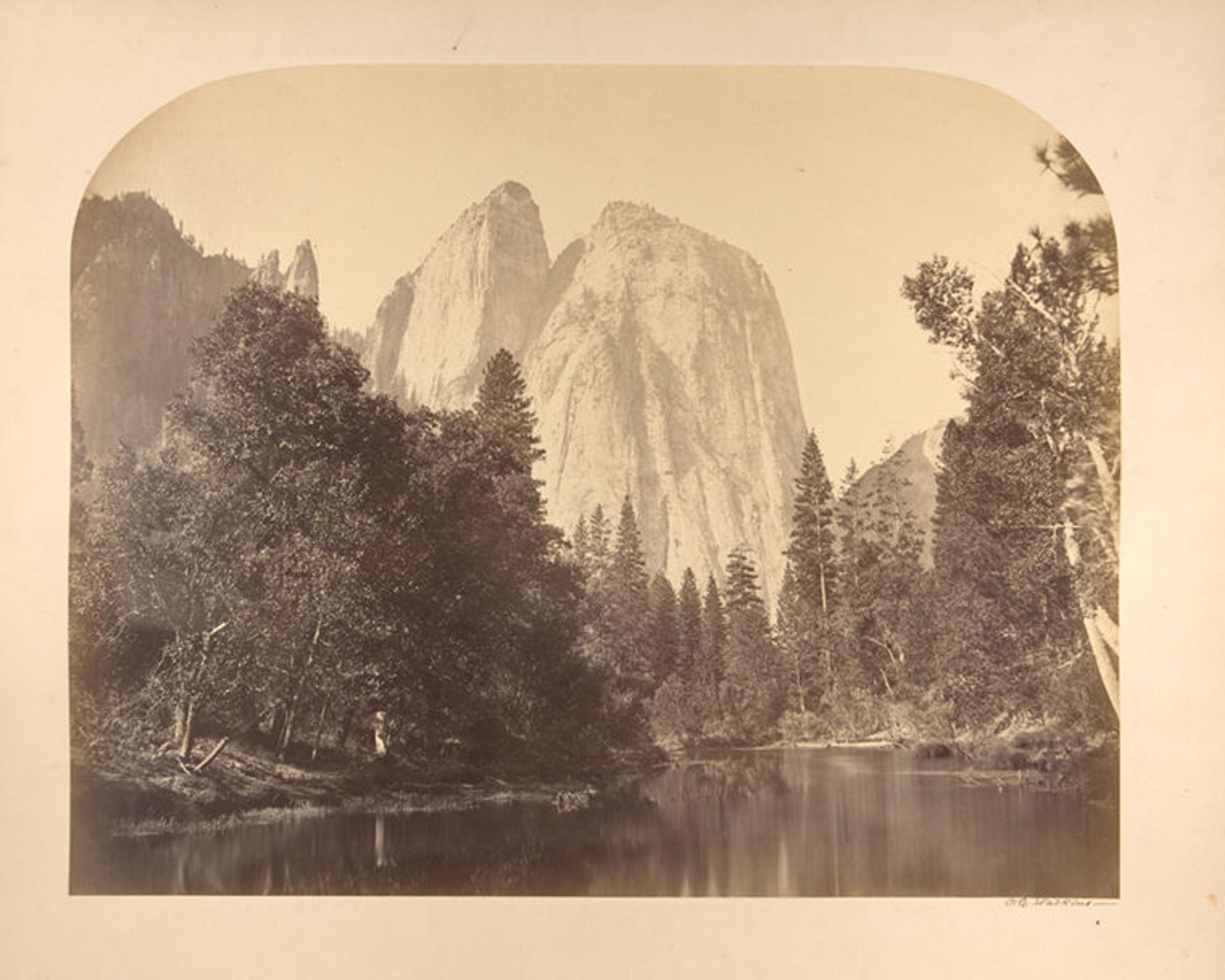

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829–1916). Cathedral Rock, River View, 1861. Albumen silver print from glass negative, 16 3/8 x 23 1/2 in. (41.5 x 59.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005 (2005.100.1273)

