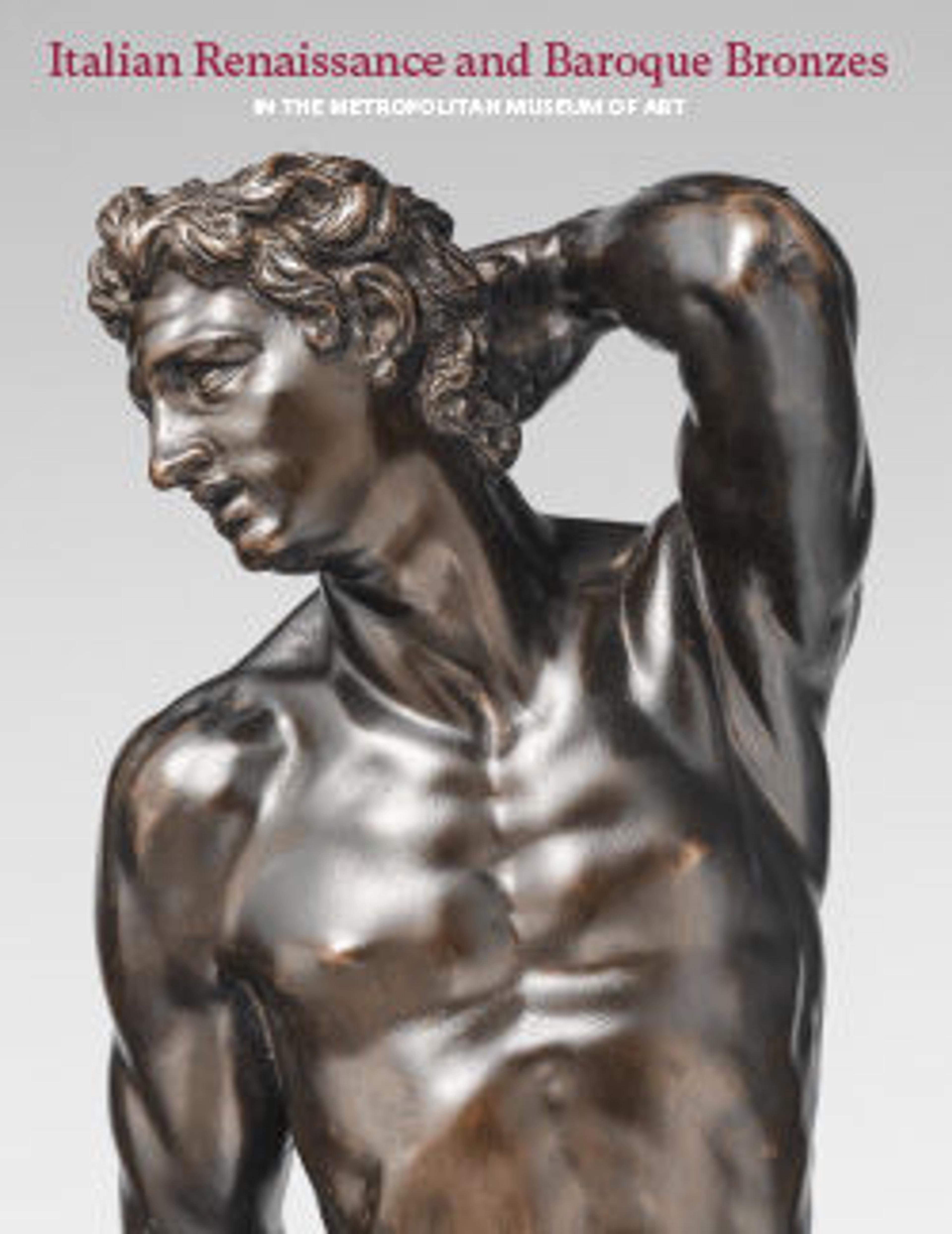

Andiron with figure of Mars (one of a pair)

The pair of andirons once belonged to Michael Friedsam, head of the B. Altman & Company department store in New York from 1913 until his death in 1931. Inspired perhaps by the example of his cousin, Benjamin Altman, founder of the company, Friedsam was a passionate collector, interested principally in Northern Renaissance and Baroque painting. Responding to the vogue for decorative objects in Gilded Age interiors, he also forayed into the field of Italian Renaissance bronzes, particularly those from Florence to Padua and Venice. His bequest to The Met, formalized in June 1930, included a large selection of bronze statuettes, from which curator Joseph Breck could make a considered selection of accessions for the museum.[1]

Described in the acquisition paperwork as “in the manner of Alessandro Vittoria,” these firedogs would have been considered elegant specimens of a type popular on the curiosités market in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (see also cats. 80, 82). Judging by the number of surviving examples, even excluding later casts and modern forgeries, the production of firedogs in cinquecento Venice was a lucrative business that continued well into the next century, buoyed by the constant recycling of famous sculptural models and prototypes.[2]

The Friedsam bronzes follow the typical tripartite scheme for these functional objects: a triangular base (for stability), a central section more or less articulated, and a crowning small statuette of a mythological or allegorical subject. Technical analysis conducted in 2001 confirms that the bases and central sections are composed of the same alloy. The heraldic oval at the center of the stem features an eagle, a striding lion, and a grid motif. The surmounting figures, Minerva and Mars, are known through numerous replicas, for instance, casts of the pair in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.[3] These versions are distinguished by variations in detail—the decoration of the breastplates, the helmets, surface finish—as well as production context, quality of execution, and dating. Taken together, they illuminate the dynamics of Venetian bronzeworking in the early modern period, by clarifying how celebrated inventions could be copied and adapted to different objects, often in the same workshop, based on time-honored formal and iconographic conventions.

