David Hockney (English, born 1937). Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, 1968. Acrylic on canvas, 212 x 303.5 cm. Private collection. © David Hockney

In the center gallery of the exhibition David Hockney—on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through February 25—is a stunning selection of six double portraits, a modern paean to the art of figurative painting. Among those represented in these pictures, which include the artist's parents, the art-world star (and former Met curator) Henry Geldzahler and his boyfriend Christopher Scott, and Hockney's dear friends Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell, is the famed English writer Christopher Isherwood and his partner, the American visual artist Don Bachardy. Painted in 1968, the Isherwood-Bachardy double portrait is the first of this form Hockney completed, and shows the couple seated in the Santa Monica, California, home they were to share for decades. While the painting's composition would become a seminal perspective for Hockney—a triangulation among the two subjects and the viewer, with one figure facing front while the other is presented in stark profile—the portrait's subjects represent a new dimension to the unapologetic homosensuality that pervades Hockney's work: the couple depicted here were just as unapologetic in the honesty and openness of their gay relationship, a daring feat in conservative mid-century America.

The pair met in 1952 in Malibu (on a beach that could be seen from the living room of the couple's home) when Isherwood was 48 years old and Bachardy just 18. But despite the 30-year age difference, theirs was a true partnership—professional, emotional, and sexual—that endured until Isherwood's death from cancer in 1986. Hockney's 1968 portrait presents the pair at a volatile time in Western society's slow progression toward same-sex equality, sandwiched between the decriminalization of homosexual acts in England and Wales in 1967 and the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York City's Greenwich Village, which is largely considered to be the beginning of the gay-rights movement in the United States. Isherwood and Bachardy were also moving through a period of personal turmoil and change; the pressure of each artist's work and career, their wandering eyes for other sexual partners while apart, and the hostility faced by gay couples in mid-century America weighed heavily on both men, who came perilously close to ending their relationship around the time of Hockney's painting.

