Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in "Water Moon" Form (Shuiyue Guanyin), 11th century. China. Liao dynasty (907–1125). Wood (willow) with traces of pigment; multiple-woodblock construction, 46 1/2 x 37 1/2 x 28 in. ( 118.1 x 95.3 x 71.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1928 (28.56)

The Metropolitan's collection of Chinese religious sculpture is the largest outside of Asia. The availability of new scholarly information and analytical techniques, as well as recent archaeology in China, prompted the Museum to undertake an in-depth study of the collection for the 2010 publication Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Yale University Press) that I co-wrote with Denise Patry Leidy, curator in the Department of Asian Art. This study revealed new information about the objects, in some cases resulting in the re-dating of a sculpture and, in others, in the reassignment of a sculpture's provenance (place of origin).

Investigation of the larger-than-lifesize polychrome (painted) wood sculpture Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in "Water Moon" Form (Shuiyue Guanyin) demonstrates the value of combining technical analysis with art historical research. When the sculpture arrived in the conservation laboratory it was considered by art historians to have been made in southern China in the eleventh century, during the Song dynasty (960–1279).

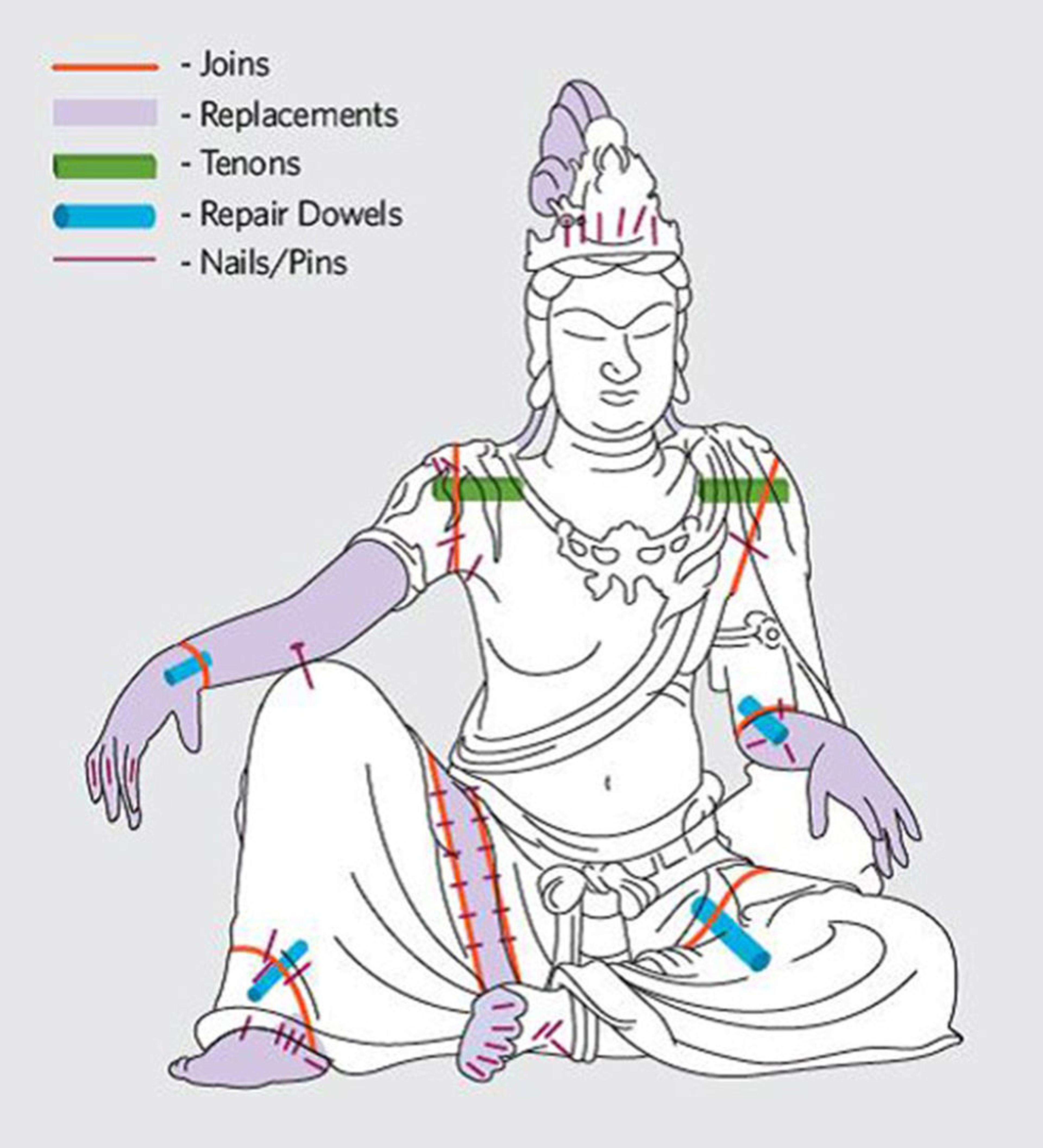

Our initial step was to X-radiograph the sculpture to determine how it was constructed and if there were any restored areas. Radiography also ensured that any wood samples taken for further analysis were removed from an original block and not a later replacement. A detailed line drawing based on the X-radiographs indicates the location and method of joins, as well as a number of restorations.

This line drawing illustrates the location of joins, dowels, pins, nails, repairs, and replacement parts.

As reflected in the drawing, our X-radiographic study revealed that the head and torso of the sculpture were carved from one large central block of wood, while a second large block was used for the legs. The top of the head was made of an additional smaller block; the topknot was replaced. Both of the arms from above the elbows down to the fingertips are also replacements, as are the toes on both feet. The join between the two main blocks has been repaired several times.

To date the sculpture, a piece of wood the size of a matchstick was taken from the underside of the main torso block and sent to a specialist laboratory for Carbon-14 dating. The Carbon-14 results for the sculpture were consistent with the proposed eleventh-century origin.

