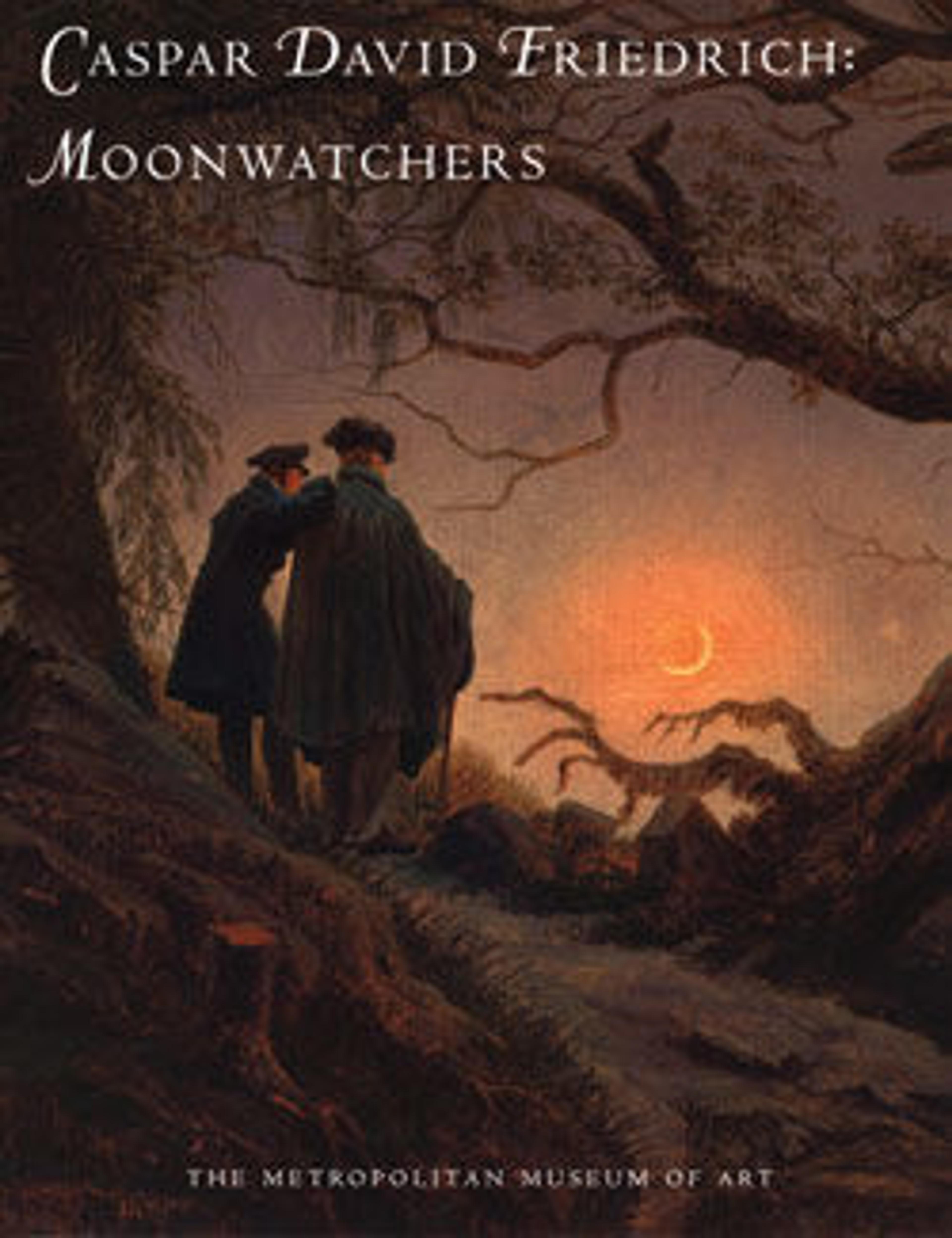

Caspar David Friedrich: Moonwatchers

56 pages

45 illustrations

This title is out of print.

Director's Foreword

Acknowledgments

Note to the Reader

Moonwatchers

Sabine Rewald

Friedrich and Two Danish Moonwatchers

Kasper Monrad

Catalogue

Sabine Rewald

Selected Bibliography

Met Art in Publication

Jan van Eyck

ca. 1436–38

Multiple artists/makers

n.d.

