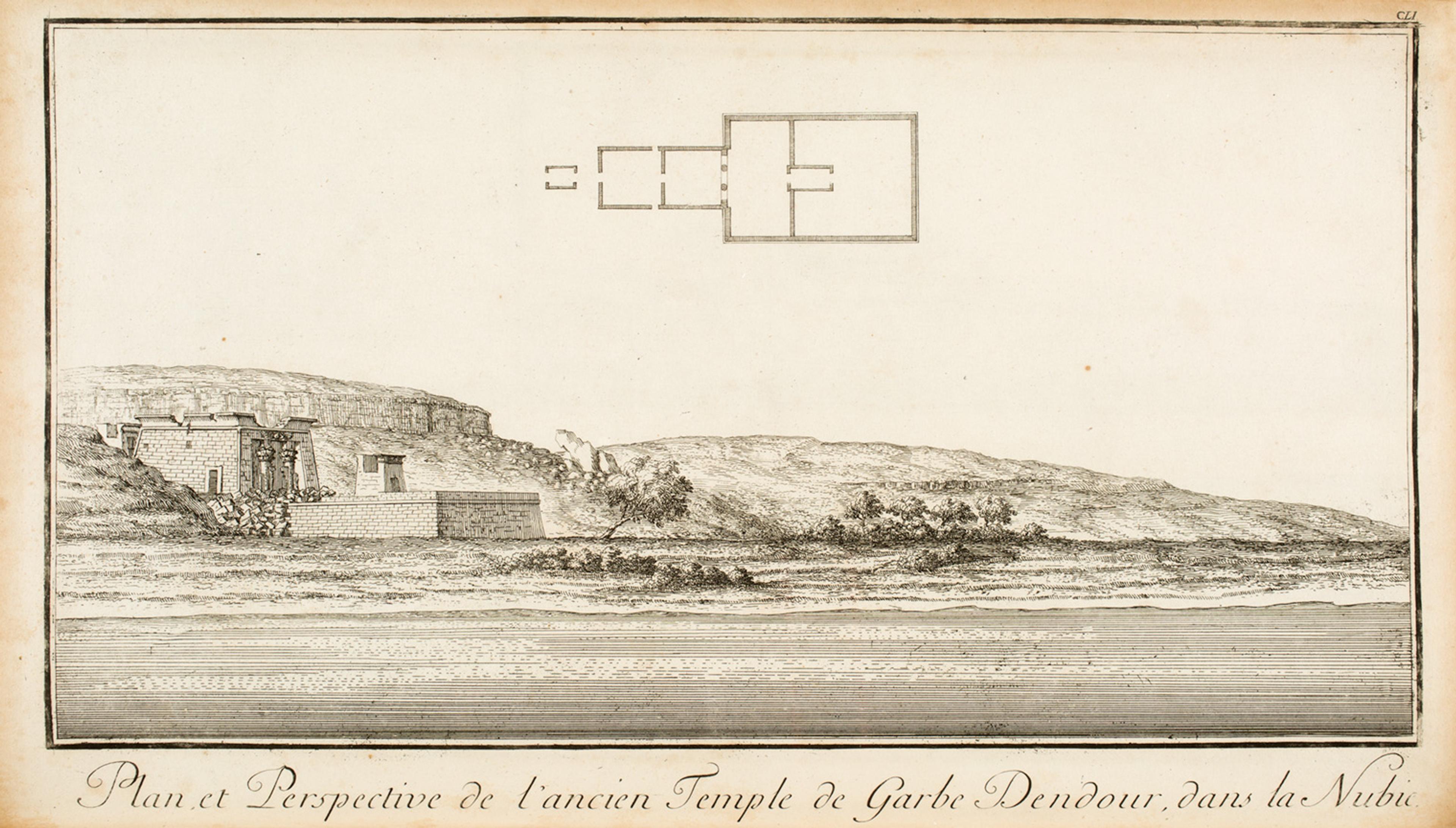

Frederick Lewis Norden, "Plan and perspective of the ancient temple of West Dendur in Nubia," in Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie (Travels in Egypt and Nubia) (London, 1757), plate 151.

