The identification of the materials used for the ground preparations of paintings is of critical interest to scholars as certain materials can point to specific regions and schools of painting. Historically, a variety of inorganic materials, such as calcite and gypsum, bound with natural glues, have been used by artists to seal and protect the canvas support prior to the application of subsequent priming and paint layers containing drying oils.

Magnified paint sample from Our Lady of Valvanera (detail), ca. 1770–80. Peru, Cuzco. Oil and gold on canvas, 80 1/8 x 95 7/8 in. (203.4 x 243.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James Kung Wei Li, in memory of Ambassador and Mme Ti-Tsun Li, Republic of China, 2018 (2018.652.3)

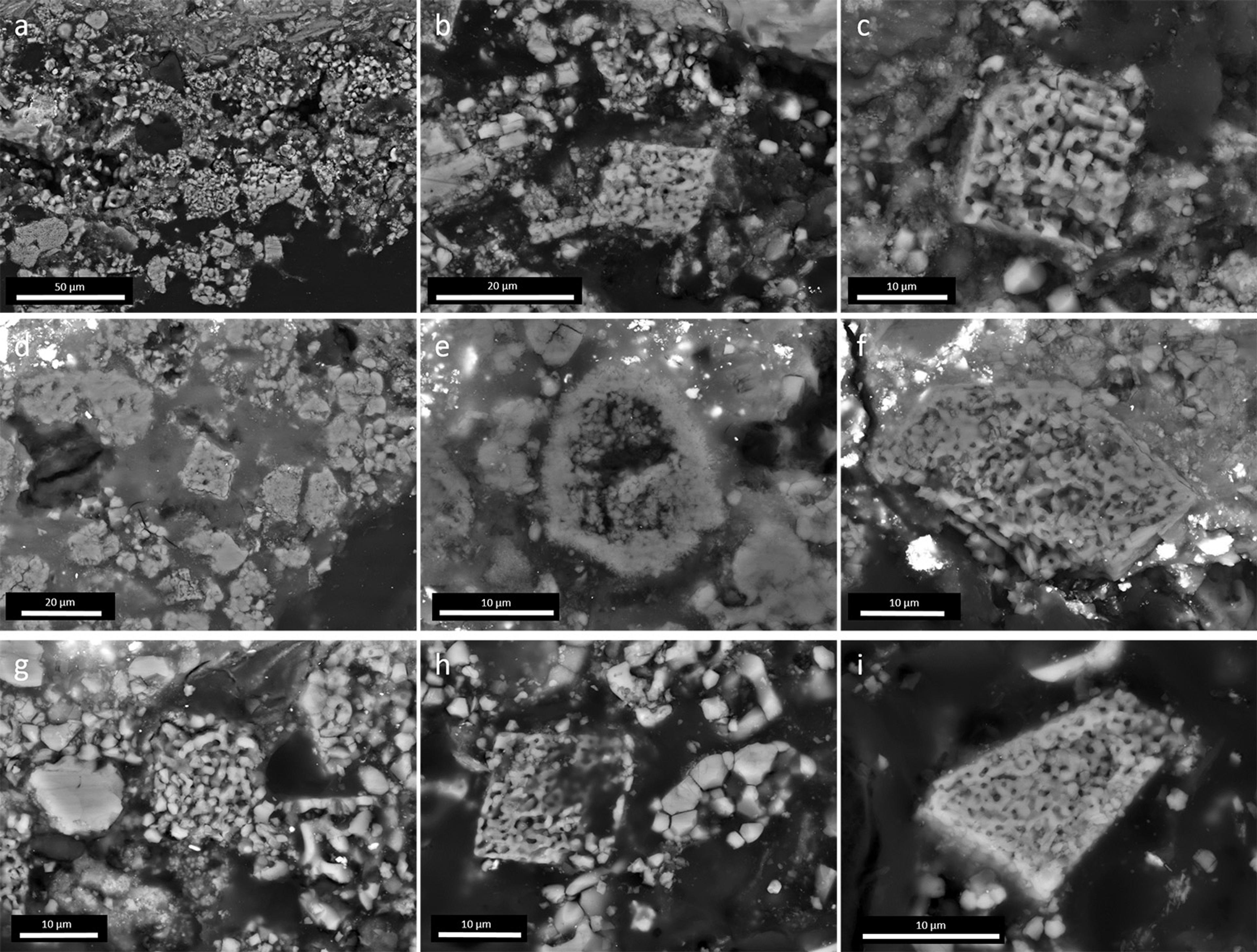

This is the case of a particular ash-based, calcite-rich material obtained as a byproduct of lye production. In a previous work, we provided unequivocal tools to identify these calcite particles from ashes in paint cross sections. We compared the morphology, texture and composition of calcite crystals, called pseudomorphs, found in laboratory ash to the crystals observed in the ground preparations of paintings.

The unique polygonal shapes and skeletal morphology of the pseudomorphs, as well as their abundance, make them ideal markers to recognize ash in ground layers, even if present in a small quantity.

BSE images showing calcite pseudomorph particles, most of them with skeletal structure, found in the ground layer of Velazquez’s Portrait of a Man (a–c) and Juan de Pareja (d–f), and of Villalpando’s Adoration of the Magi (g–i). Reproduced from “Painting with Recycled Materials: on the morphology of calcite pseudomorphs as evidence of the use of wood ash residues in Baroque paintings,” Federico Carò, Silvia A. Centeno, and Dorothy Mahon. Heritage Science, 2018, 6:3. doi.org/10.1186/s40494-018-0166-5.

The study focused on paintings by Diego Velázquez, completed in Madrid and Rome; by Luca Giordano, painted in Madrid and Naples; and by José Sánchez and Cristόbal de Villalpando, possibly painted in Mexico City and Puebla. We discovered that the practice of using ash in grounds, described in the Spanish treatises of Francesco Pacheco (1564–1638/1644) and Antonio Palomino (1655–1726), also occurred in Colonial Latin America. Our results indicate that ashes were used in different ways by Spanish and Latin American artists. Indeed, the application of a ground can be as personal as the finished product and variations within Spain and Mexico exist. We are now investigating local preparatory practices in a study of a larger number of works, with more diverse geographical origins and executed across a broader span of time.

