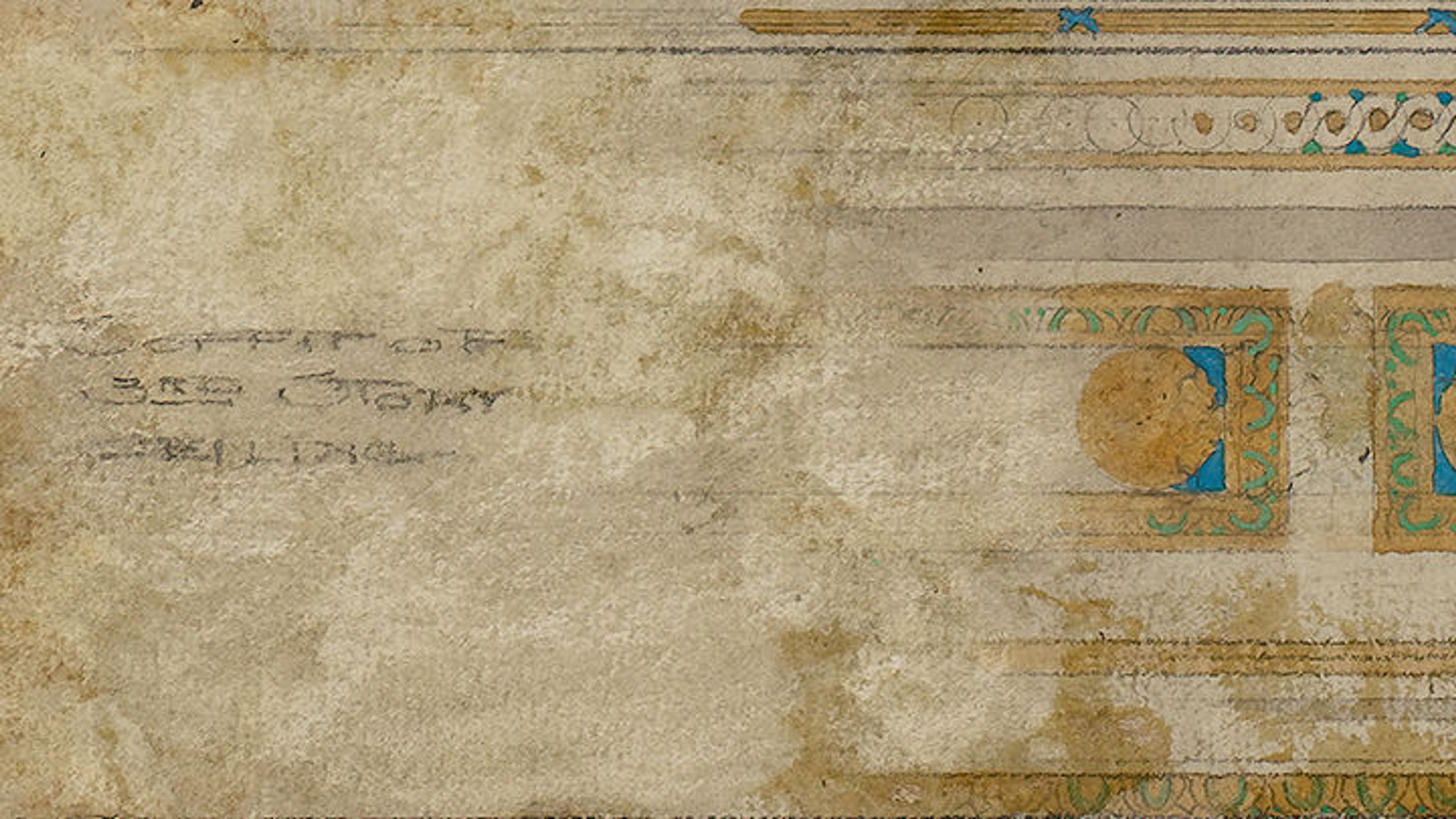

Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848–1933). Design for a rose window (detail), late 19th–early 20th century. United States, New York, possibly Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company (1892–1902). Watercolor, gouache, ink, and graphite on paper, 13 11/16 x 8 7/8 in. (34.8 x 22.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Purchase, Walter Hoving and Julia T. Weld Gifts and Dodge Fund, 1967 (67.654.97)

«The Met has in its collection a large number of design drawings from the studios of Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933). Created as in-house working documents or as presentations to clients, these drawings were rendered in watercolor on paper for the execution of works in a wide variety of projects, primarily stained glass.»

