Anointment of the dead Christ

This relief entered The Met in the spring of 1955, a fortunate outcome following negotiations begun the previous fall. That November, the work was brought to the attention of curators Preston Remington and John Goldsmith Phillips by Ernst Günter Troche, former director of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, and a transplant to the West Coast following World War II.[1] At the time of its purchase, the bronze was in the collection of Barbara Herbert, a sculptor based in San Francisco.[2] Traveling to Paris around 1930, Herbert met the sculptor Alfred Boucher, a contemporary of Rodin and mentor to many younger artists. Boucher was a generous collector (if not an infallible connoisseur); in the late 1920s, he gifted to the Louvre a painting that then was believed to be an autograph Rembrandt self-portrait.[3] Herbert acquired a number of works from Boucher, including the Anointment, which Troche judged to be the most precious object in her collection.[4]

Initially skeptical, The Met’s curators were perhaps swayed by the expertise of Ulrich Middeldorf, who situated the relief in its proper historical context.[5] In 1596, Ferdinando I de’ Medici sent a “bronze ornament in relief” to the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem to serve as a precious encasement for the Stone of Unction. The commission was executed between 1588 and 1592. The encasement, comprised of six plaques depicting the Passion of Christ (from the Raising of the Savior’s Cross to the Resurrection), was cast in bronze by Domenico Portigiani after models by Pietro Francavilla and his master Giambologna. The latter’s contributions to the series are traditionally recognized as the Anointment and the Entombment, an attribution based entirely on stylistic considerations. Not only are these reliefs dramatically different from Francavilla’s in their compositional clarity and sculpted details, but their rhythmic designs correspond—in reduced form—to the general schemes employed in the waxes of the Acts of Francesco I, modeled by Giambologna around 1585–87 in preparation for their translation in gold for a stipo designed by Bernardo Buontalenti.[6]

Despite a fire that seriously damaged the church of the Holy Sepulchre in 1808, the Passion bronzes survived and are now installed—following an incorrect narrative sequence—on the altar of the Calvary Chapel (fig. 132a).[7] Based on Friedrich Kriegbaum’s photographic documentation, Middeldorf concluded that the relief in Herbert’s collection replicated a scene from the altar plaques. In addition, the Bode-Museum holds another complete Passion series, and individual scenes are held in the V&A and the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center.[8] The dimensions of all of these works roughly align with the Jerusalem reliefs (about a half braccio [ca. 29 cm] square).

A comparison of the Jerusalem and Met Anointments shows the same configuration of figures arrayed against barren hills with a town in the background, and a similar restrained modeling of garments. Discrepancies in details may be useful in constructing a stemma codicum for the known replicas. In the Jerusalem and Berlin plaques, the last figure on the right is barefoot, while in ours he wears misshapen shoes. In our bronze again, the hat of the last figure at left is simplified and flattened, and the square format and frame is more summary. Perhaps the founder depended upon an overused model (or another cast), one that translated details or a peripheral element like the surround less precisely. This would suggest a much later dating for our plaque than the Holy Sepulchre series or even the Bode reliefs, themselves considered rather rough derivations.[9] The identification of our Anointment with one formerly belonging to the Salviati family in Florence, based on the testimony of Francesco Bocchi, remains speculative.[10] We cannot rule out the possibility that The Met relief was once part of a larger series: an example of an Entombment in the collection of Michael Hall was published in 1998.[11]

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Letter from Troche to Remington, dated November 30, 1954, ESDAOF.

2. For Herbert’s biography, see the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, at https://doi.org/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00086354.

3. Louvre, R.F. 2667 bis; see Coppier 1927 and Foucart 1982, p. 12.

4. Letter from Troche to Phillips, dated April 14, 1955, ESDA/OF.

5. Middeldorf tapped the research of Friedrich Kriegbaum (1927) on cinquecento Florentine sculpture. Letter from Troche to Phillips, dated March 28, 1955, ESDA/OF.

6. For a discussion of the Medici commission and the entire series of plaques, see Ronen 1970. For Francavilla’s reliefs, see Donatella Pegazzano in Fumagalli et al. 2001, pp. 144–46, cat. 23. For the attribution to Giambologna, see Kriegbaum 1927; Dhanens 1956, pp. 269–70, and C. Avery and Radcliffe 1978, p. 159, cat. 28 (rejected by Waźbiński 1984). For Giambologna’s Acts, see Barbara Bertelli in Paolozzi Strozzi and Zikos 2006, pp. 226–31, cats. 33–35.

