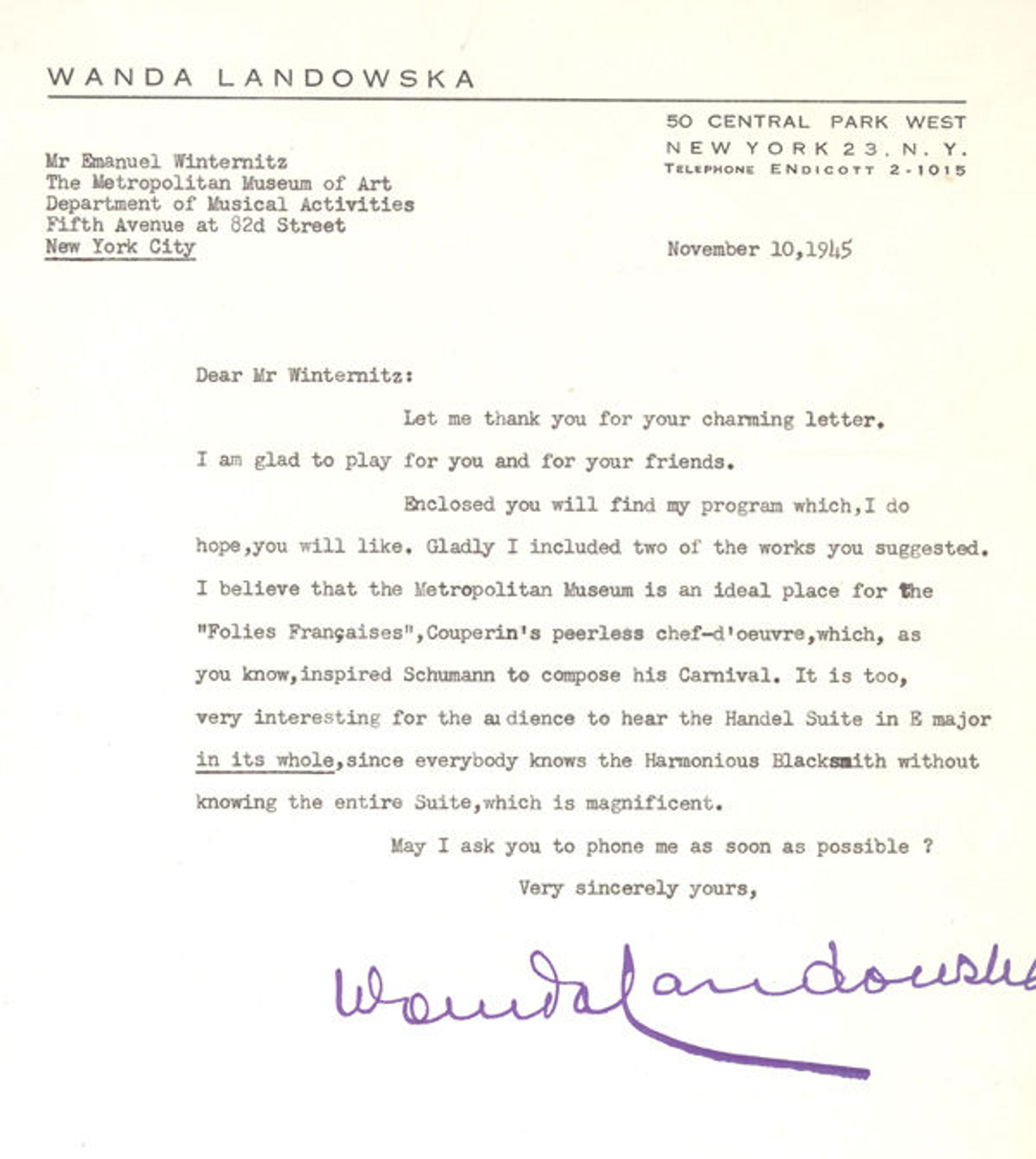

Letter from Wanda Landowska to Emanuel Winternitz, November 10, 1945

«Among the many prominent musicians whom curator Emanuel Winternitz attracted to the Met to perform in his free Member Concerts was the distinguished Warsaw-born pianist and harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, who, like Winternitz, fled the Nazis in Europe and found a permanent home in the United States. Landowska is remembered today for having reintroduced the harpsichord to concert halls, beginning in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century, after almost a century of being largely displaced by the more powerful piano.»