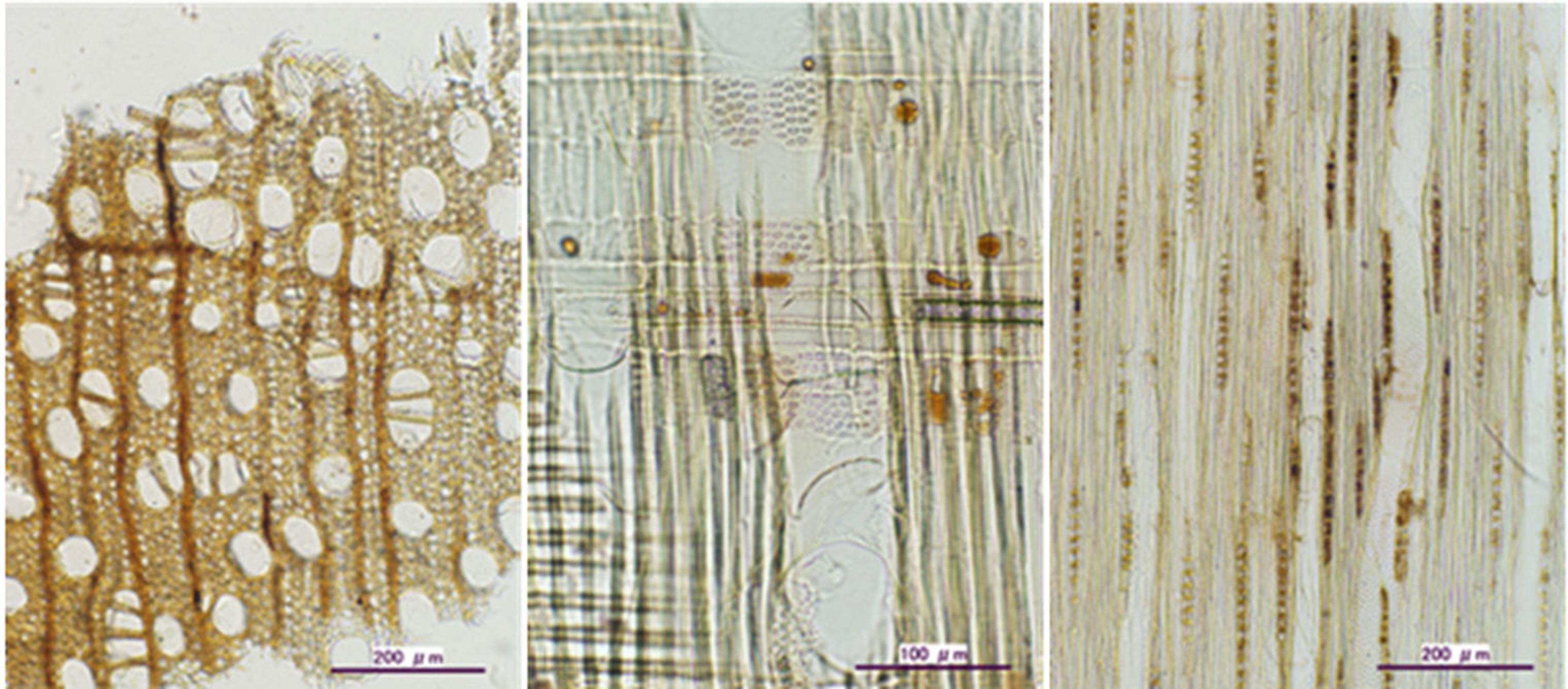

At the same time, another small sample from the torso was sent to wood experts in Japan to identify the type of wood. We learned that the sculpture was carved from willow (Salix sp.), a species that grows in northern and central China, which was not consistent with the original hypothesis that the sculpture came from the south. Knowing both the date and type of wood, combined with an understanding of the sculpture's style, allowed us to determine that although the sculpture had been dated correctly to the eleventh century, its provenance had been incorrect. In fact, it had most likely been created in the area ruled by the Liao dynasty (907–1125), one of the foreign dynasties controlling northern China at the time.

Photomicrographs of a single small wood sample from the sculpture's torso. The small size of the sample can be seen by the scale measuring in microns (one micron is one millionth of a meter). The sample was cut into three thin sections to expose the different directions of the wood grain (tangential, radial, and longitudinal), which is necessary to identify the wood. Photograph courtesy Mectilid and Itoh

More surprising than the sculpture's provenance was the discovery, via X-radiography, of two inner consecratory chambers that were most likely used for ritual deposits. Placing precious materials in Asian objects—either actual relics or symbolic items—began about the first century A.D. Actual relics included what were believed to be fragmentary parts of the Buddha or of a monk's body—such as a tooth, hair, bone, ashes, or nail clippings—that, when placed inside a sculpture, invested it with the presence and power of the holy being. Symbolic ritual deposits—made of shiny, possibly precious materials such as mother-of-pearl, rock crystal, lapis lazuli, silk, wood, or sutras (sacred texts written on paper or textile)—also served to sanctify a sculpture.

