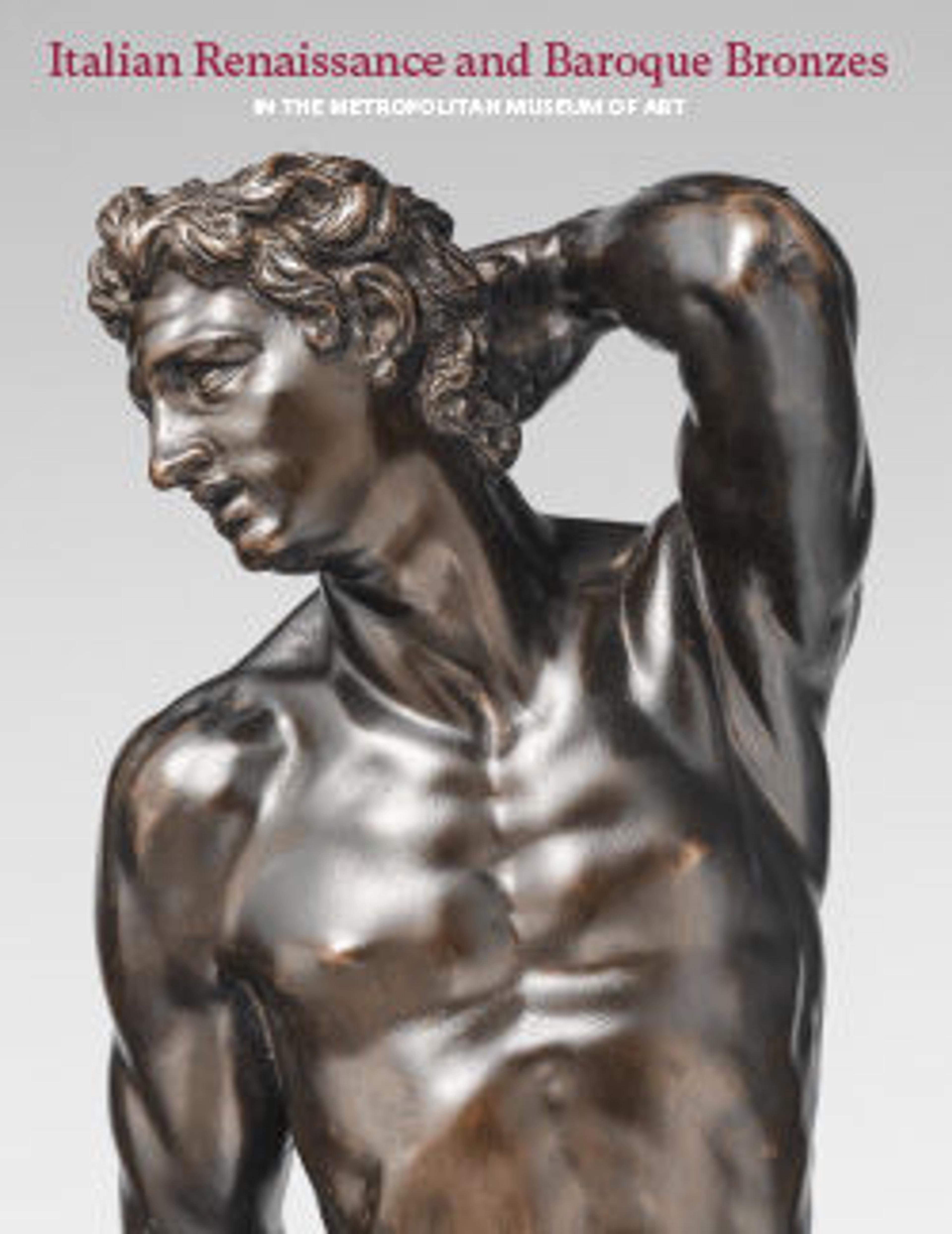

The suicide of Dido, Queen of Carthage

This bronze statuette depicts the suicide of Dido, queen of Carthage. According to Virgil’s Aeneid, when Dido failed to persuade her lover, the Trojan hero Aeneas, to remain with her, she plunged his sword into her breast as he sailed away. Here, a bit of drapery flutters around Dido’s nude body. The sword is missing. The subject was first interpreted as the Roman matron Lucretia, heroine of another classical tale of self-murder.[1] James David Draper, who pointed out that the figure wears a crown, provided the correct reading.[2] At least two other versions are known: one in London and a silvered cast in Munich.[3]

