Paintings Uncovered setup for the fall 2014 MediaLab Expo. Image courtesy of the author

From Don Undeen, Senior Manager of MediaLab:

The MediaLab at the Met is a place for creative technologists to have close encounters with the Met's collection as well as the experts that study and care for it. Over the course of a semester, graduate students from New York City's design, technology, museum, and media studies programs meet with and present to Museum staff on a regular basis to develop their ideas into functional demonstrations that help us think about ways that new technology can impact visitors' experience of the Museum. We don't expect every project presented at the MediaLab Expo to end up in our galleries, but it is fun to imagine what kind of museum it would be if you could point a flashlight at a painting and see the layers underneath!

«Paintings Uncovered is an interactive interface that allows users to explore the hidden layers found beneath a painting's surface. Painters frequently paint over paintings for various reasons—even sometimes with a completely different subject. One reason for this may be that the original painting didn't sell, so the artist reused the canvas to create an entirely new painting. Examining the underlying surfaces of paintings through powerful technology provides valuable information about the artworks.»

Pablo Picasso is known to have often painted over his paintings. Here, one can see Woman Ironing (1904) (left) and the portrait of a man found underneath (right). Read more in the New York Times. Image courtesy of New York Times

Underlying scenes in paintings can reveal the artist's process of creating the work. Reflectography—an infrared technique to detect layers beneath the top surface of a painting—revealed that Leonardo Da Vinci painted three versions of Lady with an Ermine (one without the ermine and two different versions of the animal).

The three versions of Lady with an Ermine by Da Vinci. Read more in BBC News. Image courtesy of BBC News

These underlying images reveal fascinating stories about intent and process that are not evident when viewing the painting, so I wondered: "How can an interactive interface successfully teach people about hidden images in art?"

