Dear Martin,

It’s a Sunday in late spring. I’ve taken the train from Brooklyn to the Lower East Side to check out the handball court you painted more than forty years ago. The sky is gray clouds punched through by pure cerulean, and the little park, nearly empty of people, is so quiet you can hear the wind untangling from the trees.

A firmament of brick tenements rises behind the handball court, just like in your painting. The city has changed so much in the years since you last lived here that no structure can be taken for granted. But the wall is still standing, too, coated with a patchwork of paint in different industrial shades, each layer an offensive tactic in the ongoing war against graffiti. On the wall—the side facing east—someone has tagged “LE$ E-MONEYBAG$” with a Sharpie, a modest yet defiant salvo.

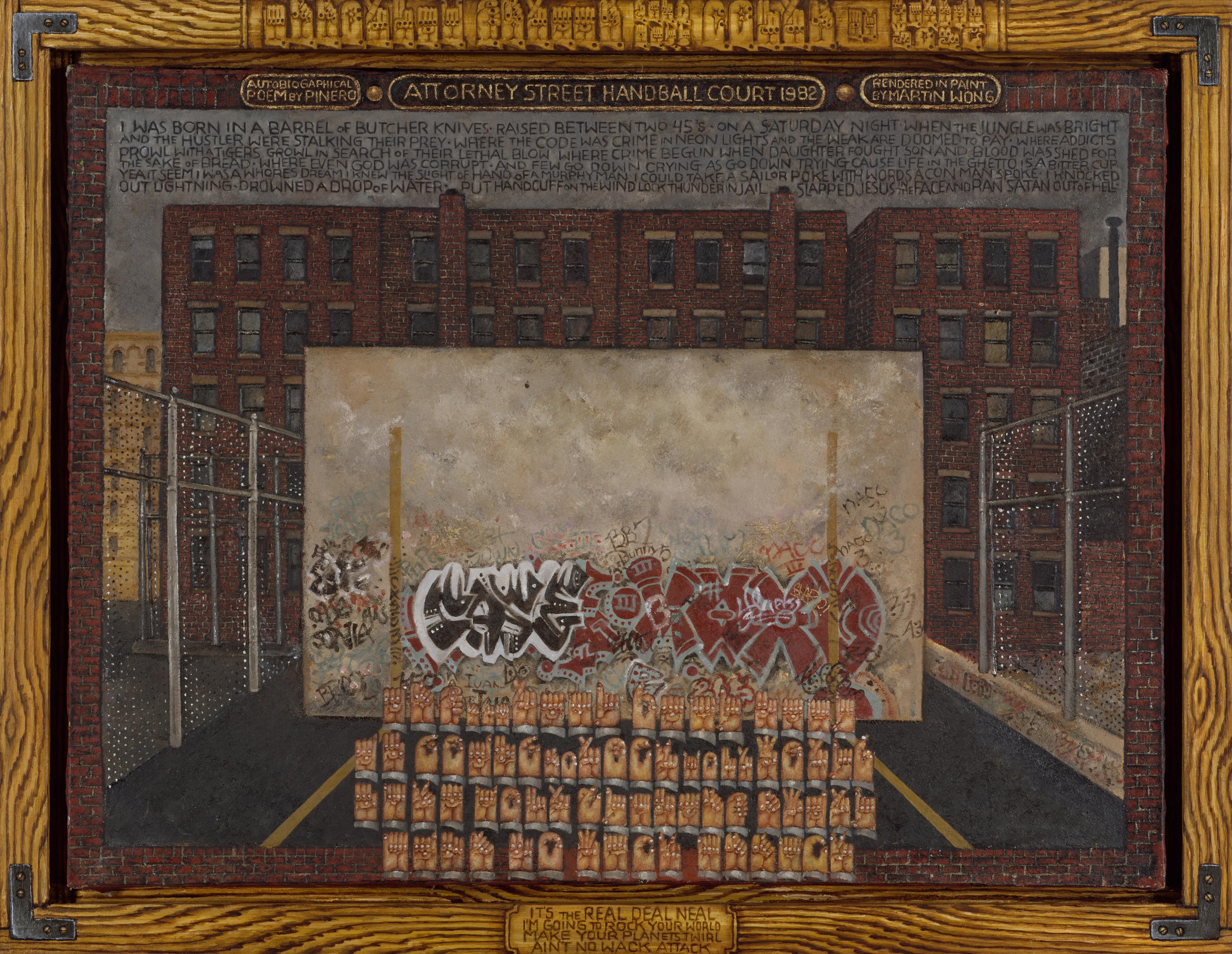

Martin Wong (American, 1946–1999) and Miguel Piñero (American, 1946–1988). Attorney Street (Handball Court with Autobiographical Poem by Piñero), 1982–84. Oil on canvas, 42 in. × 54 1/4 in. (106.7 × 137.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edith C. Blum Fund, 1984 (1984.110) © The Estate of Martin Wong

The court itself is narrower than I expected, and more green. Leafy branches have sprouted wildly through the diamond holes in the chain-link fence. Two men lie sleeping nearby, possibly passed out from a night of boozing, their heads resting tenderly on each other’s shoulders.

