Do you believe in unicorns? Medieval Europeans did. In tales of faraway lands and magical beasts, unicorns were a favorite topic for kings, queens, knights, and ladies. They even thought that unicorn horns had special healing powers.

Until the 1700s, wealthy rulers across Europe would buy unicorn horns—that is, what they believed to be unicorn horns—considering them to be magic potions.

An example of a cup made from an animal's horn. Beaker, ca. 1480. Attributed to Hans Greiff (German, active ca. 1470-died 1516 Ingolstadt). German, made in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. Horn, gilded silver mounts and cover, overall: 9 1/2 x 2 9/16 x 3 1/16 in. (24.1 x 6.4 x 7.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.496a, b)

When they were feeling sick, they would shave off little pieces of the horn to put in their beverages. It was also believed that unicorn potions could protect people from being poisoned, which was always a possibility at a time when rulers were often at odds with their own family members in battles for the throne. Queen Elizabeth I was known to drink from a golden goblet carved from a unicorn horn because she believed it would purify water. The Met collection includes a horn goblet less luxurious than Queen Elizabeth’s cup—made from the horn of a species of mountain goat called an ibex, which was also thought to have healing power. But neither it nor a "unicorn horn" can really protect people against poison!

In a gallery at The Met Cloisters, you can see both the Unicorn Tapestries, which tell the story of the hunt for a magical unicorn, and a "unicorn horn."

Gallery 17 at The Met Cloisters

Look at what's going on in The Unicorn Purifies Water. It was fabled that a unicorn could dip its horn into water, purifying it and making it ready to drink. We see many different kinds of animals that aren't native to Europe–lions, a hyena, a cat-like animal called a genet, and a panther–all with open mouths, ready to quench their thirst with fresh water. In awe of the magic unfolding before them, a group of hunters gathers around the unicorn, frozen in their tracks. In legends about these mythical creatures, hunters bravely pursued unicorns into deep woods in an attempt to capture one and take its horn. Because of their supposed healing powers, unicorn horns were very valuable objects.

