Moretto da Brescia (Alessandro Bonvicino) (Italian, ca. 1498–1554). The Entombment (before conservation treatment), 1554. Oil on canvas, 94 1/2 x 74 1/2 in. (240 x 189.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1912 (12.61)

«How is it possible to say that we've rediscovered something that has been on the walls of The Met for more than one hundred years? It may seem odd, but that is truly the case with a grand altarpiece by the sixteenth-century north Italian painter Moretto da Brescia: The Entombment, in which the Virgin Mary and Christ's followers care for and support his body following the Crucifixion. Dated the year of his death, in 1554, the picture is a work of somber, slow-moving beauty. When the talented curator Bryson Burroughs purchased it for the Museum in 1912, he compared it to a grand piece of music by Bach or the poetry of Milton, and praised its gravity and nobility.»

By 2016, what visitors to our galleries saw instead was a diminished work of art—a victim to degraded varnish and retouching, and a failing relining. Much of the landscape and sky was practically illegible, the costumes of the figures hardly registered, and the lower portion of the canvas seemed to bulge forward. As scholars with a deep interest in this artist, we would watch, unhappily, as visitors walked past it without looking. As the Department of European Paintings prepared to close half of its galleries for the Skylights Project, we wondered how we could justify keeping this work on view among the smaller selection of our most notable works. A thorough treatment of the painting was in order.

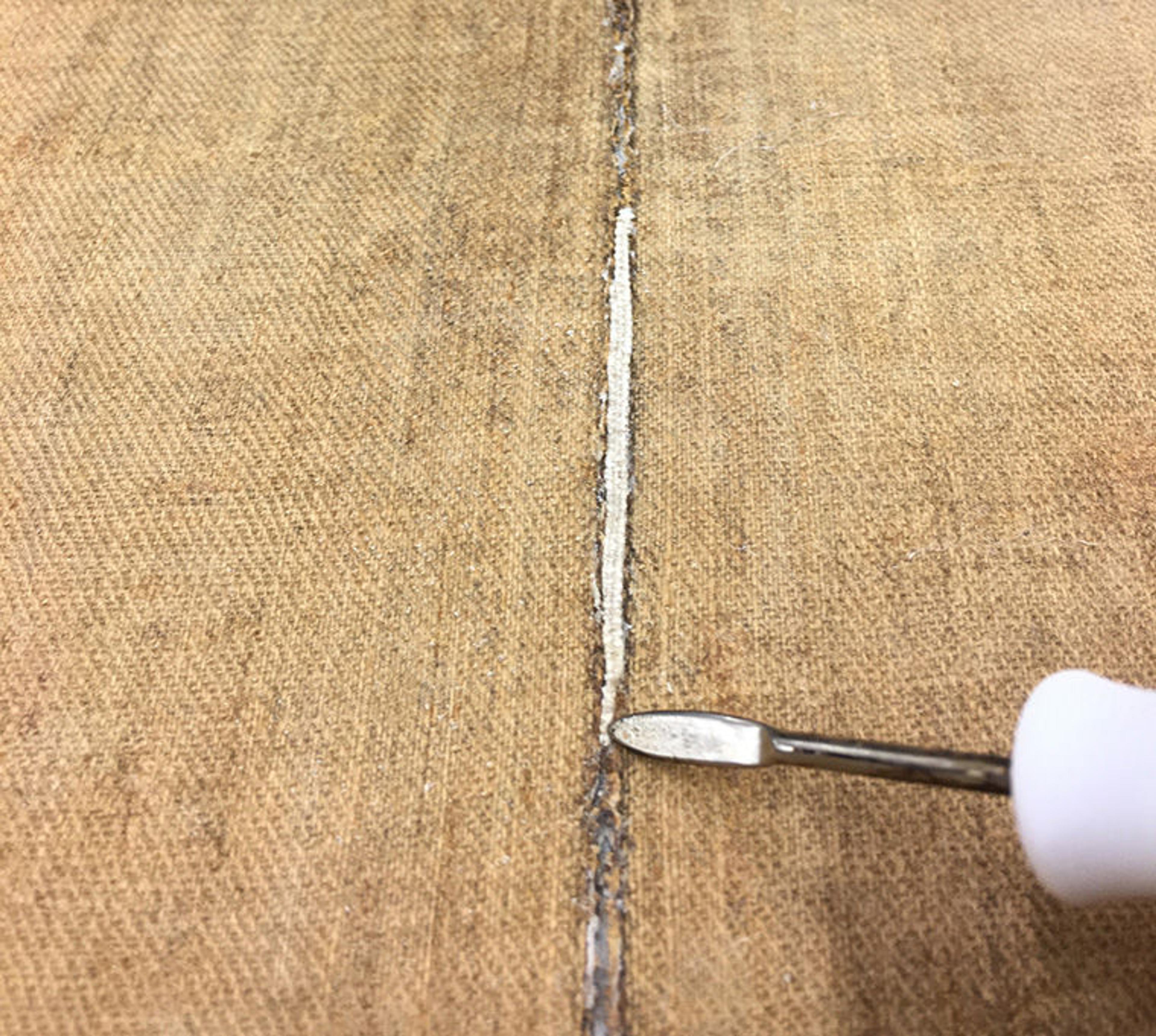

The Entombment was probably last conserved at the end of the nineteenth century, which at the time would have involved a cleaning, relining (the attachment of an additional canvas on the reverse), and restoration (compensation for paint losses by means of retouching). More than one hundred years later, that intervention was showing serious signs of its age. The varnish was murky and discolored, the retouching appeared dark and blotchy, and the lining was no longer holding the painting in plane, so that the original seams—the canvas is composed of several pieces—were prominent and unsightly. Frankly, the painting looked neglected and its appearance implied that this was a second-rate work, and therefore not worthy of our attention. It was time to change that, and in October 2016 the painting was brought to the Department of Paintings Conservation's studio so that a full treatment of the work could commence.