«Among the joys of Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings is that it tells two interwoven stories. First, there's the narrative embedded in the exhibition's title, of how Cole's art was informed by his youth in industrial Britain. Into this biography, the exhibition's curators smartly weave the development of his ideas about America as he expressed them in pictorial form—paintings that helped lead America to value not just its land but its landscapes, too. Within Cole is the beginning of a nearly thirty-year process leading to the first federal preservation of a specific landscape—the establishment of Yosemite and the nearby Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias in 1864—as what we now call a national park, an idea that will spread across the United States and then the world. Cole reveals how American art grew into an agent outside art's own history.»

As Americans moved off the Atlantic seaboard in the early nineteenth century, around the time Cole was born in England, they encountered what they considered wilderness and dense forests full of wild animals. They harvested trees, converting forests into land that was then used for mostly agrarian purposes, but also for emerging industry. Before long, such rapaciousness on a national scale began to be questioned, especially by artists and writers.

In a letter dated 1832 (and first published in 1844), ethnographer and illustrator George Catlin suggested that land lightly touched by Anglo-Europeans—principally the Great Plains, a place he figured that an Atlantic-hugging America was decades away from reaching—was worthy of "preservation and protection" because "the further we become separate from that pristine wildness and beauty, the more pleasure does the mind of enlightened man feel in recurring to those scenes." James Fenimore Cooper's 1823 novel, The Pioneers, considered the young nation's encounter with wilderness, and questioned our address of it. As 1836 approached, the year in which Cole painted his mighty View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, the painting to which The Met's extraordinary exhibition builds, a small number of American elites went a step further and began to wonder if unrestrained, forests-eliminating westering for growth's sake was in the best interests of the nation.