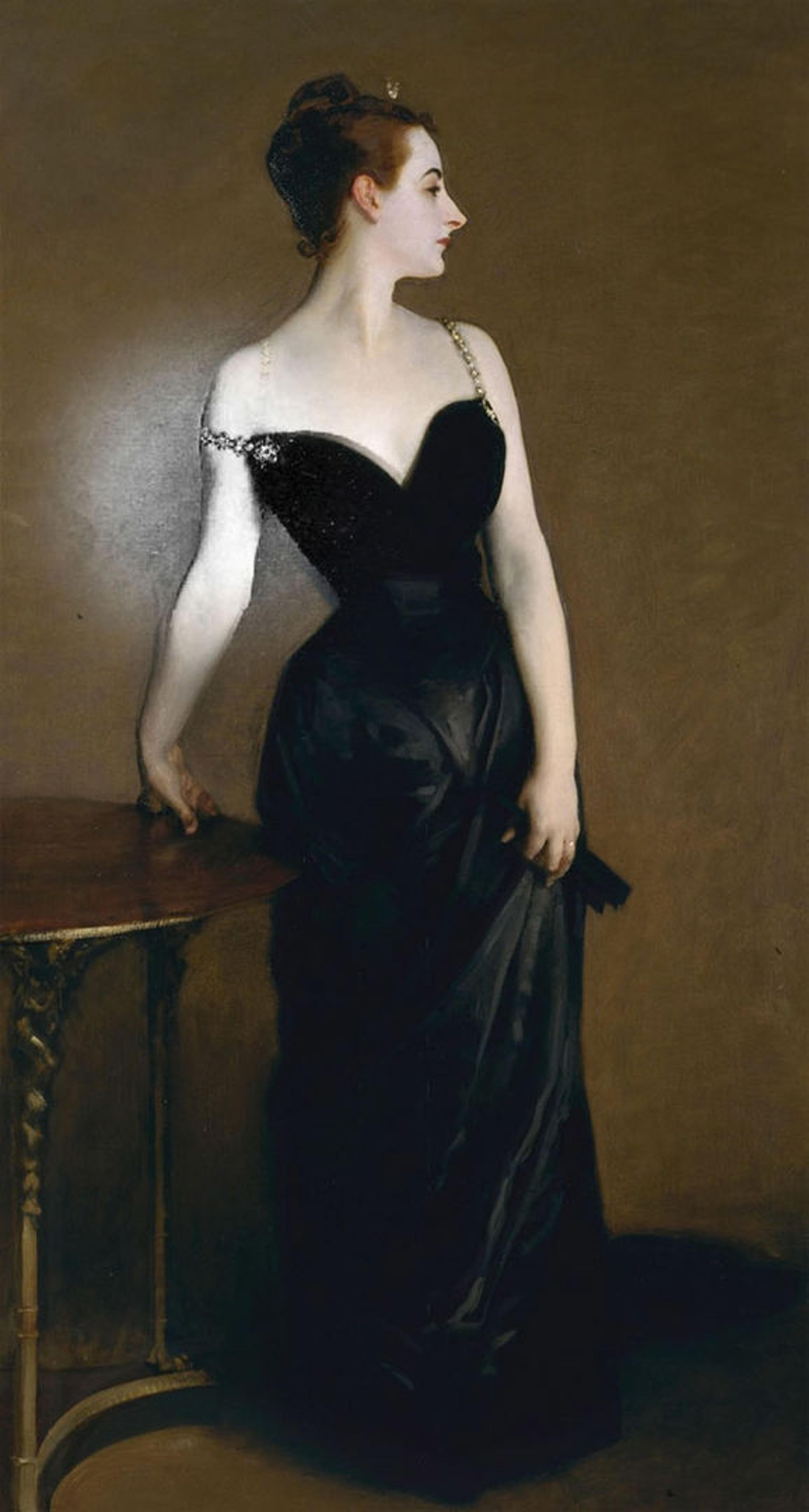

To explore this question, I chose to work with John Singer Sargent's portrait of Madame X. The portrait features Madame Pierre Gautreau posing in a black dress, her pale skin strikingly contrasted against the dark garment and background.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), 1883–84. Oil on canvas; 82 1/8 x 43 1/4 in. (208.6 x 109.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916 (16.53)

This portrait was a subject of controversy when it was unveiled at the Paris Salon in 1884. In the original painting, the strap on Gautreau's right shoulder seductively rested off her shoulder. Viewers were shocked—causing a scandal that resulted in the mockery of both Sargent and Gautreau—and subsequently ridiculed the color of her skin and pose. Sargent, who had painted Gautreau as she was originally dressed, painted over the strap so that it was secured on her shoulder, and, in 1916, sold the painting to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

