The preservation of the Temple of Dendur is due in large part to the temple's salvage from the rising waters of the Nile, but the conservation of this monument extends far beyond the temple's relocation. In the period immediately before the arrival and installation of the temple blocks at The Met, a team of conservators, scientists, and curators critically evaluated the appropriate environmental conditions for display, the physical properties of the stone blocks, and options for mechanical and chemical intervention. Interestingly, the conservation and reconstruction of the temple coincided with a period of methodological shifts in the field of monument conservation, including the first international symposium on the deterioration of building stones. As a result, the temple remains an important case study in the history of conservation today.

Documented interest in preserving the temple began a full half-century before the blocks made their way across the Atlantic in 1968. In response to concerns about rising water levels resulting from the construction of the first Aswan Dam (1898–1902), the Egyptian Antiquities Service undertook several campaigns of survey and restoration. These early efforts to restore the Temple of Dendur, under the direction of Alessandro Barsanti, included securing and strengthening some of the blocks with iron cramps and support beams, restoring structurally critical elements using stone and cement, and filling gaps between blocks. Although today we consider iron unsuitable for such applications, since it readily corrodes and expands in the presence of moisture and air, this early treatment likely helped keep the temple intact for several decades.

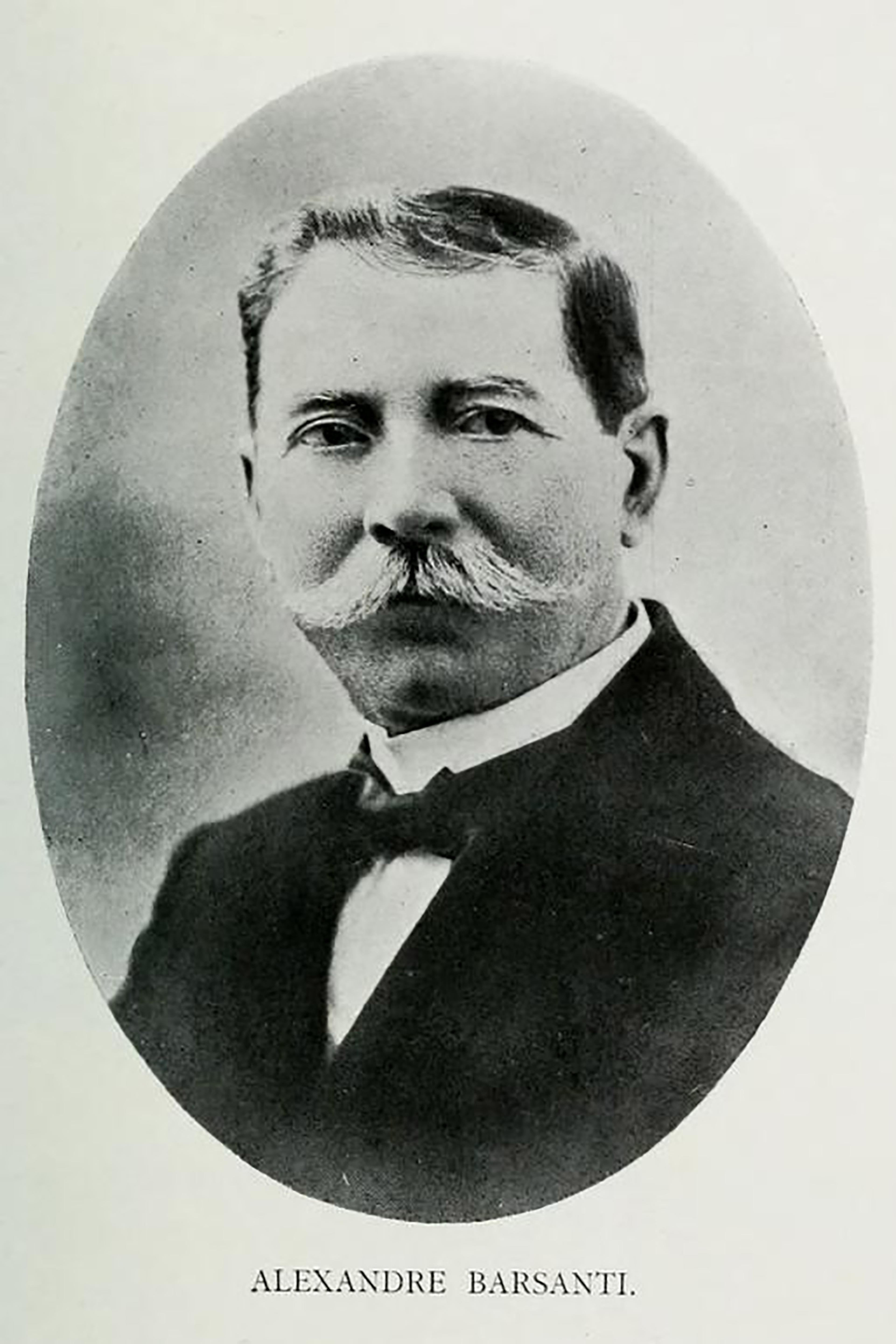

"Alessandro Barsanti," from Annales du Service des antiquités de l'Egypte (ASAE) 17 (1917), unnumbered plate.

When the temple's blocks finally arrived in New York, approximately sixty years later, another major campaign of conservation began. The condition of the blocks was assessed and documented, debris and soiling were removed, and loose fragments were catalogued and collected. Soluble salts were removed from the stone through a campaign of washing using a system of sprinklers, and the wash water was periodically collected for analysis. The biofilm that formed while the blocks were drying was treated with a commercial biocide.