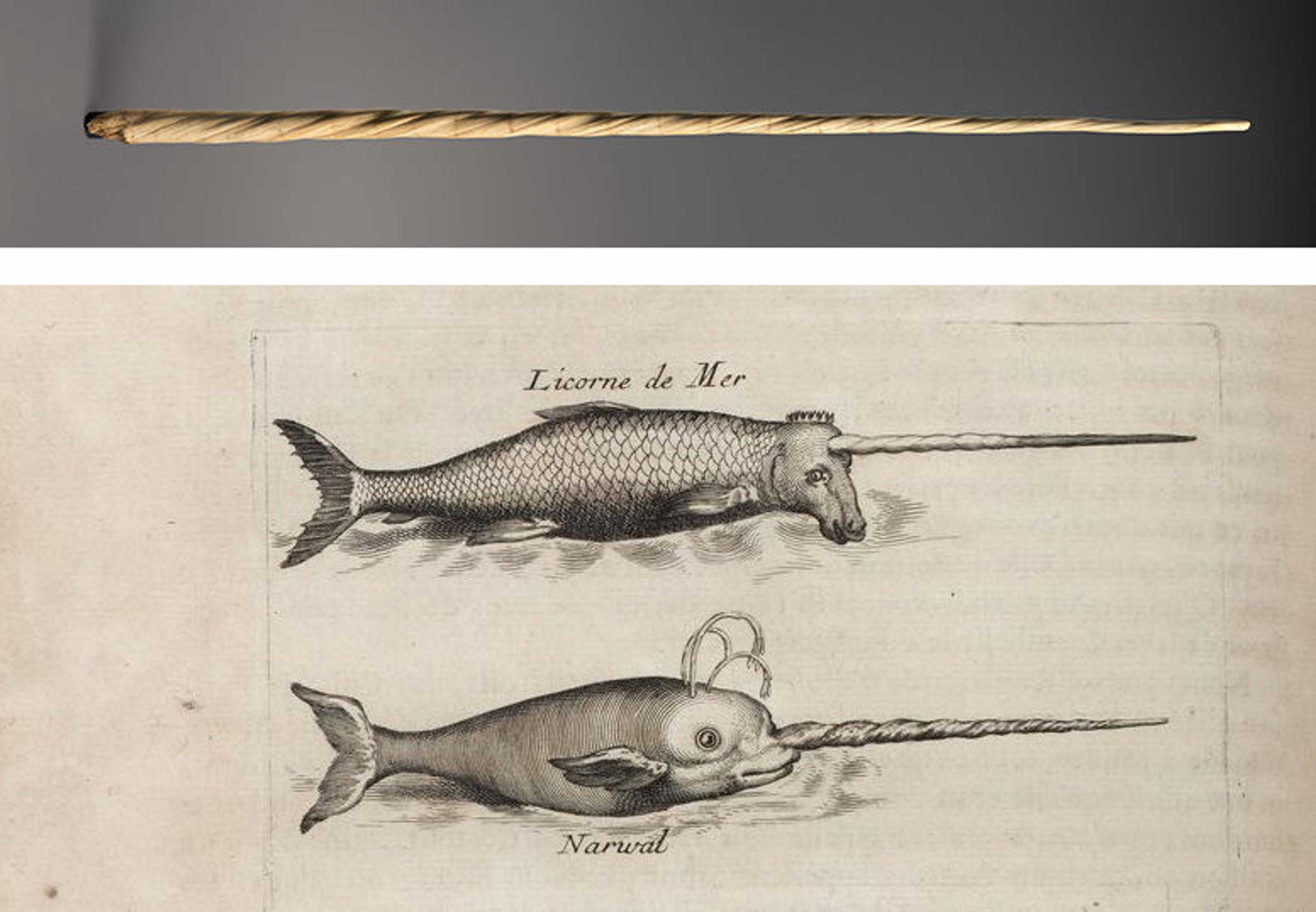

Above: Narwhal Tusk, 17th–19th century(?). Narwhal tusk, 80 1/2 x 2 5/8 in. (204.5 x 6.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1981 (INST.1981.8) | Below: Licorne de mer (sea unicorn) from Pierre Pomet's Histoire générale des drogues, 1748. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

The second object in the gallery isn't actually a unicorn horn at all. Instead, it is a narwhal tusk: the extremely long tooth of a type of whale that lives in the Arctic Ocean near Greenland, Canada, Scandinavia and Russia. As you may have guessed by now, many people in the Middle Ages believed that narwhal tusks were actually unicorn horns. Narwhal were hunted in the waters of Northern Europe; their horns were particularly prized by rulers in Scotland and Denmark. Hunters in the North American Arctic likely included ancestors of today’s Inuit people. Traders sold supposed "unicorn horns" to wealthy European clients for large sums of money. Such long, spiraling narwhal tusks belonged to kings, queens, and princes, and were sometimes part of a church’s collection of precious objects.