Paintings from Colonial South America

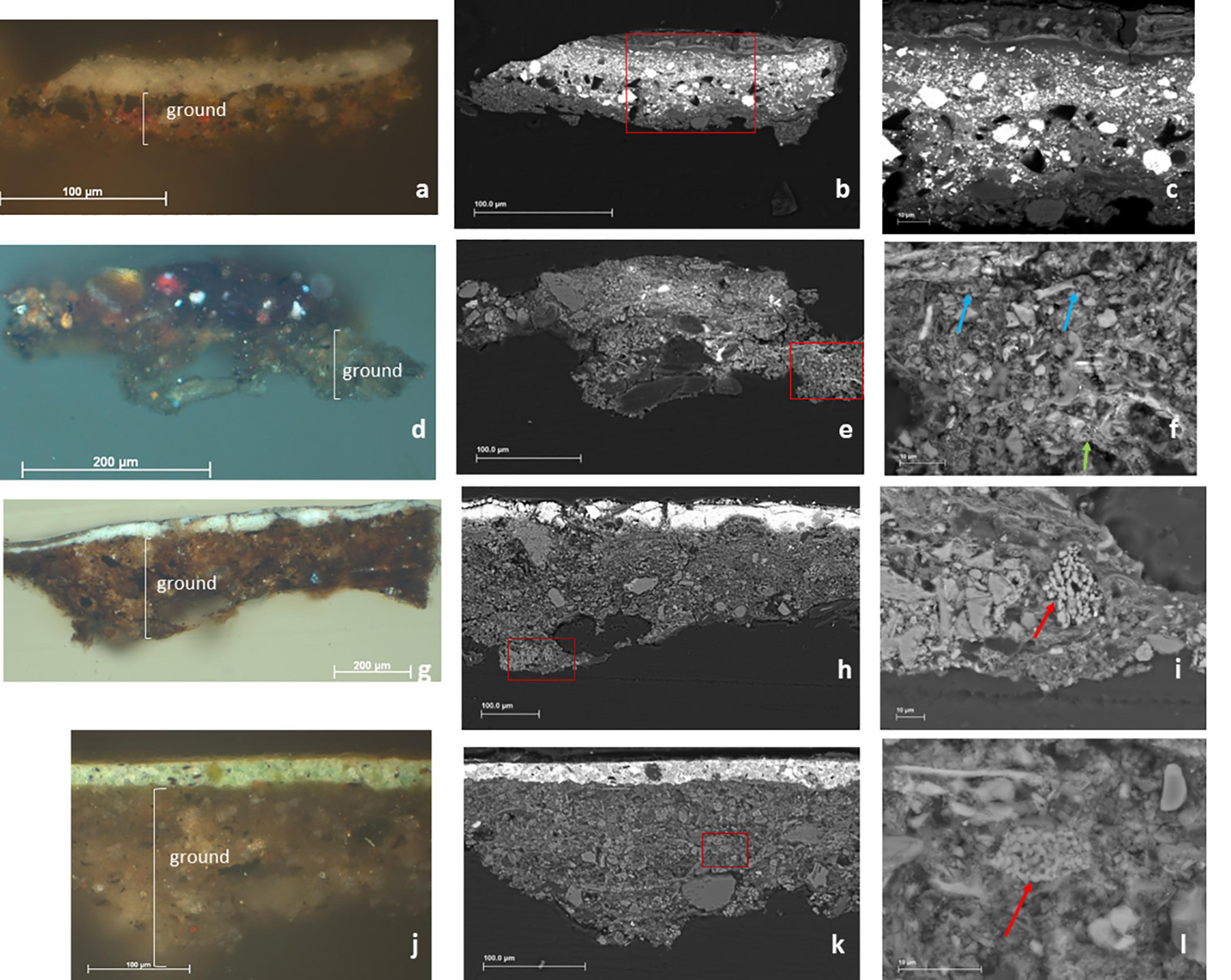

To answer the questions posed regarding the geographical extent of the use of ash in preparation layers, we analyzed the grounds of six paintings from colonial South America. The selection was from an outstanding donation of ten paintings by James Kung Wei Li and his family in celebration of the Museum’s 150th anniversary. These late 17th and 18th century paintings were created in the Viceroyalty of Peru and as a group, they are representative of the artistic production of the Cuzco School. Due to the limited presence of South American colonial paintings in the collection, these artworks are truly foundational to the museum. As is frequently the case with paintings from the region, they were mostly created by unknown artists. Therefore, the investigation of the materials and techniques employed in these works is pivotal to understanding artistic methods in the region.

Two of the Cuzco School paintings, part of the recent gift to The Met, during preliminary examination in the paintings conservation studio. Both Christ Carrying the Cross, called "The Lord of the Fall," (left) and Our Lady of Valvanera (right) were painted by unknown artists between 1770 and 1780

The grounds in the paintings vary in color from red and dark brown, to black. Five of these paintings have a heterogonous and complex composition, but only two of them have calcite particles with the typical morphology of plant ash origin. The characteristics of the grounds in these five paintings from South America are consistent with the use of unrefined ash rich in soil that may have been ground and sieved, but not leached as described in the Spanish treatises. As a consequence, calcite pseudomorphs are less abundant than in leached ash.

Photomicrographs of sample cross-sections taken with visible illumination (a, d, g, and i) and backscattered electron images (b, c, e, f, g, i, k, and i): The Soul of the Virgin Mary (a, 400x, b and c); Christ Carrying the Cross (d, 200x, e and f); Our Lady of Mercy (g, 100x, h and i); Saint Christopher (j, 400x, k and l). The red rectangles in b, e, h, and k indicate the areas where, respectively, the details c, f, i, and l were taken. Red arrows indicate calcite pseudomorphs, blue arrows glassy particles, and the green arrow the location of amorphous Si-rich particles

This is a novel contribution to the field of technical art history that provides analytical evidence about connections in artistic practice in the Baroque world. As an increasing number of paintings produced in Latin America, Spain, and other European countries are investigated, we hope that more patterns will begin to emerge to help us better understand how the use of ashes spread beyond Spain.