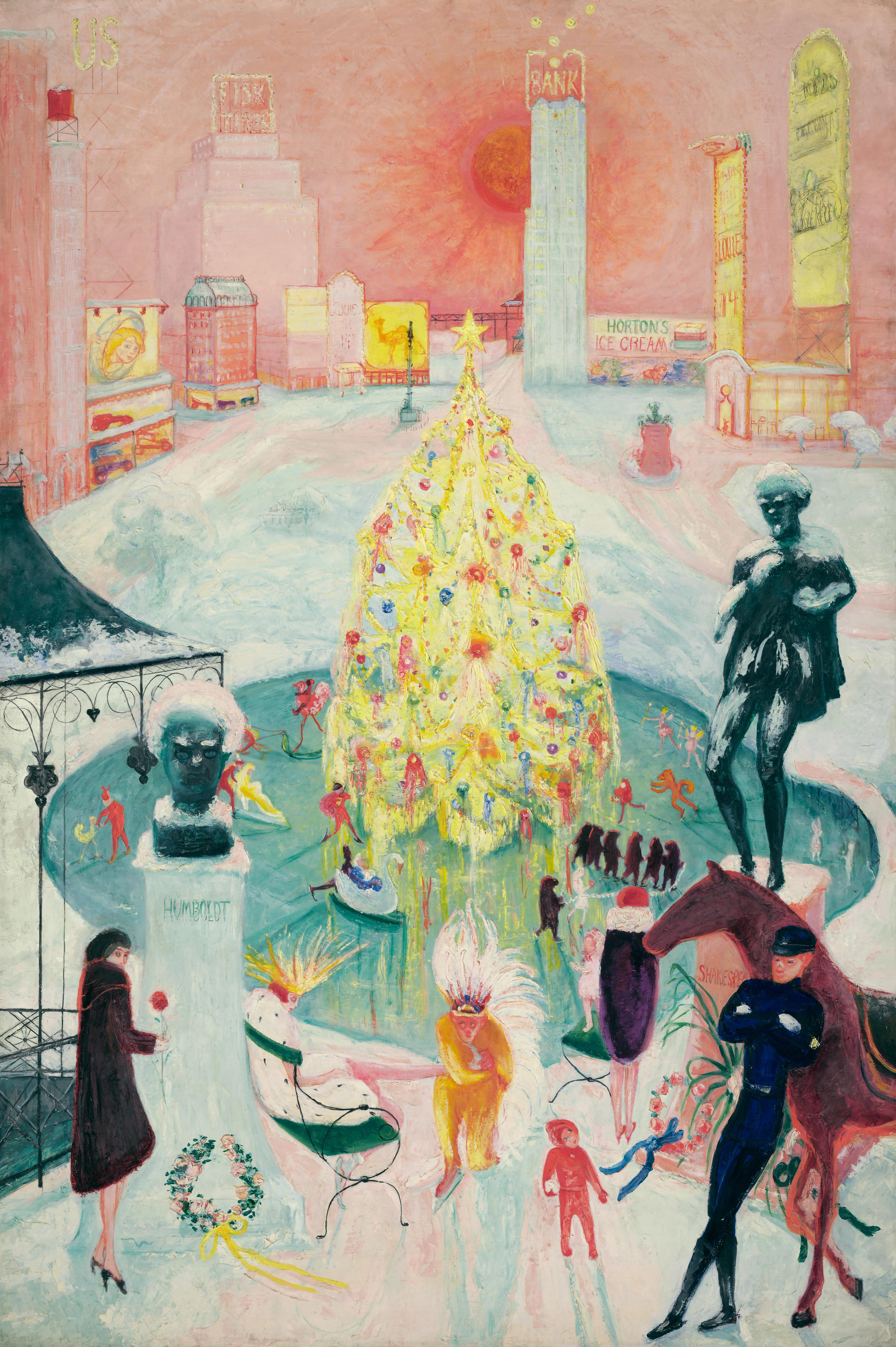

I saw my first Florine Stettheimer painting in November 2002 while working behind the jewelry counter at the Yale University Art Gallery gift shop. Across from me, on the lobby wall, was a painting of a huge, lemon-yellow Christmas tree on a teal ice-skating rink, flanked by white snow, tall pink buildings, and an orange-red sun aloft in a cotton-candy pink sky. There is not a single green needle on the artist’s Christmas tree, only draping swathes of pale-yellow garland and twinkly baubles in the shape of a tree. Stettheimer rendered the Christmas tree as a purely decorative object, and from that point on, she became a creative hero to me. Later, I discovered that within the sumptuous spaces the artist created in her paintings, she carved out room to represent her network of queer friends.

