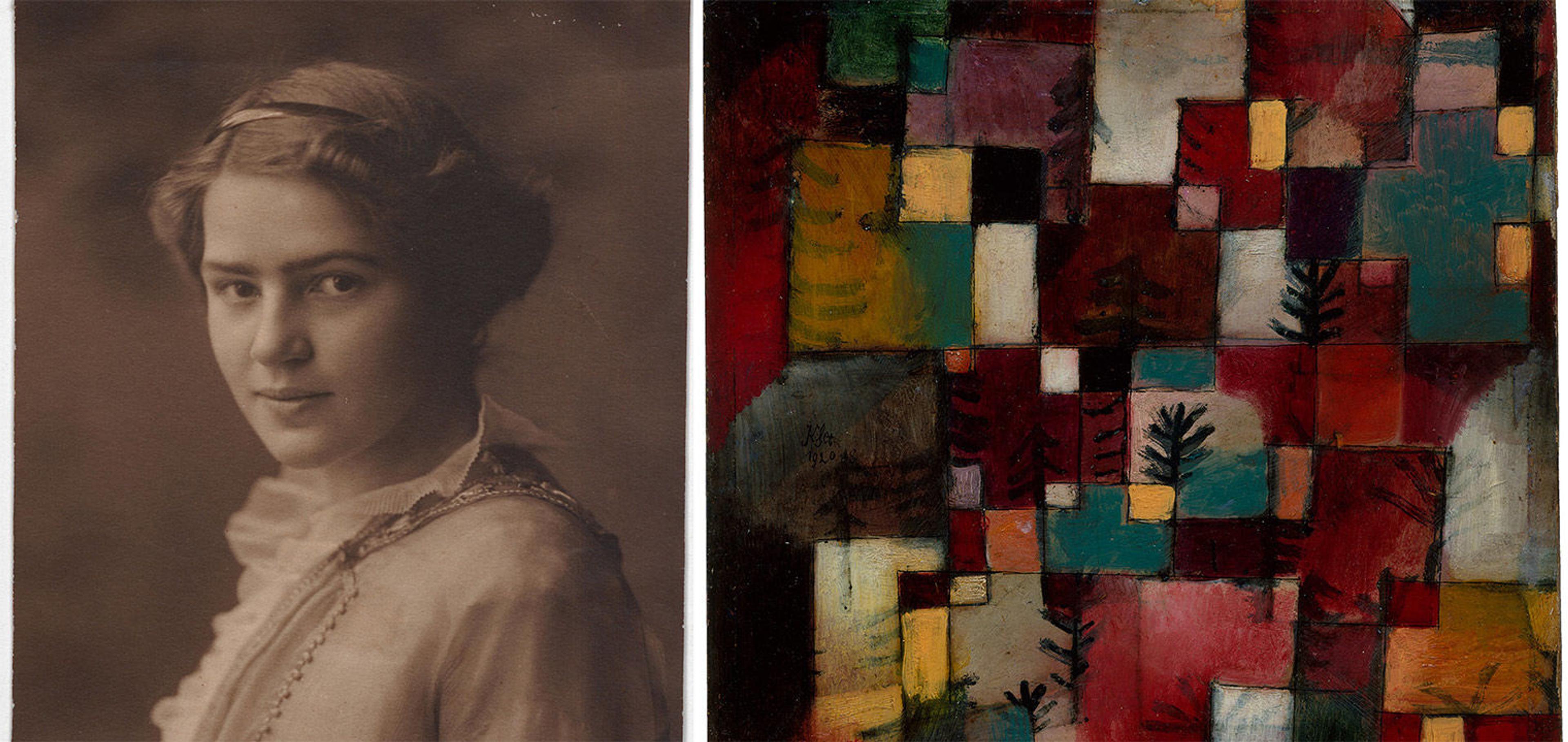

Friedrich Müller. Portrait of Sophie Schneider [Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers] as a young woman, 1914. Photograph, brome-silver gelatin print, 13.7 x 9.8 cm. Inv. D 9592. On loan from the Kestnergesellschaft. Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Germany. Photo Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Sprengel Museum / Friedrich Müller / Art Resource, NY

