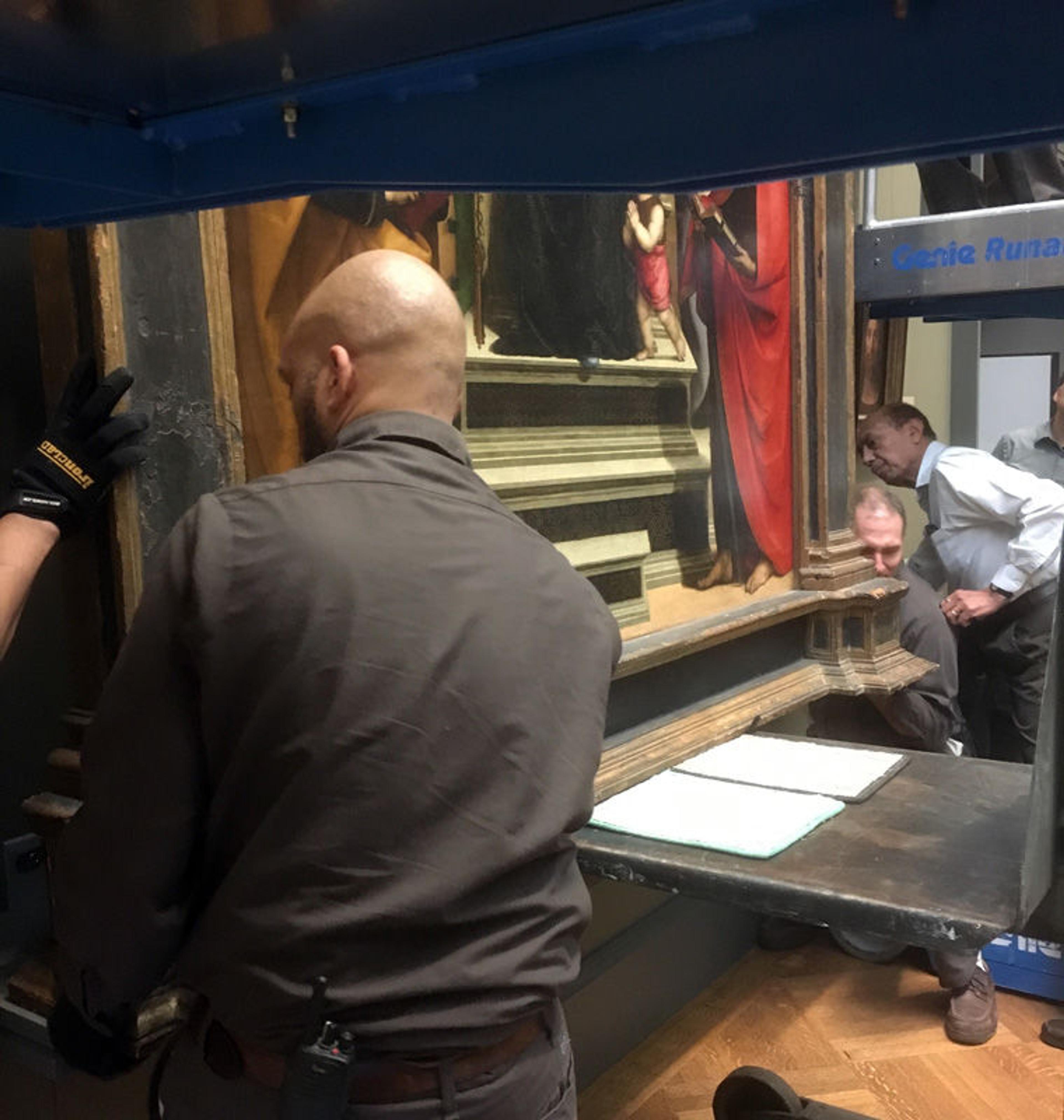

Riggers and European Paintings staff prepare to move Raphael's Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints from its former home in gallery 609. All gallery photos by the author

«The Met's Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints by Raphael (1483–1520) is the only altarpiece in America by this defining figure of Western art. The history of the work is extraordinary: Having been sold by the nuns of the convent for which it was painted—Sant' Antonio in Perugia—it belonged successively to the prestigious Colonna family (the gallery in which it hung is still one of the high points of a visit to Rome), as well as to the king of Naples and the two Sicilies. It then hung in the Louvre Museum in Paris and in the National Gallery in London before J. Pierpont Morgan purchased the work in 1901 for what was then the fabulous sum of two million French francs—a vast expenditure that made worldwide headlines. The altarpiece was gifted to The Met by Morgan following his death in 1916.»

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio or Santi) (Italian, 1483–1520). Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, ca. 1504. Oil and gold on wood, main panel overall: 67 7/8 x 67 7/8 in. (172.4 x 172.4 cm); painted surface: 66 3/4 x 66 1/2 in. (169.5 x 168.9 cm); lunette overall: 29 1/2 x 70 7/8 in. (74.9 x 180 cm); painted surface: 25 1/2 x 67 1/2 in. (64.8 x 171.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1916 (16.30ab)

All of which is to say: We don't move this landmark of The Met collection without reason! With the commencement of the Skylights Project next month and the upcoming closing of the gallery in which it had been installed, however, we had no alternative. Fortunately The Met has an amazing crew of riggers who know exactly what to do.

First, the lunette—perhaps the finest part of the altarpiece—is lifted off the main panel.

There are perks to to having to move these artworks: In this case, an up-close view of the lunette and the exquisite beauty of the figures painted by the young genius, who was barely twenty years old at the time. Perhaps ironically, the lunette is in many respects the most beautiful part of the altarpiece. In the main panel, it appears that Raphael was bound to the conservative taste of the nuns and was required to follow a conventional model that did not allow him to give full reign to the ideas percolating in his head following a trip to Florence. It's in the lunette that we see him putting into practice what he had seen and absorbed.

Then the main body of the altarpiece and its frame—secured to the wall with metal plates—are, with wonderful coordination and gentleness, slid off the supporting shelf, put onto a lift, and then transferred to a side truck for moving. It's always an impressive sight to watch the riggers team in action, choreographed to perfection.

The altarpiece is now installed in its new home for the next couple of years: gallery 962 in the Robert Lehman Wing.

This is the kind of work we will be doing over the next three months as we put highlights of the collection in galleries not affected by the first phase of the Skylights Project, so that visitors will be able to count on seeing these masterworks as much as possible. Gallery locations for works of art will be updated on the website as we progress; by July, the new installations ought to be in place so that work can begin on the skylights in the emptied galleries.

View the web feature Met Masterpieces in a New Light for more information about the Skylights Project and explore ways to engage with the Department of European Paintings' collection online.