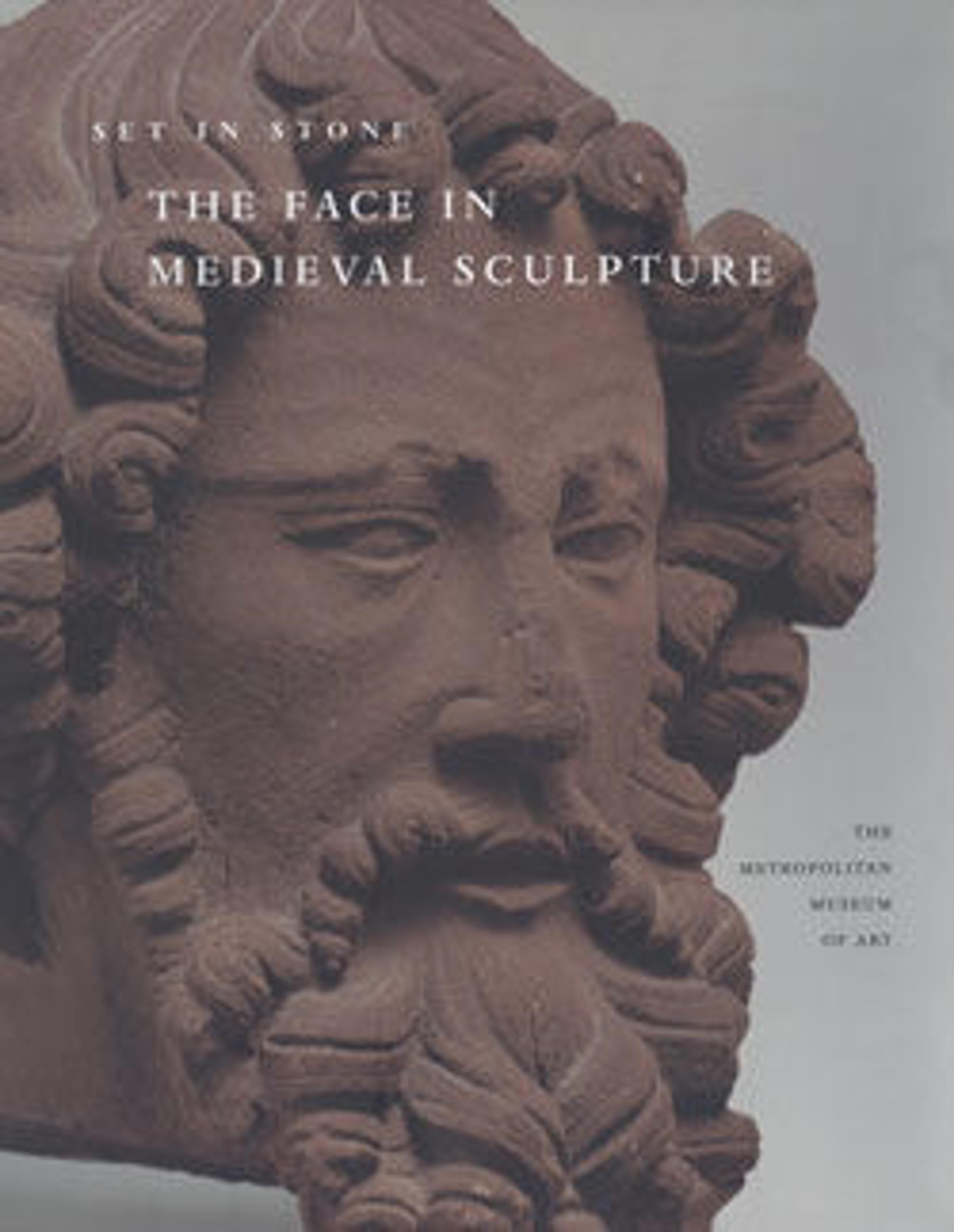

Reliquary Bust of Saint Balbina

Medieval reliquaries often took the form of the body parts they were created to contain. Bust reliquaries for the skulls of saints were placed on or near altars and, by the late Middle Ages, were assembled in large numbers in some church sanctuaries, from Cologne in the north to Ubeda in southern Spain. These examples, with elaborate jewels, beautifully braided hair, and richly decorated gowns, probably represent companions of the virgin martyr Saint Ursula, believed to have been eleven thousand in number. The small glazed medallions resembling jewelry once displayed additional relics. On particular feast days, such busts could be carried in processions.

Artwork Details

- Title: Reliquary Bust of Saint Balbina

- Date: ca. 1520–30

- Geography: Made in possibly Brussels, Belgium

- Culture: South Netherlandish

- Medium: Oak, with paint and gilding, and human remains

- Dimensions: Overall: 17 1/2 x 16 x 6 1/4 in. (44.5 x 40.6 x 15.9 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Wood

- Credit Line: Bequest of Susan Vanderpoel Clark, 1967

- Object Number: 67.155.23

- Curatorial Department: Medieval Art and The Cloisters

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.