Starting in the early eigthteenth century, Europeans who traveled to Egypt illustrated the places they visited by drawing the landscape, people, and ancient monuments. By the mid-nineteenth century, photography had come into use, but it never completely replaced sketches and watercolors as a method to illustrate one's travels. The Museum is fortunate to have, among its vast holdings of books and works of art, numerous images of the Temple of Dendur created by these early travelers.

Frederick Lewis Norden (Danish, 1708–1742)

One of the earliest documentations of a visit to the Temple of Dendur was by Frederick Lewis Norden, a Danish naval officer and explorer. As a cadet preparing to enter the navy, his drawing skills brought Norden to the attention of King Christian VI, who eventually gave him a stipend to study shipbuilding techniques in various European maritime centers. In 1737 Norden received orders from the king to travel in Egypt. At the time, Egypt's ancient culture was known in Europe primarily through ancient Greek and Roman texts. Few contemporary Europeans had visited the country, described its landscape, or made a record of its ancient monuments. The Danish king wanted Norden to document all these things and to make a map of the river for navigation purposes.

Norden arrived in Alexandria in June 1737, proceeded to Cairo, and embarked in mid-November on a voyage up the Nile, traveling as far as el-Derr in Nubia, a region south of Aswan. On the return voyage, he reached the vicinity of the Temple of Dendur on December 30. Before the Aswan High Dam was completed in 1970, the Nile flooded annually between June and September, the hottest months of the year, and most Europeans visited between the months of November and February, which were cooler. As a result, early drawings, paintings, and photographs of Dendur usually show it in a rocky desert landscape, with no reference to the river.

Norden's plan of the temple leaves much to be desired: he omits one room, places the side doors in the wrong position, and ignores the concave curve at the front of the temple's terrace. In his drawing, the gateway is proportionally much too small. But Norden creates a reasonable impression of the temple's desert location against a rocky hillside set well back from the river, which would have been at its lowest level of the year.

