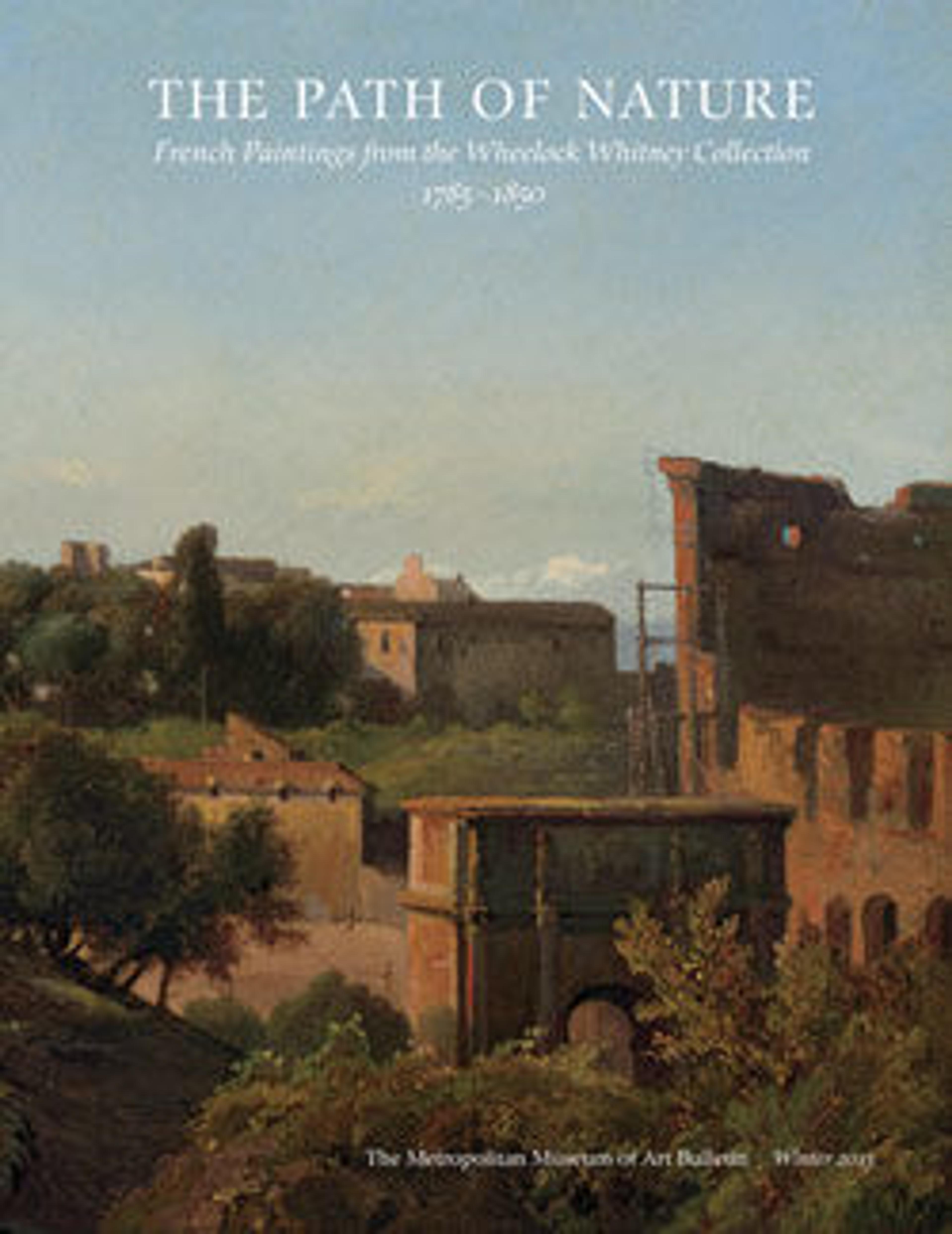

The Palazzo Reale and the Harbor, Naples

This sketch was painted between 1810 and 1815, during Dunouy’s second Italian sojourn. It served as a study for View of the Palazzo Reale from Santa Lucia, which belonged to Napoleon’s sister Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples (it is now in the Palazzo Reale). Dunouy’s views of Naples were as highly prized by Grand Tourists as they were by the royal patrons whose support enhanced his success.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Palazzo Reale and the Harbor, Naples

- Artist: Alexandre Hyacinthe Dunouy (French, Paris 1757–1841 Jouy-en-Josas)

- Date: ca. 1810–15

- Medium: Oil on paper, laid down on canvas

- Dimensions: 8 3/8 x 11 1/2 in. (21.2 x 29.2 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Whitney Collection, Promised Gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and Purchase, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003

- Object Number: 2003.42.25

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.