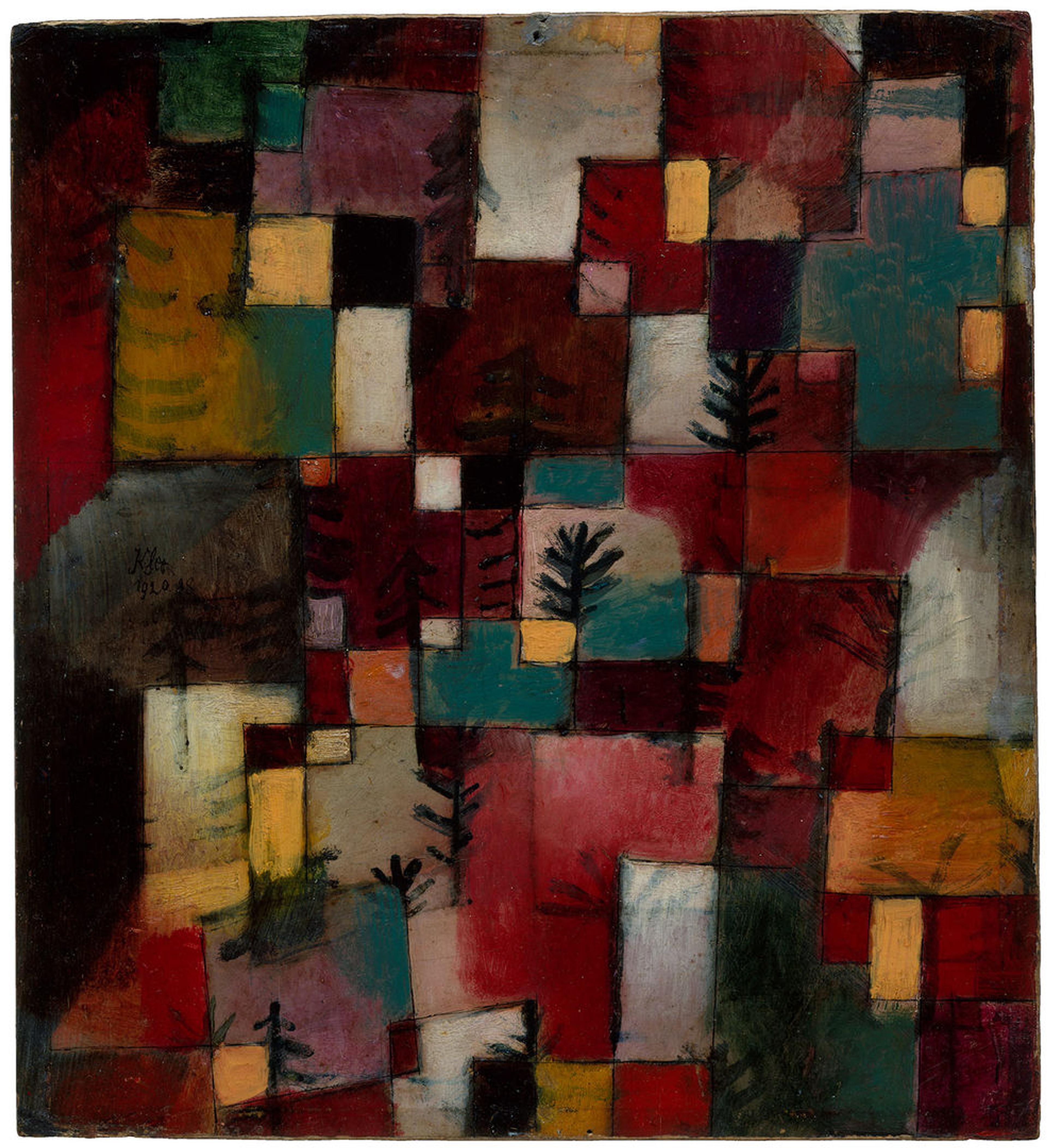

In 1920, Paul Klee recorded a small oil painting on cardboard in his inventory book: Cubist Construction (with cobalt violet cross) (Kubischer Aufbau [mit kobaltviolettem Kreuz]). In May and June of that year, the artist exhibited this composition of overlapping rectangular planes interspersed with tiny fir trees in a one-man show at his dealer's, the Galerie Neue Kunst Hans Goltz, Munich. The painting was listed in the exhibition catalogue as Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms (Rotgrüne und violettgelbe Rhythmen).