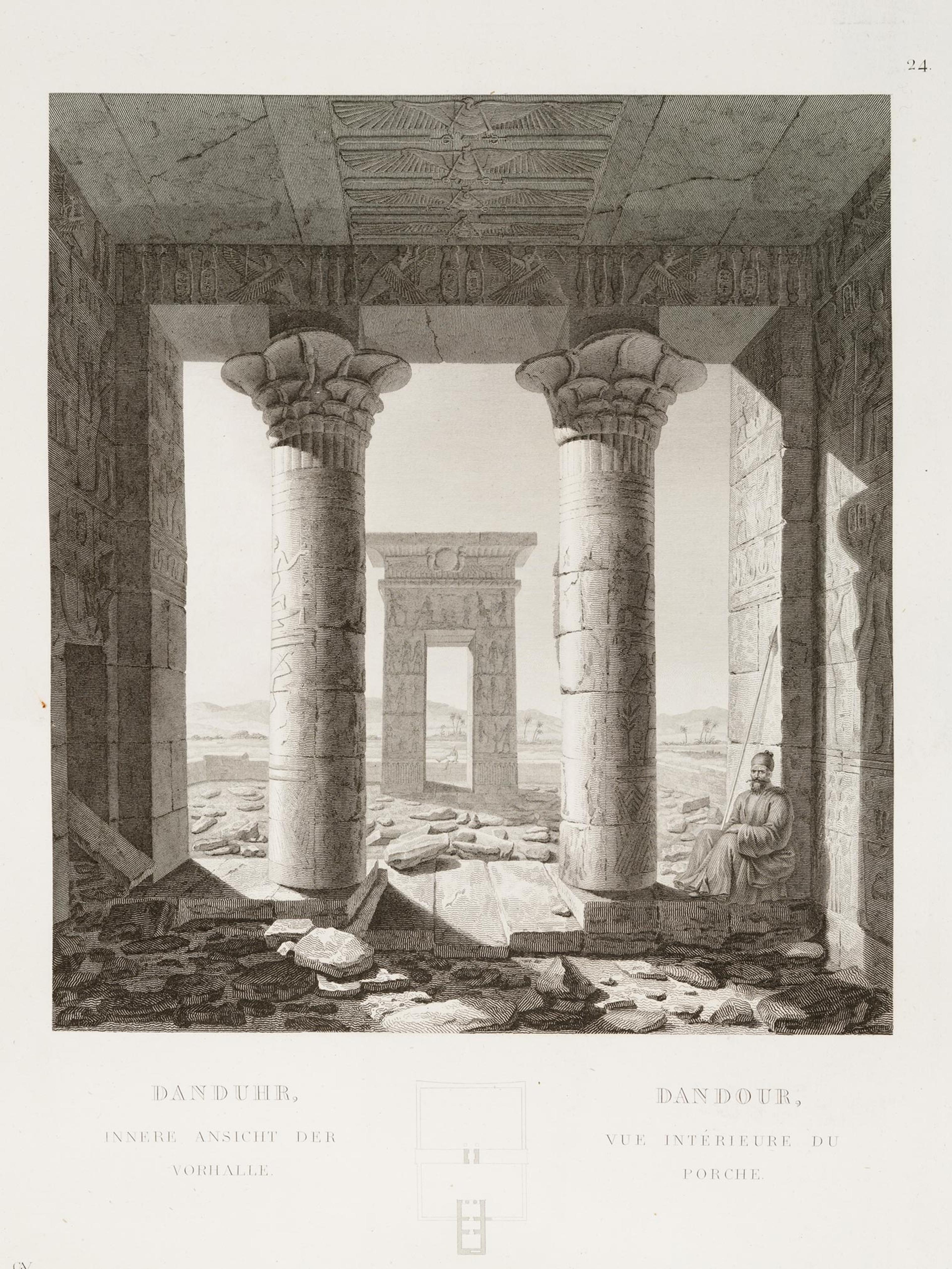

Franz Christian Gau (German, 1789–1853)

Born in Cologne, a German city occupied by Napoleon in 1794, Franz Christian Gau was trained as an architect at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Gau traveled to Egypt in 1818 as a companion to a wealthy gentleman. After parting ways in Alexandria, Gau set off on his own to record the monuments of Nubia that had not been documented by the scholars and artists who had accompanied Napoleon's military expedition some twenty years earlier.[1]

Franz Christian Gau, "Dendur, interior view of the porch," in Antiquités de la Nubie (Stuttgart, 1822), plate 24.

At the end of January, Gau arrived at Dendur, which delighted him with its elegant proportions and simplicity. He proceeded to make remarkably accurate drawings of the decoration and an excellent rendition of the temple and its surrounding landscape.[2] His most unusual drawing shows a view from inside the temple's porch with two figures posed to give a sense of scale: one is seated at the right in the entrance of the porch; the other is just barely visible through the gateway, perched on the parapet at the front of the terrace. The figure in the porch is only about eighty percent life-size, making the temple appear somewhat larger than it is.

Due to his careful measurements of the structure, Gau discovered the hidden cavity in the rear wall where cult objects associated with the two brothers who were worshipped in the temple may have been buried; its location is noted on his plan.