Unfortunately, these conditions also make it very difficult to determine the maker of specific objects. In 1919, Leo Planiscig attributed the composite formula adapted for the two deities of the Friedsam andirons to the workshop of Danese Cattaneo.[4] More recently, they were related to Tiziano Aspetti’s shop.[5] Claudia Kryza-Gersch has placed the pair within the circle of Nicolò Roccatagliata around 1600: she underlined their high quality, evident as well in a bronze Mars and Minerva published by Alan Gibbon in 1990, then on the London market but present location unknown.[6]

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Friedsam Papers, MMA Archives.

2. Motture 2003.

3. Planiscig 1919, pp. 135–36, nos. 207, 208. Other casts of the pair can be found in the Palazzo Venezia, Rome (Santangelo 1964, p. 19), and the Hermitage, H-CK-543, 547 (Androsov 2007, pp. 171–73 nos. 185, 186). Another pair came to auction twice: Sotheby’s, London, July 3, 1985, lot 81, and Sotheby’s, New York, January 11, 1995, lot 84. A Mars, without a pendant, is in the Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 51.904 (Balogh 1975, vol. 1, p. 177), while a Minerva, missing an arm, is in the Offermann collection, Cologne (Brockhaus and Leinz 1994, p. 104, cat. 33). Two andirons of differing structure but topped by similar small figures are in the Museo Civico Medievale, Bologna, 1492 (D’Apuzzo 2017, pp. 216–20, no. 69a/b).

4. Planiscig 1919, pp. 135–36.

5. Gibbon 1990, p. TK; Brockhaus and Leinz 1994, p. 104, no. 33.

6. Claudia Kryza-Gersch, March 2001, ESDA/OF; Gibbon 1990, p. TK.

Described in the acquisition paperwork as “in the manner of Alessandro Vittoria,” these firedogs would have been considered elegant specimens of a type popular on the curiosités market in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (see also cats. 80, 82). Judging by the number of surviving examples, even excluding later casts and modern forgeries, the production of firedogs in cinquecento Venice was a lucrative business that continued well into the next century, buoyed by the constant recycling of famous sculptural models and prototypes.[2]

The Friedsam bronzes follow the typical tripartite scheme for these functional objects: a triangular base (for stability), a central section more or less articulated, and a crowning small statuette of a mythological or allegorical subject. Technical analysis conducted in 2001 confirms that the bases and central sections are composed of the same alloy. The heraldic oval at the center of the stem features an eagle, a striding lion, and a grid motif. The surmounting figures, Minerva and Mars, are known through numerous replicas, for instance, casts of the pair in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.[3] These versions are distinguished by variations in detail—the decoration of the breastplates, the helmets, surface finish—as well as production context, quality of execution, and dating. Taken together, they illuminate the dynamics of Venetian bronzeworking in the early modern period, by clarifying how celebrated inventions could be copied and adapted to different objects, often in the same workshop, based on time-honored formal and iconographic conventions.

Unfortunately, these conditions also make it very difficult to determine the maker of specific objects. In 1919, Leo Planiscig attributed the composite formula adapted for the two deities of the Friedsam andirons to the workshop of Danese Cattaneo.[4] More recently, they were related to Tiziano Aspetti’s shop.[5] Claudia Kryza-Gersch has placed the pair within the circle of Nicolò Roccatagliata around 1600: she underlined their high quality, evident as well in a bronze Mars and Minerva published by Alan Gibbon in 1990, then on the London market but present location unknown.[6]

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Friedsam Papers, MMA Archives.

2. Motture 2003.

3. Planiscig 1919, pp. 135–36, nos. 207, 208. Other casts of the pair can be found in the Palazzo Venezia, Rome (Santangelo 1964, p. 19), and the Hermitage, H-CK-543, 547 (Androsov 2007, pp. 171–73 nos. 185, 186). Another pair came to auction twice: Sotheby’s, London, July 3, 1985, lot 81, and Sotheby’s, New York, January 11, 1995, lot 84. A Mars, without a pendant, is in the Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 51.904 (Balogh 1975, vol. 1, p. 177), while a Minerva, missing an arm, is in the Offermann collection, Cologne (Brockhaus and Leinz 1994, p. 104, cat. 33). Two andirons of differing structure but topped by similar small figures are in the Museo Civico Medievale, Bologna, 1492 (D’Apuzzo 2017, pp. 216–20, no. 69a/b).

4. Planiscig 1919, pp. 135–36.

5. Gibbon 1990, p. TK; Brockhaus and Leinz 1994, p. 104, no. 33.

6. Claudia Kryza-Gersch, March 2001, ESDA/OF; Gibbon 1990, p. TK.

Artwork Details

- Title: Andiron with figure of Mars (one of a pair)

- Artist: Style of Danese Cattaneo (Italian, ca. 1512–1572)

- Date: early 17th century?

- Culture: Italian, Venice

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Height: 36 1/4 in. (92.1 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931

- Object Number: 32.100.188

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.