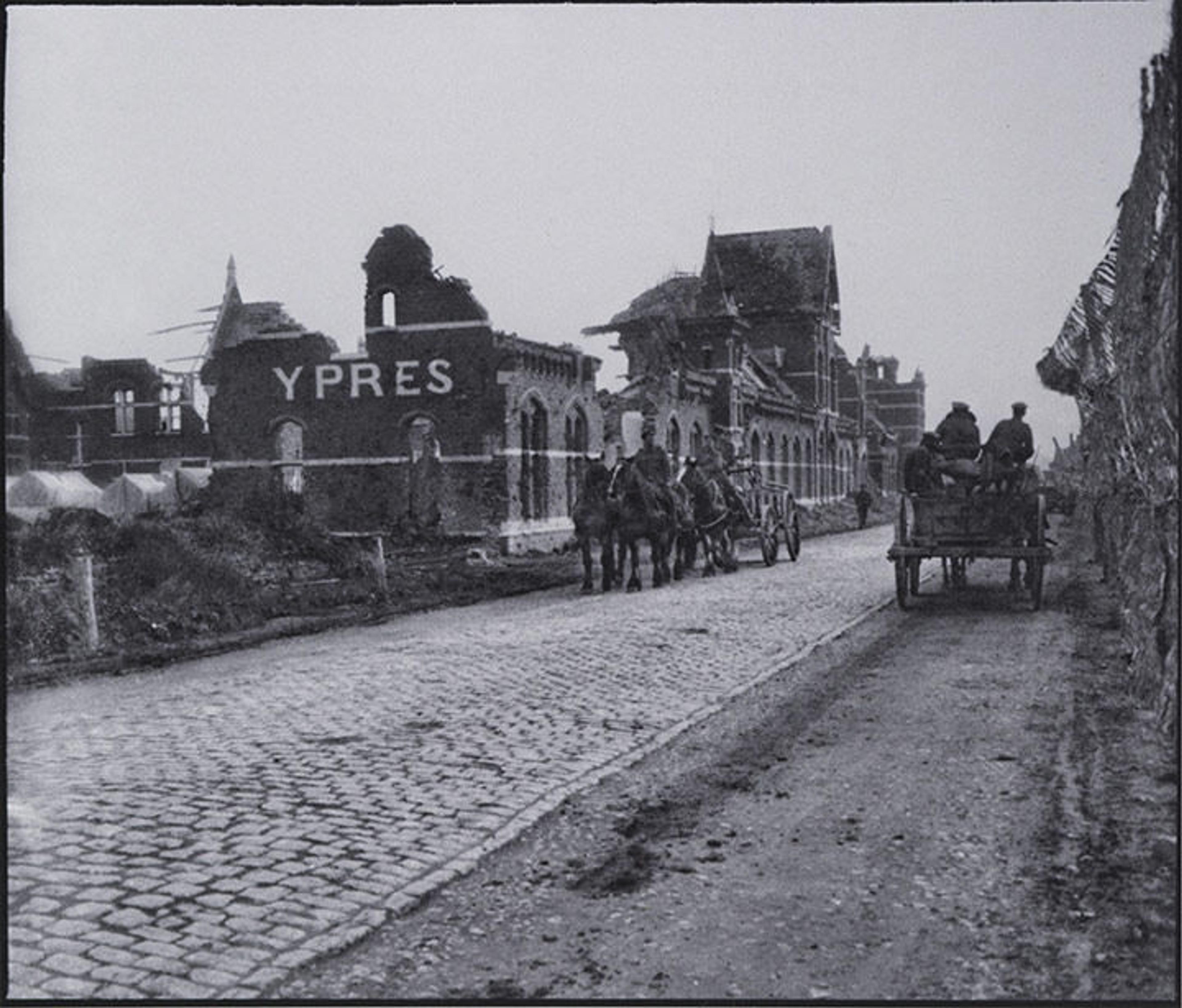

The city of Ypres, Belgium, in 1917. From The Great War Seen from the Air in Flanders Fields, 1914-1918 (Brussels: Mercatorfonds in cooperation with In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, Imperial War Museums, United Kingdom, and The Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History, 2013).

