At fourteen, while my straight peers were experiencing their sexual awakenings over adult magazines and posters of boybands, I was fantasizing about Diana the Huntress. The most common sculptural interpretations of the goddess—found in countless museums and typified by Edward Francis McCartan’s 1923 bronze, or Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s, which once stood atop the tower of Madison Square Garden—depict a lithe huntress, tall and pert-bosomed, accompanied by a dog or stag, a drawn bow or spear in her hand, squinting at some distant prey. Like many of my adolescent idols, I equally wanted to be her and bed her.

Left: Edward Francis McCartan (American, 1879–1947). Diana, 1923. Bronze, gilt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1923 (23.106.1). Right: Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, 1848–1907). Diana, 1893–94. Bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1985 (1985.353)

Never mind that she was supposedly celibate; she would be a skilled lover—with firm hands and flashing eyes that you’d be smart to fear a little, even as the object of her affection. A god’s desire was a dangerous thing to court; anyone who has even dabbled in Greek and Roman myths knows that. Invidia—the god of jealousy and revenge—is the companion of Venus, and no more evident than in the affairs of other deities. Then, of course, there is all the rape—a violence that is sometimes ambiguously interchanged with seduction in classical representations of mythology.

Still, I loved the passionate travails of the gods, so human in their emotions. Sensitive and passionate, beset by chronic limerence, I was ruled by Venus, but as an eldest daughter who had attended my younger brother’s birth, I saw myself in Diana. Most stories told of firstborn Diana serving as midwife to her mother Latona and delivering her twin brother Apollo. As a child, she asked her wandering father Jupiter to grant her ten wishes, among them to rule all the mountains, to wear a knee-length tunic in order to hunt comfortably, to be the Phaesporia or Light Bringer, and to always remain a virgin.

Unlike most virginities, Diana’s does not signify purity so much as power. Her celibacy is no deprivation but instead the condition that facilitates her status as an equal to the male gods. Every man who thinks of raping her or sees her bathing or claims to be a superior hunter to her is struck down; transmogrified into an animal; killed by animals; or turned into constellations, stone, or girls. Nor is she characterized as asexual so much as abstinent of the rituals that symbolically and socially signified her subservience to men. Even the gods suffered under patriarchy, and like many women across world history, Diana recognized the value of opting out.

