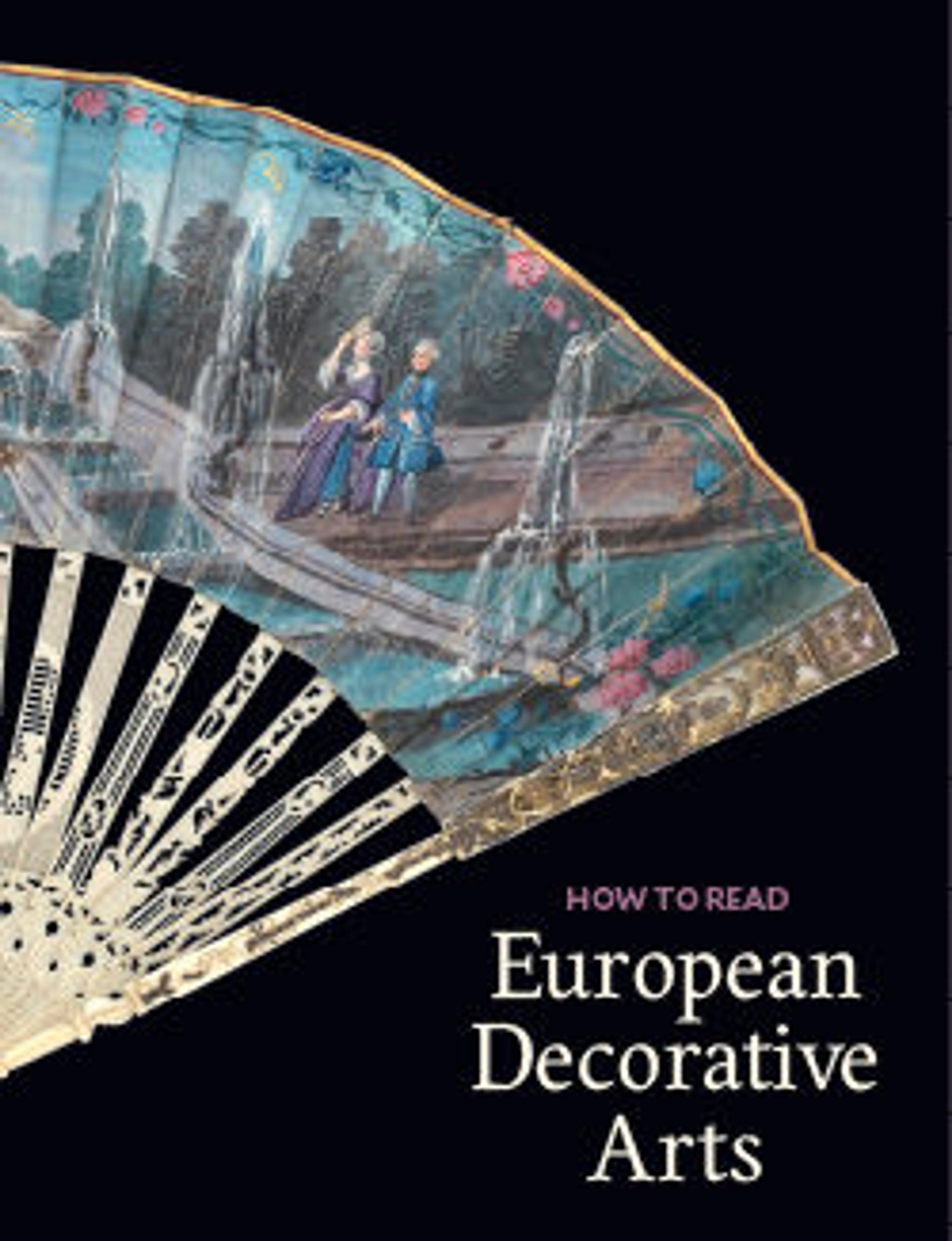

Mantel clock with musical movement

In Paris in January 1775, a display of three marvelous automata created a sensation. One automaton wrote a sentence of forty letters; the other automaton drew portraits of the King Louis XV, King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, and a small dog; and the third automaton played a keyboard instrument. These nearly life-size automata were the creation of Swiss clockmakers Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721–1790) and his son Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz (1752–1791), with assistance from the mechanician Jean-Frédéric Leschot (1746–1824); their association would last until the end of the eighteenth century.[1] The lady musician, who not only played five tunes, but also batted her eyes and turned her head from side to side, no doubt fueled French enthusiasm for musical automata. In fact, about the end of 1784 the French queen acquired a musical automaton playing a dulcimer, which was made by the Germans David Roentgen (1743–1807) and Christian I Kinzing (1707–1804) of Neuwied.[2]

