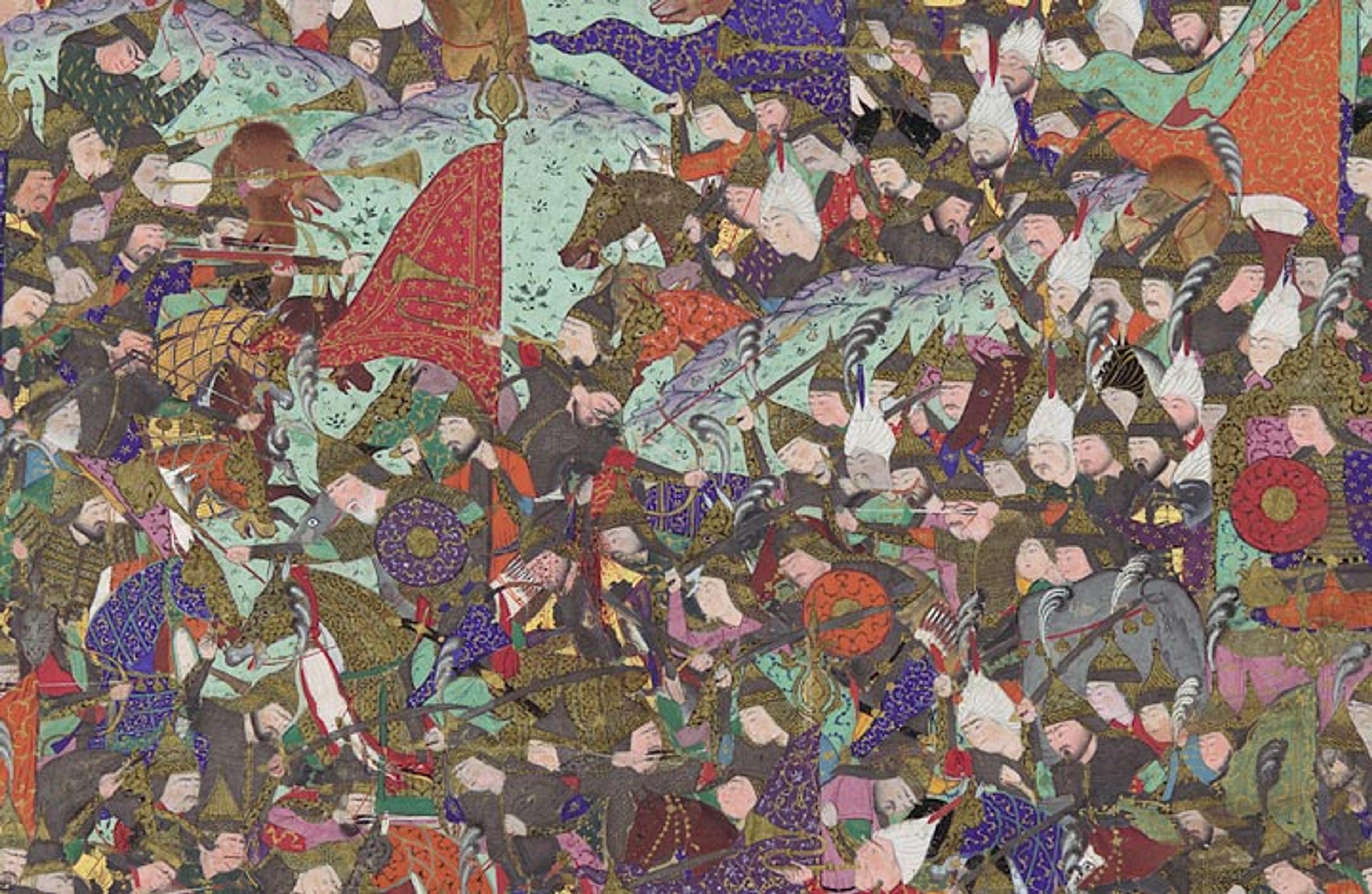

Painting attributed to 'Abd al-Vahhab. "Kai Khusrau Defeats the Army of Makran" (detail), Folio from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, ca. 1525–30. Iran, Tabriz. Islamic. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper; Painting: H. 10 9/16 x W. 7 13/16 in. (H. 26.8 x W. 19.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., 1970 (1970.301.49)

«The recently opened exhibition Power and Piety: Islamic Talismans on the Battlefield, on view through February 13, 2017, highlights some 30 objects from the Departments of Islamic Art and Arms and Armor that explore the role of talismans in the construction, function, and decoration of arms and armor. Used and revered since the Stone Age, talismans are objects believed to be imbued with magical properties, and are intended to guide, empower, and protect the owner from danger, evil, harm, and sickness. In the Islamic world, such objects are considered most effective when bearing verbal and/or visual motifs related to Allah (God), the Prophet Muhammad and other pious figures, as well as verses from the Qur'an.»