Caspar David Friedrich

ca. 1825–30

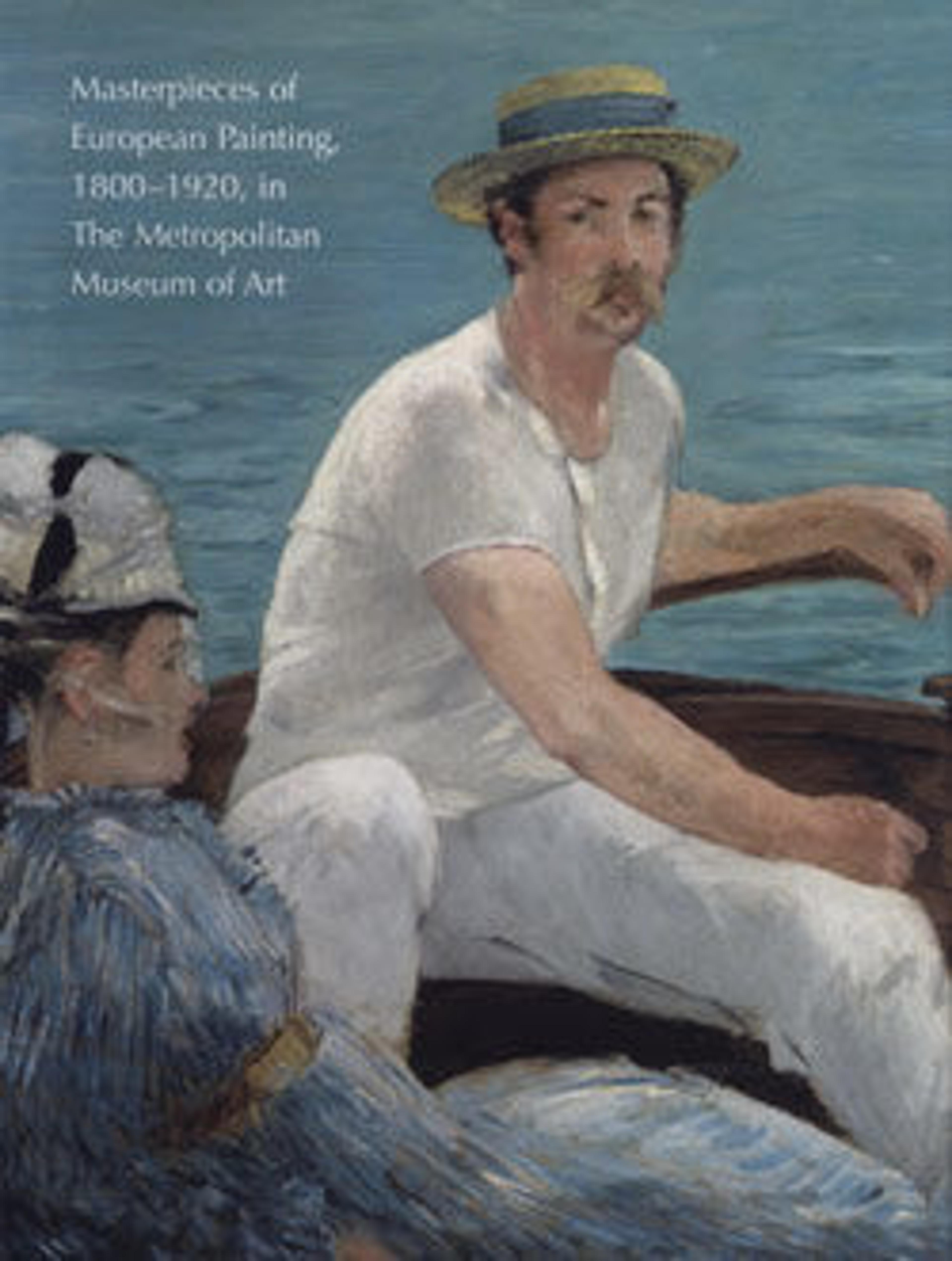

You May Also Like

A slider containing 5 items.

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Citation

Rewald, Sabine, and Kasper Monrad. 2001. Caspar David Friedrich: Moonwatchers. New York : [New Haven, Conn.]: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press.