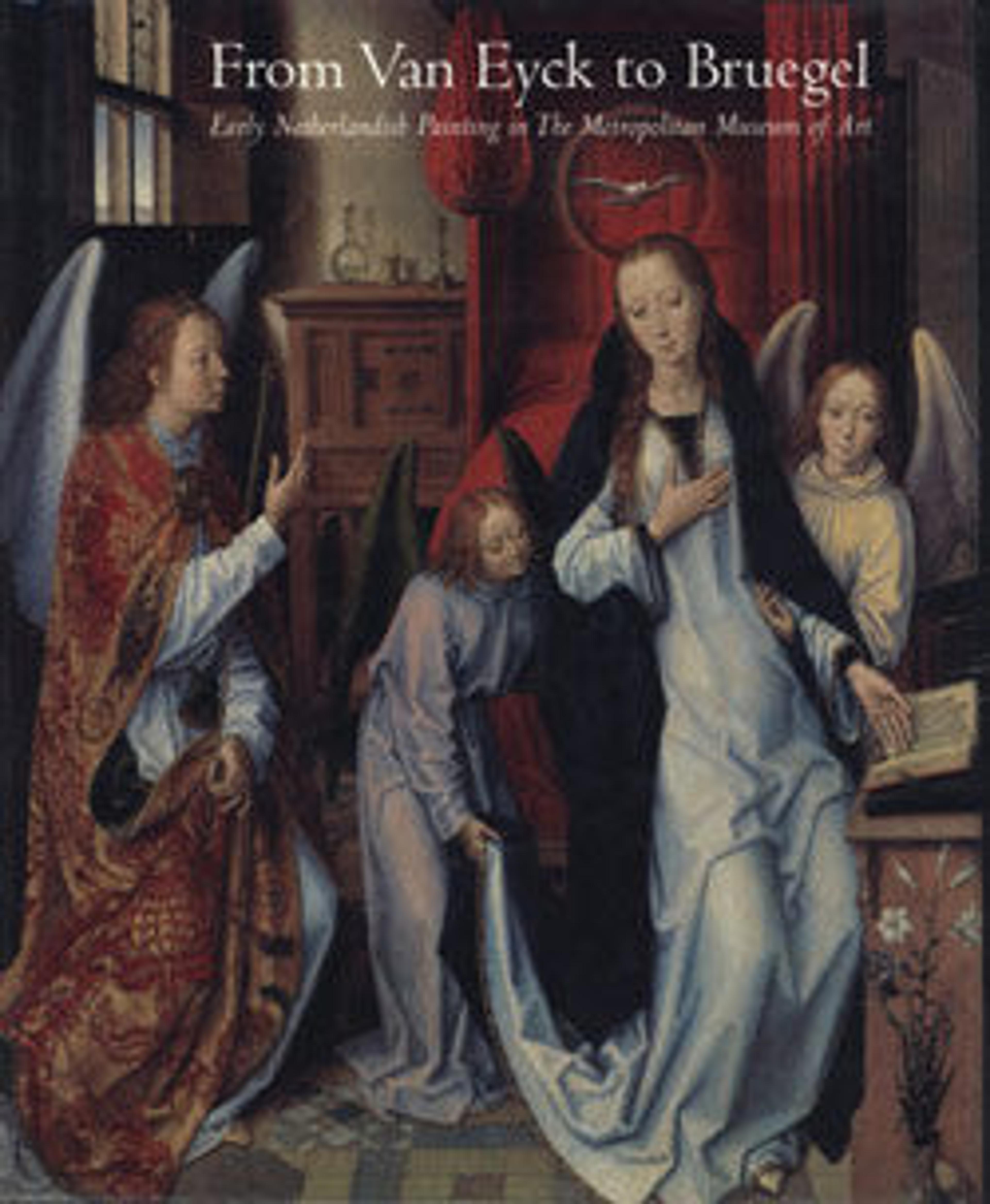

Saint Paul with a Donor; Christ Appearing to His Mother

The mysterious artist known to modern scholars as the Master of the Legend of Saint Ursula (after a celebrated series of paintings) seems to have headed an active workshop in Bruges. In the left panel, a donor is portrayed with his patron saint, Paul, whose beheading is shown through an open arch in a city square. In the right panel, Mary and Mary Magdalen appear in the distance, approaching the still-sealed tomb of Christ, while the foreground scene depicts a moment after the Resurrection, when Christ appears to his mother.

Artwork Details

- Title: Saint Paul with a Donor; Christ Appearing to His Mother

- Artist: Master of the Saint Ursula Legend (Netherlandish, active late 15th century)

- Date: ca. 1485

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: (a) overall 37 3/8 x 11 3/8 in. (94.9 x 28.9 cm), painted surface 36 3/4 x 10 7/8 in. (93.4 x 27.6 cm); (b) overall 37 1/4 x 11 1/4 in. (94.6 x 28.6 cm), painted surface 36 3/4 x 10 3/4 in. (93.4 x 27.3 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931

- Object Number: 32.100.63ab

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.