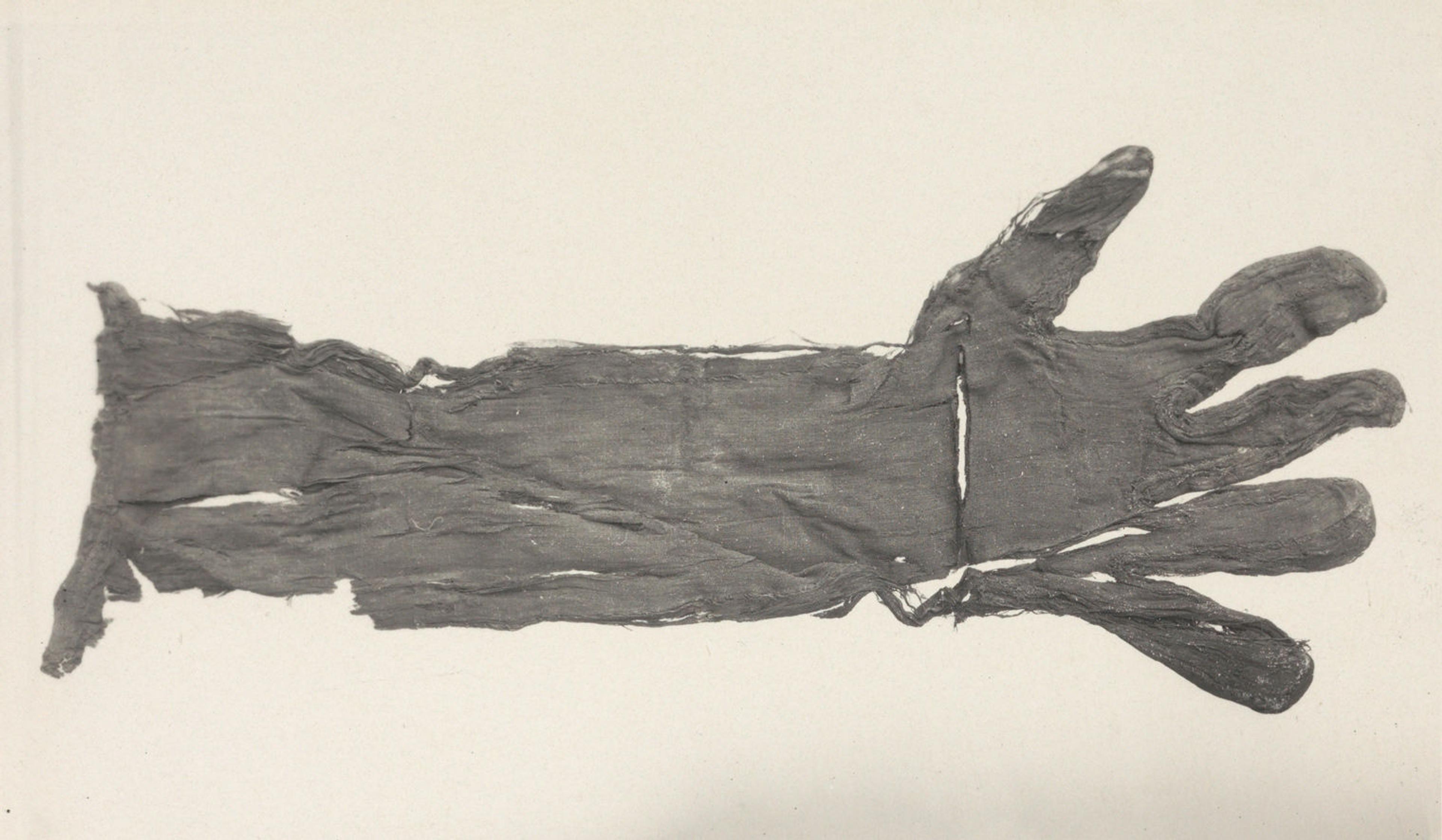

Harry Burton, Child-sized glove, 1923–25. Gelatin silver print. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 807)

Tutankhamun became pharaoh when he was a child and died as an adolescent or very young man. Several of the types of clothing found in his tomb, such as loincloths and gloves, came in various sizes. Illustrated above are Burton’s photographs of an intricate adult-size glove with a tie and a child-size glove. The garments that were in the tomb are pieces he probably owned and may have worn during his life. While we do not know what Tutankhamun was like, seeing some of his personal belongings helps us to think of him as a person and not just as a king.

