Art for Resilience: Sumerian Standing Female Worshipper and More

Today we bring you a selection of artworks that inspire resilience. This includes works of art that transcend postcolonial borders in Africa and North America, as well as portraits of people who rose up to face oppression. Kim Benzel, a curator in The Met’s Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, opens with a reflection on an ancient Sumerian statue.

Standing female worshiper. Sumerian, Early Dynastic IIIa (ca. 2600–2500 B.C.). Limestone, inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli, H. 9 15/16 x W. 3 3/8 x D. 2 1/16 in. (25.2 x 8.5 x 5.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1962 (62.70.2)

This worn, fragile-looking statue of a Sumerian woman from 2600 B.C. has always moved me. Excavated at the site of Nippur, in Iraq, the statue was one among many sculptures discovered in a temple dedicated to Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love, abundance, and war. The statues all represented mortal beings—most likely the elite citizens of Nippur—who commissioned images of themselves to stand in perpetual prayer before the deity.

The temple remained in use for an astounding three thousand years, until sometime in the Parthian period (247 B.C.–A.D. 224) undergoing continual restoration and renewal. With each new iteration, the statuary from the previous temple would often be buried in the walls or cultic furniture of the new temple, indicating that once consecrated, these images remained sacred even when no longer performing their original function.

This figure’s longevity and persistence—the sheer fact of her survival—speak to me every time I come face to face with her. I am utterly awe-struck that she was preserved for the three thousand years of the temple’s existence and then lasted for another two thousand years in the abandoned mound of the site, until archaeologists unearthed her in the 1950 and ’60s. Today, this worn statue of a Sumerian woman is anything but fragile; her strength and resilience speak to me and to all of our visitors at The Met.

— Kim Benzel

Met Stories

This recent episode of Met Stories features three powerful stories on the theme of resilience: Tomás Vega, a paralegal, describes his lifelong dream to work at The Met and how he finally had the chance to make that a reality when he received DACA status. Sue Jeiven, a tattoo artist, explains how vitally important The Met became to her when she was faced with a diagnosis of terminal breast cancer. And Ahmed Badr, founder of Narratio and author of While the Earth Sleeps We Travel, tells how his experience as a resettled Iraqi refugee gives him a unique understanding of the tensions at play in the Ancient Near Eastern galleries, which helped him gain power over his own story of displacement.

“Kent Monkman Reverses Art History’s Colonial Gaze”

Painter and performance artist Kent Monkman in The Met’s Great Hall.

The two monumental paintings that comprise Kent Monkman’s exhibition mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) teem with references to iconic works of art in The Met collection. Monkman was partially influenced by Euroamerican depictions of Indigenous cultures, particularly those that portrayed Indigenous people as part of a “vanishing race.”

But as Monkman reminds us, First Nation peoples have not, in fact, vanished—and their rich cultures are very much alive. Monkman’s two paintings recast American history with Indigenous people as protagonists, and in doing so, declare a more inclusive view of American history.

In this article by the exhibition’s curator, Randall Griffey, uncover Monkman’s references and see how he challenges a colonial narrative of art—particularly one that has historically been propagated by museums like The Met. The paintings, Griffey writes, are “a testament to, and celebration of, Indigenous resiliency over time, particularly in the face of pernicious and persistent colonizing forces, both political and cultural.”