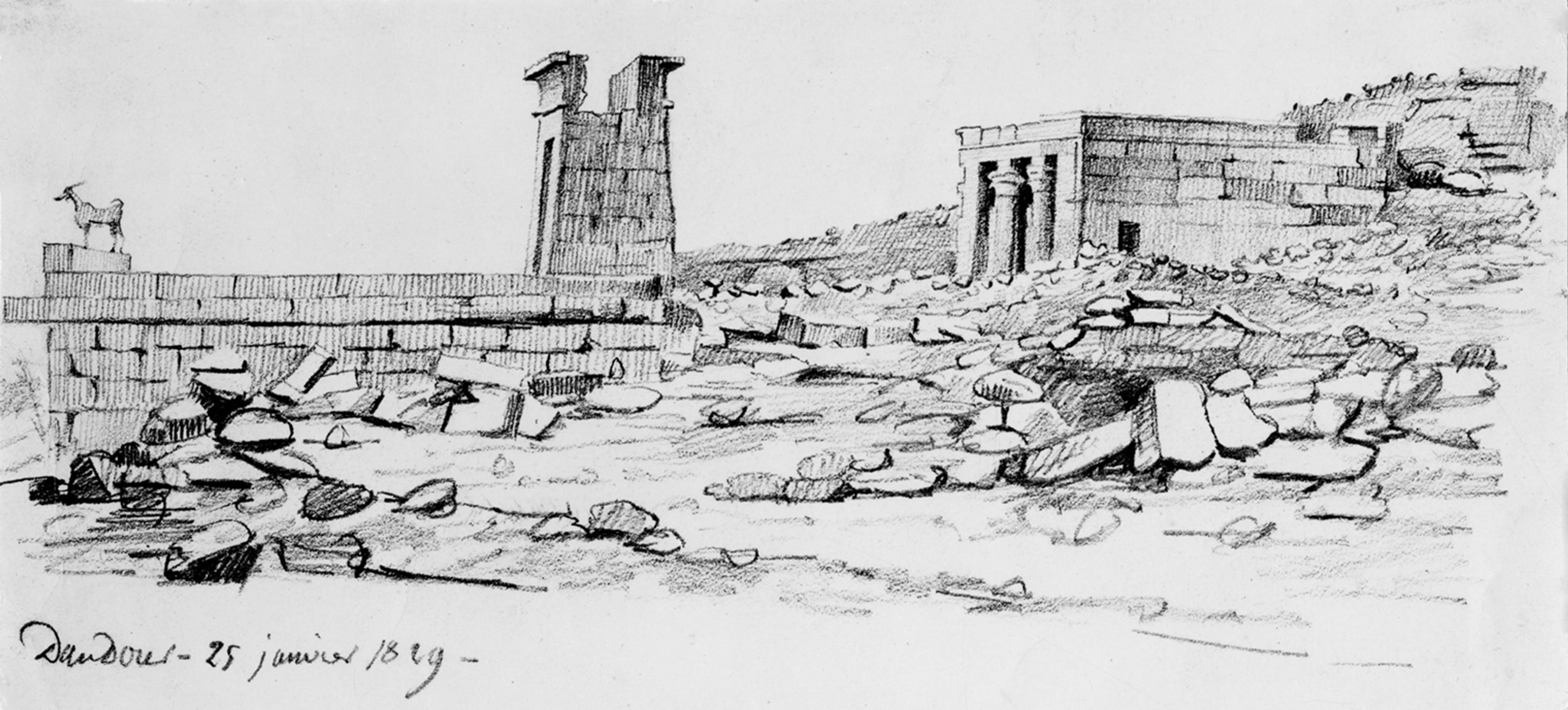

Nestor L'Hôte (French, 1804–1842)

Nestor L'Hôte, Dendur—25 January 1829—, reproduced in Sur le Nil avec Champollion (Orléans-Caen: Editions Paradigme, 1993), 218–19.

Having studied drawing and painting in secondary school, Nestor L'Hôte had the good fortune to be one of four young artists that accompanied the noted French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion on his 1828–30 expedition to Egypt. Arriving in Alexandria in August, the members of the expedition eventually sailed as far south as the second cataract near Wadi Halfa in Sudan. On the return voyage, they stopped at Dendur, reaching the temple just before sunset on January 25, 1829. L'Hôte's journal entry for the day describes the soundscape:[3]

After supper, we amused ourselves with an echo which is, I think, one of the most remarkable that exists: leaving the left bank [of the river], the sound is repeated several times in the hills of the right bank, at long intervals and with increasing intensity. It repeats with admirable clarity the twelve syllables of an Alexandrine verse, and replies to gunshots with frightful claps of thunder.