Harry Burton, Flame-making implement, 1927–30. Gelatin silver print. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 446)

Tutankhamun’s grave goods include objects made specifically for burial as well as many personal belongings, such as tools and weapons. Among them was an odd-looking instrument that once inspected turns out to be a cleverly devised flame-making implement, like an ancient version of a box of matches! A small drill could be inserted into one of the circular nooks filled with resin and friction would create a flame.

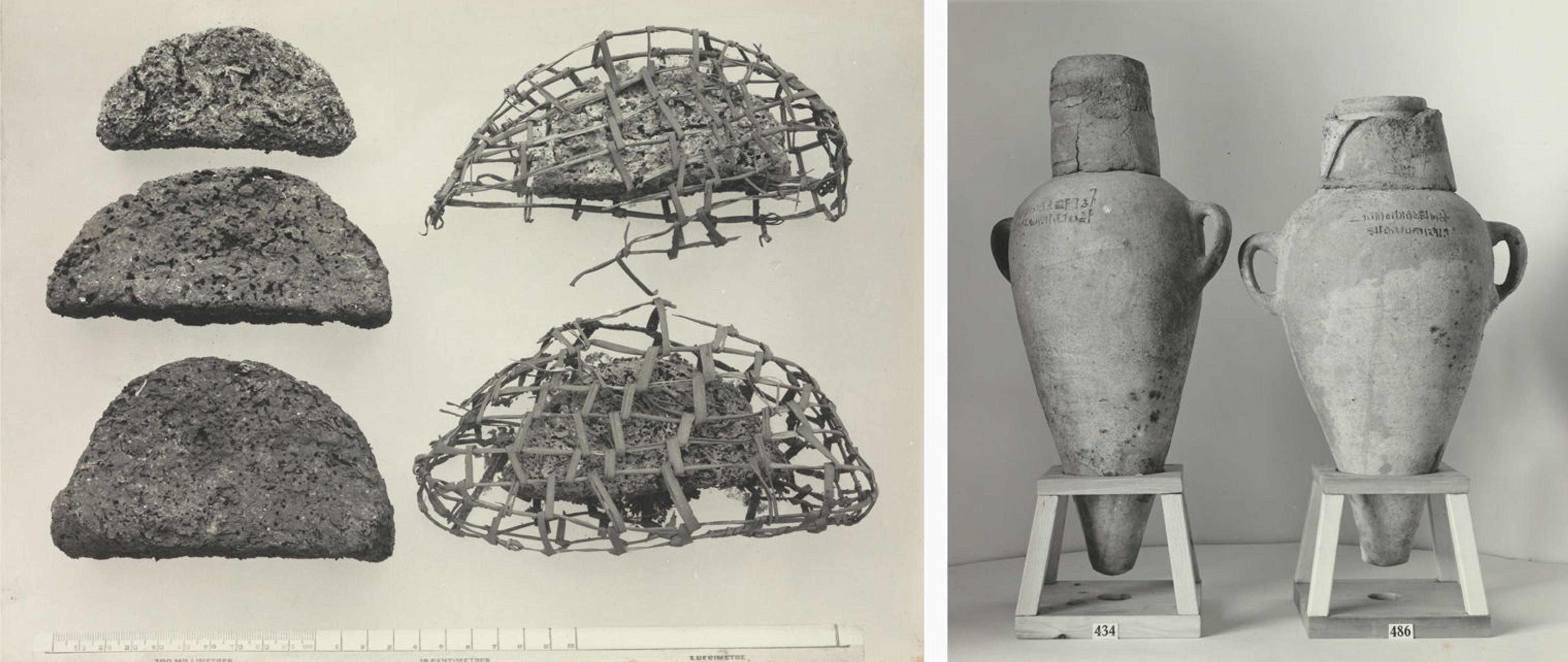

Harry Burton, Bread and wine jars, 1927–30. Gelatin silver prints, Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 268, 832)