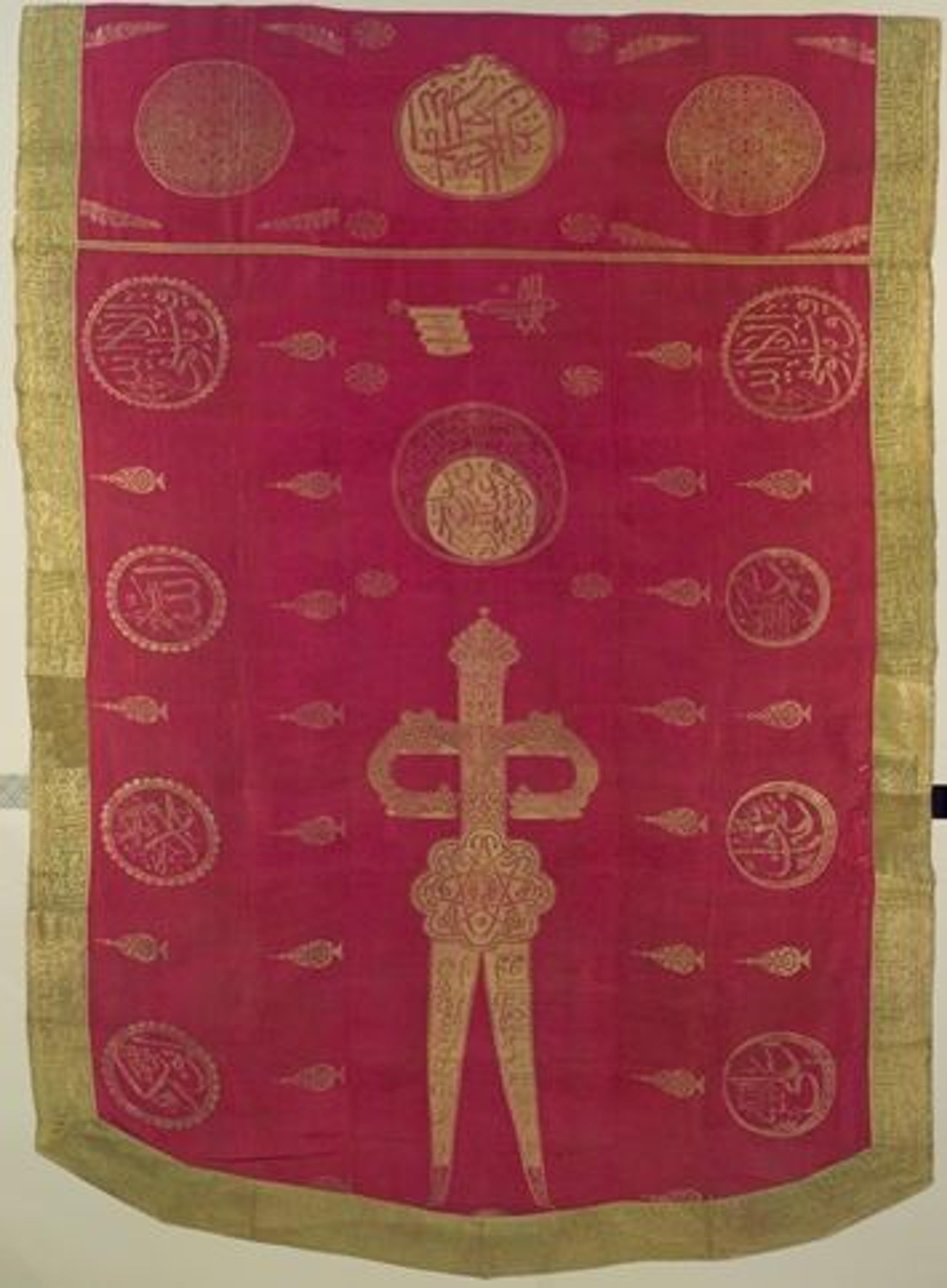

What becomes immediately clear in this exhibition is how some motifs designed to avert evil were ubiquitous throughout the Islamic world. For example, each of the exhibition's three geographic sections—Iran, Turkey, and India and Southeast Asia—references Dhu'l Fiqar, a bifurcated sword imbued with miraculous powers that the Prophet Muhammad gave 'Ali, his cousin and son-in-law, in 625 A.D. during the Battle of Uhud. Dhu'l Fiqar prominently adorns a large Ottoman sançak (banner), which is also emblazoned with inscriptions that point to its likely use in a military context.

