Background

Works of art are generally composed of heterogeneous materials consisting of inorganic and/or organic compounds structured in complex ways. In traditional oil paintings, the components are typically inorganic and/or organic pigments mixed with a drying oil binder, usually applied in multiple layers over a support, such as canvas, wood, or metal, with protective organic coatings on top. Deterioration processes often involve interactions at the interfaces of these components, with degradations in one triggering subsequent chemical reactions and physical changes in another.

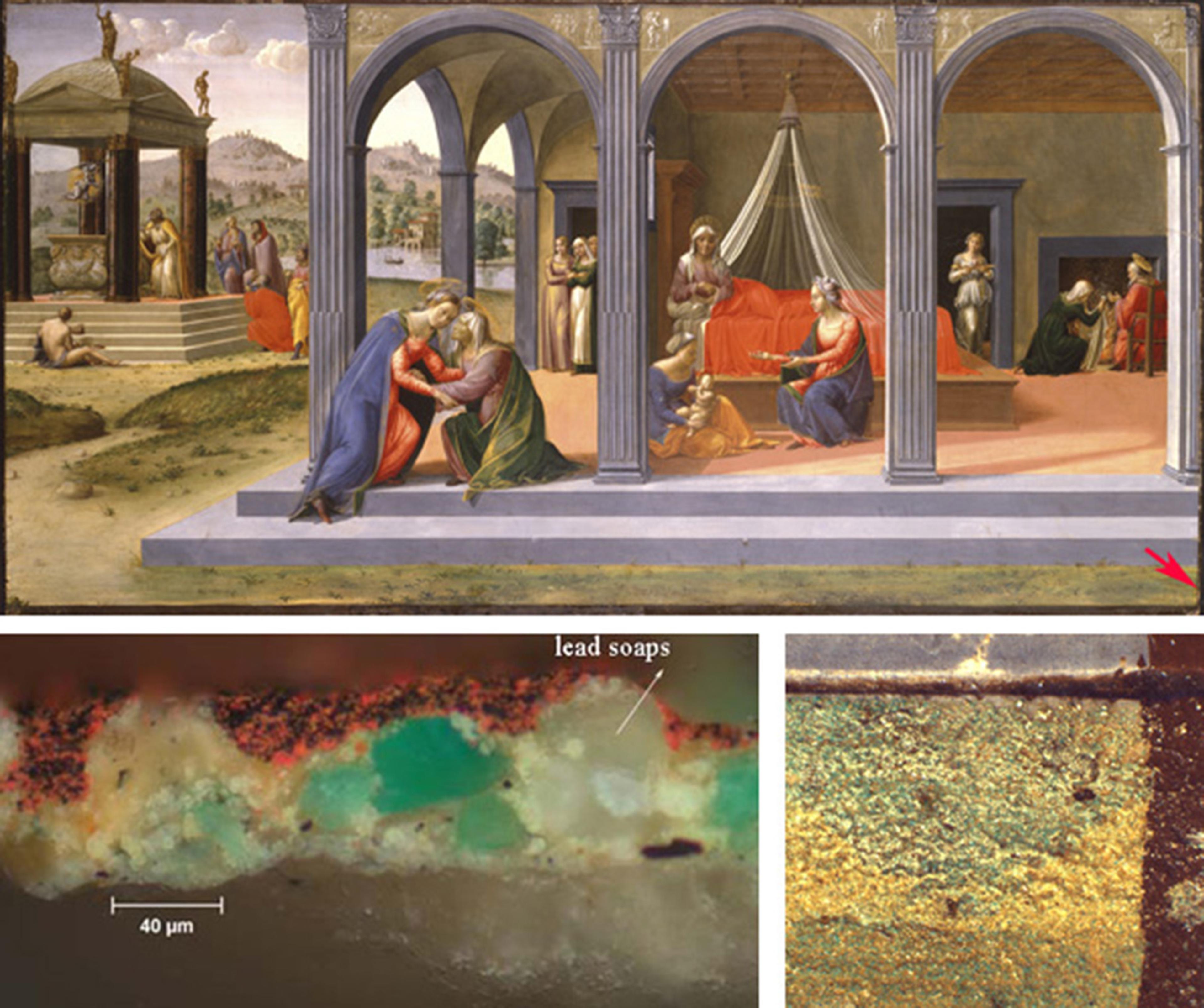

In 1997, during research associated with the conservation of Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp [1–4] in the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, aggregates were observed in the lead-containing ground preparation of the painting, which puzzled conservators and lead to an in-depth analytical investigation. Microscopic analysis of paint cross-section samples removed from this painting revealed that the aggregates contained lead soaps. Soaps are salts, also called carboxylates, of lead and long chain fatty acids (lead palmitate and lead stearate). Since the initial revelation, lead and other heavy metal soaps have been detected and reported to be the cause of deterioration in hundreds of oil paintings dating from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries.[2, 3, 5–8] One example in The Met collection is Francesco Granacci’s The Birth of Saint John the Baptist (ca. 1506–1507). The granular texture observed in the grass paint passage at the lower right corner of the painting was identified to be caused by lead soap formation. In this figure, a microscopic sample removed from the grass area and mounted as a cross-section shows lead soap aggregates protruding through the paint surface.

Francesco Granacci (Italian, 1469–1543). Scenes from the Life of Saint John the Baptist, ca. 1506–7. Tempera, oil, and gold on wood, 30 9/16 x 59 1/2 in. (77.6 x 151.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Gwynne Andrews, Harris Brisbane Dick, Dodge, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds, funds from various donors, Ella Morris de Peyster Gift, Mrs. Donald Oenslager Gift, and Gifts in memory of Robert Lehman, 1970 (1970.134.1). The cross-section of a paint sample removed from the grass area, in lower right border, was found to contain lead soaps protruding through the paint surface that give rise to the granular to surface texture of the paint