7. Bange 1932, p. 23.

8. Bode-Museum, 7247–7250; V&A, 67-1866 (Entombment); Loeb Art Center, 1963.9 (Resurrection; see Vassar College 1982, p. 38).

9. C. Avery and Radcliffe 1978, pp. 159, 215–16; see also Pegazzano in Fumagalli et al. 2001, pp. 144–46.

10. Bocchi 1591, p. 185; Bocchi and Cinelli 1677, p. 371; Dhanens 1956, p. 270.

11. C. Avery and Hall 1998, p. 106, cat. 36.

Initially skeptical, The Met’s curators were perhaps swayed by the expertise of Ulrich Middeldorf, who situated the relief in its proper historical context.[5] In 1596, Ferdinando I de’ Medici sent a “bronze ornament in relief” to the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem to serve as a precious encasement for the Stone of Unction. The commission was executed between 1588 and 1592. The encasement, comprised of six plaques depicting the Passion of Christ (from the Raising of the Savior’s Cross to the Resurrection), was cast in bronze by Domenico Portigiani after models by Pietro Francavilla and his master Giambologna. The latter’s contributions to the series are traditionally recognized as the Anointment and the Entombment, an attribution based entirely on stylistic considerations. Not only are these reliefs dramatically different from Francavilla’s in their compositional clarity and sculpted details, but their rhythmic designs correspond—in reduced form—to the general schemes employed in the waxes of the Acts of Francesco I, modeled by Giambologna around 1585–87 in preparation for their translation in gold for a stipo designed by Bernardo Buontalenti.[6]

Despite a fire that seriously damaged the church of the Holy Sepulchre in 1808, the Passion bronzes survived and are now installed—following an incorrect narrative sequence—on the altar of the Calvary Chapel (fig. 132a).[7] Based on Friedrich Kriegbaum’s photographic documentation, Middeldorf concluded that the relief in Herbert’s collection replicated a scene from the altar plaques. In addition, the Bode-Museum holds another complete Passion series, and individual scenes are held in the V&A and the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center.[8] The dimensions of all of these works roughly align with the Jerusalem reliefs (about a half braccio [ca. 29 cm] square).

A comparison of the Jerusalem and Met Anointments shows the same configuration of figures arrayed against barren hills with a town in the background, and a similar restrained modeling of garments. Discrepancies in details may be useful in constructing a stemma codicum for the known replicas. In the Jerusalem and Berlin plaques, the last figure on the right is barefoot, while in ours he wears misshapen shoes. In our bronze again, the hat of the last figure at left is simplified and flattened, and the square format and frame is more summary. Perhaps the founder depended upon an overused model (or another cast), one that translated details or a peripheral element like the surround less precisely. This would suggest a much later dating for our plaque than the Holy Sepulchre series or even the Bode reliefs, themselves considered rather rough derivations.[9] The identification of our Anointment with one formerly belonging to the Salviati family in Florence, based on the testimony of Francesco Bocchi, remains speculative.[10] We cannot rule out the possibility that The Met relief was once part of a larger series: an example of an Entombment in the collection of Michael Hall was published in 1998.[11]

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Letter from Troche to Remington, dated November 30, 1954, ESDAOF.

2. For Herbert’s biography, see the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, at https://doi.org/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00086354.

3. Louvre, R.F. 2667 bis; see Coppier 1927 and Foucart 1982, p. 12.

4. Letter from Troche to Phillips, dated April 14, 1955, ESDA/OF.

5. Middeldorf tapped the research of Friedrich Kriegbaum (1927) on cinquecento Florentine sculpture. Letter from Troche to Phillips, dated March 28, 1955, ESDA/OF.

6. For a discussion of the Medici commission and the entire series of plaques, see Ronen 1970. For Francavilla’s reliefs, see Donatella Pegazzano in Fumagalli et al. 2001, pp. 144–46, cat. 23. For the attribution to Giambologna, see Kriegbaum 1927; Dhanens 1956, pp. 269–70, and C. Avery and Radcliffe 1978, p. 159, cat. 28 (rejected by Waźbiński 1984). For Giambologna’s Acts, see Barbara Bertelli in Paolozzi Strozzi and Zikos 2006, pp. 226–31, cats. 33–35.

7. Bange 1932, p. 23.

8. Bode-Museum, 7247–7250; V&A, 67-1866 (Entombment); Loeb Art Center, 1963.9 (Resurrection; see Vassar College 1982, p. 38).