«One hundred years ago, the world was ensnared in the largest war mankind had ever witnessed—one that saw the invention of poison gas, aerial combat, the tank, machine guns, and plastic surgery, among many other things. Since 2014 and continuing through 2018, all kinds of events commemorating the centenary of the "Great War," as World War I was known at the time, are taking place all over the world, including here at The Met.»

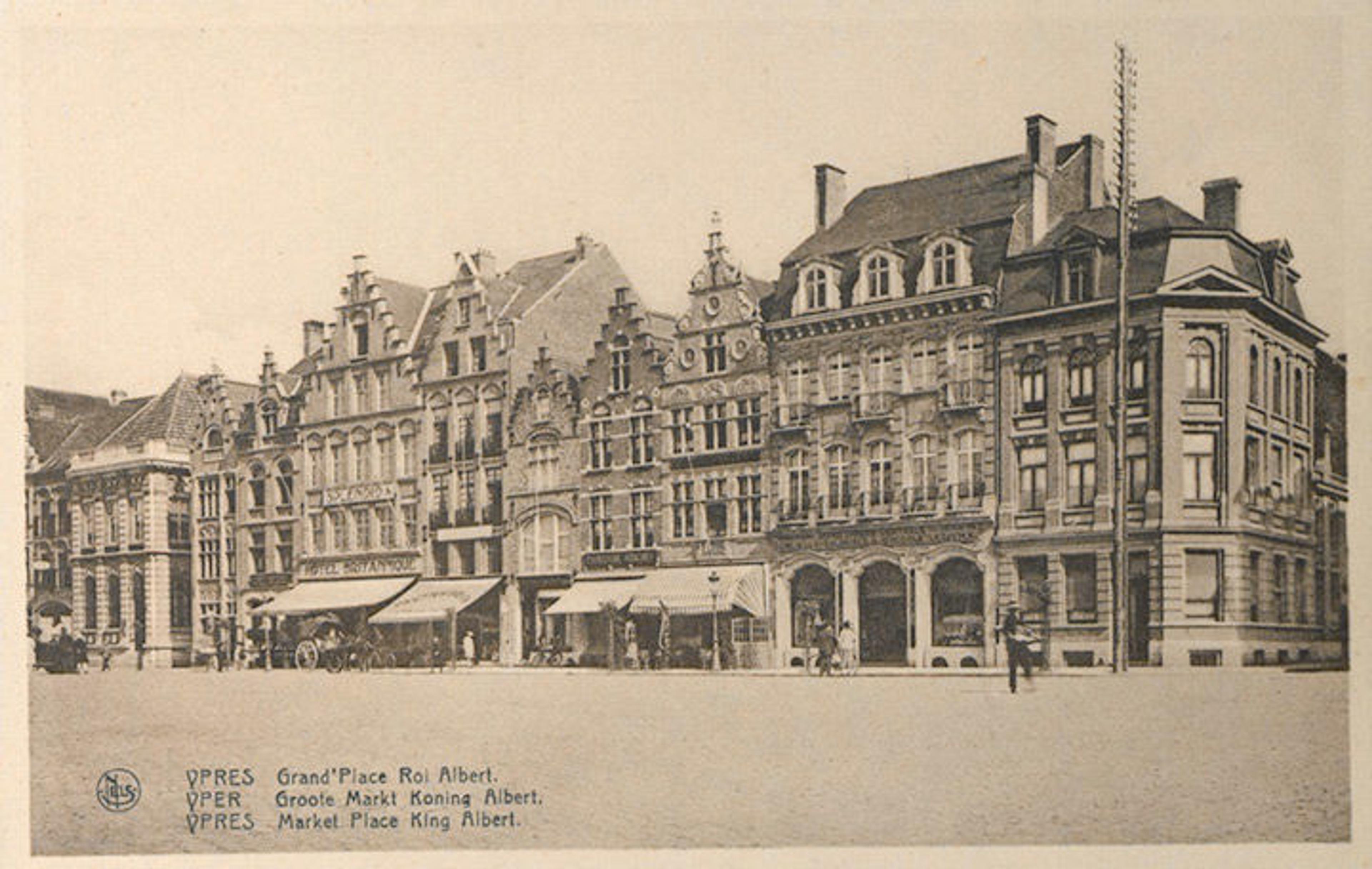

This past September, prior to presenting at a library conference in Paris, I was able to spend some personal time traveling in Belgium, including in and around Ypres (Ieper in Flemish), a charming and tranquil town in West Flanders. Ypres and the roughly 20-mile crescent of "high" ground surrounding it to the northeast, east, and south bore the sustained and incomprehensibly devastating brunt of the war in Belgium. French, British Commonwealth, Canadian, and Belgian soldiers fought for four years to keep Ypres (and therefore the Belgian port cities) from German control.

Vintage postcard of Ypres before the Great War. From the author's collection

The price for holding Ypres was hundreds of thousands of casualties (some experts—including the tour company I used during my stay—estimate that up to half a million people were killed there between October 1914 and August 1918), the complete destruction of Ypres and surrounding towns, and the utter annihilation of the landscape. I was compelled to visit Ypres to see how a place that witnessed so much death and destruction memorialized these events, while also moving past them 100 years later. It was an unforgettable experience.

Ypres in 1918—the city was completely destroyed. From The Great War Seen from the Air in Flanders Fields, 1914-1918 (Brussels: Mercatorfonds in cooperation with In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, Imperial War Museums, United Kingdom, and The Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History, 2013).

Left: Plaque at Essex Farm near Ypres commemorating the location where Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae composed his famous poem, "In Flanders Fields." Right: grave of a soldier of unknown nationality, in the Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing. Photos by the author