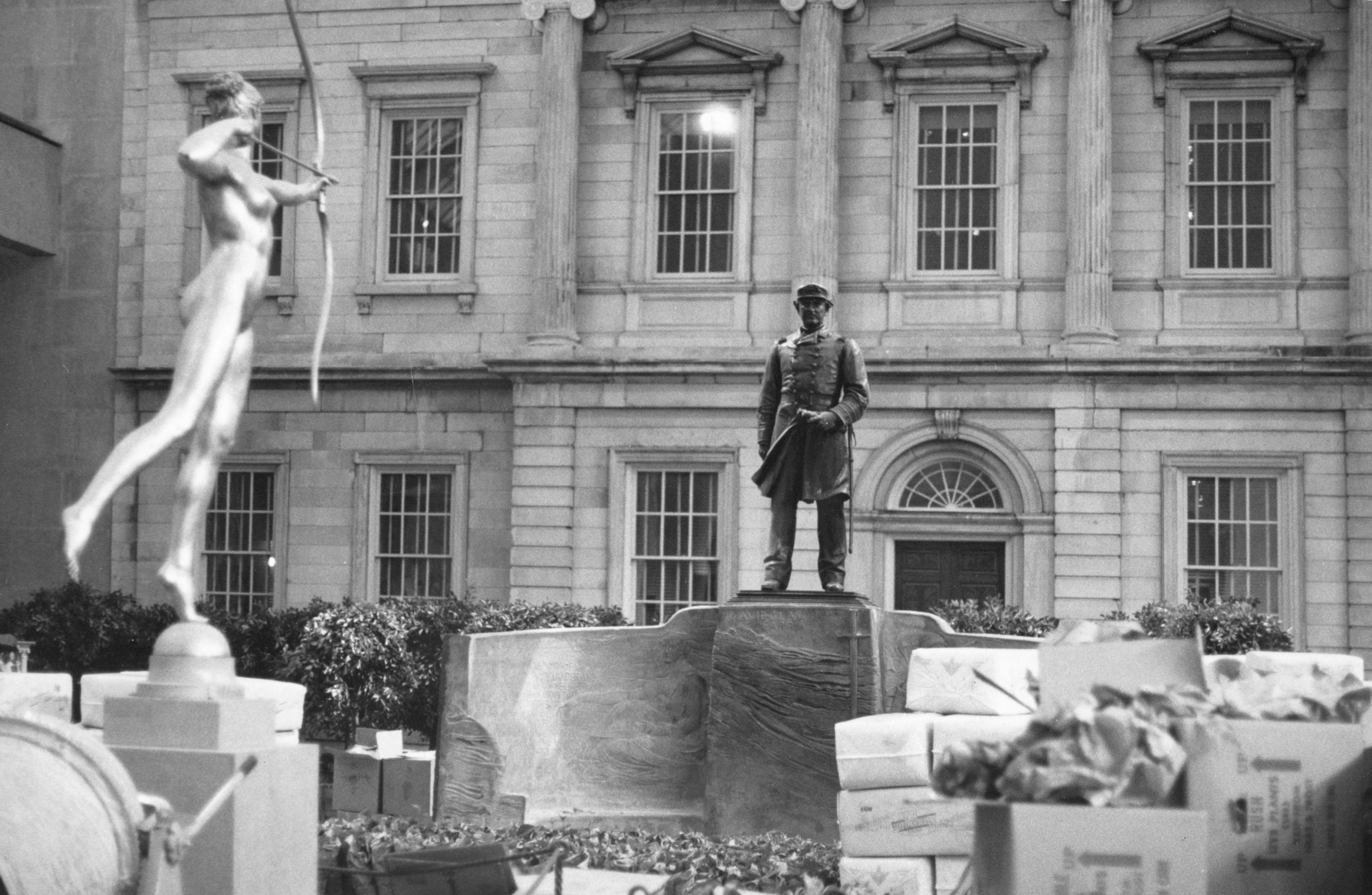

View of Diana (1893–94) in The Met’s Engelhard Court as part of the 1985–86 exhibition Augustus Saint-Gaudens: Master Sculptor.

As my wife, a poet, put it: “Athena and all those male gods are like, ‘We have to go to war and defend our patriarchal hierarchy!’ And Diana is all, ‘Hmm, oh, we have a boar hunt this weekend. I really wish I could come, but these boars won’t kill themselves.’”

The clincher for me was the pack of beautiful hounds gifted to her by Faunus. My love for Diana was erotic, sure—I would have joined her merry band of virgins in a heartbeat—but it was also aspirational: I wanted to be that commanding huntress, to live among a fleet of adoring nymphs and hounds and transform any man who crossed me.

As a queer adolescent in a small-town in the pre-internet 1990s, it was difficult to find my people, or many images of actual lesbians. I pored over my mother’s worn copy of Our Bodies, Our Selves (1976), memorized Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) by Rita Mae Brown, and eventually found Alison Bechdel’s comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, but portrayals of women in erotic communion with each other (outside of media designed for the straight male gaze) were elusive. Some of the earliest such images I encountered were paintings of the goddess Diana. My fingers remember the tactile sensation of flipping through the thick, glossy pages of art books at the school or public libraries, drawn particularly to paintings of Diana that imagined her among her cohort of virgin nymphs. They are frequently represented bathing or in luxurious quiescence, semi-clothed or fully nude, arranged in suggestive poses: reclining by a lake, fingers trailing along or reaching for each other’s bodies, one tickling another’s mouth with a golden reed. I neither knew nor cared that these paintings were composed by leering male artists who sought justification to paint naked women, and my favorites were those that illustrated the story of Callisto, like Francois Boucher’s Jupiter, in the Guise of Diana, and Callisto (1763).