9. C. Avery and Radcliffe 1978, pp. 159, 215–16; see also Pegazzano in Fumagalli et al. 2001, pp. 144–46.

10. Bocchi 1591, p. 185; Bocchi and Cinelli 1677, p. 371; Dhanens 1956, p. 270.

11. C. Avery and Hall 1998, p. 106, cat. 36.

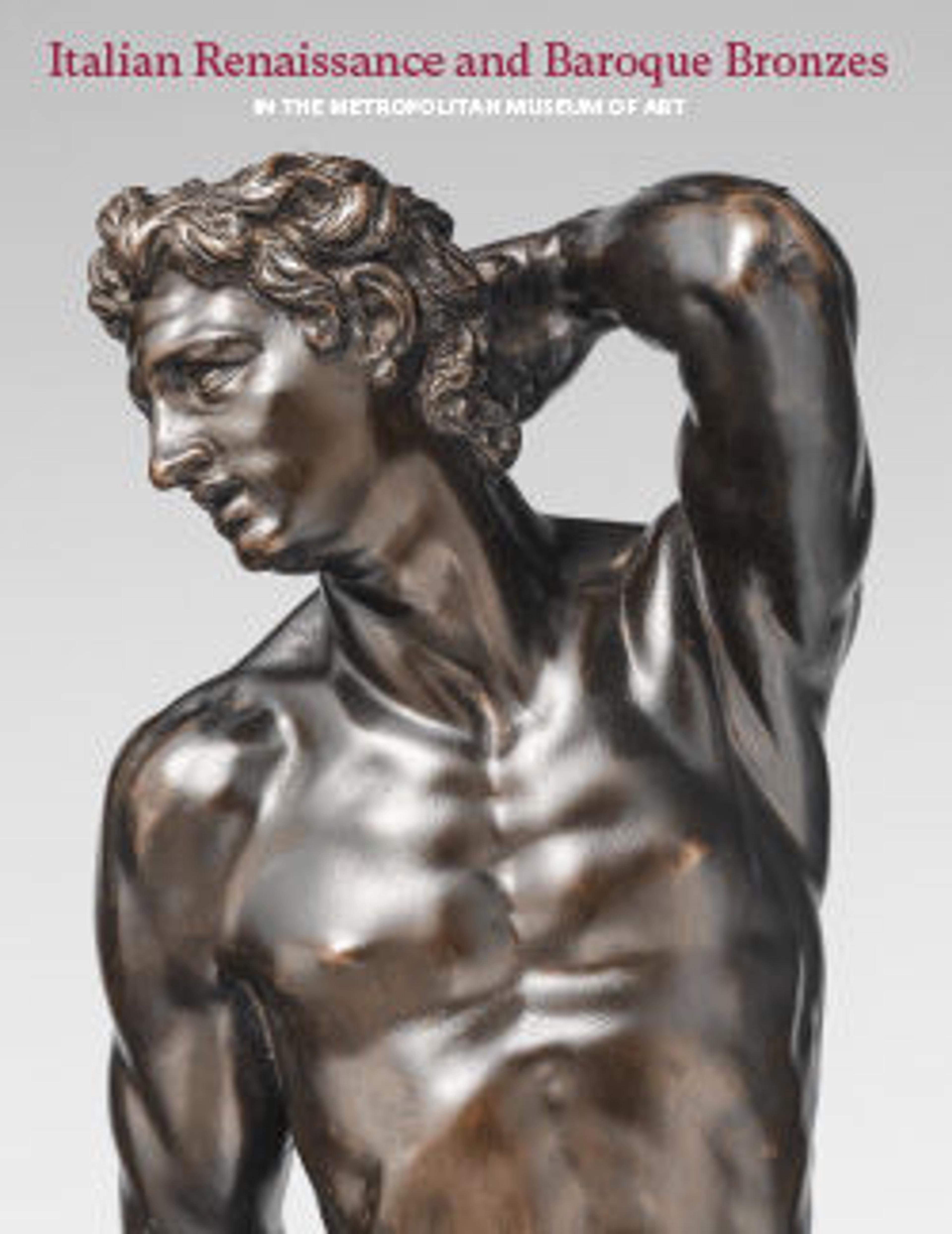

Artwork Details

- Title: Anointment of the dead Christ

- Maker: Probably cast by Fra Domenico Portigiani

- Artist: After a model by Giambologna (Netherlandish, Douai 1529–1608 Florence)

- Date: 17th century?

- Culture: Italian, Florence

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall: 10 7/16 × 11 1/4 in. (26.5 × 28.6 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Edith Perry Chapman Fund, 1955

- Object Number: 55.72

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.