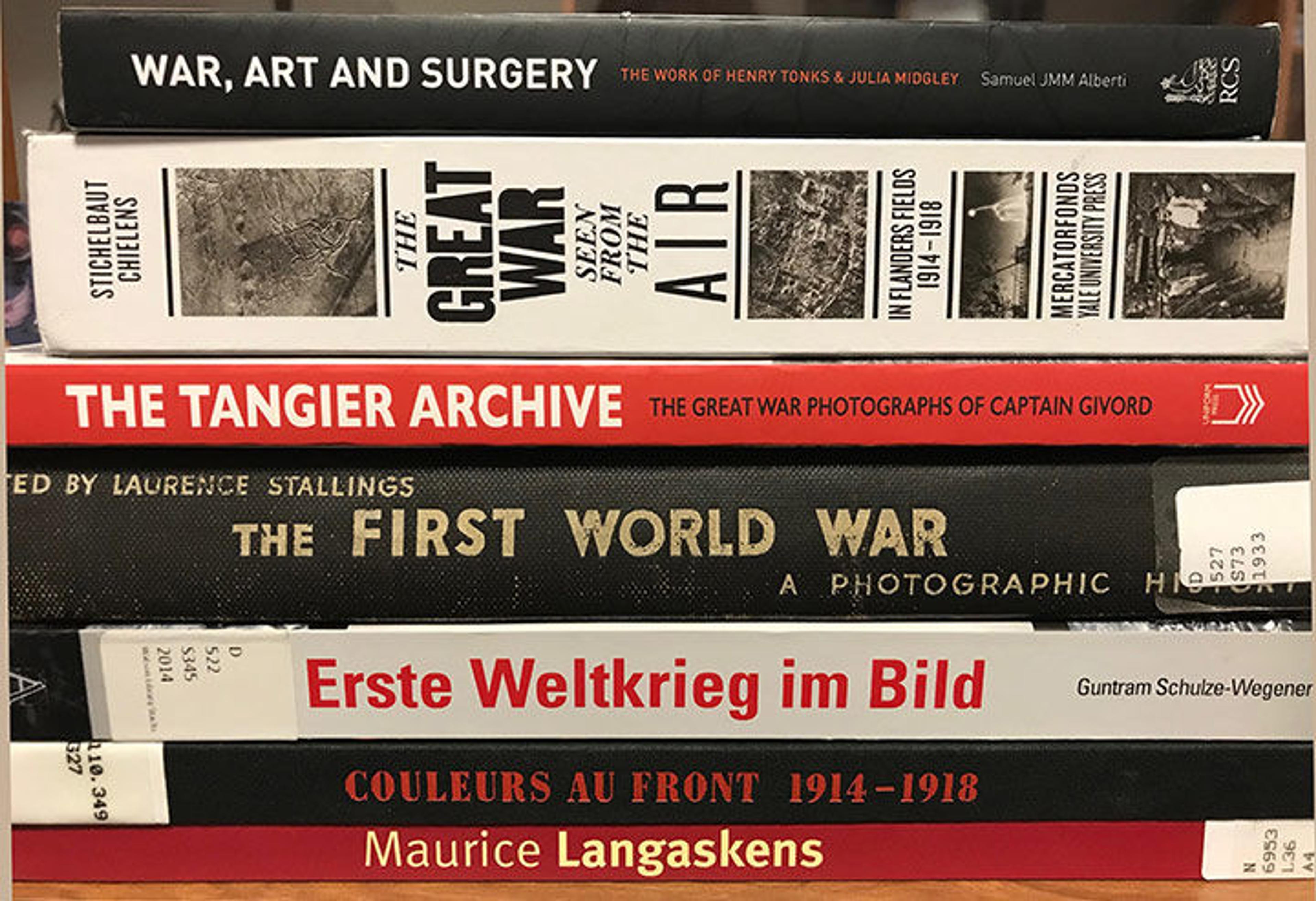

Upon returning from my trip, I was curious to see what Watson Library had on the First World War, particularly pertaining to the Belgian front and Ypres. Though it might, at first, come as a surprise that an art-research library in an art museum would have so many resources on a war that took place long ago, it begins to make sense when one considers the profound impact the war had on the art and artists of the period. This idea is explored in depth in Associate Curator Jennifer Farrell's striking and meticulously researched exhibition World War I and the Visual Arts, currently on display in The Met's Drawings and Prints galleries through January 7, 2018. The exhibition, related blog entries, and current issue of the Bulletin are must-sees for anyone interested in the Great War or the visual arts of this period.

A small selection of books on World War I in Watson Library

There are hundreds of books on the Great War in the Museum Libraries' collections, including dozens (if not more) focusing on the Belgian front. Topics range from war photography and war artists (hired to document the war in some official capacity, including for propaganda) to artists such as Otto Dix, who fought for Germany for the duration of the war. I'll highlight just a few of the books I found most fascinating, but a subject search using the term "World War, 1914–1918" in Watsonline, our library catalogue, will reveal a wealth of additional books on the topic.

