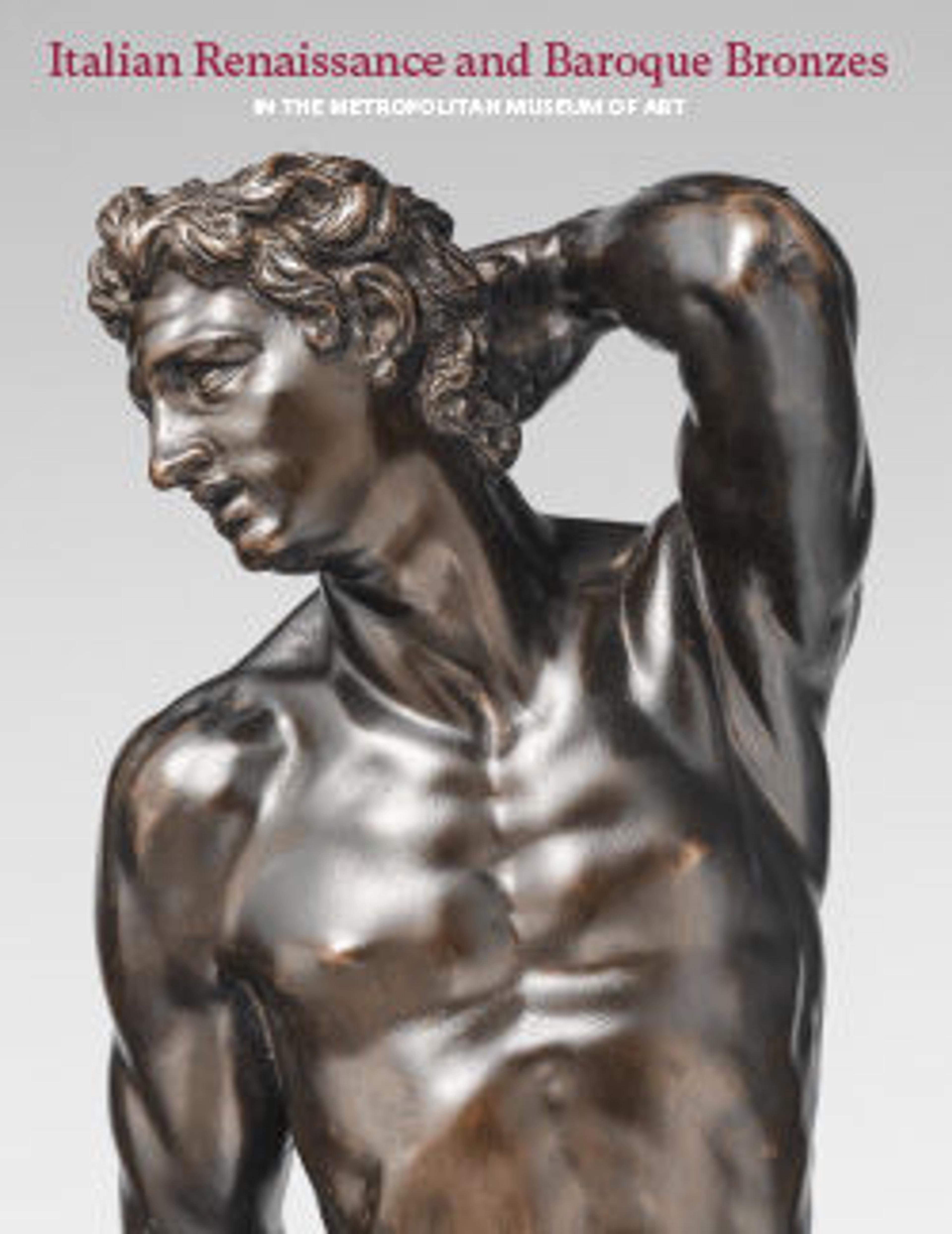

Ganymede with eagle and eaglet

To court Ganymede, a beautiful Trojan prince, Jupiter transformed himself into an eagle and flew the youth to Mount Olympus to serve him as cupbearer. This recurrent Renaissance theme was often interpreted as conferring divine sanction on homoerotic relations.[1]

In 1546, Benvenuto Cellini entered the dialogue when Cosimo I de’ Medici, grand duke of Tuscany, showed him an ancient Parian marble torso of a youth. Cellini offered to restore it but wanted the subject to evolve into a Ganymede. He thus supplied it with a head, a lower right leg, both feet, a base, and the companion eagle, the neck feathers of which the boy caresses with one hand. The other hand rather teasingly lifts a smaller, downy eaglet (fig. 105a).[2] The eaglet’s head and neck, missing in our copy, were once attached by a metal pin that remains on top.

