Fig. 1. Roundel with a mounted falconer and hare, 12th–13th century, with early 20th-century additions. Iran. Islamic. Gypsum plaster; modeled, painted, and gilded; Diam. 7 1/2 in. (19 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1937 (37.55)

«Transformed: Medieval Syrian and Iranian Art in the Early 20th Century includes an intriguing stucco roundel, purchased by The Met in 1937, that various scholars have ascribed to the Seljuq period (fig. 1). This roundel, which has no known archaeological context, depicts a mounted falconer holding a bird of prey on his left hand while riding over a hare seeking to escape on the ground. Reassembled from several fragments with modern plaster fills along the join lines, this relief may have originally served as an architectural element in a secular building similar to a comparable piece now on view in the exhibition Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. Since the latter relief also lacks an archaeological provenance, however, their intended uses must remain speculative.»

Although no color remains on the high points of the relief, one can readily see traces of blue and red pigments in the recesses of the coarse-grained gypsum plaster surface along with a golden powder that appears to have been the first paint layer used on the headdress, the horse's tack, and the falconer's sleeve.

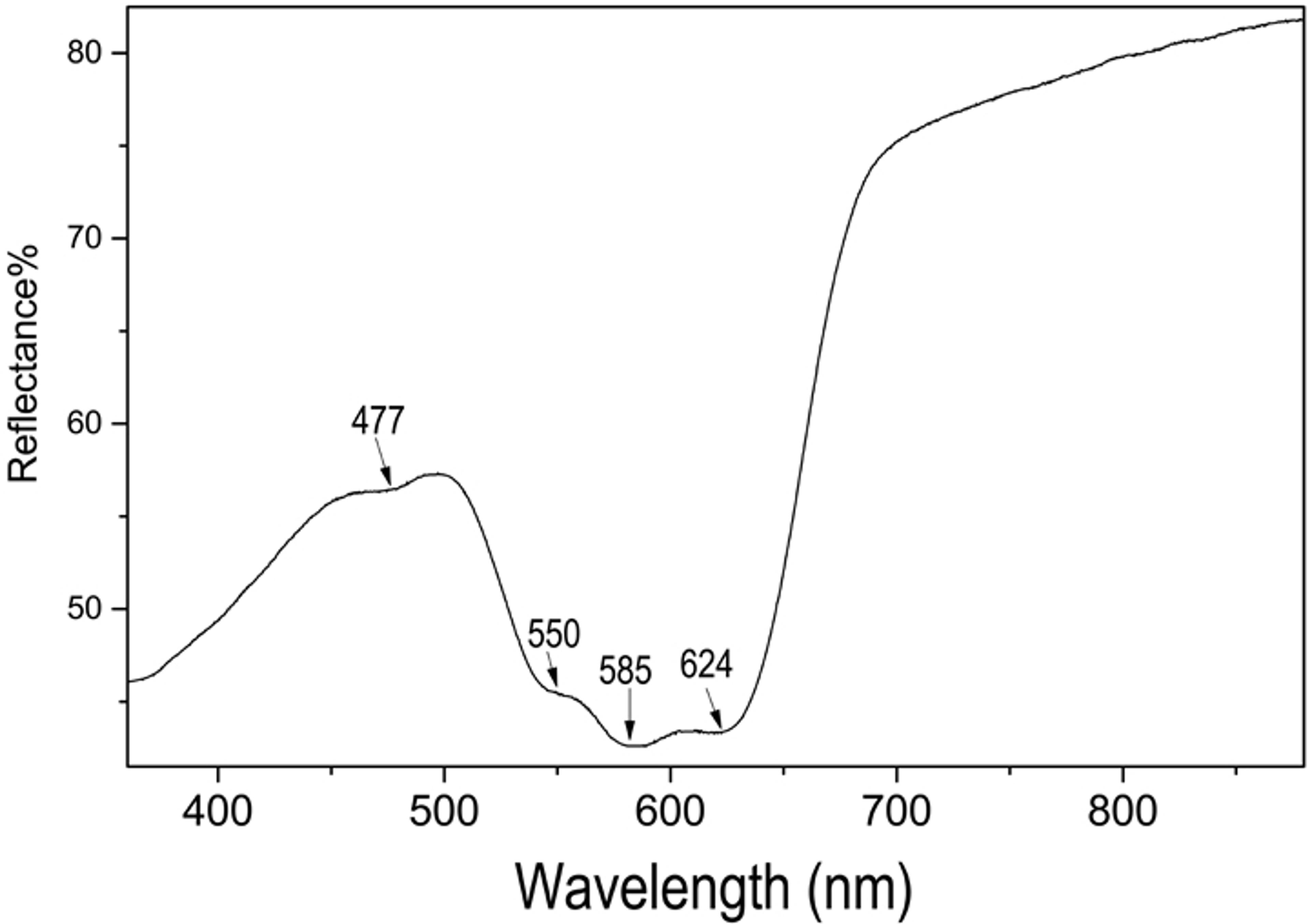

Optical reflectance spectra of the pigments indicated the use of more than one type of red pigment. Further in-depth and non-invasive microanalysis with X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) and micro-Raman spectroscopy identified hematite (α-Fe2O3) and vermilion (HgS) as the two red pigments. In addition, fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS) distinguished two different shades of blue, one of which exhibited the characteristic absorbance bands of cobalt blue, CoAl2O4 (fig. 2). This blue pigment was found only on the space between the heads of the falconer and the horse, an identification further confirmed by XRF, which identified cobalt and aluminum as two major elements within this pigment.

Fig. 2. Optical reflectance spectrum with characteristic absorbance bands of cobalt blue

