Crossbow (Halbe Rüstung) with Cranequin (Winder)

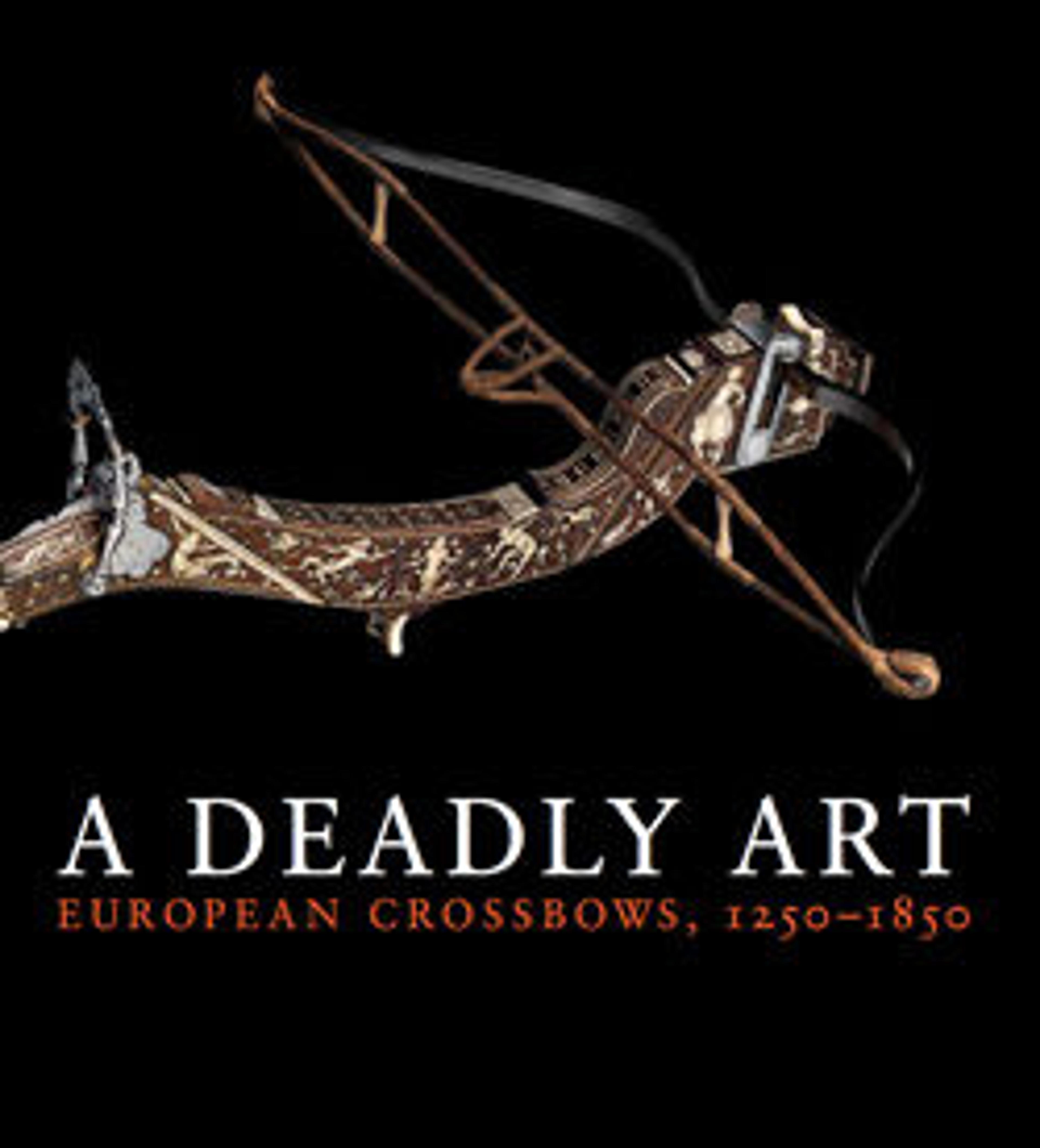

The straight walnut stock of this crossbow is inlaid with staghorn in an interlaced pattern of strapwork; upper and lower faces are veneered in staghorn engraved with masks and strapwork. Approximately in the middle of the stock is the nut––the pivoted bone cylinder with two cutouts, one for the string and one for the sear––and also a notch for the butt of the bolt. Directly to the rear of the nut is the folding peep sight, adjustable vertically and horizontally. Farther back is a transverse peg, which serves as the rest for the winder. A hand's breadth from the butt end is an inserted brass thumb rest. The release mechanism is double, a long lever and a hair trigger with three forward sears which can be set by inserting a peg through a set-hole in the stock. The folding hair trigger is under the lever.

Directly in front of the trigger is a safety swivel. The release nut is secured by eight strands of hemp thread bound around the stock. The steel bow is lashed to the forked forward end of the stock by heavy hemp cords, which also hold a suspension ring. Pompoms of green wool are attached to the bow as decoration (Aufputz).

Throughout the Middle Ages the crossbow was the most widely used missile weapon, through the English longbow has been much more popularized in modern romantic literature. Due to the extraordinary strength of its steel bow, the crossbow had superior penetration power and an accuracy barely surpassed by the modern rifle. It could have up to ten times the "pull" of a longbow, and therefore had to be spanned mechanically. As a consequence, its shooting speed was much slower than that of a longbow, but since both archers and crossbowmen carried only a limited supply of missiles––usually twenty-four arrows––into battle, shooting quickly might mean running out of ammunition too fast. Early crossbows had bows made of laminated horn or whalebone; steel bows were only introduced from the late fifteenth century onward, when technology was sufficiently advanced to produce good springy steel.