L'Hôte and his companions regretted that such an effect could not be expressed in painting.

L'Hôte's pencil sketch of the temple is dated January 25, but the light appears to be coming from the east, suggesting that it was completed the next morning. The simple sketch gives an excellent impression of the temple in its setting, with the scale indicated by a goat standing on the parapet. The angle, looking southwest, seems to have been chosen to allow the artist to include the chamber cut into the hillside behind the temple, which is indicated by a dark shadow.

David Roberts (British, 1796–1864)

David Roberts, Temple of Dendur, Nubia, in Egypt & Nubia, vol. 2 (London: F.G. Moon, 1846–49), plate 20.

In 1838, David Roberts set out on a voyage to Egypt and the Holy Land. He intended to make drawings that he could later use to create and sell paintings and lithographs to a public increasingly interested in the Near East and, in particular, in the monuments of ancient Egypt.

Arriving in Alexandria on September 24, Roberts passed the first cataract above Aswan on November 1 and arrived on November 4 at Dendur, which he found insignificant after the temples he had seen along the way.[4] In the watercolor painting and lithographs that he later made based on these drawings, Roberts exaggerated the break along the right edge of the facade, and drew the human figures at a height that makes the temple appear to be twice its actual size.

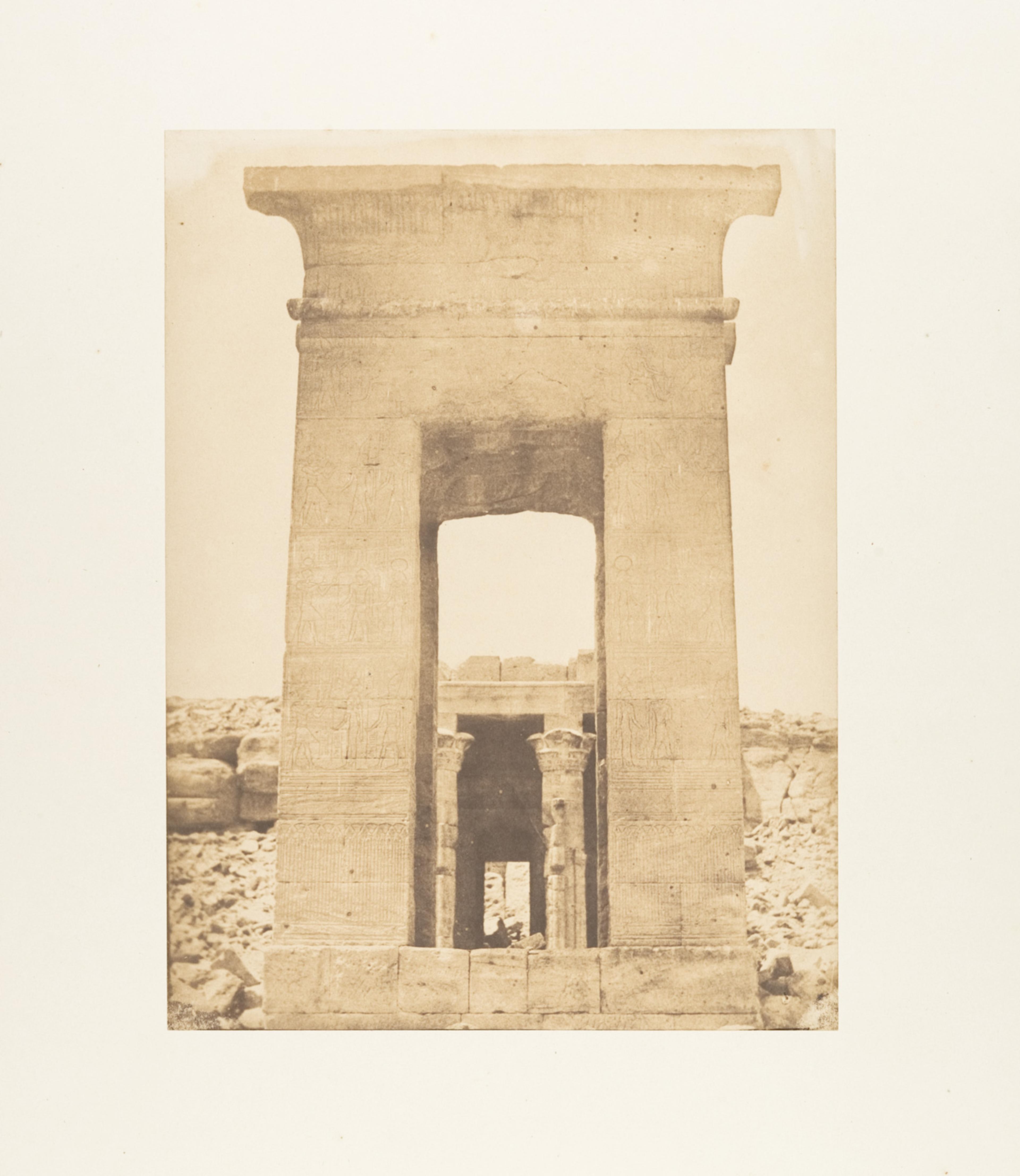

Maxime Du Camp (French, 1822–1894)

Maxime du Camp (French, 1822–1894). View of the Propylon of the Temple of Dendur (Tropic of Cancer), April, 1850. Salted paper print from paper negative, Image: 8 7/8 x 6 5/8 in. (22.5 x 16.8 cm), Mount: 18 3/4 x 12 1/2 in. (47.5 x 31.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005 (2005.100.376.131)