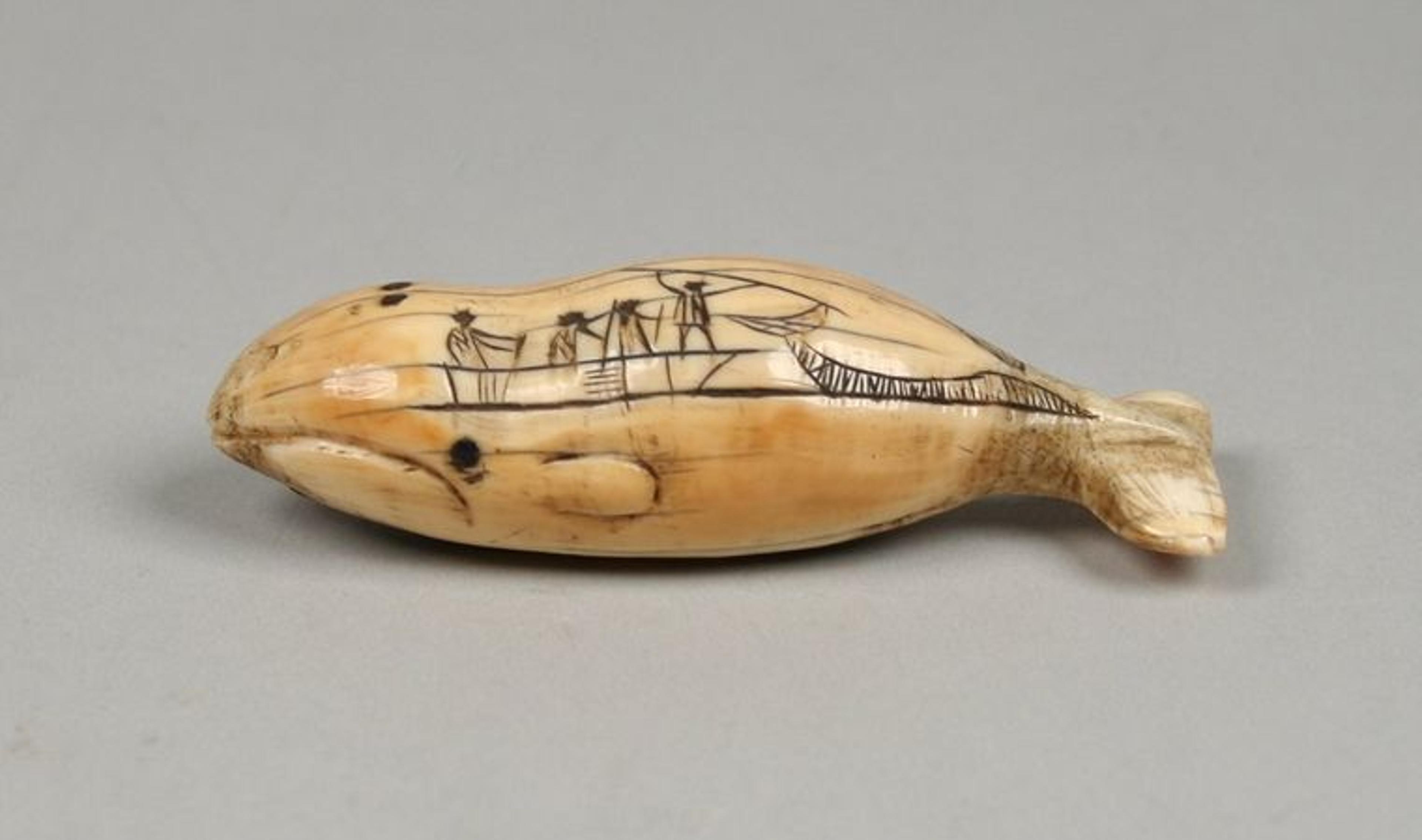

This object, carved in the shape of a whale by an Inuit artist in Alaska, shows a scene from a hunt. Whale, 1830-1860. Inuit, made in the United States, Alaska. Ivory (walrus), 7/8 x 1 x 2 7/8 in. (2.2 x 2.5 x 7.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.522)

Because their knowledge of the world was much smaller than ours is today, most people in medieval Europe had never seen narwhals before. Even today, scientists are still learning new facts about the narwhal and its tusk.

Dr. Martin Nweeia, one of the leading narwhal specialists of the 21st century, is responsible for uncovering a great deal of what we know about the narwhal. The narwhal tusk—actually a tooth—is normally grown by males. Yet this tooth isn’t used for chewing; narwhals actually have no teeth in their mouth, and swallow fish whole! The tusk instead seems to be used as a tool for sensing changes in the environment, like differences in water temperature, salt level, and the presence of nearby prey. Scientists once thought that narwhal tusks were used for fighting, but narwhals actually rub their horns against each other for cleaning. These tusks, which can grow to a staggering nine feet, aren’t as stiff as they may seem. They’re actually very flexible and can bend up to a foot in either direction.

The unicorns that sparked the medieval imagination may have been a dream, but narwhals show that there are many extraordinary creatures that inhabit this earth that are as curious and elusive as the unicorn.