François Boucher (French, 1703–1770). Jupiter, in the Guise of Diana, and Callisto, 1763. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 21 5/8 in. (64.8 x 54.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982 (1982.60.45)

The painting appeared at the Salon of 1765 in Paris and was one in many works by Boucher depicting scenes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Its two voluptuous figures recline upon a pile of luxurious blankets. In one hand Diana grasps Callisto’s drooping garment, which reveals her acolyte’s bare breasts, and in the other she cups her chin. In an earlier rendition of the same scene, Boucher’s figures are rearranged, but Diana’s hand remains under Callisto’s chin, tilting her face toward the goddess’s own. For a whole year of my teens, I kept a computer printout of a similar work by Federico Cervelli, Diana and Callisto (seventeenth century), taped inside a notebook. The painting features naked Callisto draped over Diana’s lap, her hand reaching behind the goddess’s head to pull her in for a kiss. One of Diana’s arms wraps around Callisto’s body while the other embraces a beautiful hound.

Thirty years later, I still marvel at the greedy satisfaction with which I studied these images, at the hunger and resilience of my adolescent eye—how undaunted it was by the lurid premise of this mythological scene.

Federico Cervelli (Italian, 1625–1700). Diana and Callisto, 17th century. Oil on canvas, 49 x 64.5 cm. Royal Łazienki Museum, Warsaw (Dep 941). Photo courtesy of Royal Łazienki Museum

The story goes something like this: Callisto joins Diana as a child, either voluntarily or as a tithe by her father King Lycaon, and takes her virginal vow. Far from a concession, this means that Callisto will never be compelled to marry a man of her father’s choosing and can live freely in the woods with the goddess and her adoring horde. Similar to the word celibacy, the word virgin in ancient Greek also translates to “unmarried girl,” implying that such a role would not have precluded sexual dalliances with other women.

While conducting researching for The Dry Season (2025), a memoir of a liberatory year spent celibate, I read about medieval young women desperate to join the nunnery, who dreamed of eventual sainthood. These girls are widely characterized as pious, sometimes maniacal in their devotion to the Lord. Why wouldn’t they be? The future prospects for medieval women were slim and grim: a girl as young as twelve years old could be offered as chattel to a man of her father’s choosing. Better to marry Jesus and live among women, serve the poor and God. And for the queer inclined? I, too, would have whipped myself with nettles and fasted for days to prove my devotion to Jesus, if there were even a narrow chance it would earn me freedom from heterosexual servitude. Who wouldn’t prefer to join the hunt and laze by the river nude, in a tangle of other women and elegant canines? Reading of these girls, I understood that Diana’s celibacy expressed a power that I, too, wanted to inhabit.

Follower of Alessandro Magnasco (Italian, 18th century). Nuns at Work, 18th century. Oil on canvas, 20 1/8 x 28 3/8 in. (51.1 x 72.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982 (1982.60.13)

In every version of the myth, Callisto comes of age in the woods with Diana and becomes the goddess’s favorite. One day, Jupiter spies Callisto napping in the forest and disguises himself as Diana. At his approach, Callisto rouses and expresses her love for this counterfeit Diana, who draws Callisto into her arms and begins to kiss her. Only then, in some versions, does Jupiter reveal his true identity, just before he rapes Callisto. In other versions, Jupiter “seduces” her—a difficult detail to parse, since the same Greek word could be used in both meanings. As a girl, I clung to the possibility that Jupiter was meant to have remained in his disguise and made love to Callisto as Diana, thereby proving the regularity of such interactions between the two.

It seems odd, now, to have so worshipped this depiction of a likely rape. I can think of no book more brimming with rape than the Metamorphoses, and Jupiter is the worst culprit. His victims are legion—among them Juno, Callisto, Eurymedusa, Leda, Hippolyta, Danae, Europa—as are the disguises he dons to approach them: a cuckoo, his daughter, an ant, a swan, a satyr, a shower of gold, a bull.

