The region of Nubia begins at the point just south of Khartoum in the Sudan where the Blue and White Nile join, and is linked to Egypt by the Nile River, which flows northward through both lands to the Mediterranean. Riverine navigation in Nubia was impeded by a series of six narrow, rocky passages called cataracts, areas where granite outcrops emerge from beneath the softer sandstone that underlays most of the Nile Valley (fig. 1). The First Cataract, just south of Aswan in Egypt, marks the separation of Egypt and Nubia, while the Second Cataract separates Upper (southern) and Lower (northern) Nubia. Fertile land was not continuous along the roughly 160 miles of the Nubian Nile; rather, cultivated areas beside the river were interspersed with desert sands and rocky mountains.

Over the millennia a series of cultures and kingdoms rose and fell in Nubia, but the Nubian people did not have a written language of their own until the Meroitic Period (ca. 275 B.C.–300 A.D.). As a result, our knowledge of their history and culture derives either from Egyptian sources, which are often biased against other societies, or archaeological excavations. While some scientific exploration of Nubia took place in the early to mid-nineteenth century, extensive work began only in the early twentieth century, when a dam was first constructed at Aswan.

Map of Egypt and Nubia by Sara Chen

Key to our understanding of the region is the work of the Archaeological Survey of Nubia, which began in September 1907. Also adding immeasurably to our knowledge of Nubia was the Nubian Salvage Project carried out at the behest of the Egyptian government between 1960 and 1964, when plans to build the High Dam at Aswan threatened to submerge the monuments of Lower Nubia, including the Temple of Dendur. This UNESCO-sponsored initiative involved more than seventy separate archaeological missions from twenty-five different countries.