The crossbow was officially abolished as a military weapon in Germany in 1517 by order of Emperor Maximilian, though it was still used in other countries, as for instance Spain where Cortez and Pizarro armed their men with crossbows for the conquests of Mexico (1519–21) and Peru (1532–33). Though for military purposes firearms became more and more efficient, crossbows were prized as hunting weapons because of their silent release and the absence of a recoil. This explains the design of a straight crossbow stock, which was held lightly against the cheek and did not need to be braced against the shoulder.

The most practical spanner for heavy crossbows was the cranequin, consisting of a rack and reduction gear with handle. The gear box is usually almost circular, with a heavy loop of hemp rope attached to the underside. This loop would be slipped over the butt end of the crossbow stock and brought to rest against the transverse pegs to the rear of the release mechanism. The double claw of the rack, in extended position, would be slipped over the bow string, to be pulled back by turning the handle of the gears. The gear ratio of this winder is twelve to one.

Rack and gear housing are etched with floral scrolls and sea monsters; next to the claw is stamped the mark of the maker: a shield shape enclosing a purse surmounted by the initials I and K, inlaid in brass, and flanked by the date 1562.

Light crossbows with a "pull" of around 125 pounds could be spanned by setting them on the ground upside down. The crossbowman would squat down, place a claw-like hook attached to his belt behind the string and stand up until the string would rest into the nut (the thigh muscles are the strongest muscles in the human body, the arm muscles would not be able to exert the necessary pressure). Another way of spanning light crossbows was with a "goat's-foot lever," which had a long arm with a short fork hinged to it. The forward end of the arm was hooked into a ring at the fore-end of the stock, and the hinged fork set against the string. By pulling back the long arm the fork was made to move the string into the locking position. Oversize crossbows stationed on ramparts of castle walls were spanned with windlasses, using claws and pulleys. In the open field, however, this system was not practical, though it is still beloved by writers of historical novels who want to stress the differences between agile longbowmen and cumbersome crossbowmen.

Directly in front of the trigger is a safety swivel. The release nut is secured by eight strands of hemp thread bound around the stock. The steel bow is lashed to the forked forward end of the stock by heavy hemp cords, which also hold a suspension ring. Pompoms of green wool are attached to the bow as decoration (Aufputz).

Throughout the Middle Ages the crossbow was the most widely used missile weapon, through the English longbow has been much more popularized in modern romantic literature. Due to the extraordinary strength of its steel bow, the crossbow had superior penetration power and an accuracy barely surpassed by the modern rifle. It could have up to ten times the "pull" of a longbow, and therefore had to be spanned mechanically. As a consequence, its shooting speed was much slower than that of a longbow, but since both archers and crossbowmen carried only a limited supply of missiles––usually twenty-four arrows––into battle, shooting quickly might mean running out of ammunition too fast. Early crossbows had bows made of laminated horn or whalebone; steel bows were only introduced from the late fifteenth century onward, when technology was sufficiently advanced to produce good springy steel.

The crossbow was officially abolished as a military weapon in Germany in 1517 by order of Emperor Maximilian, though it was still used in other countries, as for instance Spain where Cortez and Pizarro armed their men with crossbows for the conquests of Mexico (1519–21) and Peru (1532–33). Though for military purposes firearms became more and more efficient, crossbows were prized as hunting weapons because of their silent release and the absence of a recoil. This explains the design of a straight crossbow stock, which was held lightly against the cheek and did not need to be braced against the shoulder.

The most practical spanner for heavy crossbows was the cranequin, consisting of a rack and reduction gear with handle. The gear box is usually almost circular, with a heavy loop of hemp rope attached to the underside. This loop would be slipped over the butt end of the crossbow stock and brought to rest against the transverse pegs to the rear of the release mechanism. The double claw of the rack, in extended position, would be slipped over the bow string, to be pulled back by turning the handle of the gears. The gear ratio of this winder is twelve to one.

Rack and gear housing are etched with floral scrolls and sea monsters; next to the claw is stamped the mark of the maker: a shield shape enclosing a purse surmounted by the initials I and K, inlaid in brass, and flanked by the date 1562.

Light crossbows with a "pull" of around 125 pounds could be spanned by setting them on the ground upside down. The crossbowman would squat down, place a claw-like hook attached to his belt behind the string and stand up until the string would rest into the nut (the thigh muscles are the strongest muscles in the human body, the arm muscles would not be able to exert the necessary pressure). Another way of spanning light crossbows was with a "goat's-foot lever," which had a long arm with a short fork hinged to it. The forward end of the arm was hooked into a ring at the fore-end of the stock, and the hinged fork set against the string. By pulling back the long arm the fork was made to move the string into the locking position. Oversize crossbows stationed on ramparts of castle walls were spanned with windlasses, using claws and pulleys. In the open field, however, this system was not practical, though it is still beloved by writers of historical novels who want to stress the differences between agile longbowmen and cumbersome crossbowmen.

Artwork Details

- Title: Crossbow (Halbe Rüstung) with Cranequin (Winder)

- Date: crossbow, ca. 1575–1650; cranequin dated 1562

- Geography: possibly Saxony

- Culture: probably German, possibly Saxony; cranequin, probably German

- Medium: Steel, wood (fruitwood, probably cherry and plum), staghorn, copper alloy, hemp, wool

- Dimensions: crossbow, L. 24 3/16 in. (63 cm); W. 23 7/16 in. (59.5 cm); Wt. 8 lb. 7 oz. (3,775 g); cranequin, L. 13 3/4 in. (34.8 cm); W. 4 1/8 in. (10.4 cm); Wt. 5 lb. 11 oz. (2,567 g).

- Classification: Archery Equipment-Crossbows

- Credit Line: Gift of William H. Riggs, 1913

- Object Number: 14.25.1574a, b

- Curatorial Department: Arms and Armor

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.