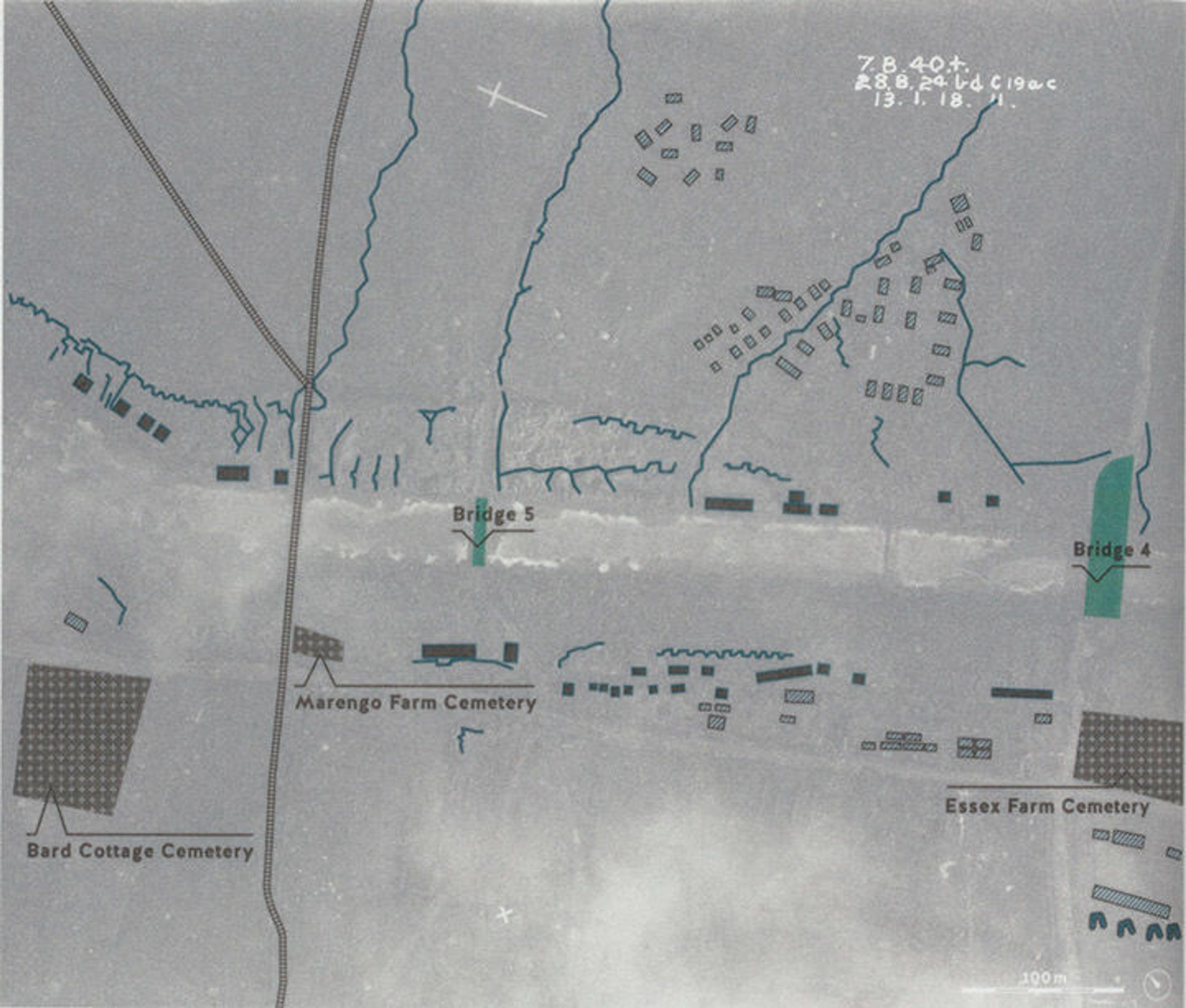

The book I simply cannot put down is The Great War Seen from the Air in Flanders Fields, 1914–1918. It merges official aerial war photography, which can be difficult for a layperson such as myself to understand, with on-the-ground contemporary photographs of the same regions and events. By doing so, it humanizes and contextualizes the aerial views, which are often sterile and abstract. In many cases it overlays the aerial photographs with color-coded paper vellum sheets that trace trenches, railroads, forests, water, buildings, and even artillery craters.

Aerial photograph of Essex Farm near Ypres, autumn 1917. From The Great War Seen from the Air in Flanders Fields, 1914-1918 (Brussels: Mercatorfonds in cooperation with In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, Imperial War Museums, United Kingdom, and The Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History, 2013).

Modern paper vellum overlay of the photograph above, indicating trenches, buildings, artillery positions, and two cemeteries, including the one at Essex Farm. From The Great War Seen from the Air in Flanders Fields, 1914–1918 (Brussels: Mercatorfonds in cooperation with In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, Imperial War Museums, United Kingdom, and The Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History, 2013).