The Dido has been variously attributed to a follower of Bernini in Rome, possibly of Flemish origin, circa 1650;[4] a Netherlandish artist under the influence of Bernini;[5] a first-rate sculptor who “shows knowledge of the rhetorical language of Bernini and Rubens in equal measure” (noting similarities with François Duquesnoy’s Flagellation groups);[6] and Ferdinando Tacca, because of its kinship with the features and theatrical attitude of bronzes such as Roger and Angelica or Mercury and Juno.[7] Anthony Radcliffe, discussing the London version, argued that the group of bronze Didos “derive from an unknown original in ivory or boxwood.” He also considered plausible the ascription to a Roman-based Flemish artist and noted the Rubensian character of the form.[8]

Stylistically, a Flemish or Netherlandish origin seems to be more tenable, and this is corroborated by Richard Stone’s technical analysis of our Dido.[9] It was cast in brass with an armature of iron wire that is paired and twisted into spiral lengths, obviating the need for more typical core pins and plugs. The billowing drapery was cast separately and joined with solder. Interestingly, a statuette of Lucretia committing suicide recently appeared on the art market with a “South Netherlandish, circa 1700” designation.[10] Though not analogous to our bronze in general features, the Lucretia and the Dido might derive from two different castings of the same original series of Roman heroines.

-FL

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Untermyer 1962; Weihrauch 1967, pp. 489–90.

2. MMA 1975, p. 232.

3. V&A, A.113-1956 (Radcliffe 1966, p. 108, pl. 70); Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, 63/3 (Munich 1974, p. 62, no. 42 [as “Lukretia”]).

4. Untermyer 1962.

5. Weihrauch 1967, pp. 479–80.

6. Draper in Untermyer 1977, pp. 170–71.

7. Draper notes, April 1994, ESDA/OF.

8. Radcliffe 1966, p. 108, citing the Untermyer version as an “identical cast.”

9. R. Stone/TR, February 2011.

10. Sotheby’s, London, July 9, 2015, lot 107.

The Dido has been variously attributed to a follower of Bernini in Rome, possibly of Flemish origin, circa 1650;[4] a Netherlandish artist under the influence of Bernini;[5] a first-rate sculptor who “shows knowledge of the rhetorical language of Bernini and Rubens in equal measure” (noting similarities with François Duquesnoy’s Flagellation groups);[6] and Ferdinando Tacca, because of its kinship with the features and theatrical attitude of bronzes such as Roger and Angelica or Mercury and Juno.[7] Anthony Radcliffe, discussing the London version, argued that the group of bronze Didos “derive from an unknown original in ivory or boxwood.” He also considered plausible the ascription to a Roman-based Flemish artist and noted the Rubensian character of the form.[8]

Stylistically, a Flemish or Netherlandish origin seems to be more tenable, and this is corroborated by Richard Stone’s technical analysis of our Dido.[9] It was cast in brass with an armature of iron wire that is paired and twisted into spiral lengths, obviating the need for more typical core pins and plugs. The billowing drapery was cast separately and joined with solder. Interestingly, a statuette of Lucretia committing suicide recently appeared on the art market with a “South Netherlandish, circa 1700” designation.[10] Though not analogous to our bronze in general features, the Lucretia and the Dido might derive from two different castings of the same original series of Roman heroines.

-FL

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Untermyer 1962; Weihrauch 1967, pp. 489–90.

2. MMA 1975, p. 232.

3. V&A, A.113-1956 (Radcliffe 1966, p. 108, pl. 70); Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, 63/3 (Munich 1974, p. 62, no. 42 [as “Lukretia”]).

4. Untermyer 1962.

5. Weihrauch 1967, pp. 479–80.

6. Draper in Untermyer 1977, pp. 170–71.

7. Draper notes, April 1994, ESDA/OF.

8. Radcliffe 1966, p. 108, citing the Untermyer version as an “identical cast.”

9. R. Stone/TR, February 2011.

10. Sotheby’s, London, July 9, 2015, lot 107.

Artwork Details

- Title: The suicide of Dido, Queen of Carthage

- Artist: Ferdinando Tacca (Italian, Florence 1619–1686 Florence)

- Date: late 17th century

- Culture: Possibly Flanders

- Medium: Bronze, on later wood base

- Dimensions: Overall with base (confirmed): 13 × 4 3/4 × 4 3/4 in. (33 × 12.1 × 12.1 cm); overall without base (confirmed): 9 1/16 × 4 3/4 × 3 3/4 in. (23 × 12.1 × 9.5 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964

- Object Number: 64.101.1466

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.