Left: Banner, dated A.H. 1235/A.D. 1819–20. Turkey, probably Istanbul. Islamic. Silk, metal-wrapped thread; lampas, brocaded; H. 115 3/4 in. (294 cm), W. 85 1/2 in. (217.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1976 (1976.312)

A personal favorite object of mine is a Southeast Asian short sword, known as a barong, which is adorned with a silver inlaid Dhu'l Fiqar. Surrounding the powerful motif are Arabic letters and numbers that, although seemingly presented at random, are the result of esoteric talismanic calculation tailored to the weapon's owner. Each letter and number most likely signifies Qur'anic passages or other pious phrases that were intended to protect him from harm and danger. (It should also be mentioned that this is the first time Islamic objects from Southeast Asia are being featured in the Department of Islamic Art's galleries!)

Left: Knife (Barong), 19th century. Philippine, Jolo Island or Zamboanga Peninsula. Steel, wood, ivory, silver, copper, gold; L. of blade 15 in. (38.1 cm), W. 3 5/8 in. (9.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (36.25.888a). Right: Detail view of the barong's inscription

While these talismans were meant to empower, they also denoted a sense of vulnerability and a fear of danger and the unknown. When we think of arms and armor, we think of bravery, valor, strength, and might. But the inclusion of these magical verbal and visual motifs demonstrates that there was a need to seek solace and comfort through other means of protection.

Featured at the entrance to the exhibition is a 16th-century Iranian mail shirt made from coiled wire cut into rings to form a tight, interlocking system, which makes it difficult to penetrate. However, despite its secure construction, it still needed metaphysical protection. As a result, each ring was stamped with an inscription that features "Allah" and the names of the members of the Ahl al-Bayt, or "People of the House"—a reference to the Prophet Muhammad and his immediate family: 'Ali; Fatima, his daughter and 'Ali's wife; and Hasan and Husayn, his grandsons. When wearing the mail shirt, the owner's entire upper body was thus cloaked in the protection of God's name as well as those of Islam's holiest family.

Left: Mail shirt, ca. 16th century. Iran, Safavid period (1501–1722). Persian. Iron alloy and copper alloy; L. 34 in. (86.4 cm), W. 57 in. (144.8 cm), Diam. (outside) of links 11/16 (17.0 mm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Gift, 2014 (2014.198). Right: Detail view showing the inscriptions on each individual ring

In some instances, inscriptions and images were strategically placed to protect vital organs or vulnerable parts of the body such as the face. A Deccan Indian helmet features a distinct pierced face guard that offered protection without impairing the wearer's vision. At the center of the cutout for the nose is "O 'Ali," and surrounding the border of the cutout is an inscription that reads, "There is no hero or man like 'Ali; there is no sword like Dhu'l Fiqar. Help from Allah and a speedy victory."

Right: Helmet (with face guard), 17th–19th century. Deccan, Indian. Steel, gold, copper alloy; Helmet (a): H. including mail 24 in. (61 cm), H. including nasal 17 in. (43.2 cm), W. 9 1/4 in. (23.5 cm), D. 10 5/8 in. (27 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (36.25.63a)