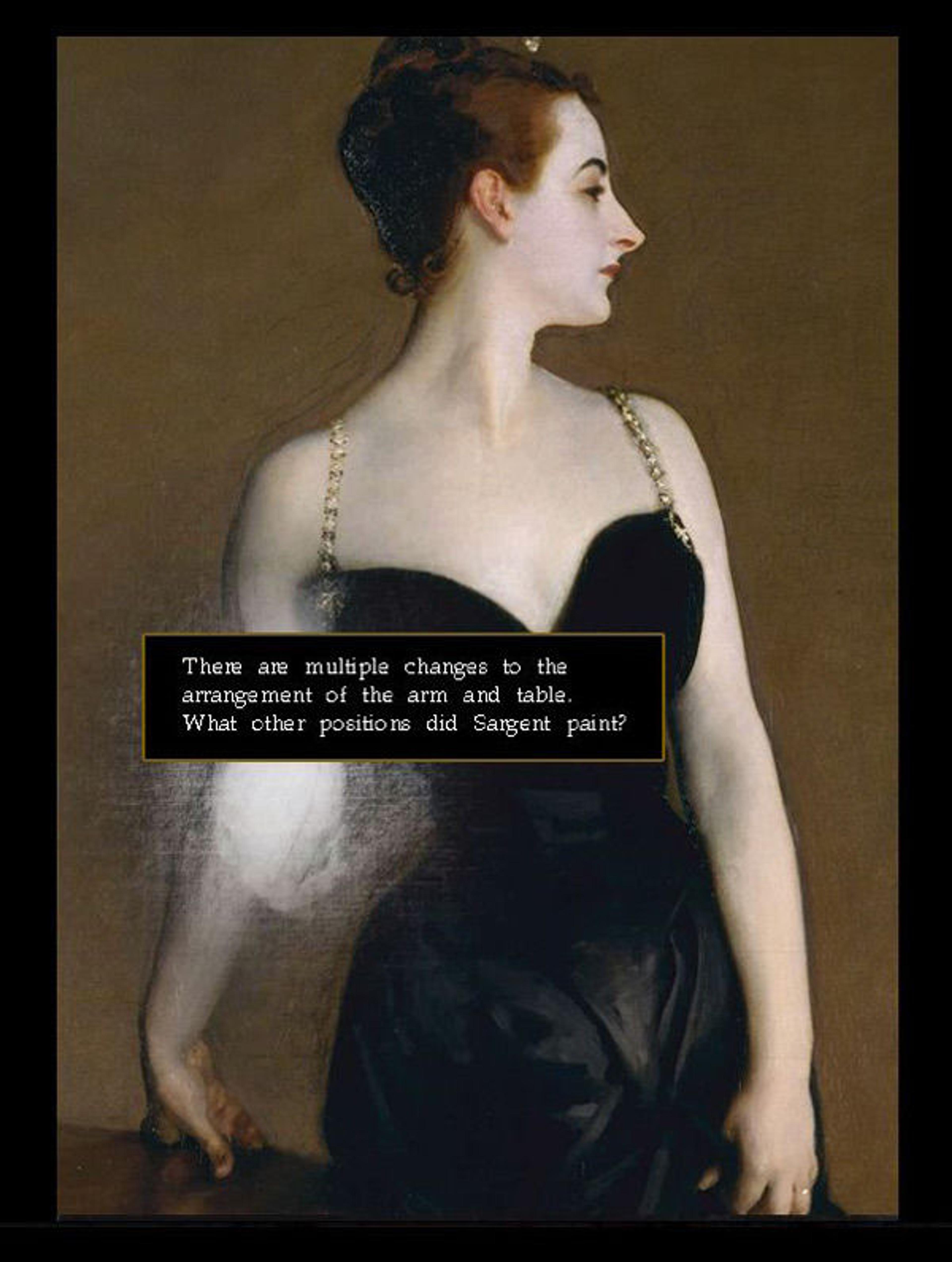

The original shoulder strap was actually off Gautreau's shoulder, as seen with Paintings Uncovered.

This is one of my favorite stories about a painting at the Met. I wanted to experiment with sharing the story in an interactive way, so I created an interface that reacted to infrared light to reveal the original painting that lies underneath.

Revealing the Painting

With Paintings Uncovered, users are able to point an infrared flashlight at a digital version of the painting (either a projection or pulled up on a computer screen), and an infrared camera tracks the position of the light to create a circular mask on the painting that "burns through" the top layer. Moving the flashlight onto certain areas then triggers specific questions about the work.

A video demonstration of how Paintings Uncovered engages users. Video courtesy of the author

I created this capability by using openFrameworks (a C++ toolkit aimed at designers) and the PS3 Eye, a small, portable camera for the PlayStation 3. I modified the PS3 Eye by removing the infrared filter and installing a visible light filter instead (view the Instructable). I then took apart a flashlight I purchased at the dollar store (the cheaper the flashlight, the easier it is to take apart) and switched its LED with an infrared LED.

The author putting together the infrared flashlight. Photograph by Yuliya Levit

This idea was inspired by my childhood dream of becoming an archaeologist; by using a flashlight, users can "role-play" as archaeologists or researchers. I wanted to experiment with physical movement rather than creating a touch-based or mouse-based application. The portrait of Madame X is nearly eight-feet tall, and in an ideal scenario, the digital version of the painting would be projected at the same size as the original. By prompting the user to move their arms in order to examine the painting, the interaction emphasizes the portrait's size.

Paintings Uncovered engages viewers with a question before allowing them to view the revealed layer. Image courtesy of the author

Finally, I wanted to engage users with critical thinking rather than giving them the answers. As a docent for the Fralin Museum of Art, I was trained to teach people how to look at and think about art by asking visitors questions instead of immediately jumping into a lecture. I continued that methodology in this project by creating an inquiry-based experience that encourages viewers to examine the painting more closely.

Conclusion

This project was originally created with the intent to enhance tours, although further improvements should include creating an interaction where visitors can find answers without a tour guide. This really made me think about how technology can be used to tell the stories behind the artworks in museums and eventually move away from traditional labels and brochures. After all, learning about the history of the artworks is what truly enhances the museum experience and makes art memorable. I'm excited to see what other ways technology can be used for museum storytelling.