The small painting was subsequently owned by Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers. A name like Sophie's can alert us to problems with the provenance (ownership history) of a work of art, since her collection was looted by the Nazis while it was on loan to a German museum. But the presence of a red-flag name does not always connote a troubling gap in a work's provenance. This is the story of how Sophie's painting escaped Nazi looting and came to The Met.

Paul Klee (German, b. Switzerland, 1879–1940). Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms, 1920. Oil and ink on cardboard, 14 3/4 x 13 1/4 in. (37.5 x 33.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984 (1984.315.19)

According to his inventory, Klee sold the painting to his dealer, Hans Goltz in April 1921, about a year after it was first exhibited. Goltz most likely sold the painting directly to its next owner, Paul Erich Küppers, who was the first director of the Kestner Society (Kestner-Gesellschaft), an institution established to introduce new, innovative artists in the city of Hannover. Paul Küppers had met Sophie, his wife, when they were both students of art history at the university. Both were prominent collectors and champions of contemporary avant-garde artists. Following her husband's untimely death during the Spanish flu epidemic of 1922, Sophie supported their two young sons by organizing exhibitions of decorative arts in the Kestner-Gesellschaft building, occasionally selling works from her private collection. She met the Russian artist El Lissitzky later that year, when he was in Hannover for a Dada concert arranged by Kurt Schwitters.

El (Eleazar) Lissitzky (1890–1941) © ARS, NY. Kabinett der Abstrakten (Abstract Cabinet, room in the Provinzialmuseum, Hannover, with works by Piet Mondrian and others, 1928/29). State 1928. Exhibition space fitted with (in part) moveable wall constructions, steel lamella, rotatable glass showcases, fabric covering. Destroyed. Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Germany. Photo Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Sprengel Museum / Art Resource, NY

An artistic and personal collaboration developed, leading to Sophie's decision to move to Moscow to join Lissitzky. Before leaving Germany, in August 1926, she lent sixteen artworks from her collection to the Provincial Museum in Hannover, under the care of its director, Dr. Alexander Dorner. Among these was the small Klee painting on cardboard, Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms. At the director's request, Lissitzky would start work on designs for the Provincial Museum's gallery of modern art (Kabinett der Abstrakten) that fall (above).

In January 1927, the couple reunited in Moscow, where they soon married. But plans for exhibitions in Dresden and Leipzig brought them back to Germany in 1930. While in Hannover, Lissitzky retrieved three of the artworks his wife had lent to the Provincial Museum before moving to Moscow, as evidenced by a receipt in the museum's archives: a watercolor by Fernand Léger; a Klee watercolor, Comet over Paris; and the painting Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms. The whereabouts of the Léger cannot be tracked from this point on, but we do know that the two Klees were brought to Moscow.

That same year, Sophie (now Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers) gave birth to a son, Jen Lissitzky, and her two sons from the first marriage joined the family in Russia. Lissitzky received commissions from the Soviet government, designing exhibitions, magazines, and books using innovative typographical and photo collage techniques. His projects were increasingly realized with the aid of his wife, because of his years-long suffering from tuberculosis, an illness that led to his death in 1941.