Left: Photographed before treatment. Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848–1933). Design for a baptismal font, 1902–1932. United States, New York, Tiffany Studios (1902–32). Watercolor, gouache, black ink, and graphite on artist board on pebble-finish mat board, 22 9/16 x 18 11/16 in. (57.3 x 47.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter Hoving and Julia T. Weld Gifts and Dodge Fund, 1967 (67.654.35)

When the Museum acquired these drawings in the 1960s, many had suffered mold and stains due to severe water damage. During this restoration process—a campaign that, as of today, spans more than 20 years—conservators often face dilemmas regarding the extent of intervention. For example, while it is usually the goal in conservation to avoid disturbing the original components of artworks, in extreme cases it is necessary to separate some of the layers (such as the presentation mats and backing boards) to gain access to the sheet of paper that requires treatment. The benefit of removing the mold spores is not just aesthetic; it also prevents their spread to other parts of the collection and protects the professionals who handle the art from the exposure to these dangerous pathogens. Sometimes, separating such layers brings an unexpected advantage, as when it reveals previously hidden information—a working note, a design detail extending under a mat, a name, a brush mark.

A current display in gallery 743, the Deedee Wigmore Gallery of the American Wing, offers visitors the chance to see some of these drawings with exposed elements that were intended to be concealed, and to learn how they contribute to a better understanding of design practices in the studios.