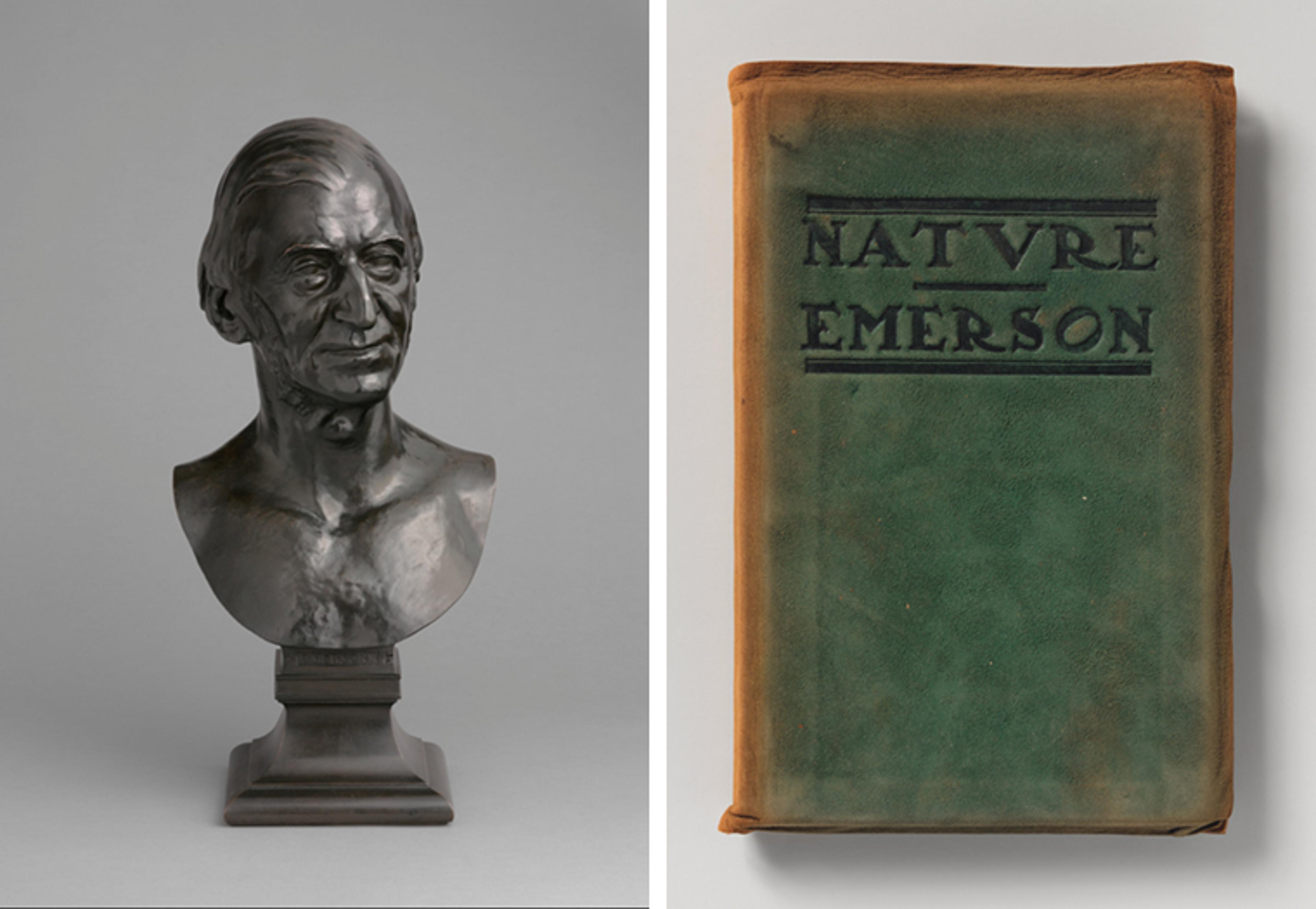

Remarkably, the two intellectual titans of the era, Cole and Ralph Waldo Emerson, seem to have come to different expressions of this idea at almost the exact same moment. Also in 1836, Emerson published his great book-length essay, Nature, which urged Americans to find pleasure, meaning, and value in the environment. Emerson argued that a key difference between "land" and "landscape" was that Americans thought of the former in terms of its mineral, timber, or agrarian potential, and that the latter's value could be in its provision of pleasure (rather than in commercial use).

The charming landscape which I saw this morning is indubitably made up of some twenty or thirty farms. Miller owns this field, Locke that, and Manning the woodland beyond. But none of them owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is the poet.

Left: Daniel Chester French (American, 1850–1931). Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1879, cast 1906–7. Bronze, 22 1/2 x 10 1/4 x 9 in. (57.2 c 26 x 22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Artist, 1907 (07.101). Right: Ralph Waldo Emerson (American, 1803–1882). Nature, 1905. Published by Roycroft (1895–1938). 8 11/16 x 5 1/2 x 9/16 in. (22 x 14 x 1.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Morrison Heckscher, 2014 (2014.640.3[12])

Emerson had first written a version of that passage in his journal on January 16, 1836—at just about the same time Cole published his "Essay on American Scenery" in the January issue of American Monthly magazine. Cole's essay argued that the United States was full of beauty that Americans had yet to appreciate fully. As 1836 progressed, Emerson and Cole continued to build upon their shared idea: at the same time Emerson was putting the finishing touches on Nature ahead of its late-summer publication, Cole painted The Oxbow. In both prose and oil paint, Emerson's poet had arrived.

The Oxbow shows the west-facing view from atop Mount Holyoke, a 935-foot mountain in central Massachusetts. The forested left-hand side of the painting both looks toward and represents the still-forested West—the land young Americans were racing to fill, the forests they rushed to eliminate so that the nation's new land could be converted to agricultural use. The right-hand side depicts how that story had played out in the previous generation, with some twenty or thirty farms, and the deforested woodland beyond. It is this representation of the farms where Cole most amplifies Emerson. (Or is it Emerson who amplifies Cole?) In The Oxbow, the unification of the woodlands, both in the foreground and on the distant hill with farmland throughout, are integrated into a landscape.

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (detail), 1836. Oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 76 in. (130.8 x 193 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908 (08.228)

The Cole-Emerson coincidence is a stunning moment. So far as historians have been able to tell, Emerson and Cole were not in correspondence. There is no direct evidence that either even knew of the other's work. (Exhibition co-curator Betsy Kornhauser and I discussed this on the Modern Art Notes Podcast.)