In the context of this wood sculpture, the material of the consecratory deposits determines whether they can be revealed in an X-radiograph. Organic materials such as paper or textiles may not be visible, whereas inorganic materials such as metal or stone would be seen. X-radiographs of the bodhisattva revealed two chambers, one located in the head and the other in the torso.

X-radiograph of the side view of the head revealing a hollowed-out chamber; the area is less dense and therefore appears darker in the image. The nails that are visible were meant to hold the smaller blocks of wood to the head and parts of the crown, which are now missing.

Our current research includes noninvasive investigation to determine if relics remain inside the head chamber. The torso chamber, which had been opened prior to the sculpture's arrival at the Museum, is empty. Circular depressions on the interior of the chamber door conform to the exterior profile typical of Chinese mirrors, suggesting the door may have held a bronze mirror whose reflective side would have faced into the body cavity. Very few sculptures from this time period exist and even fewer have been studied, so it is difficult to say whether this feature is unique. Mirrors have long played an important role in Chinese culture and in many contexts have been believed to be amuletic and protective. Only one other wood sculpture in the Museum's collection of Chinese art (34.15.1) contains a similar depression with a small mirror in its chamber door.

Looking inside the sculpture's torso from the bottom, with the sculpture lying on its back. The door to the back consecratory chamber features circular depressions for a mirror.

The use of advanced technological resources to re-examine works of art in the Museum's collections allows us to gain a greater understanding of the objects under our care. More information on our recent findings about Chinese religious sculpture is available in Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.