Landowska's friends Manuel de Falla and Francis Poulenc composed new harpsichord music for her, but much of her concert repertoire was original pieces from the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries that had fallen out of fashion since the advent of the large concert halls and large orchestras of the nineteenth century. She thus played a notable role in the historically informed performance movement in the United States, which Winternitz fostered at the Met. Landowska also taught generations of musicians—including Ralph Kirkpatrick, who also performed at a number of the Museum's Member Concerts.

Left: A 1928 Pleyel harpsichord with two keyboards, of the type commissioned by Wanda Landowska from the French manufacturer. Pleyel et Cie. Harpsichord, 1928. French. Wood, various materials. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Laura La Forge Webb, in memory of Frank La Forge, 1979 (1979.523.1.2)

Landowska's concertizing at the Met was not a Winternitz innovation, however. Though Landowska lived in France for much of her adult life, she visited the United States several times, and Frances Morris, the curator responsible for the musical instruments collection from 1896 until her retirement in 1929, invited her to play at the Met in 1923. As the November 1923 Bulletin (Vol. 18, No. 12, Part 1, 293) reported:

On Sunday, December 23, at 4 o'clock in the Museum Lecture Hall, Mme. Wanda Landowska will play upon the harpsichord some of the early music specially written for that instrument, of which Mme. Landowska has said, "The harpsichord reigned 'en Maître' during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. . . . It has, like the organ, two keyboards and a great number of registers, imitating flute, violin, oboe, and bagpipe, which vivify the works with glowing colors of ancient 'vitraux.' Its deep registers make us feel the dark profoundness of certain preludes and fugues of Bach. There is brilliancy and joyous brightness in its two keyboards, which in struggling with each other let our sparkles and give to the sonatas of Scarlatti that devilish genuine Neapolitan verve." Her own harpsichord is one reconstructed after the authentic harpsichord of Bach. Such a concert has a peculiar appropriateness in the Museum with its many fine old instruments belonging to the Crosby Brown Collection.

On Christmas Day 1927, Landowska performed a free recital at the Met—a reminder to modern audiences of the days in which the Museum was not only open seven days a week, but 365 days a year, and felt an especial obligation to provide special events on the holidays, which were among the few times when working people might be assured of time for such luxuries as museum- and concert-going.