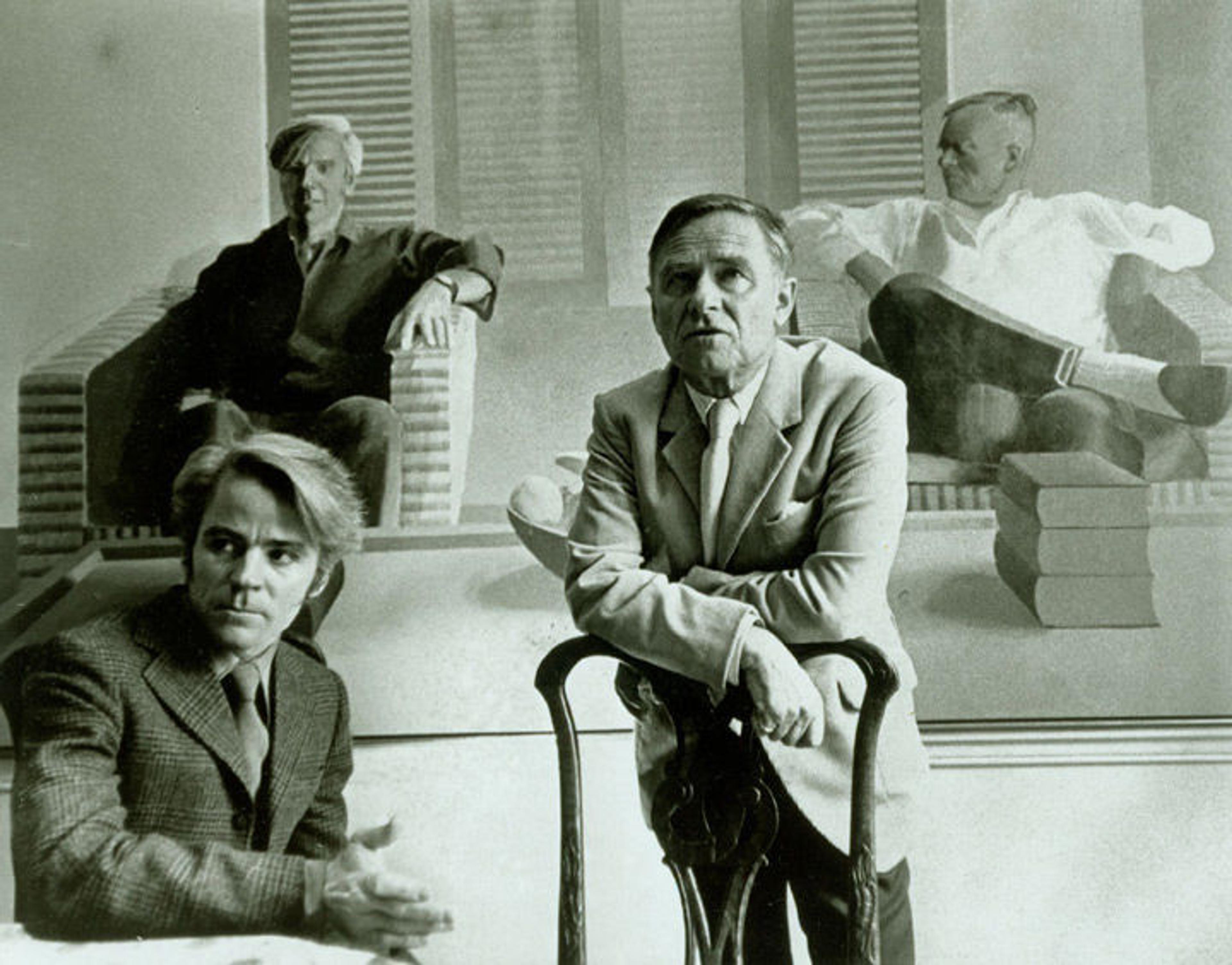

Isherwood and Bachardy in front of Hockney's portrait. Photo by Calvin Brodie

The letters that Isherwood and Bachardy frequently exchanged throughout most of their relationship, from their first time apart in 1956 to the early 1970s, provide deeply intimate insights into the couple's lives at a time of great hostility toward sexual minorities. Published in 2014, The Animals: Love Letters between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy—masterfully compiled and edited by Katherine Bucknell, director of the Christopher Isherwood Foundation and the editor of four volumes of the writer's diaries—showcases the couple's deep adoration for each other (the titular "animals" are Dobbin, a stubborn workhorse that represented Isherwood, and Kitty, a playful feline persona they used for Bachardy) as well as their difficulties confronting what it meant to be in a public relationship and how exactly to survive the great distances and time they had to spend apart. (Bachardy often traveled to Europe for work and exhibited in New York, while Isherwood largely stayed in southern California.)

Although a seemingly light-hearted character device, Isherwood spoke directly of Dobbin and Kitty's roles in their letters—and their relationship—in a letter dated March 11, 1963, stating: "I often feel that the Animals are far more than just a nursery joke or a cuteness. They exist. They are like Jung's myths. They express a kind of freedom and truth which we otherwise wouldn't have."[1] Freedom and truth were certainly not easy currencies for two gay men to acquire in 1960s America, further amplifying the importance of the couple's imaginary animal personae.