Apart from this painting, graffiti hardly appears in your work. To a superfan like you, reproducing another artist’s graffiti must have struck you as visual plagiarism—like redoing a Van Gogh. But the Attorney Street handball court was a special case. The playwright Miguel Piñero, your friend and, briefly, lover, asked flat out if you’d make a painting of it. Little Ivan, one of a four-man posse Piñero ran with, had painted a fresh tag on the wall. All understood that oil on stretched canvas had a better shot at immortality than spray paint on a wall. You were the man for the job.

The painting’s sunless patina of brick, steel, and concrete makes it look like it was forged at a smithy, thick with the sediment of a now-legendary time. With this one painting you entered a zone of quantum entanglement—the Nuyorican Movement of the Lower East Side, the pantheon of downtown artists like Basquiat and Haring code-switching between the streets and blue-chip galleries, and the Chinese landscape painters from centuries earlier who wrote poems in the sky.

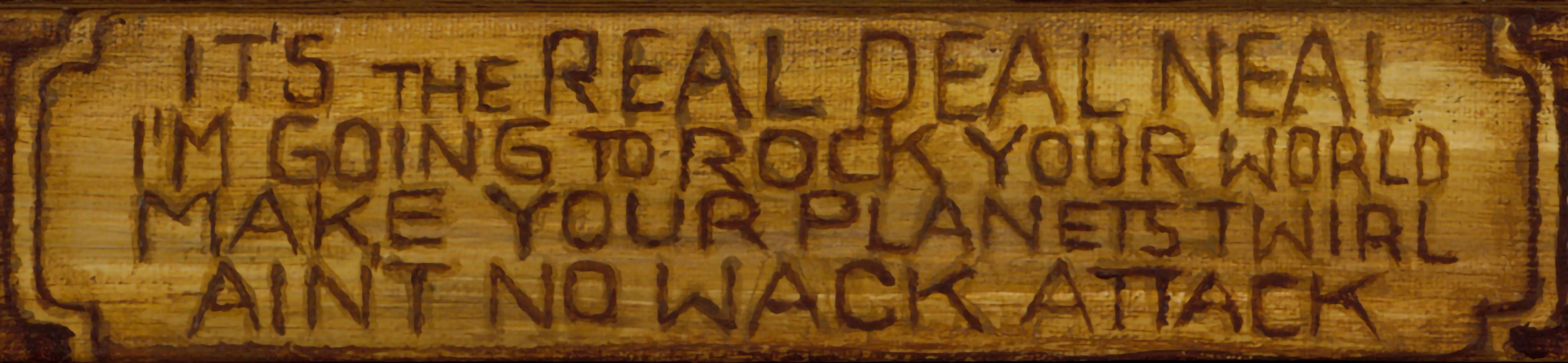

It was 1982 when you started making this work. You were working at Pearl Paint on Canal Street at the time, looking the other way while your graffiti artist pals availed themselves of five-fingered discounts. Piñero, relatively flush from a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Hollywood paycheck for playing a drug dealer in Fort Apache, The Bronx (1981) was covering part of your rent so you could devote more time to painting. (That trompe l'oeil brass plate at the bottom of the painting’s wooden frame—and reinscribed above in your signature fingerspelling—is a line from the movie.)