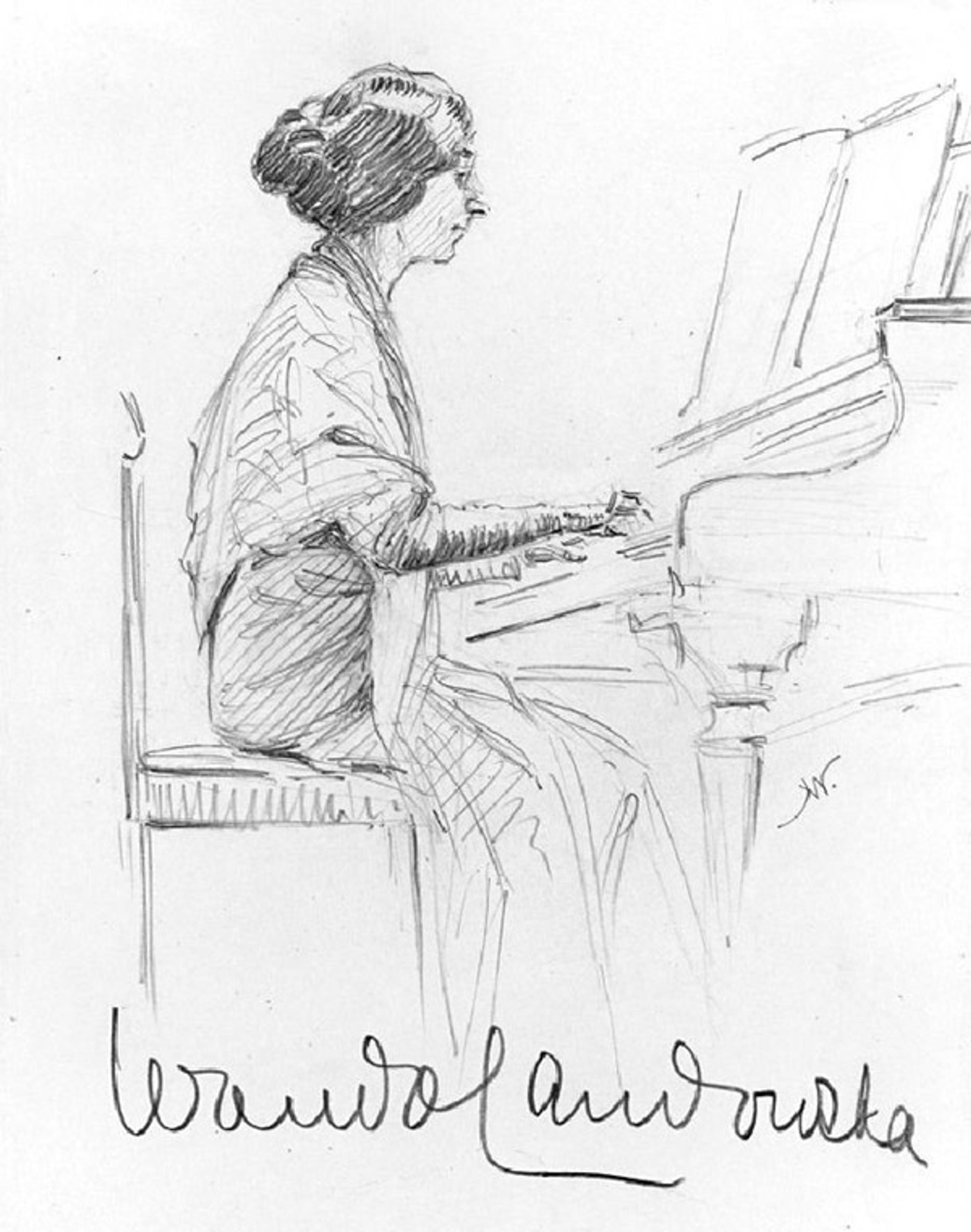

Left: Hilda Wiener (1877-1940). Wanda Landowska Playing Bach in Brussels, 1930s. Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons

Landowska fled France and landed at Ellis Island on the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. Because of the U.S. quickly declaring war, delays at Ellis Island were inevitably protracted, and Landowska entertained herself and her fellow refugees by playing an old piano that she spotted in the Arrivals Hall. She was allowed to enter the U.S. after virtually every prominent musician in New York signed a petition supporting her. Soon afterwards, on February 21, 1942, she gave a concert at Town Hall of Bach's Goldberg Variations on the harpsichord—the first time since the nineteenth century that New Yorkers had heard those pieces played on the instrument for which they were written. As Virgil Thomson wrote in his review of the concert:

There does not exist in the world today, nor has there existed in my lifetime, another soloist of this or of any instrument whose work is so dependable, so authoritative and so thoroughly satisfactory. From all the points of view—historical knowledge, style, taste, understanding and spontaneous musicality—her renderings of harpsichord repertoire are, for our epoch, definitive. Criticism is unavailing against them, has been so, indeed, for thirty years.

She became a sensation, and settled permanently in the United States.