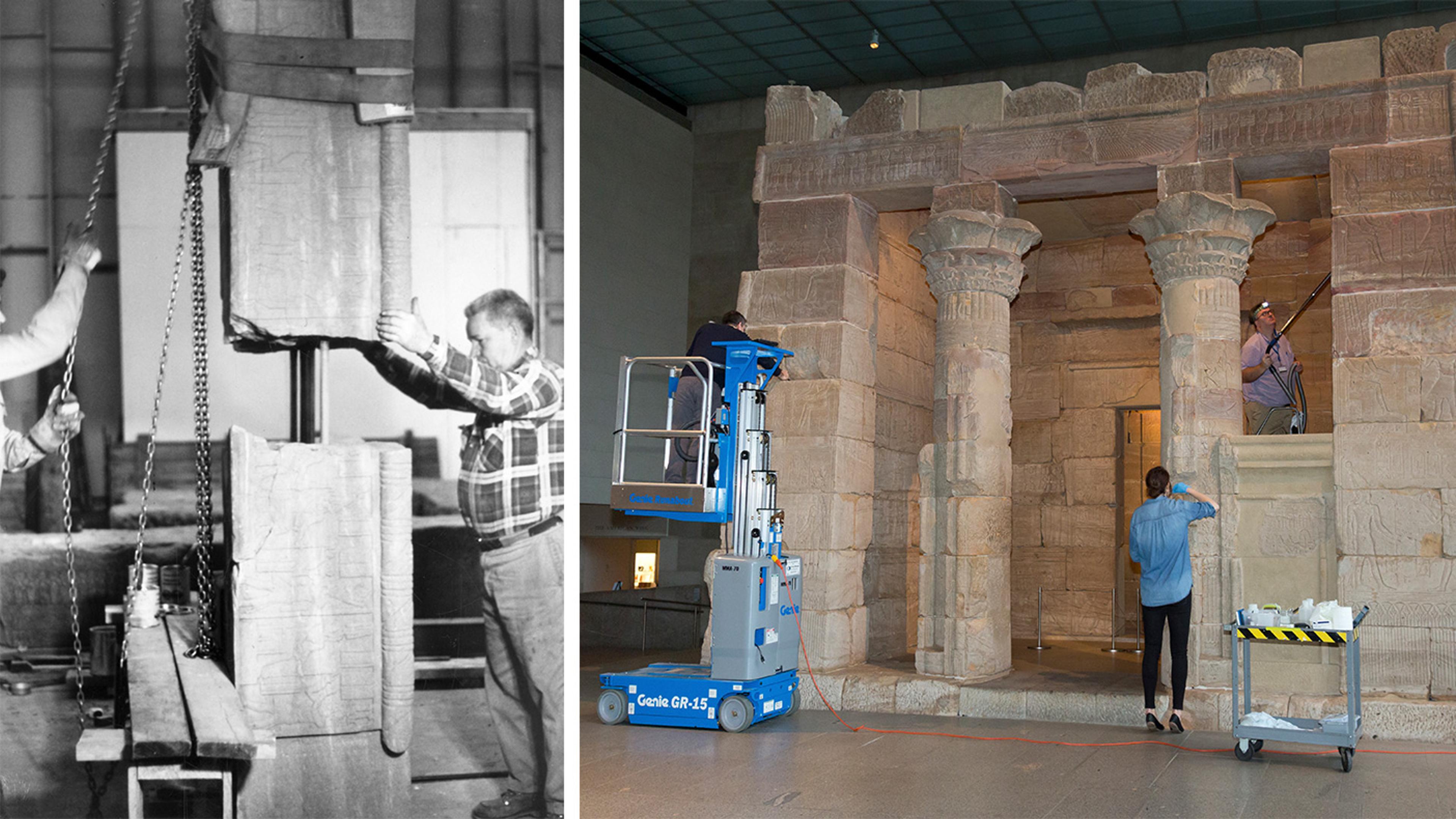

Temple blocks in storage in the Museum's North Parking Garage prior to conservation treatment, early 1970s

At the same time, discussions were underway regarding the overall stability of the temple's blocks and how the structure might be safely reconstructed. Since it had already been established that the temple would be installed in a space with stable temperature and relative humidity, there was little concern that the stones would deteriorate from environmental cycling. Instead, the biggest concern was whether the stones would be mechanically strong enough to withstand the reconstruction process.

To address these questions, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, New York University, and Brookhaven National Laboratory carried out a series of mechanical tests on small samples of Dendur stone, including tests for hardness, crushing, compression, bending, and rupture. Although today these tests are a routine part of such projects, at the time this was a truly innovative approach to evaluating a monument's stability.

Fortunately, the tests showed that most of the stones were strong enough to endure reconstruction, excluding the roof stones and corner stones, which would require some additional support. However, there were also concerns about the mechanical strength of the blocks during the more taxing process of lifting and installation, which led the team to investigate methods to chemically strengthen the stone. Various treatments were considered, including impregnation with experimental monomers and polymers. Ultimately, it was decided that because of the stone's low bending strength, transporting the blocks to an appropriate facility for treatment would pose a greater risk than leaving them untreated.

Two fragments of the temple are joined with steel rods and epoxy

After this research and testing had been concluded, the work of reconstruction began. The corroded iron elements from Barsanti's 1908 restoration were replaced with more stable materials. Broken stones were secured with steel rods; fractured lintels were joined with rolled steel; much of Barsanti's concrete was removed; and losses were filled with mortars specially designed by conservators and scientists. As the blocks were being assembled, setting mortar was applied between each course to help evenly distribute the weight of the blocks and thereby reduce physical stresses.