Florine Stettheimer (American, 1871–1944). Christmas, 1930–40. Oil on canvas, 60 1/8 × 40 in. (152.6 × 101.6 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer

Stettheimer’s interest in the decorative and her unique way of emphasizing it within painting was something she practiced across many aspects of her life. It was a yearly tradition on her birthday to make a flower arrangement, and her preference was to remove all the leaves and greenery from the flowers, leaving only the stems and blossoms, which curved like snakes being charmed from a basket. She would then paint them, calling them “eyegays,” alluding to the term nosegay, which refers to small bouquets of fragrant flowers worn or held close to the body. Stettheimer’s eyegays indulged sensory pleasure over narrative or accuracy.

Stettheimer had many close gay and lesbian friends in her creative circle who lived openly, and she painted them as they were, often making them the sole subjects of her paintings. These publicly shown portraits demonstrated the intimacy and respect she felt towards her queer friends. Her allyship challenged contemporary stigmas surrounding sexuality, and she also worked as a female artist in the early twentieth century, dedicating herself to her craft and career above all else, when institutions often underrepresented women in the arts.

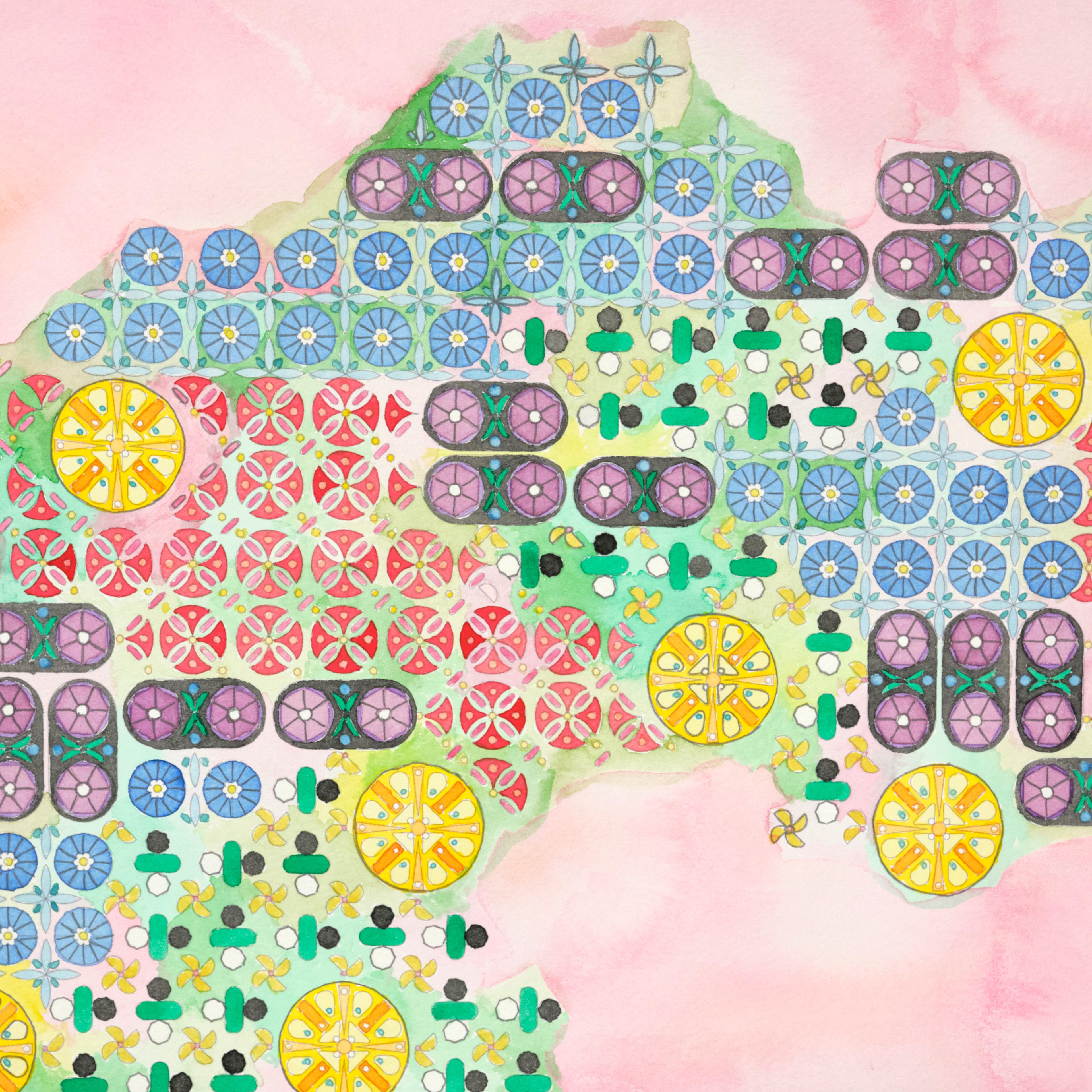

Chris Bogia (American, b. 1977). An Eyegay for Florine, 2025. Watercolor, pigment, and pencil on paper, 42 × 31 in. (106.7 × 78.7 cm) (CB_158). Photo by Jacob Holler. Courtesy of the artist and Mrs., Queens, NY

In response to Stettheimer’s deeply resonating aesthetic and queer themes, I produced a watercolor painting titled An Eyegay for Florine (2025) to celebrate both the artist and Pride Month. When considering Stettheimer, I discussed her with other queer artist friends, and we all wondered why we hadn’t been taught about her in school, especially since her formal sensibility inspired our artistic practices so much. Is Florine Stettheimer the Judy Garland of contemporary art, striking some kind of gay fancy? Are my friends and I engaging in art diva worship? Possibly. Do her paintings hit us in the face like the waving fringe on a Bob Mackie gown worn by Cher on a 1970s variety show we saw as toddlers? For sure. Is that lemon-yellow tree the great-grandmother to 2024’s brat green? Maybe.