Essex Farm Cemetery today. Photo by the author

Exhaustive research went into creating this substantive work—a joint effort of the In Flanders Field Museum, Ghent University, and the Province of West Flanders. Though I'd studied the war a bit prior to my trip, visiting some of these sites in person and spending time with this book in particular have helped me gain a much greater understanding of the extent of the devastation at the Belgian front.

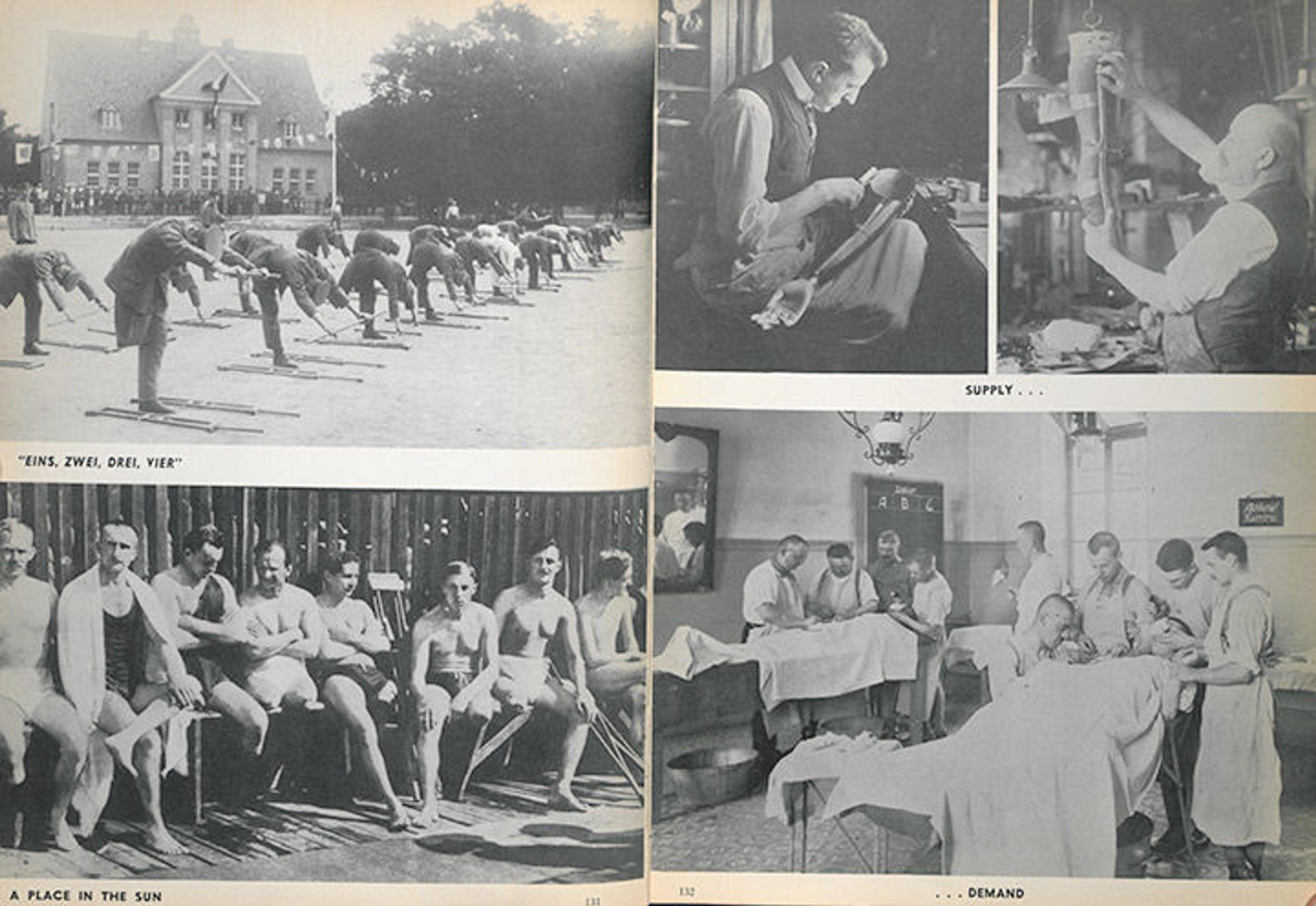

Two other fascinating war-photography books in Watson Library are The First World War: A Photographic History, published in 1933, and The Tangier Archive: the Great War Photographs of Captain Givord, published in 2015. The former is interesting not just for the mountain of photographs in it, many of which had not been published before 1933, but also for the jarringly blunt captions below the photos. The latter is captivating both for the quality of the stereoscopic photographs, which were taken by French army captain Pierre Antoine Henri Givord between 1916 and 1918, and because these photographs were only recently rediscovered, restored, and published.

The "further factual data" in the back of the book states that the photographs above depict "crippled German veterans in an exhibition drill; veterans without arms and legs at a swimming-meet in Berlin; making artificial limbs in a German factory; and operating-room in a German field hospital." From The First World War: A Photographic History, Edited with Captions and an Introduction by Laurence Stallings (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1933).

"Entrance to the town of Ypres, heroically defended by the British during four years of conflict, being an important salient in Belgium not occupied by the Germans. The net on the right hid movements on the road." From The Tangier Archive: the Great War Photographs of Captain Givord (London: Uniform Press, 2015).