Thus, it is understandable that one of the contributing authors to the Memoires secrets pour servir a l’histoire de la Republique des Lettres en France, depuis mdcclxii jusqu’a nos jours (Secret Memoirs Serving as a History of the Republic of Letters in France from 1762 until Our Day), a thirty-six volume record of notable events literary, scientific, and otherwise, paid a visit to the clockmaker Jean-Baptiste-André Furet (ca. 1720–1807) on July 4, 1784, and in whose shop three clocks of special interest were seen.[3] The author, who was probably Barthélemy- François- Josephy Mouffle d’Angerville (1728–1795), was impressed with the first clock, in part, because of its beautifully ornamented case that included the bust of an African woman wearing long earrings, but also because when one earring was pulled, the hour appeared in her right eye and the minute in her left. When the other earring was pulled, the organ played six different airs. The second clock, a hanging birdcage with a clock dial on its bottom, was almost certainly one of the variety for which the Jaquet- Droz et Leschot firm was well known. Indeed, in a Parisian trade publication from 1786, the mechanical musician and the birdcage clocks with avian automata were described as precious works to be obtained from “Monsieur Droz, the celebrated mechanician of Neuchâtel.”[4] The third clock, now lesser known, was a terrestrial globe that displayed the time in Paris and numerous other places around the world.

The Museum’s clock more or less matches the description of the first clock. The case of the clock consists of the bust of an African woman, perhaps a princess, as she has sometimes been called, resting on a black-and-white marble base that is supported by six gilded-bronze feet. Details of the Neoclassical ornament that adorns the case have been exhaustively described by the Metropolitan Museum’s late Curator Emeritus James Parker in the catalogue of the Samuel H. Kress Collection.[5] The sculptor who provided the model for the bust, with its exquisite floral swag, bow and arrows, and feather-decorated cap, remains unknown. Nor is it known who executed the decorative plaque on the front of the base, with its procession of child huntsmen, or the two winged cherubs perched precariously on either side. The matte and burnished surface of the gilded-bronze elements is meticulously finished, but the lacquer on the skin of the bust has suffered extensive deterioration.

The time-telling mechanism of the clock is related to that of the revolving dials that had recently become the fashion for French clocks during this period, and especially but not exclusively, favored by the Paris workshop of the Lepaute family (see 29.180.2 in this volume). Essentially, the mechanism in Furet’s clock consists of an arbor with two revolving wheels, which are attached vertically instead of horizontally, the more common construction. One wheel is enameled with the hours in roman numerals; the other wheel with the minutes in Arabic numerals by twos. The wheels are concealed inside the head of the figure, and for most of the time they are completely invisible and covered by shutters. The gearing for the two wheels is attached to two shafts that are in turn driven by a movement containing a single train with a verge escapement and spring balance, which is concealed inside the shoulders of the figure. Its spring is wound through a hole in the back of one shoulder, and a second hole in the other shoulder permits adjustments to the setting of the hours and minutes.