The composition proved popular, and the Doccia porcelain works offered reductions in five sizes.[3] It is rarer in bronze. Our version is a rudimentary solid cast, unretouched except for the gilding of hair and feathers. The whole, like the Doccia output, retains the proportions of Cellini’s marble, which are remarkably normative for that Mannerist. Someone who wanted to recall the more familiar side of Cellini attenuated the legs of a statuette in the Frick (1916.2.42). The Met’s group has been called “much inferior” to the Frick’s, but not so: if ours is no great shakes as a bronze, its eagle is articulately feathered, especially admirably in back. The plumes of the other are barely demarcated.[4]

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Saslow 1986; Barkan 1991.

2. For a political interpretation of the marble’s iconography, see Allen 2013. The subject—a boy offering Jupiter a baby raptor?—makes little sense unless the eaglet is seen as a play on the word uccello (bird), then as now an allusion to the male member.

3. Lankheit 1982, p. 116. The boy in the large porcelain group by Gaspero Bruschi in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris (ibid., fig. 51), has a swath of drapery around his hips.

4. Another, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (44.587), is less curvaceous, has an oddly twisted neck, and lacks the eagle, and so does not form part of the discussion. Wilson 2001, pp. 254–55, fig. 11, suspects it is nineteenth century.

In 1546, Benvenuto Cellini entered the dialogue when Cosimo I de’ Medici, grand duke of Tuscany, showed him an ancient Parian marble torso of a youth. Cellini offered to restore it but wanted the subject to evolve into a Ganymede. He thus supplied it with a head, a lower right leg, both feet, a base, and the companion eagle, the neck feathers of which the boy caresses with one hand. The other hand rather teasingly lifts a smaller, downy eaglet (fig. 105a).[2] The eaglet’s head and neck, missing in our copy, were once attached by a metal pin that remains on top.

The composition proved popular, and the Doccia porcelain works offered reductions in five sizes.[3] It is rarer in bronze. Our version is a rudimentary solid cast, unretouched except for the gilding of hair and feathers. The whole, like the Doccia output, retains the proportions of Cellini’s marble, which are remarkably normative for that Mannerist. Someone who wanted to recall the more familiar side of Cellini attenuated the legs of a statuette in the Frick (1916.2.42). The Met’s group has been called “much inferior” to the Frick’s, but not so: if ours is no great shakes as a bronze, its eagle is articulately feathered, especially admirably in back. The plumes of the other are barely demarcated.[4]

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Saslow 1986; Barkan 1991.

2. For a political interpretation of the marble’s iconography, see Allen 2013. The subject—a boy offering Jupiter a baby raptor?—makes little sense unless the eaglet is seen as a play on the word uccello (bird), then as now an allusion to the male member.

3. Lankheit 1982, p. 116. The boy in the large porcelain group by Gaspero Bruschi in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris (ibid., fig. 51), has a swath of drapery around his hips.

4. Another, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (44.587), is less curvaceous, has an oddly twisted neck, and lacks the eagle, and so does not form part of the discussion. Wilson 2001, pp. 254–55, fig. 11, suspects it is nineteenth century.

Artwork Details

- Title: Ganymede with eagle and eaglet

- Artist: After a composition by Benvenuto Cellini (Italian, Florence 1500–1571 Florence)

- Date: probably 18th century

- Culture: Italian, Florence

- Medium: Bronze, partially oil-gilt

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 11 1/8 × 5 × 3 3/8 in., 10 lb. (28.3 × 12.7 × 8.6 cm, 4.5 kg)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1933

- Object Number: 33.58

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.