Detail views of four fifteenth-century works from Italy and France depicting the Crucifixion and Entombment of Christ. Left to right: Stefano da Verona's The Crucifixion; Jacopino da Tradate's Crucifixion, from The Ancona of the Passion; Michelino da Besozzo's Christ Entombed; The Limbourg Brothers' Descent from the Cross, from The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry

Sometimes our view of the past differs in significant, even totally divergent ways from those who lived at the time in question. For instance, we assume that almost everything of significance in fifteenth-century art had its origins in Florence, Venice, or Bruges. Yet a case can be made that in the early fifteenth century the most cosmopolitan center in Italy was neither Florence nor Venice—it was Milan.

As evidence, we have a notice written about 1420 by the outstanding scholar Uberto Dicembrio, who held the post of secretary to the Duke of Milan, Giangaleazzo Visconti. He was well informed, and from his vantage point the three outstanding painters of his day were: Michelino da Besozzo, a local artist; Gentile da Fabriano, a painter from the region of the Marches in northern Italy; and Jean d'Arbois, a French painter. All were active at the court of Milan, which had attained a European sophistication under Giangaleazzo.

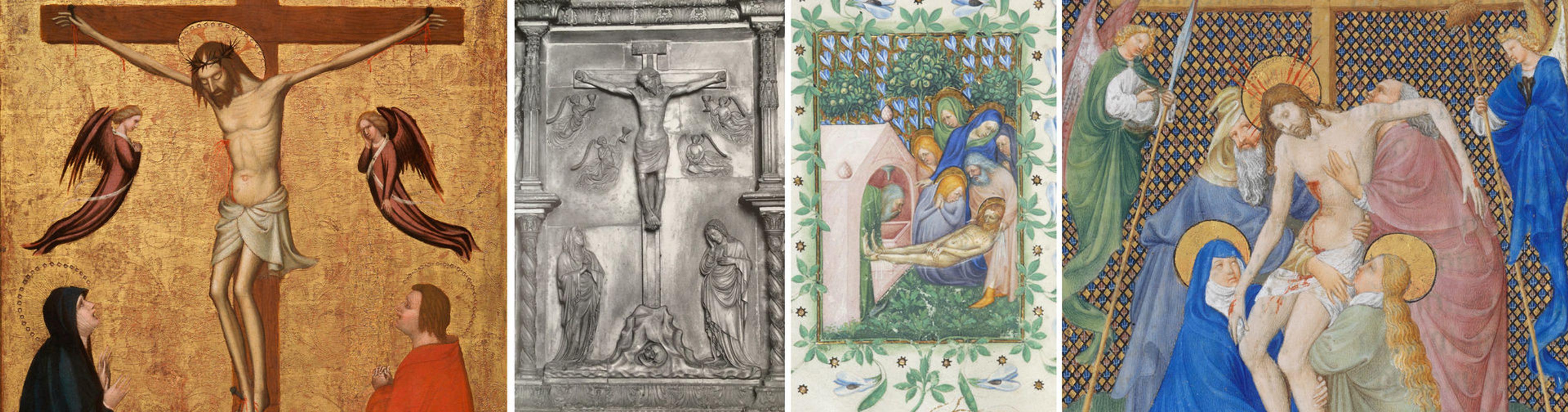

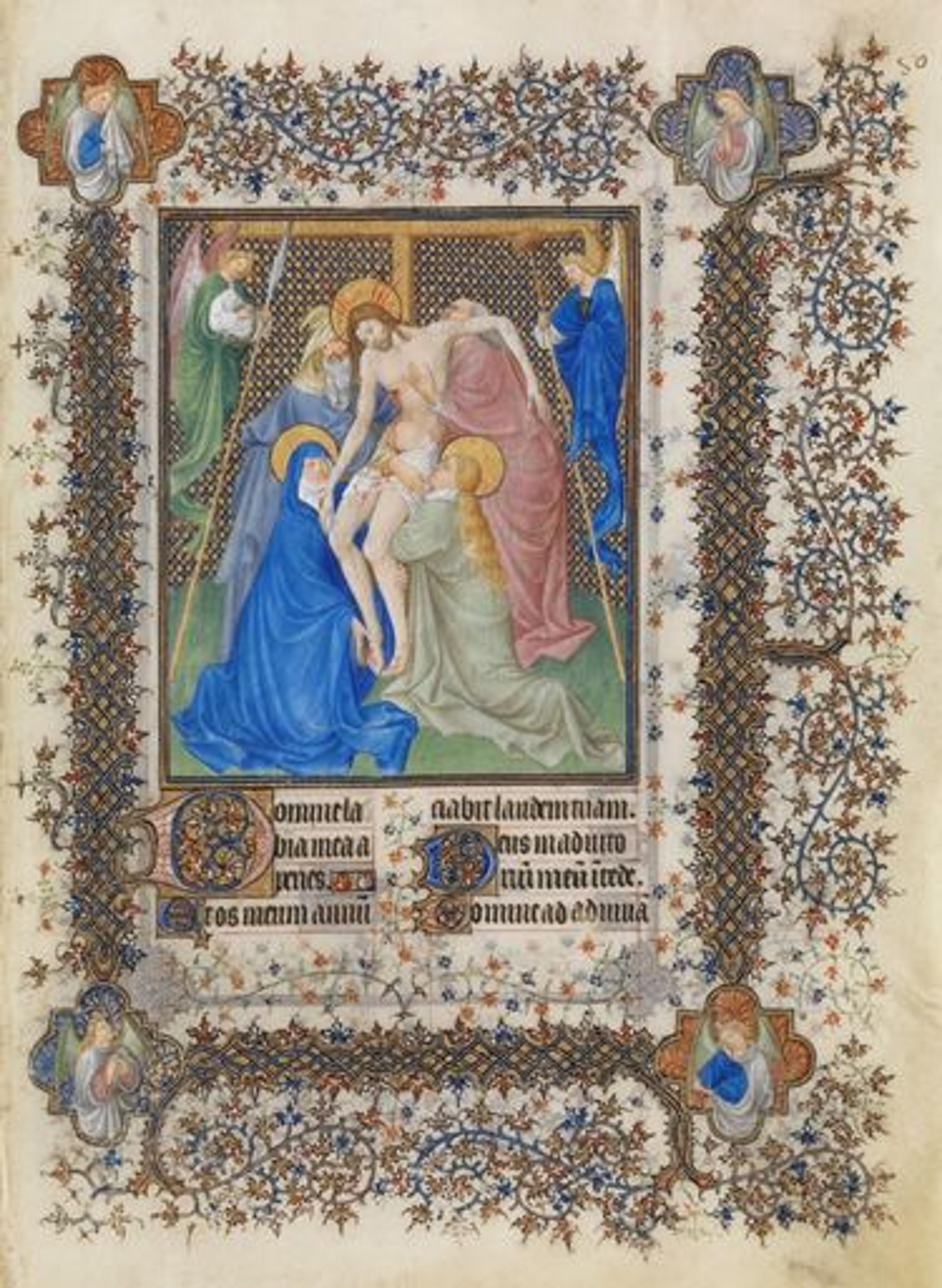

Talk about a completely different point of view from our Tuscan-biased one! Only one of these artists, Gentile da Fabriano, has achieved some fame today, due to the fact that his finest work, an altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi, is in the Uffizi in Florence and makes a perennial appearance on Christmas cards. Michelino, whose fame in his day was simply enormous, is today known only to specialists, though The Met is fortunate to own a picture by him (alas, not one in good condition), and an exquisite manuscript containing his illuminations is in the collection of the Morgan Library & Museum. The miniatures in that prayer book give a clear idea of his individual, even eccentric imagination, as well as of his mastery in painting flowers and animals.