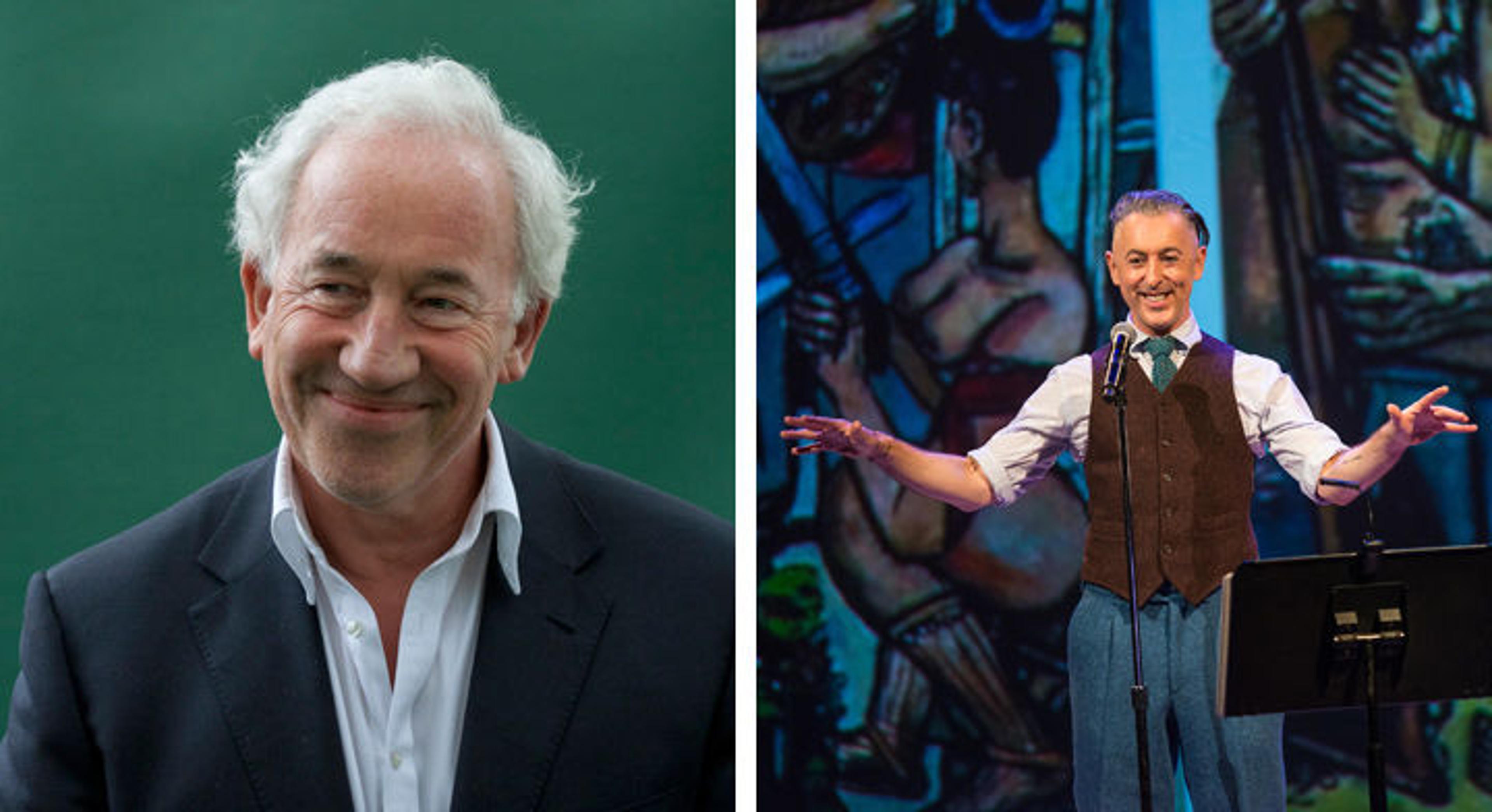

In celebration of this relationship and the major retrospective of David Hockney's work, MetLiveArts will present an evening-length reading of The Animals on Tuesday, February 13, in the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium. Featuring acclaimed stage and screen actors Simon Callow (as Isherwood) and Alan Cumming (as Bachardy)—who also read these letters in Bucknell's incredible 11-episode podcast of the same name—this event will pay tribute to the literary testament left behind by these two extraordinary men, who dared to live their lives as openly as possible at a time of great intolerance and homophobia.

Ahead of the performance next week, I had the chance to speak with Callow and Cumming about their history with Isherwood and Bachardy's letters, the characterization they bring to their reading of these emotionally complicated texts, and their thoughts on Hockney's iconic portrait.

Left: Simon Callow. Photo courtesy of the artist. Right: Alan Cumming. Photo by Stephanie Berger

Michael Cirigliano: Considering that Isherwood and Bachardy's letters are explicit declarations of love and devotion at a time when homosexuality was largely criminalized, what sort of impact did they have on you when you first encountered them?

Simon Callow: I didn't come across the letters until they were published in 2014; I don't think anyone other than Isherwood scholars had. They were a delight to read, but by that point there was nothing sensational or bold or controversial about the expressions of affection or the sexual references; in fact, Christopher's diaries were much more explicit and forthright. Letters have never been censored, except from the war front or from prison, so they tend to be pretty frank. What is quite remarkable about these particular letters is the life that they record, and how absolutely fearlessly and frankly the famous middle-aged writer and his younger boyfriend had lived their lives, in plain view of a hostile world.