The base of the clock houses a spring-driven cylinder organ that has been identified by curator Jan Jaap L. Haspels as a type described by Dom François Bedos de Celles (1709–1779), a master builder of French pipe organs and Benedictine monk, in a treatise on the construction of organs titled L’art du facteur d’orgues (The Art of the Organ Builder), published in Paris in four volumes between 1766 and 1778 (fig. 51).[6] Haspels noted that the author of the treatise believed that a spring-driven cylinder organ could support only one rank of ten pipes, but recognized that with the application of certain devices, or transmissions, enough power could be supplied to operate organs with as many as three ranks of pipes. One of these devices is to be found in the Museum’s clock in which the entire musical train is driven by two barrels containing mainsprings that act in tandem to produce greater force on a single fusee. Together, the two springs power a bellows and two ranks of pipes with fifteen keys. The music played by the organ that closely resembles the cylinder organ found in clocks made by the firm of Jaquet-Droz et Leschot has not been studied.[7]

It is quite likely that the clock was originally made to open the eye shutters and play a selected tune on the hour and to shut them again when the tune stopped, but the connection for activating the music no longer exists. The hours and minutes can still be seen by pulling at will the earring on the right side of the figure; the hours appear in the left eye and the minutes in the right eye. The earring on the left side originally activated the cylinder organ.

It cannot be certain that the Museum’s clock was the one described by the author of the entry in the Memoires secrets, because at least three other examples of the model are known. One, now in a private collection in Paris, was acquired for Marie Antoinette (1755–1793) by Thierry de Ville d’Avray (1732–1792), the director general of the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne (or keeper of the Royal Furniture and Moveable Possessions), who apparently kept the clock in his office for his own amusement and had the mechanism repaired several times between 1787 and 1792, until the French Revolution put an end to such amusements.[8]

A second example, this one signed “Le pine Her du Roy AParis 4195” (Jean-Antoine Lépine [1720–1814]), is in the British Royal Collection Trust, where it has been since before 1807 when another royal clockmaker, Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy (1780–1854), cleaned and refurbished the movement and regilded parts of the case.[9] This clock is nearly an exact duplicate of the Metropolitan Museum’s clock, so closely related that the author of the exhaustive study of Lépine’s work, Adolphe Chapiro, has attributed the clock to Furet regardless of the Lépine signature.[10] It seems likely, therefore, that either Furet supplied the equally busy and highly successful Lépine with the entire clock, or they each patronized the same subcontractors.

Parker reported the existence of another clock in the private collection of Mrs. Herbert A. May (formerly Marjorie Merriweather Post,[11] best known for her collection of Russian decorative arts) in Washington, D.C., and a fourth clock with a movement signed “J.S. Bourdier, 1817 AParis” appeared on the Paris auction market in 2007.[12] The clockmaker, Jean-Simon Bourdier (active 1787–1829), is known as a maker of ingenious musical clocks and automata.[13]

The clockmaker Furet, who signed the Metropolitan Museum’s clock, was one of the very few clockmakers who were visited by the authors of the Memoires secrets. He belonged to the third generation of Furets who were clockmakers in Paris, the earliest being André, whose shop was recorded in the rue des Gesvres in 1699. His son Jean-André became a master clockmaker in 1710, and his son Jean- Baptiste-André was born about 1720. Jean-Baptiste-André was made a master clockmaker in 1746, and a year later, he is recorded with his father at an establishment in the rue Saint- Honoré, presumably the one visited by Mouffle d’Angerville. By 1758, he had been granted a royal appointment (Horloger Ordinaire du Roi pour sa Bibliothèque [Clockmaker to the King and for His Library]), and about 1784 or 1785, he briefly became an associate of the Spanish clockmaker François- Antoine Godon (ca. 1740–1800).[14]

According to historian Jean-Dominique Augarde, Furet ceased paying his bills in 1785, and by March 4, 1786, he was bankrupt, declaring a stock of ninety-eight clocks valued at 63,903 livres, including one “African princess” (Tete de negresse) clock. There were more than ninety creditors, and a list reveals that Furet was subcontracting most of his production by the time of his bankruptcy. More than a third of the total was owed to Swiss suppliers and clockmakers.[15] This record strengthens the evidence to be seen by examining the cylinder organ and probably also the movement inside of the Metropolitan Museum’s clock, suggesting that both Furet and Lépine, who signed the clock now in the British Royal Collection Trust, did indeed obtain their movements from the same Swiss supplier.