My Strength Lies by Wangechi Mutu

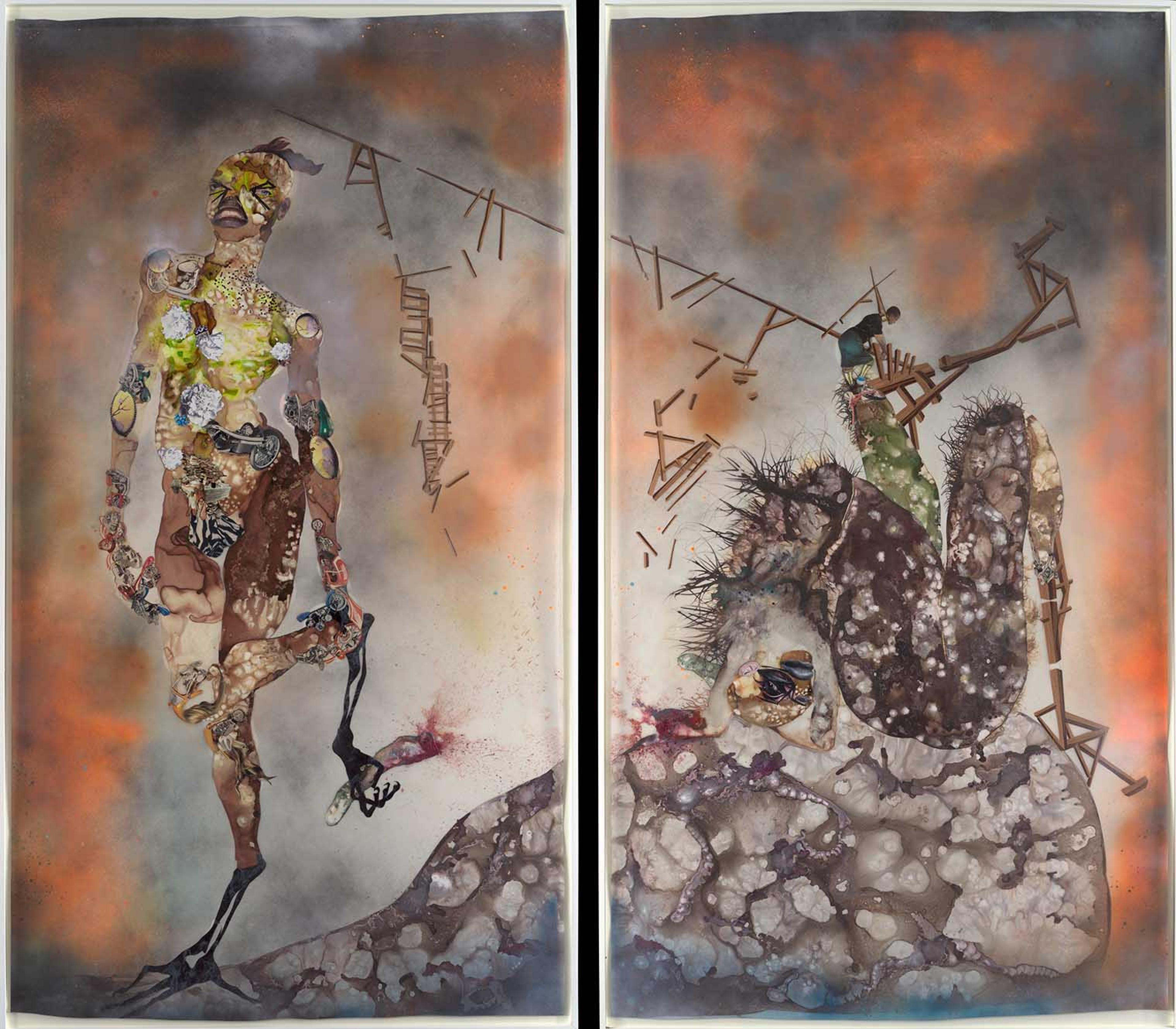

Wangechi Mutu (Kenyan-American, born Nairobi, 1972). My Strength Lies, 2006. Ink, acrylic, photomechanically printed cut and pasted paper, contact paper, metallic sequin and glitter on two mylar sheets, each: 98 x 53 in. (248.9 x 134.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Bequest of Gioconda King, by exchange, 2019 (2019.133a, b) © Wangechi Mutu. Courtesy of the Artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Wangechi Mutu made the four sculptures that occupied The Met’s facade last year, but in 2019 the Museum acquired another work by the artist: a massive diptych—each panel over eight feet high—depicting a harsh apocalyptic landscape occupied by a strange, humanoid figure.

In this essay, illustrated with dozens of gorgeous photographs, curator Kelly Baum reflects on the fantastic world that Mutu creates and the artwork’s motifs of resiliency. “We are witnessing the aftermath of a violent struggle, possibly an act of genocide, colonial incursion, or alien invasion,” Baum writes. “Mutu’s narrative and setting might be bleak, but signs of hope and optimism are nonetheless present.”

For example, the figure bears female attributes, which may suggest women’s resiliency in a world that often oppresses their bodies. Or perhaps the detail of a Black figure repairing a wooden structure alludes to building a world with greater equality.

David Driskell on Aaron Douglas’ Let My People Go

In this 2015 MetCollects video, David C. Driskell explains how Aaron Douglas, a leading painter in the Harlem Renaissance, came to Manhattan in the 1920s to “blossom” and be “revitalized.” He traces Douglas’s empowering imagery to his study of the history of Egypt, Songhai, Mali, and other empires of Africa.

The video, which features archival footage of Douglas in his studio in 1937, focuses on the symbolism of collective struggle in the painting Let My People Go (ca. 1934–39), which was acquired by The Met in 2015. Driskell, a leading scholar of African American art, an artist, and professor emeritus at the University of Maryland, College Park, sadly passed away in April due to the coronavirus.

To explore the painting further and read an essay by the curator, explore the MetCollects photo essay.

Baaba Maal profile

Senegalese singer Baaba Maal performed an acoustic concert with Cheikh Ndiaye (left) at The Met on March 9, 2020. Photo by Paula Lobo

The Sahel is a vast region of Africa, just south of the Sahara Desert, that spans from the western coast across the continent. Historically, the Sahel was a relatively unified region, home to several of the world’s most powerful and influential empires.

Famed musician Baaba Maal hails from Senegal, one of about a dozen countries whose borders were formed when European colonizers retreated from the Sahel in the mid-twentieth century. Maal makes music that transcends the postcolonial identities of modern-day Senegal, Mauritania, Niger, and Guinea, and instead reclaims the transnational identity of the Sahel.

In this profile of the musician, hear excerpts from Maal’s recent acoustic concert at The Met and tour the Museum’s exhibition Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara. Maal’s perspective on the exhibition illuminates the resilient spirit of the Sahel, which lives on in his music. As Columbia University professor Mamadou Diouf says, Maal “carries the stories of our identity.”

Kim Benzel

Kim Benzel is Curator in Charge of the Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art.

See a list of articles published by the editorial team in the Digital Department at The Met.