In many ways, the story of my obsession with these paintings is emblematic of many young queers’ predicament before the advent of the internet: a search for crumbs amid the grisly landscape of hetero-patriarchy, whether historical or mythological. Astounding, how great the need to ratify my internal experience with proof of its existence elsewhere, for a picture to mirror my own desires.

Even the gods suffered under patriarchy, and like many women across world history, Diana recognized the value of opting out.

Given all of this, it is easy to understand my excitement when I stumbled upon Rita Mae Brown’s 1993 novel Venus Envy on my mother’s bookshelf. Brown’s germinal lesbian bildungsroman, Rubyfruit Jungle, is widely known, but I’ve encountered few readers who are aware of this lesser-known work. The novel follows a closeted southern lesbian, Frazier, who believes she is dying and sends farewell letters in which she outs herself to everyone in her life. The melodrama of the book’s first two hundred pages entertained me, but I remember the novel for its final act.

In a literal deus ex machina, Frazier undergoes an electric shock in the art gallery she owns and awakens inside a painting of Mount Olympus. There, she encounters some of the usual suspects—Mercury and Venus, with whom she has a sumptuous threesome, and a stoic Diana. As a young, queer woman who had grown up fascinated by Greek myths and painted representations of Sapphic love, it was, well, a god shot. What I would have given for the near life-threatening ecstasy Frazier experiences via Venus, leaving “her whole body gleaming with fire.”

If I was still scouring rococo paintings and ancient rape stories for evidence of lesbian desire in the late 1980s and early '90s, then I suspect that Rita Mae Brown, who came of age in the 1950s, was similarly imprinted by the Greek and Roman mythology (along with all of Western civilization). This theory was further supported by my discovery of Brown’s membership in The Furies Collective, a lesbian feminist separatist group of the early 1970s formed in D.C. to combat “a system in which heterosexuality is rigidly enforced.”

The Furies didn’t last long, I assume for the usual reasons that radical feminist separatism fails—the fundamental rigidity of its ideology betrays members whose identities cannot be neatly categorized into a hierarchy of markers, like Black and trans women. Still, I wish I could travel back in time to gift my younger self a photo of the collective’s members, who were absolute heartthrobs. Fourteen-year-old me would have thrilled to know there was a real-life band of Sapphic huntresses who hadn’t needed a male gaze to realize their erotic desires.

The Furies Collective costume party, 2900 18th Street NW, 1971. National Park Service. Photo courtesy of DC Historic Sites

At thirty-four, after a nonstop chain of committed monogamous relationships, I’d had a catastrophic breakup. By that age, I mostly dated women and was surprised to find that my queerness hadn’t inured me to the deeply entrenched dynamics of that heterosexual system. I still instinctively privileged my partners’ desires over my own and had contorted my true nature in order to satisfy them. Like the separatists, I understood that it was difficult to liberate one’s own consciousness while actively participating in the systems that subjugated it. So I, too, chose to opt out.

The year I spent divested from sex and romance was the most transformative of my life. I did not laze by the river with my breasts out, or make out with any fellow nymphs, but otherwise I lived that old dream: to spend my life as my own—making art, contemplating love and nature, surrounded by women and dogs. I did not have to starve, whip myself with nettles, take a lifelong vow, or limit my social circle to only those who shared a single identity. I just had to bring a little of Diana’s ethos into my life.

View of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Diana (1893–94) in The Charles Engelhard Court (Gallery 700) in The American Wing. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2014

Now a happily married woman, I have miraculously managed to expand those freedoms. I credit that transformation to my celibate time and the work it made space for. I am also thankful to the divine huntress, who embodied a higher standard than the ones most girls are offered. It is in her lineage that I enjoy a life of autonomous body and spirit, safe and strong, in league with the moon and trees, always recruiting more maidens to my cause, happy to say no whenever I please.