Both men would continue their arguments for landscape's value in the years to come. In the 1840s, Cole proposed (but ultimately failed to write) a book that would address, in part, the need to save and perpetuate landscapes fast being lost to American expansionism. Emerson advocated for parks and preservation in 1844 when he published The Young American. "The interminable forests should become graceful parks, for use in delight," he wrote.

Others began to chime in. In 1851, New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley urged America to "spare, preserve, and cherish some portion of your primitive forests." (In other writings, however, the malleable Greeley argued that America should cut down more forests, faster.) In 1858, Emerson's frenemy Henry David Thoreau wrote an essay on Maine, which he first published in the Atlantic Monthly. When that essay was reprinted in The Maine Woods (1864), Thoreau added a passage urging the creation of "national preserves."

These scattered references from elites hardly added up to a movement, but they carried the day when America explicitly preserved its first entire landscape. The protagonist was another Emerson acolyte, a Boston-area Unitarian minister named Thomas Starr King. Among Starr King's talents was an ability to apply abstract Emersonian ideas to specific places. His 1859 book, The White Hills, published just before Starr King moved to California, joined Emerson's ideas about landscape to contemporary art and poetry criticism, and presented them within a guidebook about New Hampshire's White Mountains, arguably the first place that Americans began to embrace and enjoy an entire landscape. Just as The White Hills became a top seller—it went through almost a dozen printings—Starr King was busy discovering the next landscape about which he would write, California's Yosemite Valley.