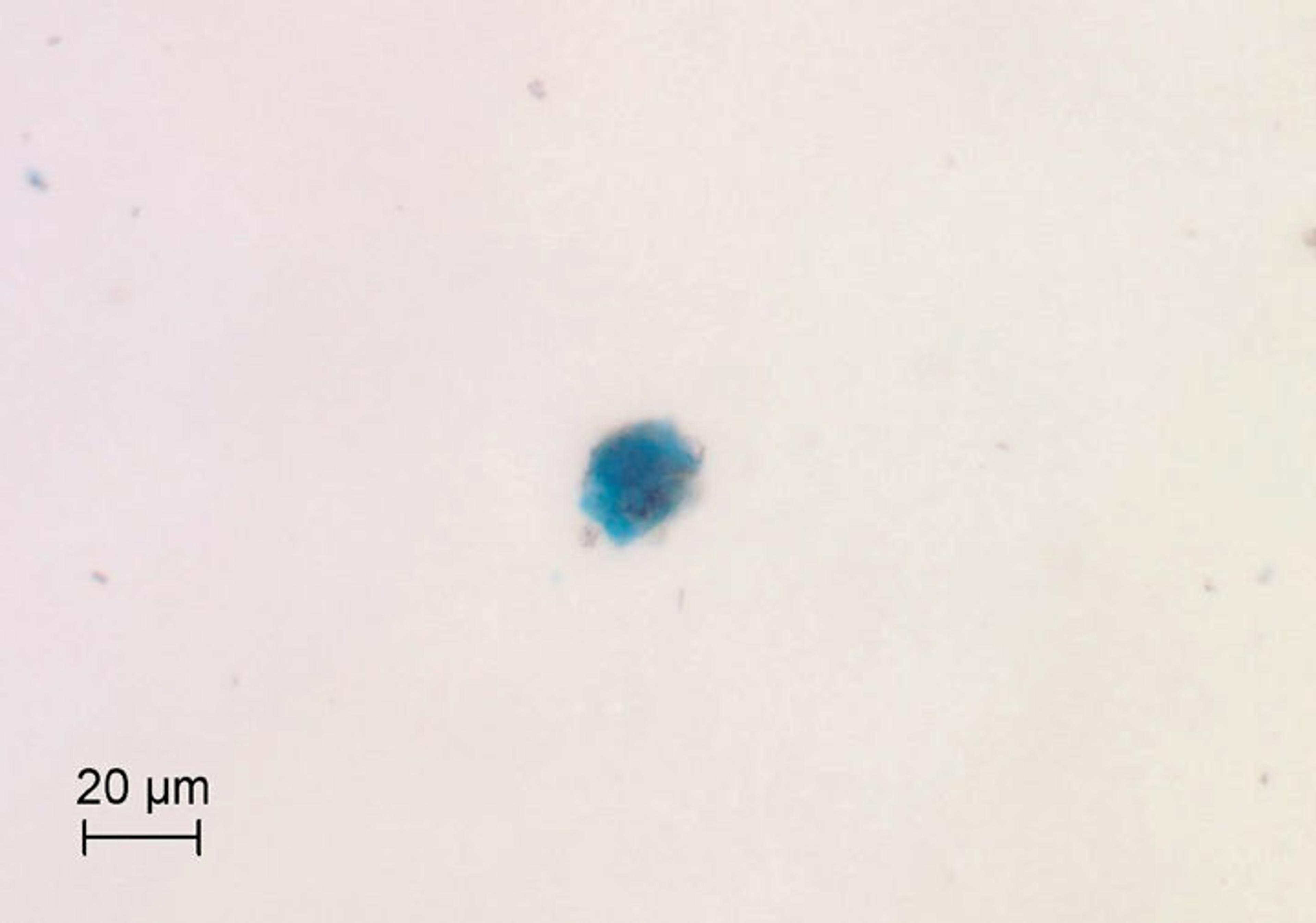

When viewed in polarized light microscopy, the appearance of this pigment was consistent with cobalt blue (fig. 3) rather than smalt, another cobalt-containing blue pigment used historically in Iran. It is worth noting that the manufacturing of cobalt blue began in the late 18th century—long after the Seljuq period—while the other blue pigment found on this roundel was identified as natural ultramarine blue, which has been used since ancient times. Finally, XRF analysis found the golden powder to be almost pure gold. Microscopic observation of this powder revealed that the particles are both small enough and uniform enough in size to be consistent with modern gold powders.

Fig. 3. Plane polarized light image of cobalt blue used on the roundel

These discoveries raised some interesting questions regarding the history of this roundel. Clearly some of the pigments found are consistent with a Seljuq period provenance while others are not. Does the presence of the former pigments confirm the authenticity of this piece? Were the modern pigments selectively applied and then partially removed to look old? Was the piece cleaned too much after modern restorations were made and before The Met acquired the object in 1937? The Museum has planned further work involving scanning electron microscope study of the gypsum plaster and the pigments as well as radiography and ultraviolet fluorescence photography of the roundel in order to gain a better understanding of this piece.