Soap formation

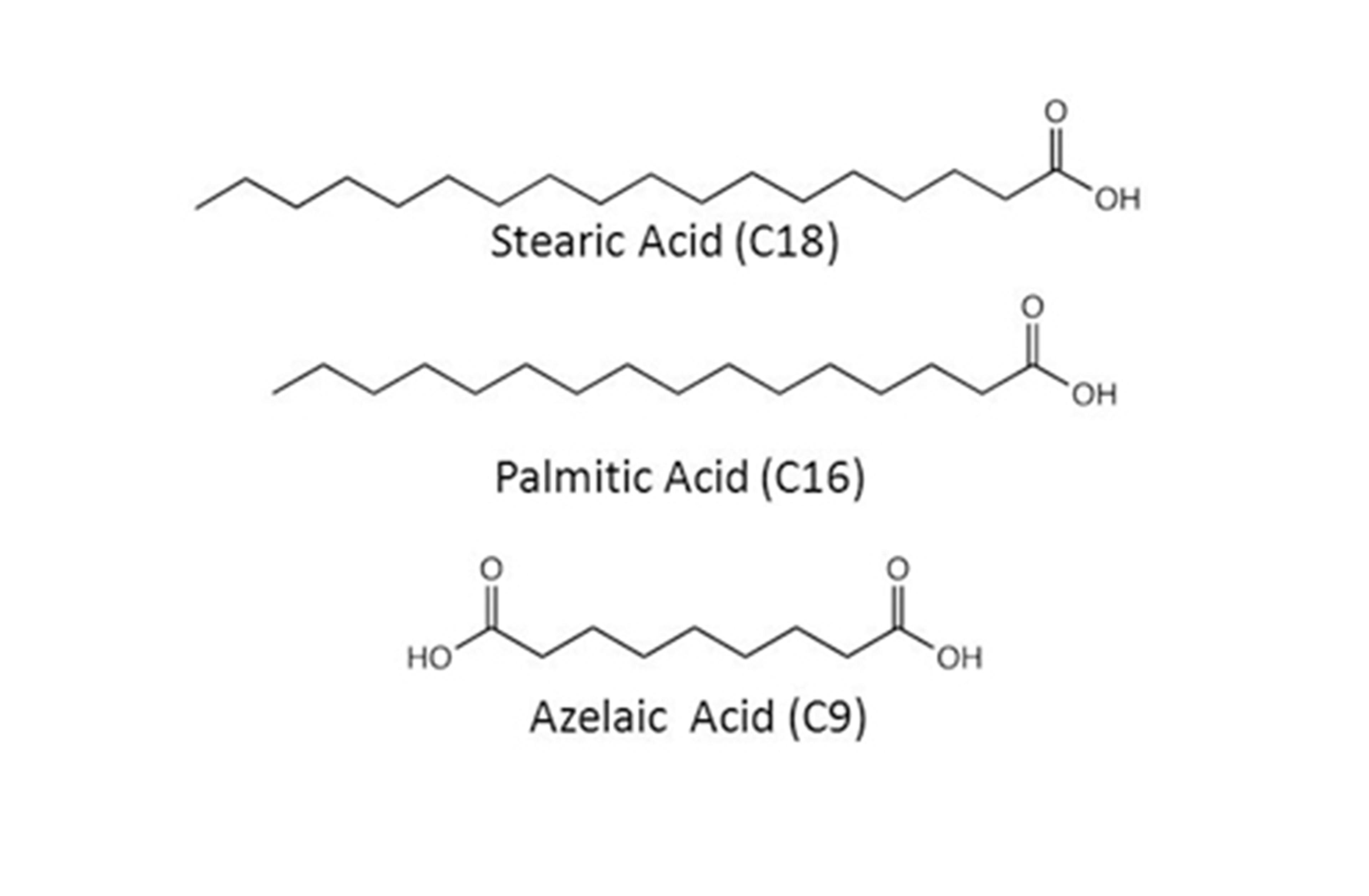

Soaps form when heavy metal-containing pigments, such as the commonly used lead white and lead-tin yellow type I, react with fatty acids that result from the hydrolysis of glycerides in the oil binding medium, or from protective coatings.[1–3, 6, 9] Soap inclusions in oil paintings, from a broad range of geographical locations and dates, studied by gas-chromatography-mass-spectrometry (GC-MS) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), have been reported to contain lead carboxylates of the stable saturated C16 (palmitic) and C18 (stearic) straight-chain monocarboxylic fatty acids, and relatively small amounts of—in some cases none—lead azelate (C9).[2, 6] Azelaic acid results from the degradation of polyunsaturated C18 fatty acids in the oil matrix, and it is usually found in significant amounts in old paint films[10]. The free fatty acids known to be involved in soap formation are shown below.

Structure of stearic, palmitic, and azelaic acids. These fatty acids result from the hydrolysis of glycerides in the oil binding medium and react with heavy metal–containing pigments to form heavy metal soaps

Heavy metal carboxylates can form from sources of heavy metals other than pigments—for example, when a lead-containing compound is added to a paint formulation as a drying agent. Soap formation is not restricted to oil paintings, long chain fatty acid carboxylates of copper and zinc have been found to be present on the surfaces of metallic cultural artifacts, as a result of treatments or contact with organic substances such as animal fats, oils, or leather.[11]