Sold in 1881 at the Paris sale of the collection of Léopold Double,16 the Metropolitan Museum’s clock was later owned by the Marquis de Lambertie and by C. Ledyard Blair of Peapack, New Jersey.[17] cv / jhl

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] All three automata are now in the Musee des Beaux-Arts in Neuchatel, Switzerland. See Chapuis and Droz 1958, pp. 279–83, and pl. 1; Droz 1971. For further illustrations and discussion of the mechanism of the musician, see Jan Jaap L. Haspels in Royal Music Machines 2006, pp. 239–43, no. 47.

[2] D. Fabian 1984, p. 345, no. 92; Haspels in Royal Music Machines 2006, pp. 182–86, no. 33; Koeppe 2012, pp. 146–48, no. 38.

[3] Mémoires secrets 1786, p. 78. The Mémoires secrets are thought to have been started by Louis-Petit de Bachaumont (1690–1771).

[4] “M. Droz, celebre mechanicien de Neuf-Chatel”; Tablettes royale de renommée 1786, unpag. (“Nouvel etalon, ou Mesure universelle”).

[5] James Parker in Dauterman, Parker, and Standen 1964, pp. 268–72, no. 65, and figs. 226–28.

[6] See Haspels 1987, pp. 69–79, and pls. 107–9.

[7] Haspels 1994, pp. 58–59.

[8] Christian Baulez in Marie-Antoinette 2008, p. 210, no. 149.

[9] Jagger 1983, pp. 161–63. Cedric Jagger suggested that the clock may have been bought in 1790 by King George III’s eldest son, later to become King George IV (1765–1820).

[10] Chapiro 1988, p. 231.

[11] Parker in Dauterman, Parker, and Standen 1964, p. 269.

[12] See Rouge 2008, p. 85.

[13] Tardy 1971–72, vol. 1, p. 74; Augarde 1996, pp. 285, 287.

[14] Tardy 1971–72, vol. 1, pp. 240–41; Augarde 1996, pp. 317–18.

[15] Augarde 1996, pp. 317–18.

[16] Collection Double 1881, p. 86, no. 274.

[17] Parker in Dauterman, Parker, and Standen 1964, pp. 269, 272.

Thus, it is understandable that one of the contributing authors to the Memoires secrets pour servir a l’histoire de la Republique des Lettres en France, depuis mdcclxii jusqu’a nos jours (Secret Memoirs Serving as a History of the Republic of Letters in France from 1762 until Our Day), a thirty-six volume record of notable events literary, scientific, and otherwise, paid a visit to the clockmaker Jean-Baptiste-André Furet (ca. 1720–1807) on July 4, 1784, and in whose shop three clocks of special interest were seen.[3] The author, who was probably Barthélemy- François- Josephy Mouffle d’Angerville (1728–1795), was impressed with the first clock, in part, because of its beautifully ornamented case that included the bust of an African woman wearing long earrings, but also because when one earring was pulled, the hour appeared in her right eye and the minute in her left. When the other earring was pulled, the organ played six different airs. The second clock, a hanging birdcage with a clock dial on its bottom, was almost certainly one of the variety for which the Jaquet- Droz et Leschot firm was well known. Indeed, in a Parisian trade publication from 1786, the mechanical musician and the birdcage clocks with avian automata were described as precious works to be obtained from “Monsieur Droz, the celebrated mechanician of Neuchâtel.”[4] The third clock, now lesser known, was a terrestrial globe that displayed the time in Paris and numerous other places around the world.

The Museum’s clock more or less matches the description of the first clock. The case of the clock consists of the bust of an African woman, perhaps a princess, as she has sometimes been called, resting on a black-and-white marble base that is supported by six gilded-bronze feet. Details of the Neoclassical ornament that adorns the case have been exhaustively described by the Metropolitan Museum’s late Curator Emeritus James Parker in the catalogue of the Samuel H. Kress Collection.[5] The sculptor who provided the model for the bust, with its exquisite floral swag, bow and arrows, and feather-decorated cap, remains unknown. Nor is it known who executed the decorative plaque on the front of the base, with its procession of child huntsmen, or the two winged cherubs perched precariously on either side. The matte and burnished surface of the gilded-bronze elements is meticulously finished, but the lacquer on the skin of the bust has suffered extensive deterioration.