The author wishes to thank Jean-François de Lapérouse, conservator in the Department of Objects Conservation; Federico Carò, research associate in the Department of Scientific Research; and Martina Rugiadi, assistant curator in the Department of Islamic Art for their assistance in this study.

Resources

Alexander, David. Furusiyya: Catalogue, Volume 2. Riyadh: King Abdulaziz Public Library, 1996.

Bacci, Mauro, and Marcello Picollo. "Non-destructive spectroscopic detection of cobalt (II) in paintings and glass." In Studies in Conservation 41 (3) (1996): 136–144.

Eastaugh, Nicholas, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, and Ruth Siddall. The Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary and Optical Microscopy of Historical Pigments. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2008.

Ettinghausen, Richard. "The Flowering of Seljuq Art." In Metropolitan Museum Journal 3 (1970): 113–131.

Holakooei, Parviz, and Amir-Hossein Karimy. "Micro-Raman spectroscopy and X-ray fluorescence spectrometry on the characterization of the Persian pigments used in the pre-seventeenth-century wall paintings of Masjid-i Jāme of Abarqū, central Iran." In Spectrochimica Acta Part A 134 (2015): 419–427.

Keene, Manuel. The Arts of Islam: Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Berlin: Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 1982.

Zick-Nissen, Johanna. "Ziermedaollon, Katalog-Nr. 404." In Museum für Islamische Kunst Berlin, by Klaus Brisch. Berlin-Dahlem: Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 1979.

Related Links

Transformed: Medieval Syrian and Iranian Art in the Early 20th Century, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 17, 2016

Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 24, 2016