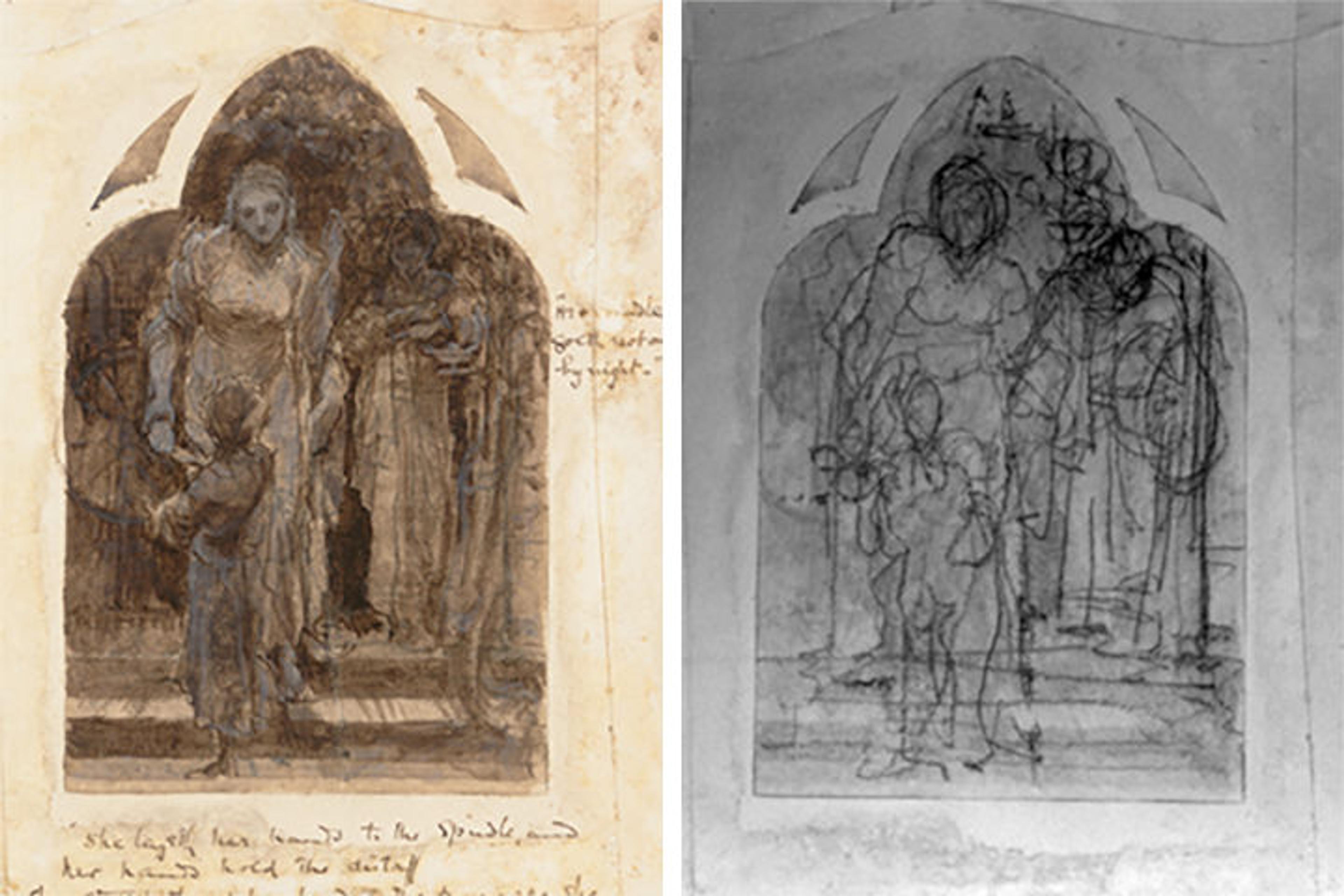

Composite image illustrates removal of presentation mat. Frederick Wilson (British, 1858–1932). Design for Dean Memorial Window, "The Virtuous Woman," First Presbyterian Church of Rutherford, New Jersey, ca. 1895. United States, New York, Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company (American, 1892–1902). Watercolor, gouache, brown ink, and graphite on paper with original mat, 14 1/16 x 21 15/16 in. (35.7 x 55.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter Hoving and Julia T. Weld Gifts and Dodge Fund, 1967 (67.654.204)

A designer for Tiffany Studios from 1893 through 1923, Frederick Wilson was aware that his designs were covered by presentation mats before they were sent to clients, so he often wrote working notes on the blank margins of watercolors. During conservation, the detachment of the original mat from this drawing permitted access to these notes and revealed an interesting detail. Faintly visible in the lower-right corner of the drawing is a graphite inscription reading, "E. W. DEAN / FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH / RUTHERFORD, NJ." This inscription incontestably links this drawing to a window in Rutherford, New Jersey, commissioned in 1895 by Mr. Edward Williams Dean in memory of his wife.

Wilson, an expert of biblical iconography, annotated each scene with quotes from Proverbs 31:10–28. Under the center design, he inscribed the verse, "She layeth her hands to the spindle, and her hands hold the distaff. She stretcheth out her hand to the poor; yea, she reacheth forth her hands to the needy." The depicted scene represents an act of charity—a mother handing out food to a hungry child. The spinning wheel to her left evokes her entrepreneurial character while a young girl stands in the background, refilling an oil lamp, an object that also speaks of industriousness.

Infrared reflectography reveals a graphite underdrawing. The lack of inscriptions on the IRR view (right) indicates the inscriptions were made with iron-gall ink, which is invisible to infrared light.