Brass plate on the frame of Attorney Street.

Since then, the city has softened in some ways and hardened in others. These days it’s the landlords doing the mugging. At your old apartment on Ridge Street, just a three-minute walk from the park, a one-bedroom (virtual doorman, granite kitchen, wine cooler) is going for damn near $3,800 a month. At the bodega at the foot of the building, I chat with the Dominican guy behind the register. The bodega is old-school—the kind where Wonderbread and Takis are stacked vertiginously on the same shelves as shower caps and pencils.

Business is bad, the man says darkly. I don’t say but can’t help but think it’s because his store no longer computes with the young professionals who’ve moved into the neighborhood.

I retrace my steps back to the park, intercepting a small group of friends barbecuing in a nearby cul-de-sac. Do people still use the handball court, I ask a slight man in his late forties. He grew up on the Lower East Side and now drives a delivery truck for Bimbo.

Not really, he says. The courts on First Avenue are where the action is. This one’s too out of the way.

I explain why I am there, and who you were. He brightens and shows me the tattoo of a gas-masked figure wielding an Uzi that crawls up his forearm from wrist to elbow. Look it up, he says.

Courtesy of the author

Later I do. It’s a reproduction of a famous mural that once graced Allen Street by your friend, and for a year, roomie, Lee Quiñones. In 1978, Quiñones became the first to paint a handball court wall from top to bottom—effectively catapulting graffiti from a literal underground subway art form to an above-ground phenomenon.

You were obsessed with that wall, which stood in the yard of a middle school about a ten-minute walk from here. An inveterate collector (your side hustle was buying antiques from Christie’s and flipping them at Sotheby’s), you knew gold when you saw it.

Lee, let’s go and excavate that wall! Quiñones remembered you insisting. You were convinced you could buy it from the city. And put it where? In your apartment? Quiñones laughed, marveling with affection at the grandiosity of your impossible schemes.

Lee Quiñones (Puerto Rican, b. 1960). Graffiti 1979, Whole Handball Court, Lower East Side, NYC, 1979. Mural. Photo by Martha Cooper

Little Ivan’s graffiti lives on in your painting; not only that, The Met bought it, which is like having triple life insurance. It must have pleased you to inscribe in a single work your beloved Loisaida constellated with Piñero and Little Ivan’s art. You were each other’s chosen family, although I bet the crew who sometimes crashed at your place and crowded in your kitchen for improvised dinners of bodega staples—orange soda, Ding Dongs, Cheetos, and Twinkies—would’ve poked fun at the earnestness of that term.

At what point did you realize you were painting a version of the city that was disappearing?

(As for you—not Martin, but the you who is reading these words right now on your screen—I implore you to see this painting in person if you can, unmediated by digital pixels. Only then will you truly absorb its fulsomeness and the devotion that went into making each brick and chain link unique, as though to hold the fidelity of time itself in place.)

I’m back at the handball court where one of the sleepers has woken up. He pushes himself upright on his feet with his hands like a baby giraffe and stumbles to the wall to take a piss. He shakes a cigarette loose from a crumpled pack in his jeans: the first deep drag, and the cough it triggers, mark the start of a new day.

The handball court in 2025. Courtesy of the author

The bodega owner says he doesn’t know how much longer he can keep going: his electricity bill alone is a thousand bucks a month.

The truck driver says he plans to move to Pennsylvania. He doesn’t want to live on top of other people anymore, and the other day in Bushwick, a stranger threatened him with a gun.

That first wall of Quiñones’s was painted over ages ago. The wall itself came down in late 2024. At what point did you realize you were painting a version of the city that was disappearing? Or maybe that’s what painting always is, even when what’s captured is pure invention.

I cut across the street to the bare storefront I’d passed earlier where, through the glass, I could see a man and woman in their twenties assembling a shelf. The walls are white, as are the young people inside. I intercept the floppy-haired man on his way out the door.

What are you opening, I ask, even though I already knew the answer.

He straightens slightly, flashing a shy smile. An art gallery, he says.

May–June 2025