Left: Michelino (de' Molinari) da Besozzo (Italian, ca. 1370–ca. 1455). Christ Entombed, folio 24v from a prayer book, ca. 1430. Ninety-five leaves (one column, 15 lines), bound: vellum, ill.; 170 x 120 mm. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Purchased with the generous assistance of Alice Tully in memory of Dr. Edward Graeffe, 1970 (MS M.944)

What about Jean d'Arbois? He's the one that has interested me over the past several months, since he was the father of Stefano da Verona, the artist who painted The Met's newly acquired Crucifixion scene. The plain truth, unfortunately, is that we just don't know much; there is not a single documented work by him.

What we do know, however, is that he worked in Paris and Dijon for the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold, as well as in Milan for Giangaleazzo. The two were brothers-in-law, as Giangaleazzo had married Philip's sister, Isabella of France, and communication between their courts was frequent. Indeed, Giangaleazzo's daughter, Valentina, married Louis d'Orleans, the nephew of Philip the Bold. In other words, Jean d'Arbois was a truly cosmopolitan artist working at a clearly Francophile court. (In Italy, he was known as Giovanni d'Arbosio di Francia, since he was French by birth—as presumably was his son Stefano.)

Although there have been a number of attempts to identify paintings from his hand, the matter remains no more than conjecture. Yet it is to him that Stefano doubtless owed his initial training, and we seem to see in his work echoes of the elegance of French miniature painting.

Stefano da Verona (Stefano di Giovanni d'Arbosio di Francia) (Italian, ca. 1374/75–after 1438). The Crucifixion, ca. 1400. Tempera on wood, gold ground, 33 7/8 x 20 5/8 in. (86 x 52.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Álvaro Saieh Bendeck Gift; Gwynne Andrews Fund; Charles and Jessie Price Gift; Philippe de Montebello Fund; Gift of Mrs. William M. Haupt, from the collection of Mrs. James B. Haggin, Bequest of Lillian S. Timken, and Gift of Forsyth Wickes, by exchange; Victor Wilbour Memorial Fund; funds from various donors and Gifts of the Marquis de La Bégassière and Cornelius Vanderbilt, by exchange; Marquand Fund; and The Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Fund, 2018 (2018.87)

