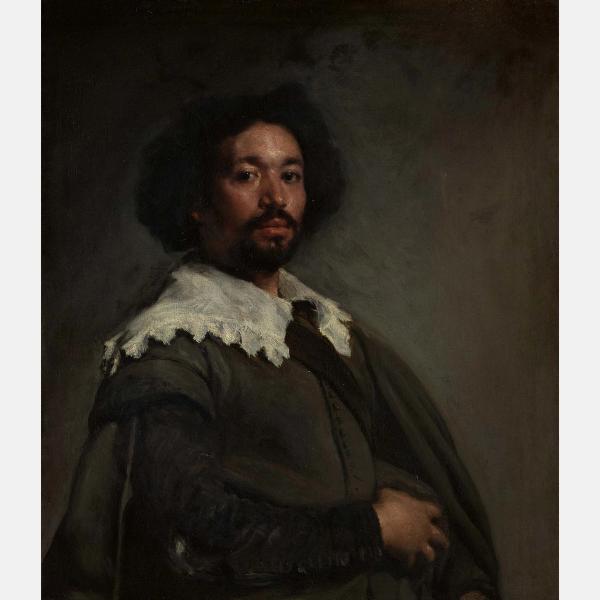

Juan de Pareja (ca. 1608–1670)

Between 1649 and 1651, Velázquez traveled to Italy with Juan de Pareja, a man of African descent born in southern Spain who was enslaved in Velázquez’s studio and household for at least two decades. According to an early biography, shortly after arriving in Rome, Velázquez exhibited this portrait, "which was so like him and so lively that, when he sent it by means of Pareja himself to some friends for their criticism, they just stood looking at the portrait in admiration and wonder, not knowing to whom they should speak or who would answer." Within months of completing it, Velázquez signed papers that would liberate Pareja by 1654, paving the way for his own successful career as a painter in Madrid. Enslaved artisanal labor was widespread in the workshops of Spanish painters, sculptors, silversmiths and woodworkers at this time.

Artwork Details

- Title: Juan de Pareja (ca. 1608–1670)

- Artist: Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid)

- Date: 1650

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 32 x 27 1/2 in. (81.3 x 69.9 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876-1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971

- Object Number: 1971.86

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

637. Juan de Pareja, Diego Velázquez, 1650

STEPHANIE ARCHANGEL: Juan de Pareja’s portrait by Velázquez is an extremely important painting because there’s so many questions to be asked.

My name is Stephanie Archangel and I’m a curator at the history department of the Rijksmuseum.

It starts with his identity. Is he white? Is he black? And almost kind of forget that he’s a marvelous painter himself who was enslaved at that point in time and is freed by his enslaver who’s one of the biggest artists of all time and then you have the question of how and why was he freed?

NARRATOR: And then there is the gravity and intensity of the image itself.

STEPHANIE ARCHANGEL: He’s fiercely looking at you. He’s really making his presence felt instead of shying away from the viewer which, if you look at paintings from the 17th century where Black people were portrayed mostly looking down or up towards the white sitter or mostly looking away, but not having this one-on-one connection with you as you are standing in front of it. For a person enslaved in that period of time, it’s almost unbelievable that he takes this kind of stance.

NARRATOR: It’s likely that the reception of this painting exhibited at the Pantheon in Rome brought Pareja a certain level of renown. Even though it was mutually beneficial to the painter and subject, we must acknowledge and question the relationship between enslaver and enslaved.

STEPHANIE ARCHANGEL: I don’t know quite where the agency is, and I think that’s the interesting thing about this painting because you don’t know. But you keep asking that question. And I don’t think we will ever get an answer to that. Or a satisfying answer to that.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.