Florine Stettheimer (American, 1871–1944). The Cathedrals of Art, 1942. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 × 50 1/4 in. (153 × 127.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ettie Stettheimer, 1953 (53.24.1)

While Stettheimer employed various colors, her signature hue was pink, present throughout the majority of her work, epitomized in The Cathedrals of Art (1942). Part of The Met’s Modern and Contemporary collection, it is one of four paintings in a series that Stettheimer worked on between 1929 and 1942. Looking at Stettheimer's vision of New York, I see an art world rendered like a gold-flecked bowl of strawberries and cream, celebrating the new and pulsating with activity. There are a pair of phallic columns in pastel pink, a central staircase in luminous fuchsia, and a rosy baby is under pink-tinged light from a pair of photographer’s flashbulbs. Off to the side, as usual, is Florine, whose white dress adorned with a bright pink flower is yet another visually generous detail among a sea of things I could mention.

Chris Bogia (American, b. 1977). An Eyegay for Florine (detail), 2025. Watercolor, pigment, and pencil on paper, 42 × 31 in. (106.7 × 78.7 cm) (CB_158). Photo by Jacob Holler. Courtesy of the artist and Mrs., Queens, NY

In my work An Eyegay for Florine, a hazy cloud of pink, inspired by Stettheimer's painting, dominates the background. In the foreground, a black vase sits on a blue Grecian pedestal, something I imagined in a corner of one of Stettheimer’s dwellings. The bouquet is informed by my interest in geometric abstraction and appliqué embellishments from fashion, suitably decorative for Florine Stettheimer. Prioritizing visual splendor was a crucial formal through-line throughout her career, as well as mine. I took a cue from the artist and avoided greenery. You may also notice, off to the right, a small white butterfly flutters in the pink sky—an ornament, an offering, and a symbol of the artist I want to celebrate.