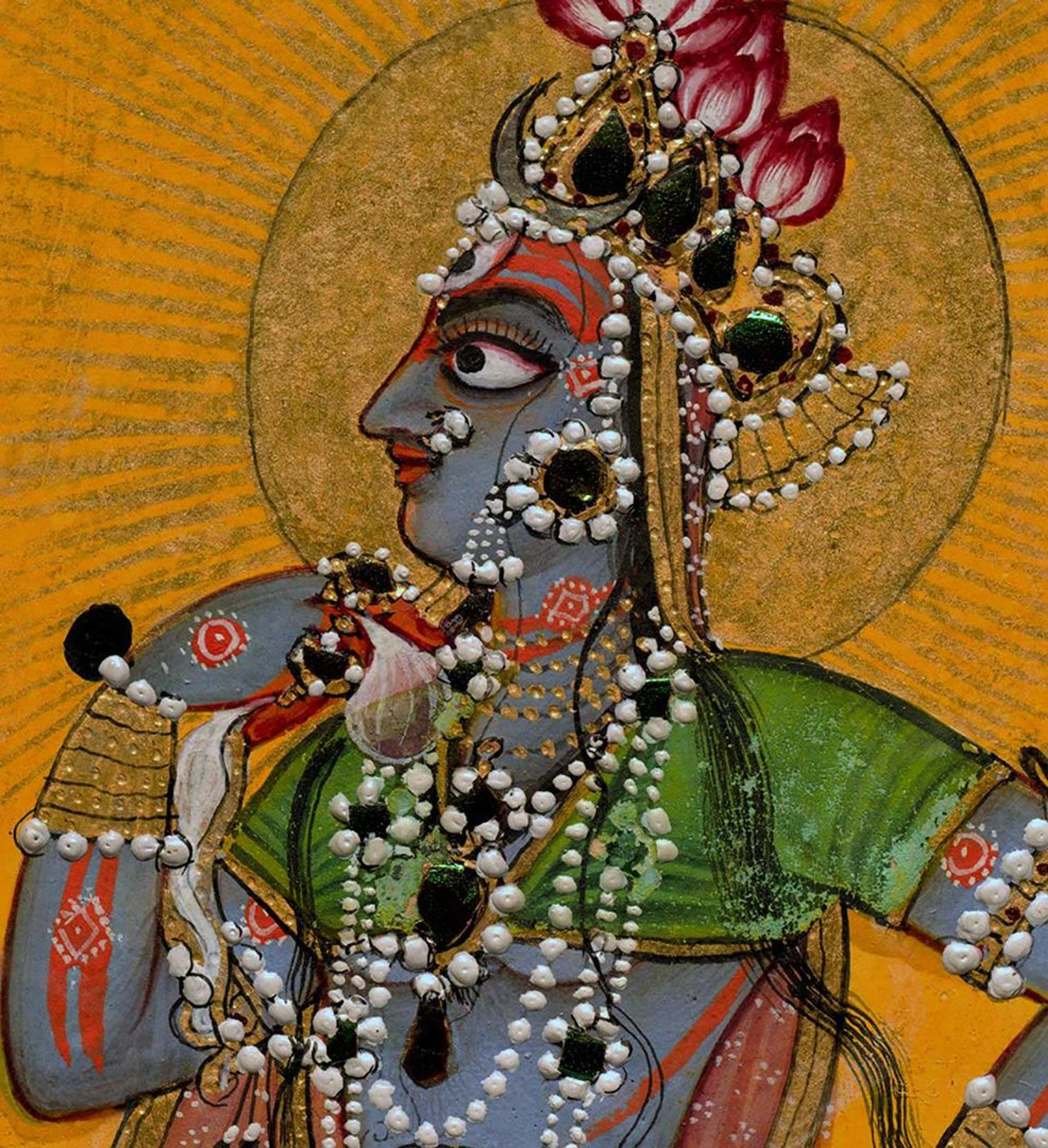

Devi in the Form of Bhadrakali Adored by the Gods, folio from a dispersed Tantric Devi series, ca. 1660–70. Attributed to the Master of the Early Rasamanjari. India, Punjab Hills, kingdom of Basohli. Opaque watercolor, gold, silver, and beetlewing cases on paper, 7 x 6 5/8 in. (17.8 x 16.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Promised Gift of Steven Kossak, The Kronos Collections

This powerful image was created in the 1660s at the very beginning of the Pahari miniature painting tradition. Originally, this folio was one of a series of seventy numbered paintings, each of which showed a different form or facet of the great goddess Devi. Bhadrakali was worshipped as a benevolent aspect of the goddess. Created in the small court of Basohli, this painting and the set to which it belongs are among the earliest miniature paintings to survive from the Pahari courts, located in the Punjab Hills at the foot of the Himalayas. This artwork is on view in Seeing the Divine: Pahari Painting of North India through July 21, 2019.

The emblematic early style is bold and intentionally dramatic. Bhadrakali is shown standing against a field of vibrant yellow—a saturated yellow pigment derived from the urine of a cow fed mango leaves. The artist executed her detailed and dramatic figure by building up many layers of paint, making her presence felt in both her piercing gaze and the opulence of her garments.

The viewer would have been keenly aware of the three-dimensionality of her jewelry, with its raised pearls done in impasto and formed with a brush as the paint dried. Iridescent pieces of beetle-wing, inlaid in her necklace and crown, would have caught the light—as would her radiant halo, done in gold. The sophistication of this articulate and fully realized composition suggests this painting is part of an even earlier and now lost painting tradition.

This representation of the goddess has Sanskrit verses on the back that would have been used by a skilled tantric practitioner to evoke Bhadrakali. She is described as:

Equal to a thousand rays of the rising sun

accompanied by three shining Kalis

worshipped with two bundles of kusha grass

She is everything

Her feet are worshipped by both [Bhairavas]

Accompanied by Bhima and Vahni-priya

She banishes fear

Invoked by Jhankara

adorned with the twenty-two letters

I adore goddess Bhadrakali with the seed mantra bhaim

—translated by Vidya Dehejia, 1999

Affirming Bhadrakali's esoteric meaning are the Hindu gods shown worshiping and making offerings to her. Bhadrakali looks directly at three figures of the goddess Kali that brandish bloodied swords and offer a severed head and skull cups filled with blood to venerate the tantric divinity. Behind her stands the fanged goddess Bhima, who breaks the picture plane by looking directly at the viewer, along with the flame-enshrouded Vahni-priya (consort of Agni, god of fire). Two figures of Shiva kneel at her feet.

The practice of creating sets of inscribed images to evoke the tantric aspects of a divinity finds its closest parallel in Tibet, where tsakali initiation cards were used to align practitioners with Vajrayana Buddhist deities. These Tibetan paintings share the same square format, saturated red borders, and devotional verses on the back. The similarity is not surprising, as trade flowed readily across the high mountain passes separating the two regions. Certainly, the enigmatic text on the verso of the Bhadrakali is in accord with the secret tantric practices that one might undertake with a teacher. It is clear that the deeply religious Pahari courts were looking outside for religious and artistic ideas that they then reworked to serve their own interests. Of course, in the end it was not Buddhist Tibet, but the great Hindu literary traditions and the painting traditions of North India that came to be vitally important to the emerging Pahari idiom.

Note

[1] Vidya Dehejia, Devi: The Great Goddess (Washington, D.C.: The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in association with Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad, and Prestel Verlag, Munich, 1999), 272.

Seeing the Divine: Pahari Painting of North India is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 21, 2019.

View the other artworks in the exhibition.