The time-telling mechanism of the clock is related to that of the revolving dials that had recently become the fashion for French clocks during this period, and especially but not exclusively, favored by the Paris workshop of the Lepaute family (see 29.180.2 in this volume). Essentially, the mechanism in Furet’s clock consists of an arbor with two revolving wheels, which are attached vertically instead of horizontally, the more common construction. One wheel is enameled with the hours in roman numerals; the other wheel with the minutes in Arabic numerals by twos. The wheels are concealed inside the head of the figure, and for most of the time they are completely invisible and covered by shutters. The gearing for the two wheels is attached to two shafts that are in turn driven by a movement containing a single train with a verge escapement and spring balance, which is concealed inside the shoulders of the figure. Its spring is wound through a hole in the back of one shoulder, and a second hole in the other shoulder permits adjustments to the setting of the hours and minutes.

The base of the clock houses a spring-driven cylinder organ that has been identified by curator Jan Jaap L. Haspels as a type described by Dom François Bedos de Celles (1709–1779), a master builder of French pipe organs and Benedictine monk, in a treatise on the construction of organs titled L’art du facteur d’orgues (The Art of the Organ Builder), published in Paris in four volumes between 1766 and 1778 (fig. 51).[6] Haspels noted that the author of the treatise believed that a spring-driven cylinder organ could support only one rank of ten pipes, but recognized that with the application of certain devices, or transmissions, enough power could be supplied to operate organs with as many as three ranks of pipes. One of these devices is to be found in the Museum’s clock in which the entire musical train is driven by two barrels containing mainsprings that act in tandem to produce greater force on a single fusee. Together, the two springs power a bellows and two ranks of pipes with fifteen keys. The music played by the organ that closely resembles the cylinder organ found in clocks made by the firm of Jaquet-Droz et Leschot has not been studied.[7]

It is quite likely that the clock was originally made to open the eye shutters and play a selected tune on the hour and to shut them again when the tune stopped, but the connection for activating the music no longer exists. The hours and minutes can still be seen by pulling at will the earring on the right side of the figure; the hours appear in the left eye and the minutes in the right eye. The earring on the left side originally activated the cylinder organ.

It cannot be certain that the Museum’s clock was the one described by the author of the entry in the Memoires secrets, because at least three other examples of the model are known. One, now in a private collection in Paris, was acquired for Marie Antoinette (1755–1793) by Thierry de Ville d’Avray (1732–1792), the director general of the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne (or keeper of the Royal Furniture and Moveable Possessions), who apparently kept the clock in his office for his own amusement and had the mechanism repaired several times between 1787 and 1792, until the French Revolution put an end to such amusements.[8]

A second example, this one signed “Le pine Her du Roy AParis 4195” (Jean-Antoine Lépine [1720–1814]), is in the British Royal Collection Trust, where it has been since before 1807 when another royal clockmaker, Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy (1780–1854), cleaned and refurbished the movement and regilded parts of the case.[9] This clock is nearly an exact duplicate of the Metropolitan Museum’s clock, so closely related that the author of the exhaustive study of Lépine’s work, Adolphe Chapiro, has attributed the clock to Furet regardless of the Lépine signature.[10] It seems likely, therefore, that either Furet supplied the equally busy and highly successful Lépine with the entire clock, or they each patronized the same subcontractors.

Parker reported the existence of another clock in the private collection of Mrs. Herbert A. May (formerly Marjorie Merriweather Post,[11] best known for her collection of Russian decorative arts) in Washington, D.C., and a fourth clock with a movement signed “J.S. Bourdier, 1817 AParis” appeared on the Paris auction market in 2007.[12] The clockmaker, Jean-Simon Bourdier (active 1787–1829), is known as a maker of ingenious musical clocks and automata.[13]