In 1849, Maxime du Camp and his friend Gustav Flaubert set out on a voyage to Egypt and the Near East. In preparation for the trip, Du Camp had taken some lessons in photography, intending to make a record of their travels. They arrived at Alexandria in mid-November and proceeded up the Nile as far as Abu Simbel. On the return trip, they reached Dendur in the evening of April 6, 1850, just in time to see the temple silhouetted against the sky and hear frogs croaking on the banks of the river.[5]

Du Camp was not impressed by what he considered the inferior quality of the reliefs on the temple's gateway, but he took a photograph of its eastern face, looking through to the temple beyond. The unusual perspective was possible because the pavement of the terrace in front of the gateway was partially destroyed at the time, which allowed Du Camp to set up his camera at eye level with the gateway's threshold.

A view of the south side of the main Temple building was also included in the 1852 publication of Du Camp's travels.[6]

Félix Teynard (French, 1817–1892)

Félix Teynard (French, 1817–1892). Dandoûr, Nubie, 1851. Salted paper print from paper negative, image: 9 1/2 x 12 1/4 in. (23.9 x 31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds from various donors, 2013 (2013.431)

The first photograph showing a complete view of Dendur was taken by Félix Teynard, a French civil engineer who traveled to Egypt in 1851 with the express purpose of supplementing the great Napoleonic work Le déscription de l'Egypte with a photographic record of the ancient monuments.[7] The documentation of the Déscription ended at Aswan, and Teynard used the work of Franz Christian Gau as his guide to the temples of Nubia. Teynard was probably standing close to the river bank when he took this photograph. The view, looking southwest, shows the curved front of the temple's platform, and gives a sense of its elevation above the Nile, which was at its lowest level of the year. The rock-cut shrine behind the temple is also visible.