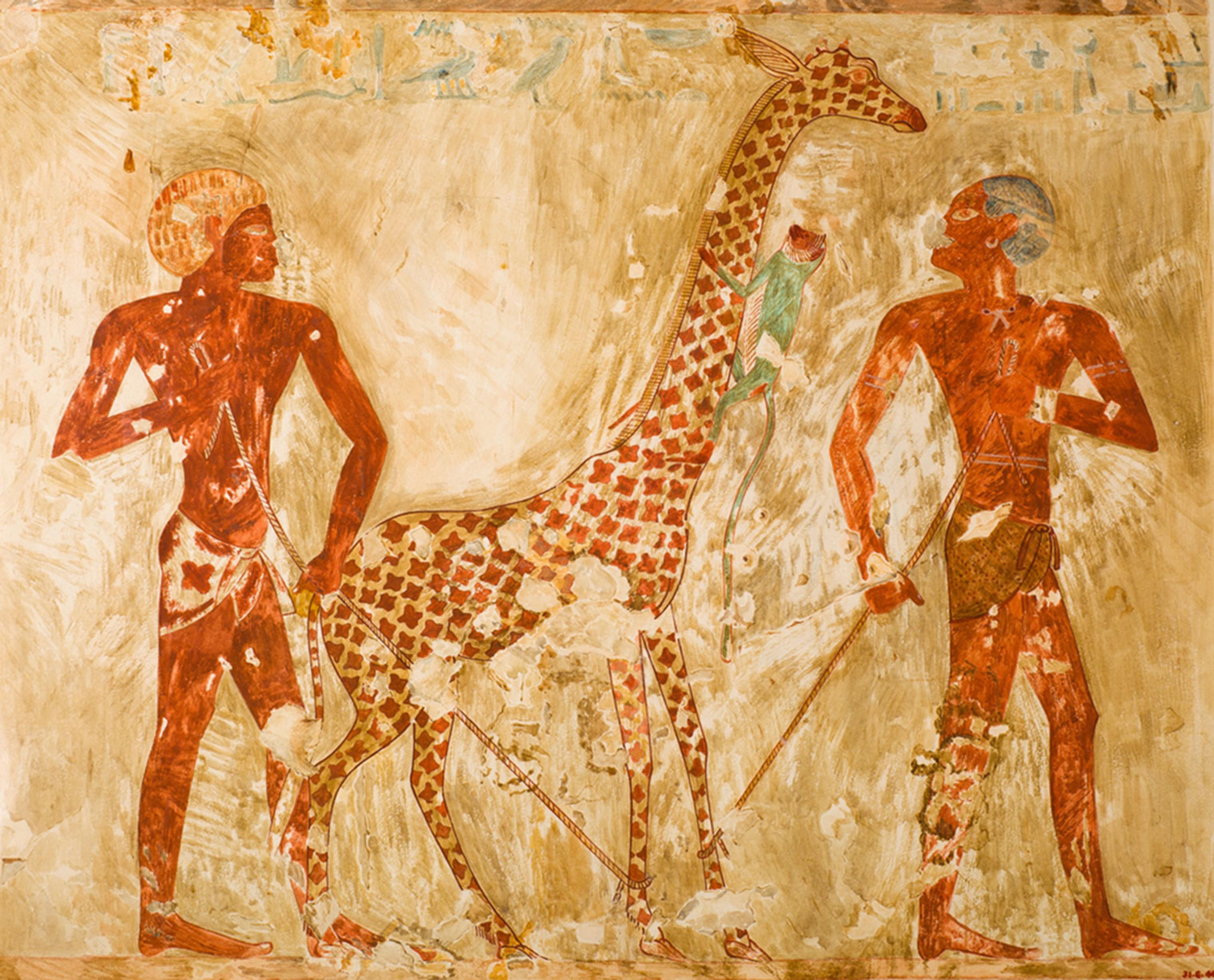

Ancient Nubia had a complex series of political interactions and cultural exchanges with Egypt, largely based on its position as an intermediary between the Mediterranean world and sub-Saharan Africa, which made it a key transit point for luxury goods such as ivory and exotic objects (fig. 2). Of great importance was gold, a commodity found in the Nubian deserts and greatly prized by the Egyptians. Relations of trade and warfare are known as early as the beginning of the Dynastic Period in Egypt (ca. 3100 B.C.) and continued throughout the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2100 B.C.).

Facsimile painting depicting Nubians with a giraffe and a monkey. Original: New Kingdom, Dynasty 18 (ca. 1504–1425 B.C). Original: From Thebes, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, tomb of Rekhmire (TT 100). Facsimile by Nina de Garis Davies (1881–1965). Tempera on paper, 18 3/4 x 23 1/8 in. (47.5 x 58.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1931 (31.6.40)

During the Middle Kingdom, and particularly in the Twelfth Dynasty (ca. 1981–1802 B.C.), the Egyptians built fortresses in the region of the Second Cataract in order to secure access to this gold, as well as to defend against the rising Kingdom of Kush farther to the south. However, Nubians also lived in Egypt as respected members of society (fig. 3), and Nubian archers at times served as mercenaries in the Egyptian army. The text of an imposing boundary stela erected by the Pharaoh Senwosret III (1878–1840 B.C.) brags that this ruler had set the boundary of Egypt further south than his fathers while utterly humiliating the defeated Nubians.

Figure of a woman of Nubian descent who may have served as an attendant to a royal woman or Hathor priestess. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11 (ca. 2030–1981 B.C.). From Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, tomb MMA 511. Wood, paint, 7 1/8 x 1 3/4 x 1 1/4 in. (18 x 4.5 x 3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1926 (26.3.231)