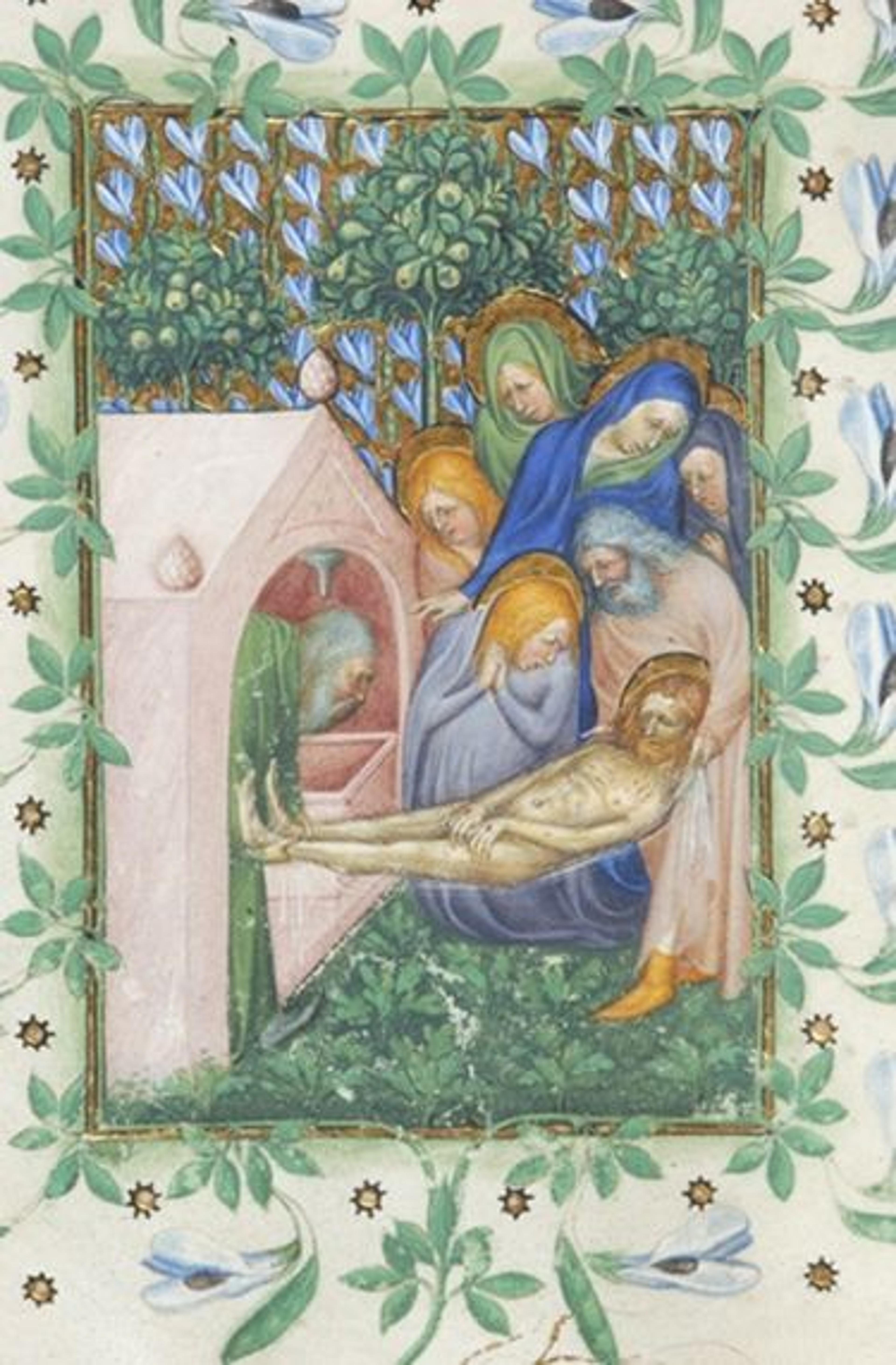

When I had the opportunity to study Stefano's Crucifixion for the first time, I felt the presence of a hyper-elegance that I associate with French miniature painting. There is the elongation of the bodies, the conspicuously eloquent gestures, the sweep of drapery around the Magdalene's feet, and the extraordinary refinement of the tooling of the gold background with a pattern of stems of roses.

Right: The Limbourg Brothers (Franco-Netherlandish, active France, by 1399–1416). Descent from the Cross, folio 80r from The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–1408/1409. Made in Paris, France. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, single leaf, overall: 9 3/8 x 6 11/16 in. (23.8 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1a, b)

I was reminded of the features one finds in the work of some of the key figures of French miniature painting of the early fifteenth century, such as the so-called Boucicaut Master (who may, in fact, have worked in Italy), and the truly great Limbourg Brothers, as dazzlingly represented in the book of hours at The Met Cloisters, illuminated for the Duke of Berry—the brother of Philip the Bold and brother-in-law of Giangaleazzo—around 1405–1408/9.

Where Stefano reveals his Italian grounding in his Crucifixion is in the austerity of the composition, with its insistence on rigorous symmetry, and in the harsh, plebian features of the figure of Christ. For this, the closest analogies we can make must be drawn from sculpture and the international group of artists Giangaleazzo assembled to decorate the Cathedral of Milan and the Basilica of Sant'Eustorgio, which were then under construction.

Left: Jacopino da Tradate (Italian, ca. 1371–1445). Crucifixion (detail from The Ancona of the Passion), ca. 1410. Basilica of Sant'Eustorgio, Milan

And there we are: As a reminder that what we don't know is sometimes at least as interesting and important as what we think we know, the context for The Met's Crucifixion picture is one of the most fascinating but still nebulous chapters in the history of Italian painting.

Related Content

Read essays related to this topic on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "The Book of Hours: A Medieval Bestseller"; "Manuscript Illumination in Italy, 1400–1600."