Detail view of The Entombment before conservation treatment. The dark patches on Saint John's drapery are old discolored retouchings.

For more than ten years, we had hoped to conserve this magnificent painting, since its grandeur and impact was so clearly undermined by its current condition. Yet from the outset, it was clear that this would be a major undertaking, and it frequently feels as though there is never a good time to begin such a complicated project. However, the thoughtful rehanging of the European Paintings galleries for the Skylights Project created the right impetus to finally "bite the bullet," so to speak!

The first step, after the usual process of documentation, was to remove the varnish and old retouching using appropriate solvents and solvent gels.

Left: Discolored varnish is removed from Christ's loincloth. Center: Old darkened retouching from previous treatments is removed from Christ's loincloth. Right: The loincloth after removal of varnish and retouching, a process that revealed paint losses to the original.

After that, the tedious and time-consuming removal of the old lining was undertaken. The painting was laid face down, removed from its stretcher, and the lining canvas was separated from the reverse of the original canvas. The lining canvas was so acidic and brittle that this could only be done an inch or two at a time.

Left: The canvas's brittle lining is eased away from the original. Right: A collection of shreds of the old, very acidic lining fabric. Much of the adhesive remains on the reverse of the original canvas.

Then followed the even more tedious process of carefully scraping away the desiccated remains of the lining adhesive. This all took several weeks in total.

The residues of the old lining adhesive are carefully scraped away.

The seams were then repaired and the whole painting was attached to a new linen canvas using a heat-seal adhesive, which does not penetrate the painting and will be easily reversible in the future.

New canvas is inserted in order to repair the original seams.

Conservators Michael Gallagher and Charlotte Hale restretch the painting following lining.

The Entombment after cleaning and relining, but before retouching. The paint losses are generally associated with the original seams but also where the painting was most likely adversely affected by dampness in the past, causing the paint to flake (most prominently in the bottom left of the picture).

The painting was restretched, a thin isolating layer of varnish applied, and the paint losses were filled and retouched. While this sentence was easy to write, it represents many months of detailed work! A final saturating varnish was applied and Moretto's magnificent painting was ready to return to its proper place—on prominent public display in the galleries.

View The Entombment before and after recent conservation treatment by moving the slider across the image.

We can now understand Moretto's original intent as he builds the contrast between the grim, suffering faces of the Virgin and Mary Magdalene, and the slowly lightening sky—a lemony yellow light moving across from the left and touching rocks and clouds.

Detail of the sky in the upper left corner of The Entombment (after conservation treatment)

The scene suggests that there is hope for the future, for a new day, alongside the profound sense of grief. And nothing could be more brilliant than the colors of the garments of the figures who cluster around Christ: the purple of a turban, the shimmery gold and yellow/green of robes, ermine fur, and varying deep reds. They too suggest the triumph of faith over death.

Charles Eastlake, the first director of London's National Gallery, shared our enthusiasm for this painting. He almost bought it for the National Gallery in 1862, but in the end was dissuaded by a detail that he found indecorous: the way in which the Virgin touches Christ's abdomen. He could not get his mind around this gesture, and finally declared the work "ineligible" for the collection. It is very interesting in the history of taste that this Victorian sensibility now seems from the distant past—and what a good outcome it was for the The Met!

Detail of the Virgin's hand on Christ's abdomen (after conservation treatment)

We are fortunate enough to have a grand frame for this painting that was made in Lombardy at about the same time. Frame historian Timothy Newbery notes that after a long period in which Lombard altarpieces were framed by elaborate columns based on classical Roman ornament, this quieter, shallower frame is characteristic of its moment, more in keeping with the sober message of the work itself. The dark walnut tone—inspired by interiors of rooms in northern Italy—set against the gilt moldings provide an ideal surrounding for the painting.

Left: The Entombment installed in gallery 638 in its new frame

Be sure to visit this painting in gallery 638, where it hangs alongside other major works by sixteenth-century Italian artists, from Andrea del Sarto to Veronese. It is particularly meaningful to see Moretto's altarpiece, so important as a statement of Catholic devotion, between two remarkable portraits of contemporary ecclesiastics—one by Titian and the other by Lorenzo Lotto.

Related Content

View the web feature Met Masterpieces in a New Light for more information about the Skylights Project and explore ways to engage with the Department of European Paintings' collection online.

Read more articles in this Collection Insights blog series.

Read essays related to this topic on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Sixteenth-Century Painting in Lombardy"; "The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting."

In an episode of The Art Newspaper Podcast, Andrea Bayer and Michael Gallagher discuss the conservation treatment of this work with Art Newspaper Features Editor Ben Luke.