Amelia B. Edwards (British, 1831–1892)

Writer Amelia B. Edwards, who became a major patron of British Egyptology, made her first trip to Egypt in the winter of 1873–74. Arriving in Alexandria at the end of November, she traveled south to the second cataract and stopped at Dendur on the return voyage, sometime at the end of February. She visited the temple at sunset, describing it as an "exquisite toy." Upon returning to England, she documented her journey in A Thousand Miles up the Nile, which was illustrated with woodcuts based on her drawings.[8]

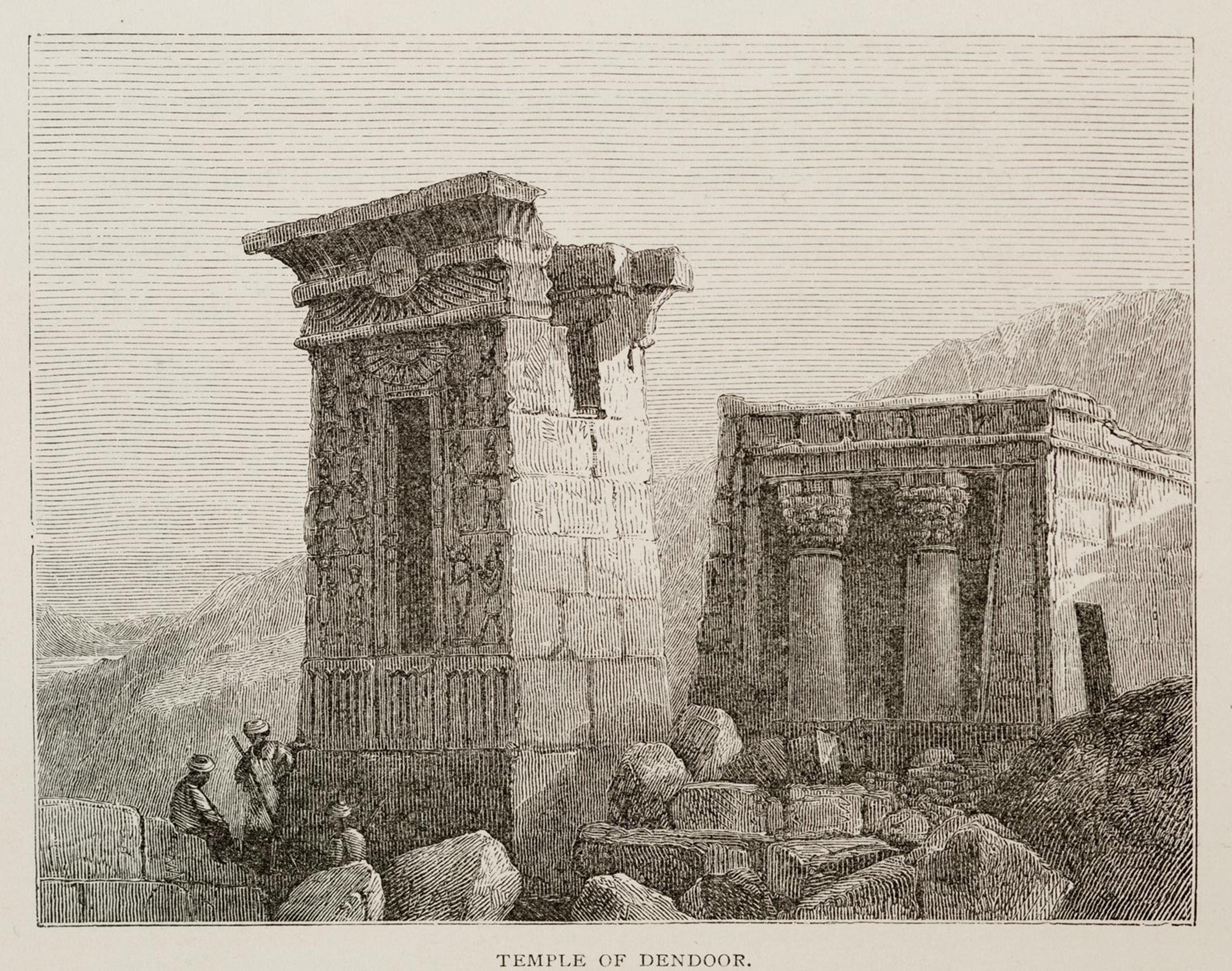

Temple of Dendoor, wood engraving by G. Pearson after an original drawing by the author, in Amelia B. Edwards, A Thousand Miles up the Nile (New York, 1877), 548.