Jen Lissitzky. Photograph of Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers in Novosibirsk, 1978

In 1944, three years after Lissitzky's death, Sophie was deported as an enemy alien to Novosibirsk, Siberia, along with her son Jen. During the chaos of packing for the move, the Klee watercolor, Comet over Paris, went missing. Isolated and impoverished in Siberia, she made ends meet by teaching crafts and needlework to children. Her granddaughter, Olga, later recalled often eating at a small table before the sofa, and her grandmother's habit of sweeping up the crumbs afterwards onto a small painted board, presumably one used in her lessons. Both Olga and Jen identified this board as Klee's Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms.[1]

Although her exile officially ended in 1956, Sophie stayed in Siberia. She made only one trip outside of Russia, in 1958, when she brought the Klee painting to Austria and sold it to the collector Carlo Kos. In correspondence with Sabine Rewald, now Jacques and Natasha Gelman Curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met, Kos described his purchase from Lissitzky-Küppers and his subsequent sale of the painting at Sotheby's, London, in July 1974. The Acquavella Galleries, New York, acquired it from the Sotheby's auction, and shortly thereafter the painting entered the collection of Heinz Berggruen. In 1984, it became part of The Met's renowned Klee collection, as a gift of Berggruen.

The thirteen works from Sophie's collection that had remained in the museum at Hannover—including three additional Klees—met with far different fates. All were seized from the Provincial Museum by the Nazis in 1937 and branded as "degenerate art."