Conservation issues

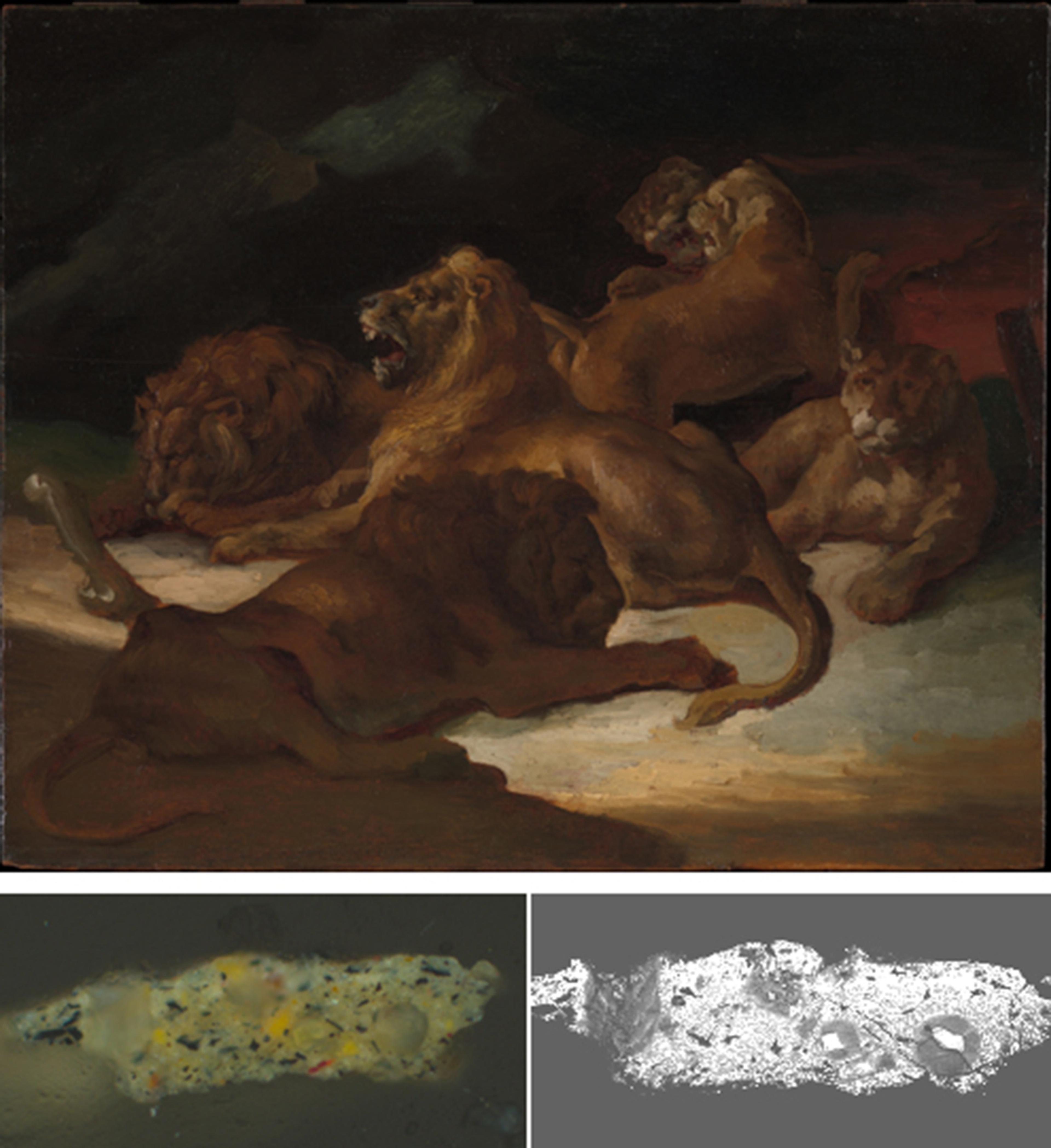

The process of soap formation may compromise the integrity of an artwork in different ways. Soap aggregates can be as large as 100–200 μm in diameter and may break through the paint surface[2, 3, 5–8], such as in the case of The Birth of Saint John the Baptist, as discussed above. In Théodore Gericault’s Lions in a Mountainous Landscape (ca. 1818–20), almost transparent lead soap–containing aggregates can be observed in a sample removed from the right edge of the painting and, inside these aggregates, unreacted lead white pigment particles are still visible. But soaps may also migrate to the surface of the painting and remineralize to form crusts of lead carbonates, hydroxychlorides, sulfates, and oxalates, presumably by reacting with carbon dioxide and other compounds in the environment.[1,2,6,9,12]

Théodore Gericault (French, 1791–1824). Lions in a Mountainous Landscape, ca. 1818-20. Oil on wood, 19 x 23 1/2 in. (48.3 x 59.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Nineteenth-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Funds and Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2011 (2011.5). The bottom left is a photomicrograph taken with visible illumination of a cross-section removed from the right edge of the painting, where soaps appear as round, almost transparent inclusions in the paint film. The bottom right is an image of the same sample acquired with a scanning electron microscope (SEM), where the presence of soaps can be visualized through compositional contrast with the “healthy” paint. The dissolution of lead-containing pigments can be recognized in this SEM image by gray areas around brighter white particles that are unreacted lead white pigment

Soap formation has also been indicated as the cause of the increased transparency of paint films, which allows the preparatory drawing, the wood or canvas support, and/or the artists' alterations to become visible to the naked eye in some oil paintings.[7, 12–14] This is seen in Meyndert Hobbema’s Village Among Trees (1665) in the Frick Collection, where the dark pores from the wood support are visible to the naked eye. Microscopic analysis by Raman spectroscopy of samples removed from the blue paint in the sky revealed that the transparency is due to the presence of lead soaps.