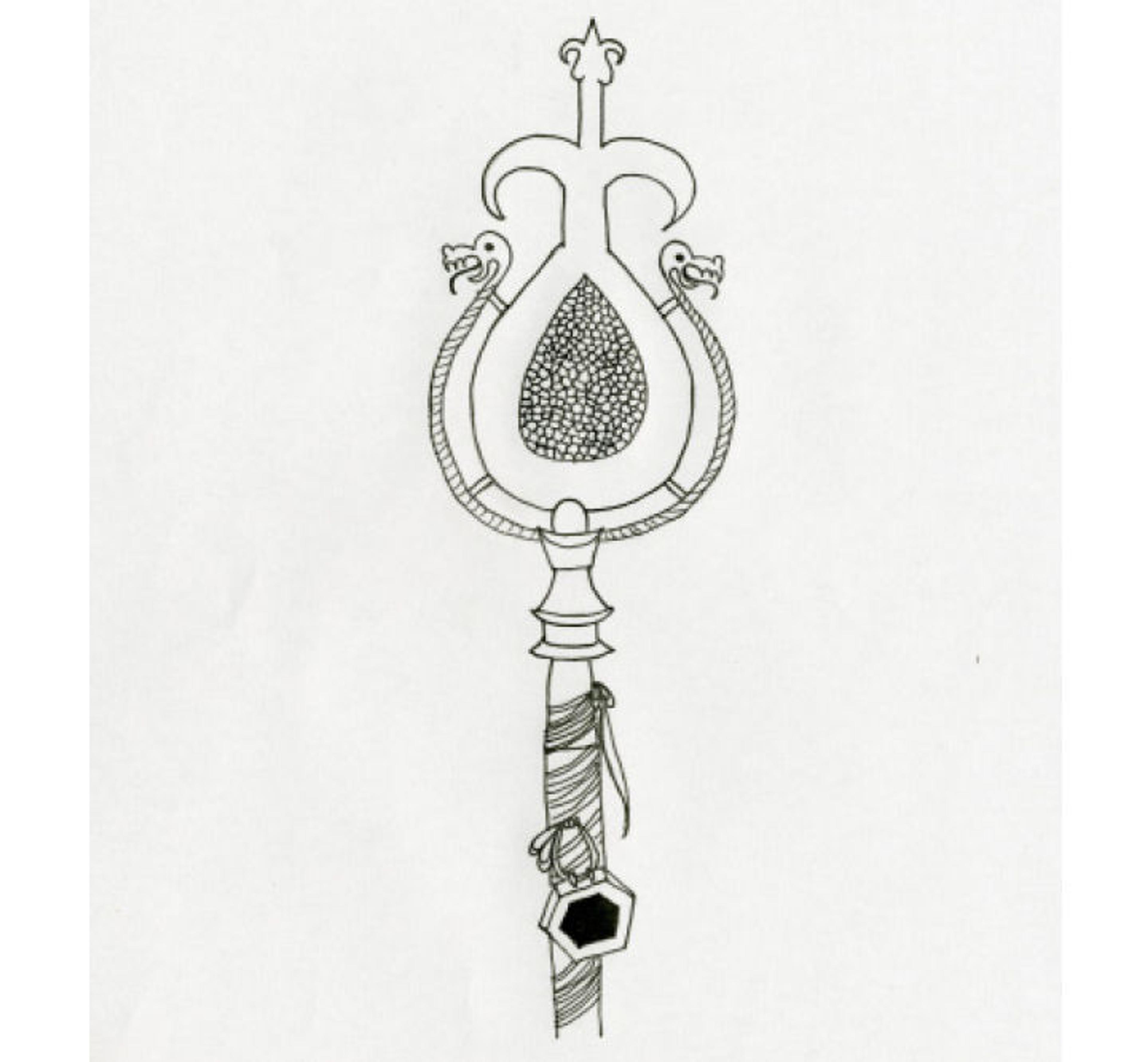

The final section of the exhibition concludes with a group of personal items that communicates a more intimate and sensitive side to war. The objects here include small Qur'ans and prayer books that were carried for protection and could be consulted for guidance and prayer. The tiniest object on display is an octagonal sançak Qur'an, which would have been placed in a metal box or pouch and attached to the shafts of military standards, as shown below. The manuscripts were also sometimes worn as armbands or around a soldier's neck, or they could have been affixed to weapons or ceremonial objects.

Portable Qur'an manuscript, 17th century. Iran or Turkey. Islamic. Ink and gold on paper; leather binding; H. 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm), W. 1 1/4in. (3.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Joseph W. Drexel, 1889 (89.2.2156)

Image of a banner Qur'an attached to a military standard. Drawing by Rachel Parikh

Everyone can relate to being afraid or anxious about what is uncertain—such emotions are what make us human—and every culture has methods and practices that assuage these feelings. Power and Piety sheds light on this aspect of human nature through gleaming and glorious objects from Islamic history and through talismans used when they were most needed: in battle.

Related Links

Power and Piety: Islamic Talismans on the Battlefield, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through February 13, 2017

Learn more about the role of talismans in arms and armor throughout the Islamic world in the digital catalogue authored by exhibition co-curators Maryam Ekhtiar and Rachel Parikh.