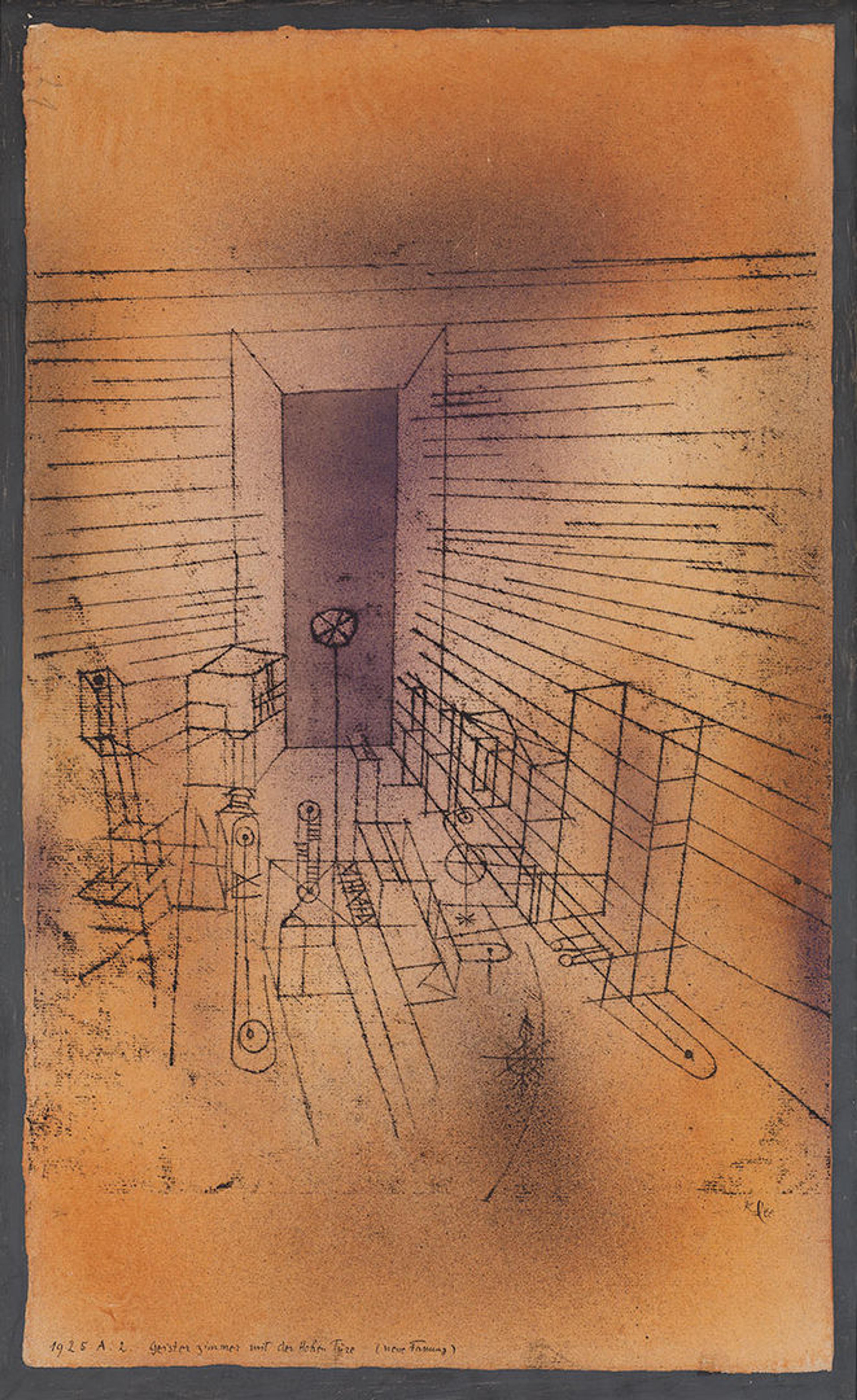

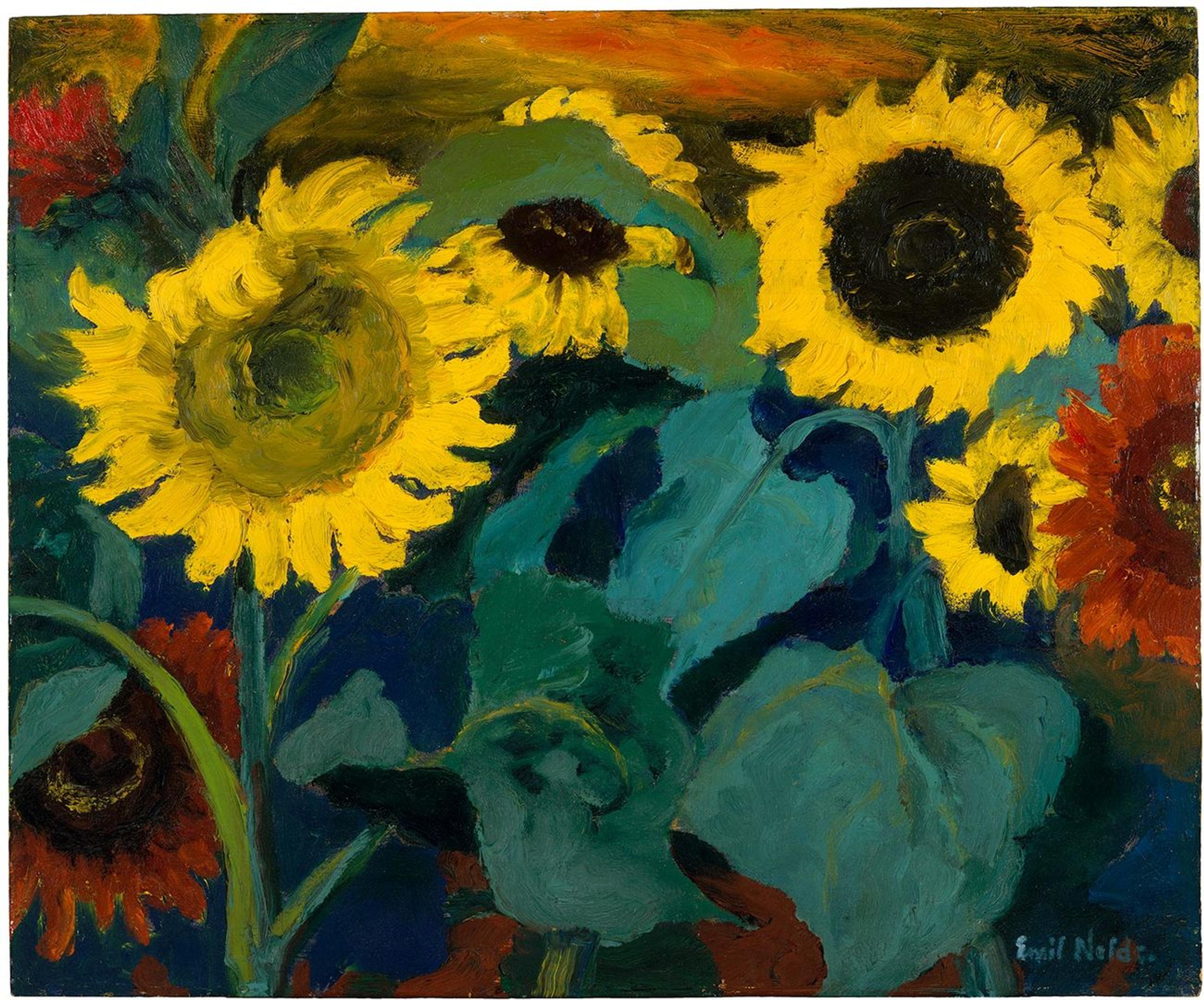

Left: Paul Klee (German, b. Switzerland, 1879–1940). Ghost Chamber with the Tall Door (New Version). 1925. Sprayed and brushed watercolor, and transferred printing ink on paper bordered with gouache and ink, mounted on cardboard, 24 x 16 5/8 in. (61 x 42.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1987 (1987.455.16). Right: Emil Nolde (German, 1867–1956). Large Sunflowers, 1928. Oil on wood, 28 7/8 x 34 7/8 in. (73.3 x 88.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Walter J. Reinemann, 1970 (1970.213)

One of the Klee paintings, Swamp Legend, was shown in the notorious "Degenerate Art" exhibition that was held in several German venues from 1937 to 1938, as was another Klee, Ghost Chamber with the Tall Door (New Version), now also in The Met collection (above). Several of Sophie's works were eventually sold through the dealers Ferdinand Möller, Hildebrand Gurlitt, and Karl Buchholz, and made their way to private collectors or museums. Still others cannot be traced.

Because all of these thirteen works were privately owned by Sophie, even though they were physically located at a German museum, her heirs have been able to receive compensation or restitution for four works, including Swamp Legend as recently as 2017. There existed a precedent during the Nazi regime for such restitution of works belonging to non-Jewish collectors that had been seized while on loan to German museums. For example, Emil Nolde had lent his painting Large Sunflowers to the Museum Folkwang in Essen, where it was confiscated in 1937 and consigned for sale in 1939 to Karl Buchholz in Berlin. Nolde successfully retrieved it in 1939, and it is now owned by The Met (below).

Emil Nolde (German, 1867–1956). Large Sunflowers, 1928. Oil on wood. 28 7/8 x 34 7/8 in. (73.3 x 88.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Walter J. Reinemann, 1970 (1970.213)