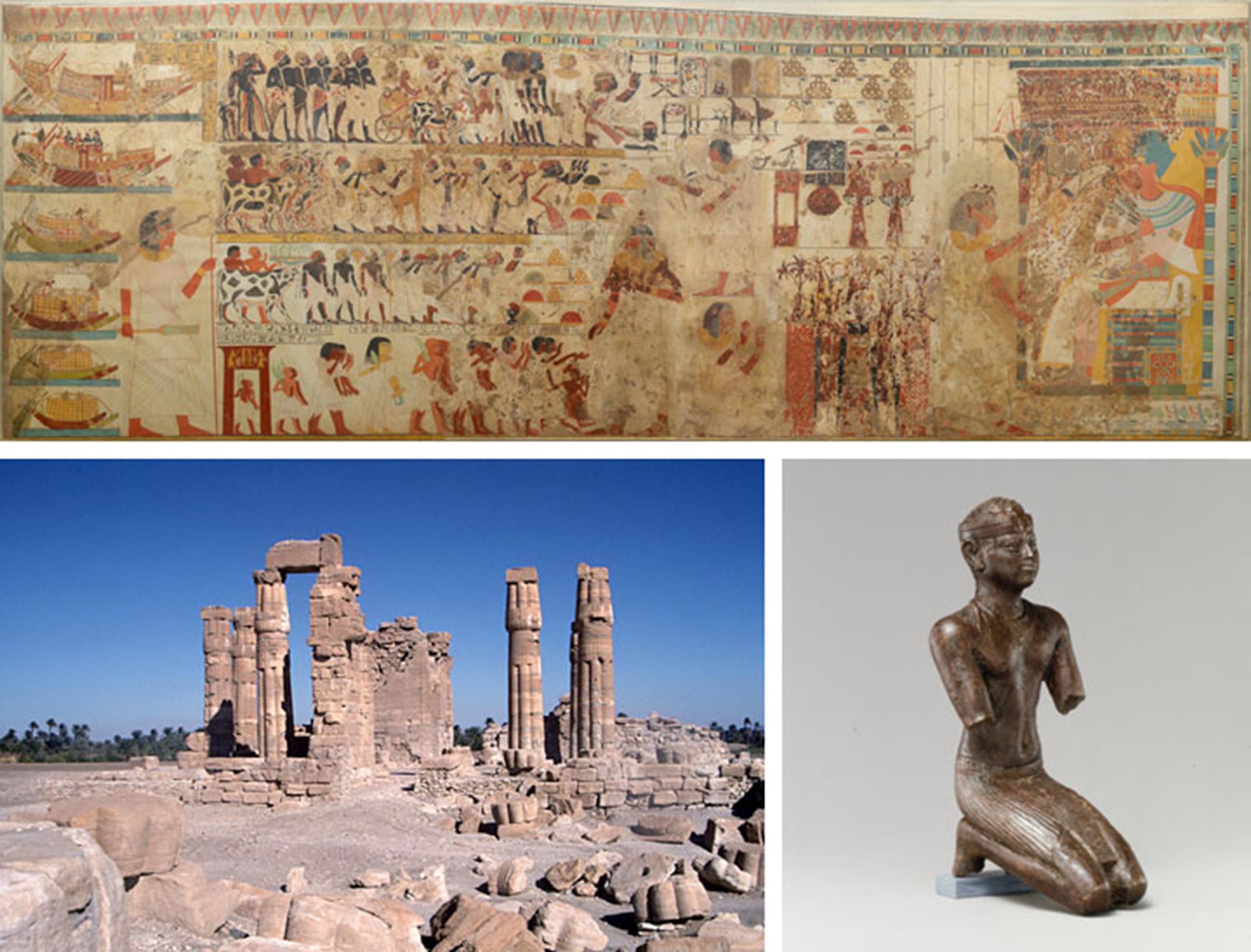

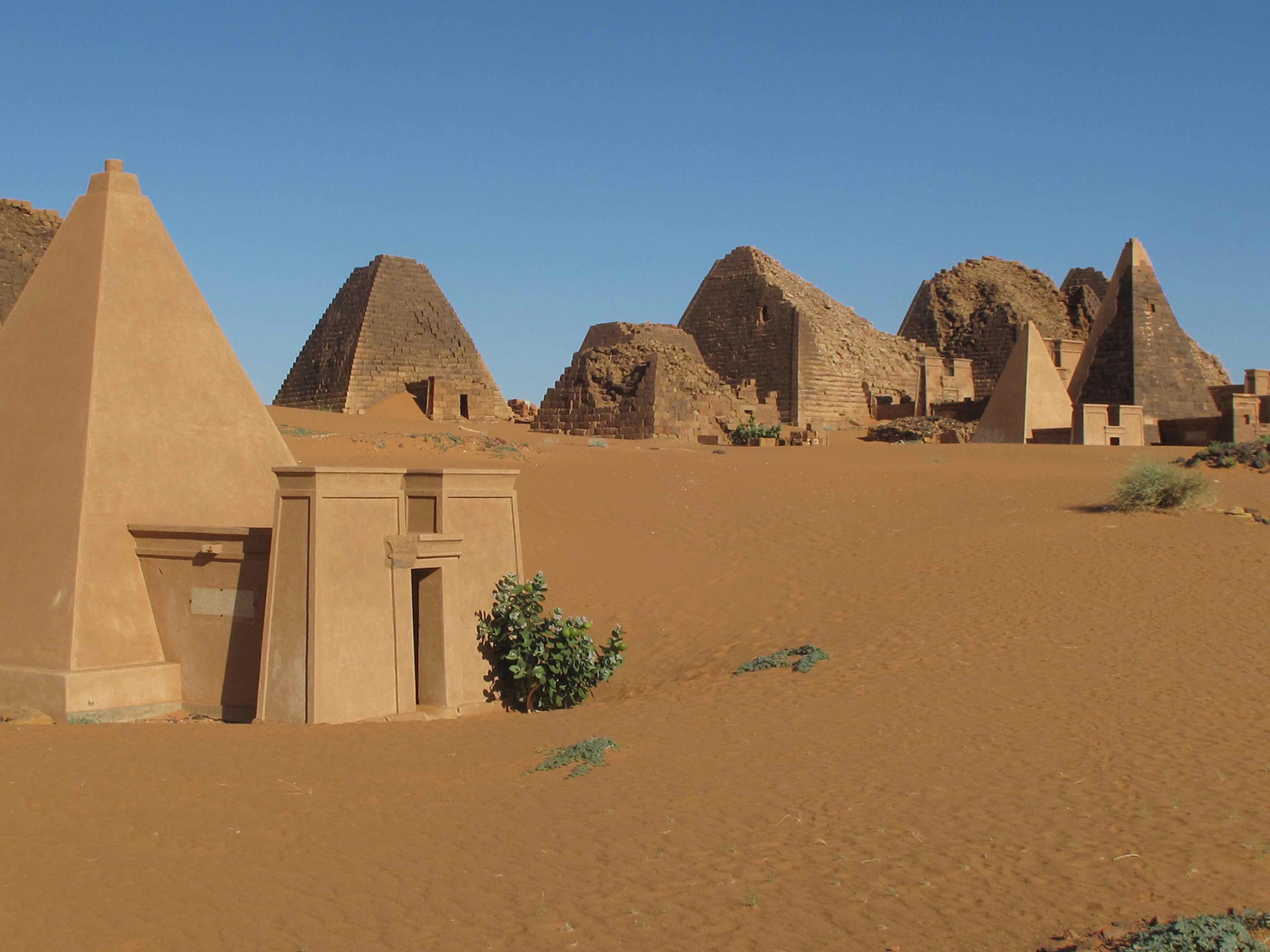

Egypt conquered all of Nubia during the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.), installing viceroys who administered the lands and collected tribute (fig. 4). New Kingdom pharaohs commissioned an impressive group of temples in a variety of locations. Many of these were dedicated to Amun, one of the most important Egyptian deities, as well as to gods and goddesses of the Nubian pantheon. The tables were turned in the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (ca. 773–664 B.C.) when Kushite kings conquered all of Egypt, ruling largely from the traditional Egyptian capital of Memphis, south of modern Cairo, but returning to Nubia for burial in pyramid-shaped tombs.

Top: Facsimile painting depicting Nubian tribute presented to a king. Original New Kingdom, Dynasty 18 (ca. 1353–1327 B.C.). From Thebes, tomb of Huy. Facsimile by Charles K. Wilkinson, ca. 1923–27. Tempera on paper, 71 5/8 x 206 3/8in. (182 x 524 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1930 (30.4.21). Bottom left: The temple of Soleb built by Amenhotep III (ca. 1390–1352 B.C.) in Upper Nubia. Photo by Artur Brack. Bottom right: Figure of a kneeling Kushite pharaoh. Late Period, Dynasty 25 (ca. 713–664 B.C.). From Egypt and Sudan, Nubia. Bronze, precious-metal leaf, 3 x 1 1/4 x 1 3/8 in.(7.6 x 3.2 x 3.6 cm).The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift and Anne and John V. Hansen Egyptian Purchase Fund, 2002 (2002.8)

After the Romans conquered Egypt in 30 B.C., it became the personal estate of the Emperor Augustus and was ruled by the prefect Petronius. Egypt provided significant revenues to Rome, primarily in the form of agricultural commodities, but Egypt also exported papyrus, luxury goods, and raw materials such as semiprecious stones and gold from the desert. Lower Nubia at that time was controlled by the Meroitic kingdom, a continuation of the Kushite house that had been pushed south by the Egyptians to a new capital between the Fifth and Sixth Cataracts. The area was attractive to the Romans as it provided access to trade routes and gold, and not long after they occupied Egypt, Rome moved south to annex it.