Over the decades since, the condition of the temple has been regularly assessed by conservators, and happily it has remained generally unchanged. But in preparation for the celebration of the temple's fiftieth anniversary, a second campaign of conservation and research was undertaken by members of the Departments of Egyptian Art and Objects Conservation. The main objectives of this work were to thoroughly assess the condition of the temple's blocks and previous restorations, to photographically document the exterior and interior surfaces of the temple, to remove dust and other particulate matter that had accumulated on the stone surfaces, and remove grease and grime that had built up on blocks that are routinely touched by the public.

Left: Removing dust with soft brushes and low power vacuums. Right: Cleaning grime from handling

Most of the cleaning was done using soft brushes and low-power vacuums, although some follow-up cleaning was done using soft sponges. Examining and cleaning the upper courses of the temple and its gateway required conservators and technicians to work on lifts, which also enabled the documentation of parts of the temple that are not typically accessible.

Doorway block with nineteenth-century graffiti, before and after cleaning

Decades of visitors running their hands over the stone blocks in the entryway to the temple had left a thick film of dark brown grime, and this too was addressed during the recent conservation campaign. This greasy film, which is both unsightly and detrimental to the stone, lodges in between the grains of the porous sandstone, making it difficult to remove. Cleaning was carried out using a combination of mild cleaning solutions. Although some of the oil remains below the surface, the appearance of the doorway blocks has been significantly improved.

Time-lapse video of the temple being cleaned in 2017, in preparation for the celebration of the Temple of Dendur's 50th anniversary. Video by Thomas Ling