Food and drink were considered essential for the ancient Egyptian afterlife, and food items were deposited in the tombs of royals and nonroyals alike. Among the actual foodstuffs in Tutankhamun’s tomb were semi-circular bread loaves containing fruits from the Christ’s-thorn plant. Some of the loaves were put in a netlike structure made of rushes that may have been a type of holder, though its purpose is not fully understood.

For Tutankhamun’s afterlife, two dozen wine jars were placed in the tomb. As with wine bottles today, the containers were labeled with the vintage and place of origin; nearly all also include the names of the main vintners. The jars were closed with large mud plugs that were then impressed with seals. Unfortunately, the liquid itself dissipated over time.

Harry Burton, Textiles and garlands draped over Anubis figure, 1926. Gelatin silver prints, Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 92, 96)

Ancient Egyptians draped textiles around objects in deliberate acts, but the results are often no longer visible as the fabrics were removed in modern times in order to expose the objects underneath. Here, Burton documented several layers of linen on a figure of the jackal-headed god Anubis before they were removed by the excavators. The animal’s body was found covered with a large, carefully arranged textile, a repurposed fringed tunic bearing the name of King Akhenaten, who was probably Tutankhamun’s father. Beneath that was a thin shroud (see image all the way above), followed by floral garlands around the figure’s neck. A long piece of cloth had also been draped around the neck like a scarf, trailing downward. This bottommost layer would have been the first step in the sequence of shrouding and garlanding the deity figure.

Harry Burton, Plant bouquet and detail of a plant bouquet, ca. 1923–24. Gelatin silver prints. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 143, 146)

When Tutankhamun was buried, several plant bouquets were deposited in his tomb. More than three thousand years later, the bouquets found inside were in excellent, if fragile, condition. The one on the left here is quite large—more than six feet long. The lower sections of sizable bouquets were bound tightly (as on the right) to create a handle shape that enabled them to be carried, likely in the funeral procession.

Unlike flower garlands that were placed on Tutankhamun’s coffins, these bouquets did not include flowers; they were made primarily of twigs from evergreen Persea plants and olive trees. Ancient Egyptians associated plants and the color green with life, and the arrangements probably signified regeneration and everlasting existence. Similar bouquets were also deposited in the tombs of non-royal people.

Harry Burton, Plant bouquet, ca. 1923–24. Gelatin silver print. Department of Egyptian Art Archives (TAA 145)

The delicate bouquet shown above is much smaller, with a length of about 16 inches. It consists of ten twigs from the Persea tree. Carter observed that one of these twigs had been cut from the branch with a knife, while the others were broken off. Unfortunately we do not know who did so and under which circumstances. If priests indeed carried the large bouquets in the funerary procession, then one wonders, what was the role of the small bouquets? Were these lighter-weight and more easily managed bouquets carried by family members? While we simply do not know, these bouquets encourage us to reflect on the human acts that took place in antiquity, as well as on our own funeral customs today and our shared humanity.

This installation was made possible by the generosity of the Friends of Egyptian Art. It is on view in Gallery 132 from Nov. 4, 2022, to Oct. 31, 2023. See here for the photographs in this installation.

Because the light-sensitive originals from the 1920s cannot be displayed for extended periods, the installation features twenty-nine prints made in 2022 from Burton’s photographs, matching the size and orientation of those in the archive, as well one original print that highlights participants in the excavations and is changed every three months.

Footnotes

[1] As noted by Christina Riggs, in her 2020 publication, Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt, and the Archive (London: Routledge), 169–70.