In 24 B.C., the Meroitic rulers sent a military expedition north to protect their interests, apparently reaching Thebes, but Petronius retaliated by marching south to the Meroitic seat at Napata. There, the Romans defeated the ruling queen mother (kandake) Amanirenas and sacked the Meroitic capital (fig. 7). After a series of battles, the two sides signed the Treaty of Samos in 20 B.C., which gave Rome and Augustus control of the Dodecaschoenus—an administrative district that stretched from Philae Island, at the First Cataract, to Hiera Sycaminos (modern Maharraqa) 75 miles to the south—while Meroe maintained its authority over the rest of Nubia. The successful conclusion of the treaty, which also designated the Dodecaschoenus as a neutral buffer zone where both Romans and Nubians were allowed free access to temple precincts, likely ushered in a 300-year period of peace.

Pyramids at Meroe. Photo courtesy of Peter Lacovara

The cult of the goddess Isis, which had spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean, increased in importance in the Nile Valley during the Hellenistic and Roman eras. The area of the Dodecaschoenus, considered the personal estate of Isis herself, was a key pilgrimage area for Nubia. The Temple of Dendur, dedicated to Isis; her husband/brother, Osiris; and Pedesi and Pihor, two deified Nubians who may have been sons of a local ruler, was one of a series of small temples built by Petronius on behalf of Augustus in this area. Dendur became part of a ritual landscape centered on Philae Island (fig. 8), where the main Isis temple stood, and the Abaton on Bigeh Island, one of the sixteen sites said to contain the tomb of Osiris. As such, it was an essential part of the Roman strategy to use religion to help mediate its complex social and political relationship with Nubia.

The kiosk on Philae Island probably built by the Emperor Augustus (30–14 B.C.). Photo by Adela Oppenheim