Alan Cumming: I suppose my first experience of the letters was watching the documentary Chris and Don: A Love Story. I was really taken with just what an intense and intimate relationship theirs was. It's strange to think that writing a letter to your partner could be seen as an illegal act. We have come so far in terms of equality, and in some ways take so much for granted, but realizing this relationship—this beautiful, loving, and frank relationship—was in fact illegal, reminds me of how precarious our position is today, and the way that rights are being stripped away and everything about liberty and equality is under threat.

Michael Cirigliano: I was often amazed while reading the letters that Isherwood's potent lyricism was effortlessly at play even in this format. Do you have a particular favorite passage?

Simon Callow: The passage quoted in the Los Angeles Times review of the book is a pretty good example of Isherwood at his graphic best:

The fire burned on all through Wednesday; yesterday it was all over, though of course it can spring up again from embers, if there is another wind. Now it is beautiful, not too hot weather. From our windows, you could see the bombers dumping borate on the hills to put the fire out. One of them was nearly licked up by a huge flame which swept up at it as it dove.[2]

Alan Cumming: To be honest, I am actually more fascinated by the bits when they were lying to each other—Don especially. I find it really interesting to note subtle changes in his demeanor when he is obviously covering up some assignation. It's so hard to remember how travel arrangements and phones calls and telegrams were so laborious and complicated to negotiate. But it was easier to disappear, to hide.

Michael Cirigliano: How did you approach characterization as you were recording the podcast, and are there any differences in interpretation you'll make for a staged reading? Are you letting the words speak for themselves, or will there be a level of "acting" layered on top?

Alan Cumming: I had met Don a few times over the years because of my connection with Cabaret. A couple of years ago, just before I did the podcast, I went to his house in Santa Monica and he painted me. So, I had some idea of his voice and his demeanor, and I tried to infuse the letters with that knowledge. I wouldn't say I'm doing an impersonation, but perhaps an impression.

The striking thing to me is how similar the two men grew throughout their lives. Michelle Williams told me that when she talked to Don for research purposes before we started the Cabaret revival in 2014, she asked him if he missed Chris, and he replied: "Why would I miss him? I've become him."

Simon Callow: I once had a telephone conversation with Isherwood, just before he died, and the sound of his voice is still fresh in my ears. I've tried to be as accurate as I can. Very often with actors, the moment of breakthrough is when one finds the character's voice; with a living person this is often a question of getting the tone as much as the vowels and consonants, and then allowing oneself to become at ease with it. After all, acting is simply thinking another person's thoughts; finding the voice is the gateway to that.

Michael Cirigliano: It's been incredible to have Hockney's iconic double portrait on view here at The Met as part of the retrospective. As we move through a social climate that accepts queer identity in fits and starts—two steps forward, one step back—I've been able to see this painting as a gauge that monitors how far we as a community have come in being able to be out and proud of ourselves and our relationships. What do you meditate on as you view the portrait?

Alan Cumming: I think of the circles these men moved in—the international showbiz literati that huddled together and was ultimately so influential in our culture.

And then there are the layers of artifice that surround any relationship. Chris fascinated me because there are such different interpretations of the same events in his writing throughout the years. Goodbye to Berlin and Mr. Norris Changes Trains are the sanitized version of his years in Germany, and then his memoir Christopher and His Kind is the more frank and real account of that time, yet he had to talk about himself in the third person in that book. His letters are the most honest and human version, and we are lucky that he and Don let them be seen.

Simon Callow: When David first painted it, he and Christopher were beacons as gay men who were comfortably and unapologetically out at a time when that was very uncommon. It was the apparent effortlessness of it that made it so striking: their relationship was no big deal, they seemed to be saying. So this wonderful double portrait of a gay couple was, in its cool and unaggressive way, an affirmation of the normality of homosexuality, which was somehow even more radical than the already gathering voices of the militants. In a sense, Hockney and Isherwood and Bachardy were saying: "Some people are gay. Get over it." Like its 18th-century models, the portrait celebrates the quotidian: being gay doesn't have to be a drama.

Notes

[1] The Animals: Love Letters between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, ed. Katherine Bucknell (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014).

[2] Ibid.

To purchase tickets to "The Animals: Love Letters Between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy" or any other upcoming MetLiveArts event, visit www.metmuseum.org/tickets; call 212-570-3949; or stop by the Great Hall Box Office, open Monday–Saturday, 10:30 am–3:30 pm.