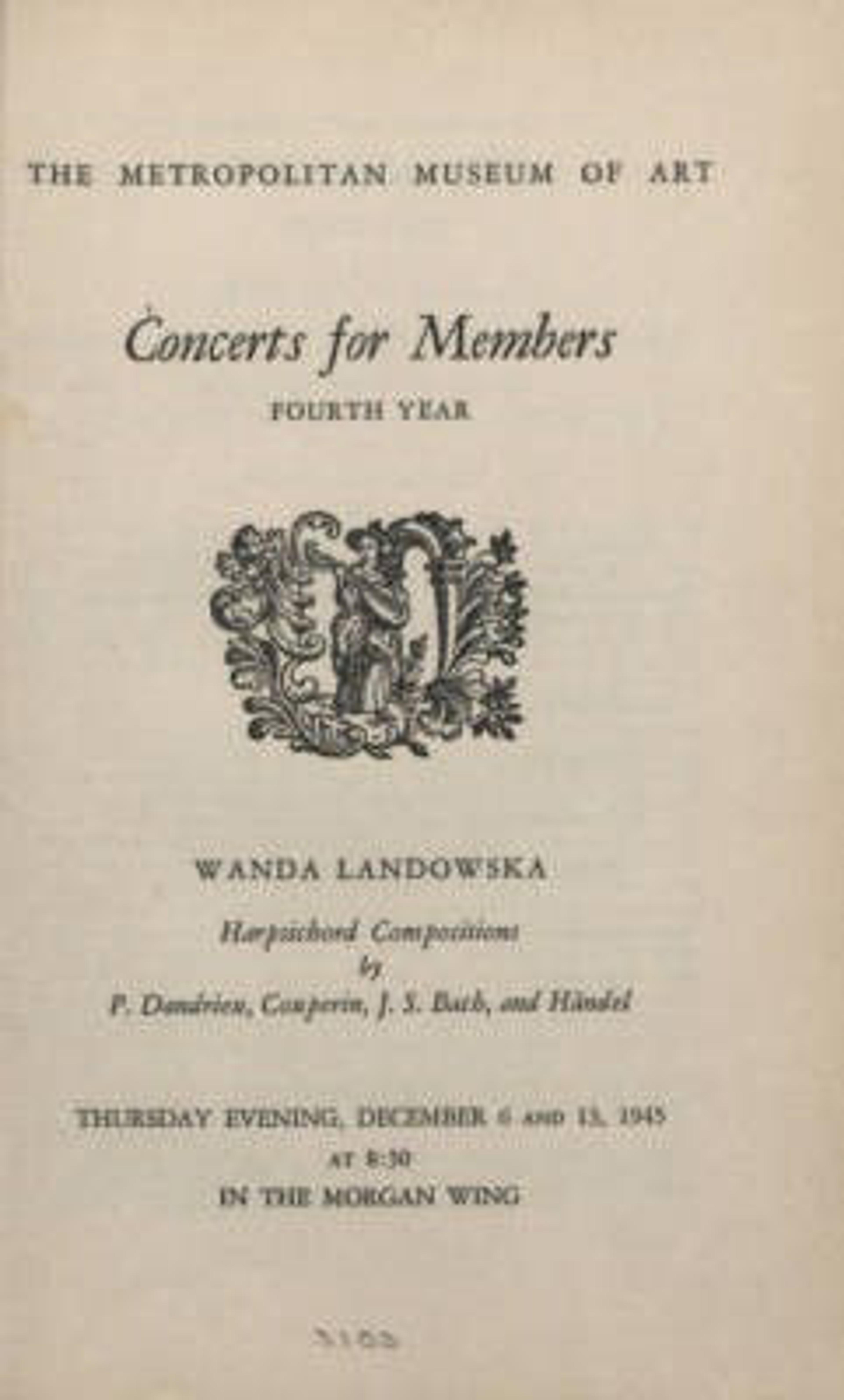

Right: Program cover for Landowska's 1945 Member Concerts

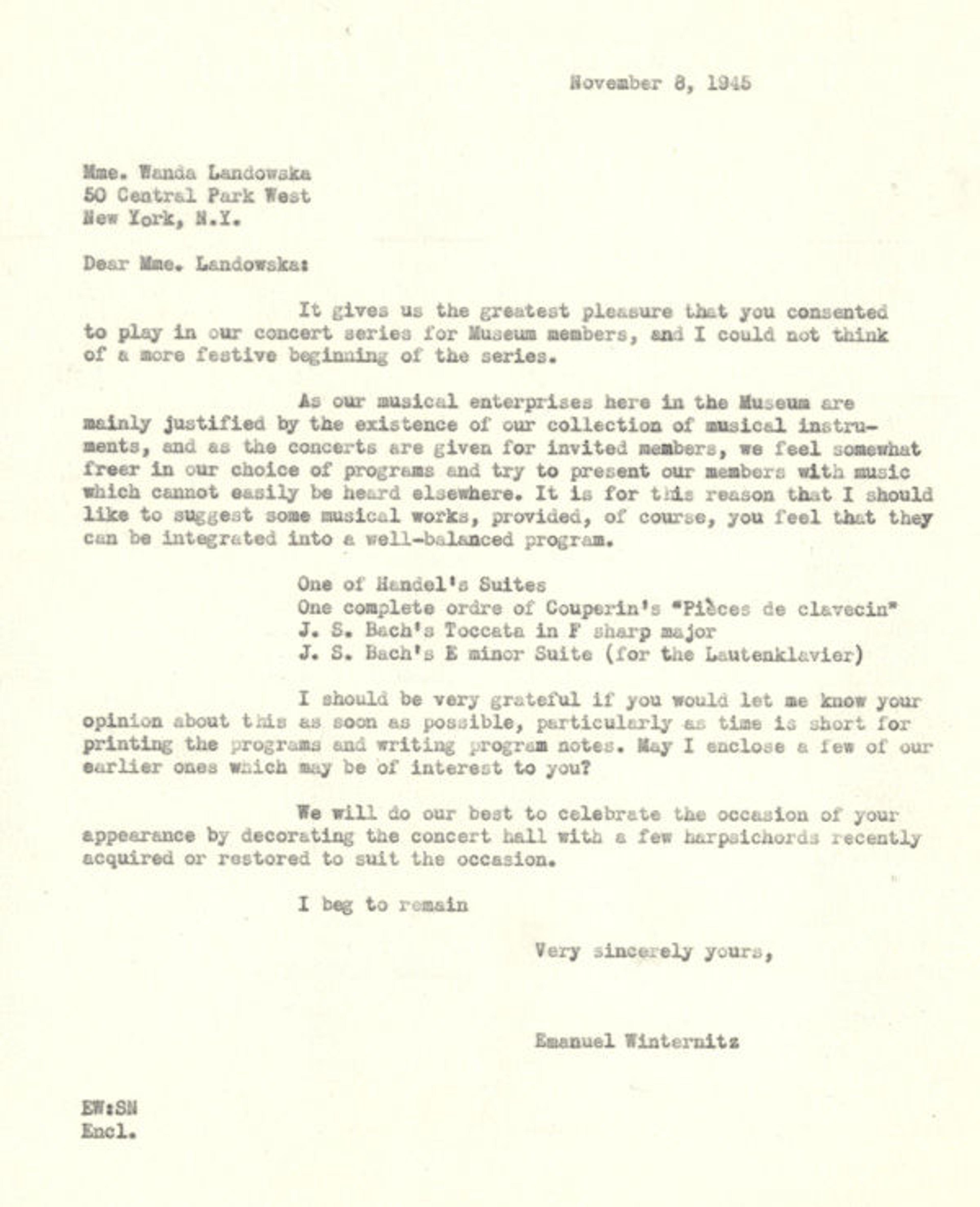

Winternitz invited Landowska to play the opening concerts of the fourth season of free Member Concerts, on December 6 and 13, 1945, for a fee of $750 for each concert; it was the first time that the Member Concerts were given twice, but capacity in the hall of the Morgan Wing, where the performances took place was only five hundred people, and Winternitz knew that Landowska would attract double that number. Landowska agreed: "I am glad to play for you and for your friends."

Winternitz described this concert in his typescript Memoirs that is located at the Museum, commenting that "from the first moment her performance revealed a great and original master, but I found it very unusual that from time to time, she removed her hands from the keyboard, folded them with elaborate dignity, and turning her eyes heavenward, pronounced sotto voce [how beautiful]." Winternitz became a good friend as well as admirer of the distinguished grande dame of the harpsichord, and it is clear that she respected him as well. His Memoirs recounts several amusing anecdotes of their relationship, including the story of a midnight call he received from Landowska, in which she insisted that he come to her apartment immediately because she had decided that her previous interpretation of the right way to play a piece by the composer Chambonnieres had been wrong for the past forty years, and she needed Winternitz to hear the new interpretation without even waiting until the next day. He duly went, and found her lying on a sofa, in white silk, "like Mme. Recamier." Once she played her new interpretation, they discussed it, and ultimately Winternitz persuaded her to make changes because he convinced her that her timing could not possibly be what the composer had intended.

Landowska performed at the Met one more time, in 1955—the year of her retirement, and more than thirty years after her first appearance—for the inauguration of the Member Subscription series in the new Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium.

Carbon of Winternitz's letter to Landowska with suggestions for her concert program, November 8, 1945. Her response is featured at the top of this post.

Related Links

Of Note: "Emanuel Winternitz and the Museum's Member Concerts" (July 27, 2015)

A Harmonious Ensemble: Musical Instruments at the Metropolitan Museum, 1884–2014, a comprehensive account of the history of the Department of Musical Instruments written by Rebecca Lindsey.