The clockmaker Furet, who signed the Metropolitan Museum’s clock, was one of the very few clockmakers who were visited by the authors of the Memoires secrets. He belonged to the third generation of Furets who were clockmakers in Paris, the earliest being André, whose shop was recorded in the rue des Gesvres in 1699. His son Jean-André became a master clockmaker in 1710, and his son Jean- Baptiste-André was born about 1720. Jean-Baptiste-André was made a master clockmaker in 1746, and a year later, he is recorded with his father at an establishment in the rue Saint- Honoré, presumably the one visited by Mouffle d’Angerville. By 1758, he had been granted a royal appointment (Horloger Ordinaire du Roi pour sa Bibliothèque [Clockmaker to the King and for His Library]), and about 1784 or 1785, he briefly became an associate of the Spanish clockmaker François- Antoine Godon (ca. 1740–1800).[14]

According to historian Jean-Dominique Augarde, Furet ceased paying his bills in 1785, and by March 4, 1786, he was bankrupt, declaring a stock of ninety-eight clocks valued at 63,903 livres, including one “African princess” (Tete de negresse) clock. There were more than ninety creditors, and a list reveals that Furet was subcontracting most of his production by the time of his bankruptcy. More than a third of the total was owed to Swiss suppliers and clockmakers.[15] This record strengthens the evidence to be seen by examining the cylinder organ and probably also the movement inside of the Metropolitan Museum’s clock, suggesting that both Furet and Lépine, who signed the clock now in the British Royal Collection Trust, did indeed obtain their movements from the same Swiss supplier.

Sold in 1881 at the Paris sale of the collection of Léopold Double,16 the Metropolitan Museum’s clock was later owned by the Marquis de Lambertie and by C. Ledyard Blair of Peapack, New Jersey.[17] cv / jhl

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] All three automata are now in the Musee des Beaux-Arts in Neuchatel, Switzerland. See Chapuis and Droz 1958, pp. 279–83, and pl. 1; Droz 1971. For further illustrations and discussion of the mechanism of the musician, see Jan Jaap L. Haspels in Royal Music Machines 2006, pp. 239–43, no. 47.

[2] D. Fabian 1984, p. 345, no. 92; Haspels in Royal Music Machines 2006, pp. 182–86, no. 33; Koeppe 2012, pp. 146–48, no. 38.

[3] Mémoires secrets 1786, p. 78. The Mémoires secrets are thought to have been started by Louis-Petit de Bachaumont (1690–1771).

[4] “M. Droz, celebre mechanicien de Neuf-Chatel”; Tablettes royale de renommée 1786, unpag. (“Nouvel etalon, ou Mesure universelle”).

[5] James Parker in Dauterman, Parker, and Standen 1964, pp. 268–72, no. 65, and figs. 226–28.

[6] See Haspels 1987, pp. 69–79, and pls. 107–9.

[7] Haspels 1994, pp. 58–59.

[8] Christian Baulez in Marie-Antoinette 2008, p. 210, no. 149.

[9] Jagger 1983, pp. 161–63. Cedric Jagger suggested that the clock may have been bought in 1790 by King George III’s eldest son, later to become King George IV (1765–1820).

[10] Chapiro 1988, p. 231.

[11] Parker in Dauterman, Parker, and Standen 1964, p. 269.

[12] See Rouge 2008, p. 85.

[13] Tardy 1971–72, vol. 1, p. 74; Augarde 1996, pp. 285, 287.

[14] Tardy 1971–72, vol. 1, pp. 240–41; Augarde 1996, pp. 317–18.

[15] Augarde 1996, pp. 317–18.

[16] Collection Double 1881, p. 86, no. 274.

[17] Parker in Dauterman, Parker, and Standen 1964, pp. 269, 272.

Artwork Details

- Title: Mantel clock with musical movement

- Maker: Clockmaker: Jean-Baptiste-André Furet (French, ca. 1720–1807)

- Date: ca. 1784

- Culture: French, Paris

- Medium: Case: gilded and lacquered bronze and marble; Movement (in bust): brass and steel with enameled hour and minute chapter rings (in head); Miniature organ with pipes and bellows (in base): brass, steel, and leather

- Dimensions: Overall: 29 × 16 1/4 × 9 in. (73.7 × 41.3 × 22.9 cm)

- Classification: Horology

- Credit Line: Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1958

- Object Number: 58.75.127

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.