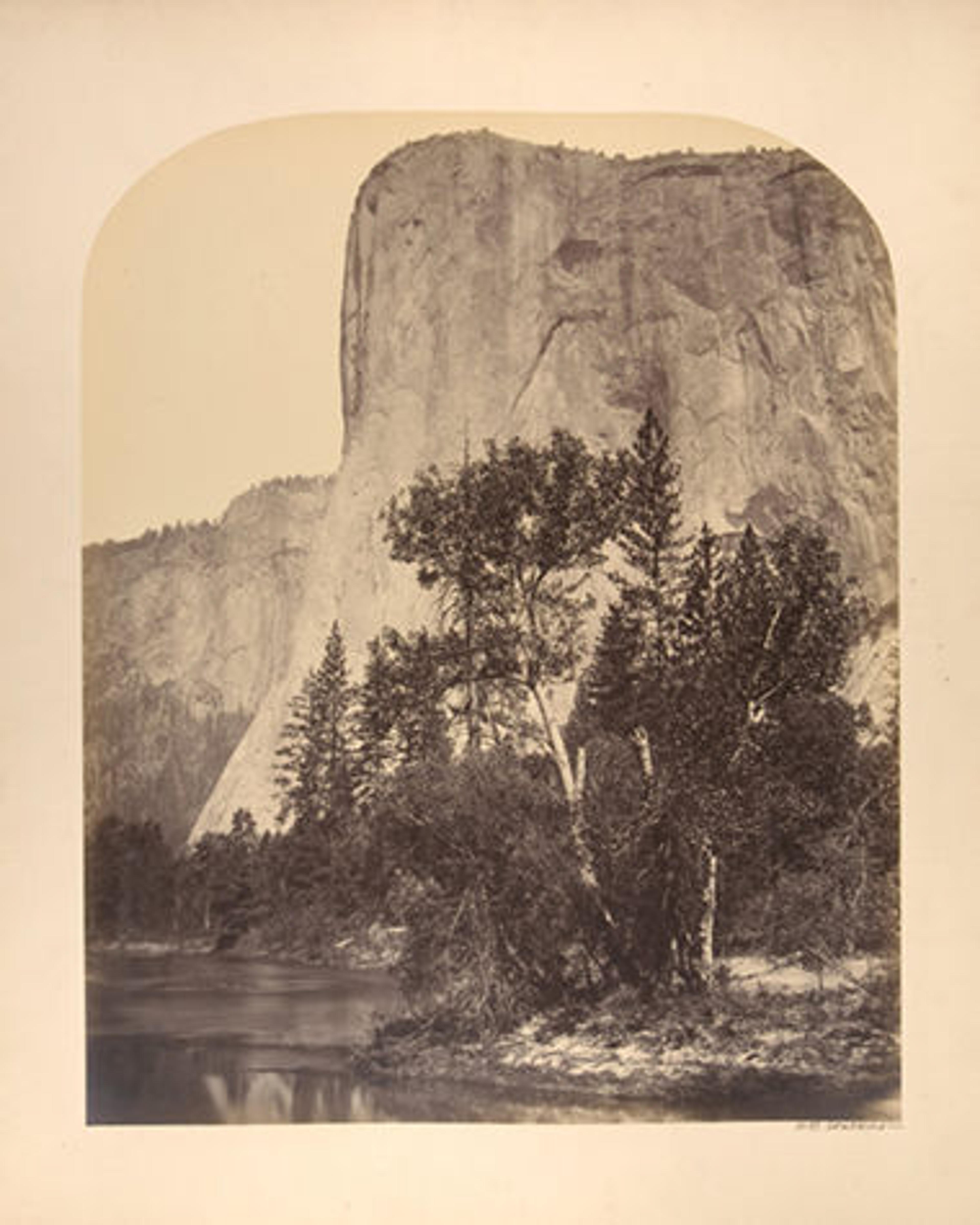

Right: Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829–1916). El Capitan, Yosemite, 1865–66. Albumen silver print from glass negative. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1970 (1970.540.4)

In 1860 and 1861, just as southern states began to leave the Union, Starr King published a series of essays about Yosemite and the nearby Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias in the Boston Evening Transcript, the newspaper of the day's progressive elite. Through John Frémont, the young Republican Party's 1856 presidential nominee, and his even more influential wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, Starr King had come to know an artist from San Francisco named Carleton Watkins. Starr King immediately recognized that Watkins could help America see this "new" landscape as he did.

Watkins traveled to Yosemite just as the Civil War began in 1861, taking with him the world's largest camera, apparently of his own design (and maybe of his own construction, too). During that summer, Watkins made thirty-four large-format pictures of the valley and the Mariposa Grove, and around one hundred smaller stereographs. (Thirty of the so-called mammoth-plate pictures are in The Met collection.)

In 1864, Watkins's pictures would be the key documents wielded by a small group of San Franciscans who advocated for the preservation of Yosemite. In the immediate wake of Starr King's unexpected death that spring, Congress passed and President Abraham Lincoln signed into law a bill preserving Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove "in perpetuity." The next year, Frederick Law Olmsted wrote a report for the state of California detailing what this new thing, a nature park, should be. Olmsted's report, one of the greatest rhetorical essays of the American nineteenth century, adapts significant chunks of his friend Emerson's Nature, notes the outsize influence of artists in the Yosemite idea, and joined the concept to a cause broader than the landscape itself: burgeoning Gilded Age inequality.

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829–1916). Tasayac, or the Half Dome, 4967 Feet, 1861. Albumen silver print from glass negative, 15 13/16 x 20 1/4 in. (40.1 x 51.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005 (2005.100.1260)

Before the Cole-Emerson construction of landscape, Americans tended to venerate individual features in the land, such as Natural Bridge, a stone arch that was once on Thomas Jefferson's land in Virginia. Cole and Emerson's emphasis on landscape opened up a way for broad swaths of land to be variously valued, a concept that made room for the United States to establish 60 national parks, 129 national monuments, and 154 national forests, which contain over 750 "wilderness areas" that have been specifically preserved and protected from development. Nearly one hundred countries have adopted the idea of nature parks, the root of which is here, in Thomas Cole's Journey.

Related Content

Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 13, 2018.

Read a blog series about Thomas Cole on Now at The Met.

See more digital content related to Thomas Cole, including a walkthrough of the exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase in The Met Store.

Tyler Green is the host of the Modern Art Notes Podcast.