Edwards's illustration of the temple is recognizable, but the proportions are distorted, making it look bulkier than in reality and more like the "toy" she describes in her text. It's difficult to understand where the figures in front of the gateway are supposed to be loitering, and it's quite possible that she finished this part of the drawing from memory. It appears from her text that they spent very little time at Dendur, continuing down the river that night to Kalabsha.

Frederick Arthur Bridgman (American, 1847–1928)

Frederick Arthur Bridgman (American, 1847–1928). The Temple of Dendur, Showing the Pylon and Terrace, 1874. Watercolor and gouache on off-white wove paper, 4 7/8 x 7 5/8 in. (12.4 x 19.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 2000 (2000.597)

Having started out at the age of sixteen as an engraver for the Department of the Treasury, Frederick Arthur Bridgman went on to study art at the National Academy of Design in New York and moved to Paris in 1866 to further his studies. In 1872 he made a trip to North Africa, visiting Egypt during the winter of 1873–74. During his voyage up the Nile, he made dozens of sketches of the landscape, ancient monuments, and contemporary architecture, which he later incorporated into his Orientalist paintings. Bridgman painted three watercolor and graphite views of Dendur on February 21, 1874, that are now in the Museum's collection. One watercolor shows the temple at midday, with the artist looking northwest. Bridgman has included a squatting man holding a spear for both atmosphere and scale.

And There Is More . . .

The Temple of Dendur is represented by several other works of art in The Met collection, including a watercolor by Roberts; two watercolor and graphite paintings of the temple by Bridgman (2000.598, 2000.599); a drawing of Nubians in front of The Temple of Dendur by John Singer Sargent; and a photograph of the temple by Félix Bonfils.

Footnotes

[1] France. Commission des sciences et arts d'Egypte, Description de l'Egypte, ou, Recueil de observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Egypte pendant l'éxpédition de l'armée française. Publié par les ordres de Sa Majesté l'empereur Napoléon le Grand. 21 vols. (Paris, Imprimerie impériale, 1809–1828).

[2] Franz Christian Gau, Antiquités de la Nubie: ou, Monumens inédits des bords du Nil, situés entre la première et la seconde cataracte, dessinés et mesurés en 1819 (Stuttgart, 1822), plates 23–26.

[3] Nestor L'Hôte, Sur le Nil avec Champollion: lettres, journaux et dessins inédits de Nestor L’Hôte: premier voyage en Egypte, 1828–1830 (Orléans-Caen: Editions Paradigme, 1993), 218.

[4] James Ballantine, The Life of David Roberts, R.A., compiled from his journals and other sources; with etchings and facsimiles of pen-and-ink sketches by the artist (Edinburgh, 1866), 94.

[5] Maxime du Camp, Le Nil: Egypte et Nubie, avec une carte spéciale, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1860), 159; and Francis Steegmuller, ed. and trans., Flaubert in Egypt: A Sensibility on Tour. A narrative drawn from Gustave Flaubert's travel notes and letters (Chicago: Academy Chicago Limited, 1979), 147.

[6] Maxime du Camp, Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie: dessins photographique recueillis pendant les années 1849, 1850, et 1851 accompagnés d'un texte explicatif et précédés d'un introduction (Paris, 1852), plate 93. A print of this photograph (2005.100.376.132) is also among The Met's holdings.

[7] Félix Teynard, Egypte et Nubie, sites et monuments les plus intéressants pour l'étude de l'art et de l'histoire: atlas photographie accompagne de plans et d'une table explicative servant de complement a la grande description de l'Egypte, 2 vols. (Paris and London, 1858), plate 121. For the Napoleonic documentation, see above, n. 1.

[8] Amelia B. Edwards, A Thousand Miles up the Nile, with illustrations engraved on wood by G. Pearson after finished drawings executed on the spot by the author (New York, 1877).