Meyndert Hobbema (Dutch, 1638–1709). Village Among Trees (detail), 1655. Oil on oak panel, 30 x 43 1/2 in. (76.2 x 110.5 cm). The Frick Collection, New York, Henry Clay Frick Bequest (1902.1.73). This detail, before treatment, shows the transparency caused by soap formation that makes the dark pores of the wood grain visible

Despite their widespread occurrence, soap formations’ chemistry is not yet fully understood. The formation of soaps does not take place in all artworks containing the potentially reactive materials. What factors trigger the process, what the mechanisms are, and how the processes can be arrested or prevented are not yet known. Various theories have suggested that the phenomenon may result from peculiarities inherent in the artists’ materials and techniques, from conservation procedures, or from the objects’ exposure to environmental conditions such as high relative humidity and temperature, but these suggestions have not yet been thoroughly studied.[1, 2, 12, 14]

Method

Soaps have been characterized and identified in samples from works of art by microanalytical techniques, such as FTIR, secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), GC-MS, scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectrometry (SEM-EDS), micro-X-ray fluorescence, and Raman spectroscopy. However, not much is known about the local structure and the dynamics of soap formation.

Solid state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) allows us to obtain local structural information about lead soaps that cannot be accessed by other methods. The lead soaps are difficult to crystallize, so X-ray diffraction is not suitable, but they are insoluble, which makes ssNMR an adequate method to study them. In ssNMR, specific nuclei are excited in a magnetic field; how a particular spin responds depends on the local coordination environment. 13C and 207Pb nuclei are very sensitive to changes in local coordination and therefore the data from our experiments can tell us the identity of the lead soap and the coordination geometry. This information could also point to the reaction mechanisms between the lead-containing pigment and the binding medium. We have synthesized and examined the spectroscopical properties of lead carboxylates commonly found in soap aggregates: lead azelate, lead palmitate, and lead stearate, and we are currently studying model paint samples.

University of Delaware students Anna Murphy and Yao Yao using the solid-state NMR spectrometer

Results

We have collected ssNMR data on lead palmitate, lead stearate, and lead azelate at the NMR Facility in Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Delaware. The 13C spectra of these lead carboxylates show resonance doubling of sites close to the lead, indicating two possible coordinations of the fatty acid chain with the lead ion. This result is in agreement with a published crystal structure of lead azelate[15] that shows two different conformations of the fatty acid chain in the asymmetric unit, as well as with previously published 13C spectra of lead decanoate and lead stearate [16]. Since the crystal structures of lead palmitate and lead stearate are not known, these results provide us with a clue that these lead carboxylates may also have two different conformations of the fatty acid chain in the asymmetric unit. From 207Pb, NMR spectra we were able to determine the NMR parameters of the lead carboxylates. We have found that lead palmitate and stearate have very similar tensor components and lineshapes, which indicates a similar coordination environment. However, lead palmitate and stearate could not be distinguished in a mixture but could be distinguished from lead carbonate, a component in lead white pigment. Lead azelate has a larger span and a different skew than lead palmitate and stearate. This shows that lead azelate can be characterized, identified, and distinguished from lead palmitate, lead stearate, and lead carbonate in a paint mixture.

Conclusion

Understanding the nature of the chemical processes gives art conservators information on ways to slow, stop, and prevent the deterioration of unique works of art. The 13C and 207Pb solid state NMR spectra of these compounds have provided new structural information crucial to characterizing these components and their dynamics in model paint, and eventually in real paint samples. Current developments in probe design and sample holders will eventually make solid-state NMR a minimally invasive technique. The NMR studies presented here along with further development of 207Pb NMR methods can extend beyond cultural heritage and be applied to other lead-containing compounds, such as electronic and optoelectronic materials, superconducting materials, and environmentally contaminated materials.