With the help of infrared reflectography (IRR), one can travel even deeper into the drawing by capturing the layer of graphite underdrawing, otherwise invisible to the naked eye. Seeing underdrawings helps us understand artists' decision-making processes and the evolution of a design. For instance, the IRR reveals that in this scene the young girl in the background did not originally hold an oil lamp, as she does in the final version. Rather, she holds a spindle while a burning candle can be seen in the apex of the arch. The verse inscribed to the right of that figure ("Her candle goeth not out by night") is evidence that Wilson changed his mind regarding the placement of the symbolic accoutrements in this biblical passage after the first draft.

Right: Composite image illustrates removal of deteriorated mat. Frederick Wilson (British, 1858–1932). Design for triple lancet window for St. John's Episcopal Church, Cornwall, New York, ca. 1926. United States, New York, Tiffany Studios (1902–32). Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper, 29 x 21 9/16 in. (73.7 x 54.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter Hoving and Julia T. Weld Gifts and Dodge Fund, 1967 (67.654.320)

In a design for a three-lancet stained-glass window, Frederick Wilson masterfully employed the translucency and brightness of watercolor to depict Saint John's vision of the holy city of New Jerusalem descending from heaven "as a bride adorned for her husband" (Revelation 21:2.).

The removal of a deteriorated mat during conservation revealed that in his initial design, Wilson had included an architectural framework surrounding the windows, which mirrored in their medieval inspiration the imaginary architecture of the Holy City represented in the center window. A small, rough sketch of an arch and battlement visible in the upper-right margin is a preliminary version of the many arches carefully rendered in the Holy City, as well as in the graphite ornaments surrounding the windows.

Frederick Wilson (British, 1858–1932). Design for triple lancet window for St. John's Episcopal Church, Cornwall, New York (detail)

The careful inclusion of the architectural elements around the window confirms Wilson's sensitive grasp of the correlation between the stained-glass window and the space for which it was intended, the Gothic-inspired interior of Saint John's Episcopal Church in Cornwall, New York.

The evocative daubs of watercolor on the margins are, in a sense, "fingerprints" that show the shape and size of the artist's brushes. They also showcase his simple five-color palette. Conveniently positioned on the edge of the paper sheet, these daubs provide a perfect source for technical analysis. Raman spectroscopy and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, conducted by the Museum scientists, determined that these colors are ultramarine, cobalt blue, vermilion, barium yellow, and an earthy brown, a selection of pigments consistent with turn-of-the-century watercolors.

Composite image illustrates removal of presentation mat. Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848–1933). Design for skylight window, 1902–32. United States, New York, Tiffany Studios (1902–32). Watercolor, gouache, ink, and graphite on artist board with original mat, 17 7/16 x 17 3/8 in. (44.3 x 44.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter Hoving and Julia T. Weld Gifts and Dodge Fund, 1967 (67.654.53)

Before conservation, it was believed this watercolor represented a mosaic panel. However, the decorated margins surrounding the main grid of this design, exposed during the treatment, revealed the details of ceiling adornments and, most importantly, the inscriptions on the margins: "SOFFIT OF 1ST AND 2ND CEILING" and "SOFFIT OF 3RD STORY CEILING." These suggest that this drawing is in fact a design for a stained-glass skylight that crowns a three-story court. The specific building for which it was created remains unknown to this day.

Removing the presentation mat revealed the inscription at left. Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848–1933). Design for skylight window (detail)

As the collection of drawings created by Tiffany's prolific firms continue to be conserved and studied, new discoveries come to light. Often, the revealed secrets unfold an entirely new line of inquiry while the answers await patiently to be uncovered.

Acknowledgment for their contributions goes to Ann Baldwin, Silvia Centeno, Alice Coney Frelinghuysen, Robyn Hoggkins, Catherine Stergar, and Denise Stockman.

Related Content

Visitors to The Met Fifth Ave can see works by Louis C. Tiffany on display in gallery 743, the Deedee Wigmore Gallery of the American Wing.

Read more about the ongoing conservation of Tiffany's design drawings in "What Lies Beneath a Tiffany Drawing?" at Now at The Met.

Kids can learn about the conservation of Tiffany drawings in "Solving a Puzzle from the Past" at the #MetKids Blog.