Works seized from the holdings of state-run German museums, on the other hand, are not legally bound to be returned to those museums. Such is the case with three Klees in The Met collection: Ghost Chamber with the Tall Door(above); Cold City; and Classical Grotesque, which were formerly owned by the Museum Folkwang Essen, Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim, and Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, Frankfurt, respectively.

The story of how Klee's Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms came to The Met thus involves more than one narrow escape. The first came when El Lissitzky decided to remove the painting from the Provincial Museum in Hannover, thereby preventing it from being stolen by the Nazis. The second was when it journeyed with him to Moscow. And the third came years later, when the painting accompanied Sophie on her forced move to Siberia.

The early history of this painting thus serves as witness to the remarkable life of Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, who, through ambition and necessity, established her own livelihood as an art dealer, creative partner, and teacher. In the end, Redgreen and Violet-Yellow Rhythms played a role in her economic survival through its sale in 1958—the only legitimate sale, by its owner, of any work from among the sixteen works that she lent to the Provincial Museum in 1926.

Note

[1] Ingeborg Prior, Die geraubten Bilder: Die abenteuerliche Geschichte der Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers und ihrer Kunstsammlung (Cologne: Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2002), 188–89.

Provenance Research Resources

A portal to historical documents and provenance research projects at The Met, across the United States, and abroad.