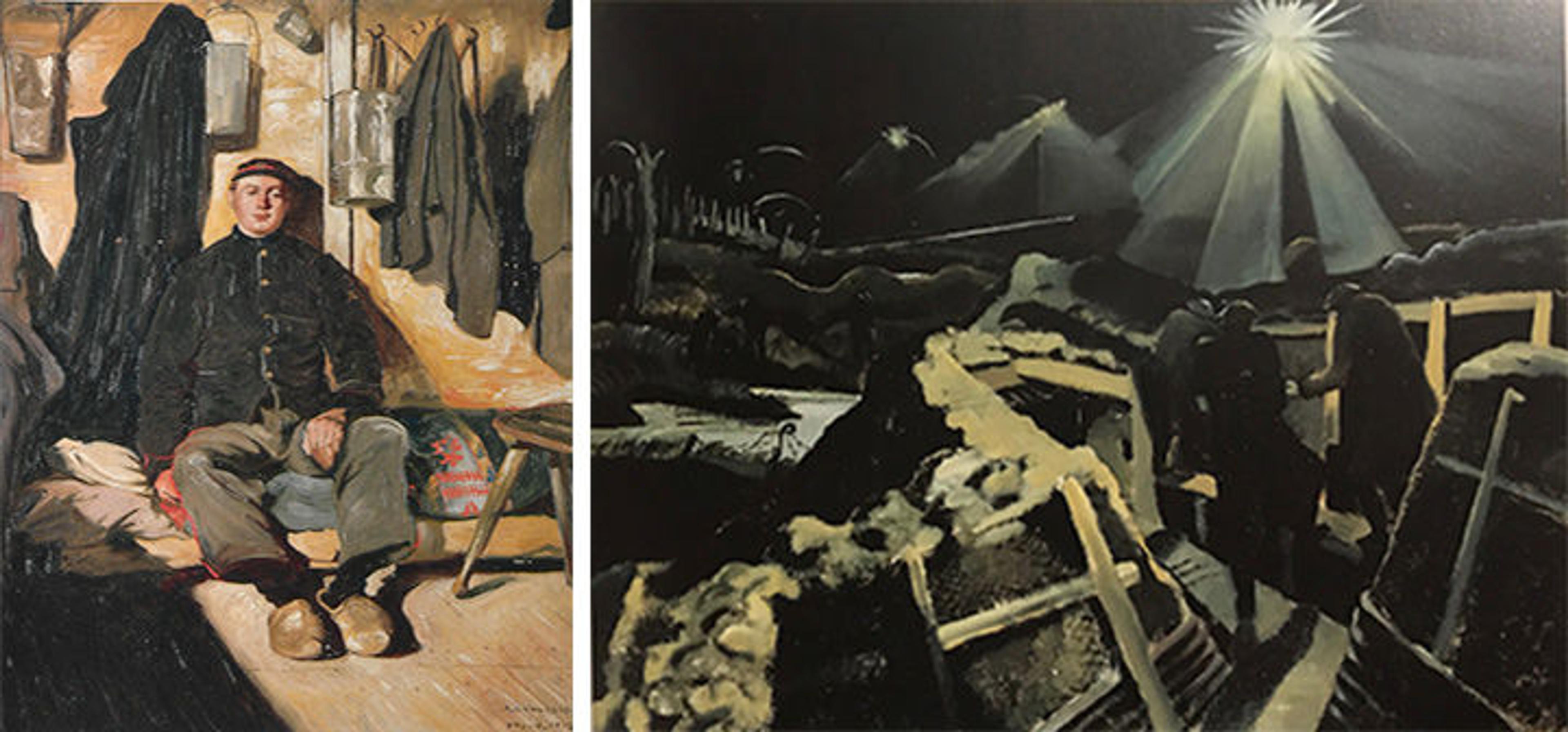

The library also owns several books on artists who witnessed the war first-hand. One lesser-known artist is Maurice Langaskens, a Belgian who fought briefly during the war but almost immediately became a prisoner of the Germans and passed his time painting expressive portraits of soldiers on their downtime. Couleurs au Front, 1914–1918: Les Peintres au Front Belge is a catalogue of a 1999 exhibition in Brussels and features works depicting the Belgian front. One of the most haunting paintings in the book, for me, is Paul Nash's The Ypres Salient at Night, painted in 1918.

Left: Maurice Lengaskens (Belgian, 1884–1946). Belgian Prisoner of War in Barracks, October 1915. Oil on panel, 26 3/10 x 19 6/10 in. (67 x 50 cm). Flanders Fields Museum. Image courtesy Maurice Langaskens, 1884–1946 (Ghent: Snoeck, 2003). Right: Paul Nash (British, 1889–1946). The Ypres Salient at Night, 1918. Oil on panel, 28 1/10 x 36 1/4 in. (71.4 x 92 cm). Imperial War Museums (Art.IWM ART 1145). Image courtesy Couleurs au Front, 1914–1918: Les Peintres au Front Belge (Brussels: Crédit Communal, 1999).

The In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres regularly hosts artists in residence, and Watson Library owns several of the resulting catalogues. The photograph below is by German artist Thorsten Brinkmann and depicts one of the large artillery craters still in existence around Ypres. The photograph has no caption, but my guess is that this is at or near Hill 60, an area that, due to its elevation (all of 60 meters), was heavily contested throughout the war. Below it is a photograph of the same or a similar crater taken during the war, while the photo at bottom-right is the crater at Hill 60 as I saw it—still massive, but, thankfully, the surrounding landscape has completely transformed.

Thorsten Brinkmann (German, born 1971). Title unknown. Image courtesy Thorsten Brinkmann: Warfare Canaries (Hamburg: Textem, 2014).

Left: "…Some corner of a field that is forever England," from The First World War: A Photographic History, Edited with Captions and an Introduction by Laurence Stallings (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1933). Right: The crater at Hill 60 today. Photo by the author

Though there was some talk during the war about turning the ruins of Ypres into a permanent memorial, reconstruction to the town's pre-war state began in 1920. Resurgam: La Reconstruction en Belgique après 1914 documents the reconstruction efforts in Belgium. The photo below dates from the 1920s, and depicts vendors in the ruins of the town's famous Cloth Hall (the reconstruction of which was not completed until 1967), backed by rebuilt structures in the Market Square.

Vendors in the ruins of the Ypres Cloth Hall, sometime in the 1920s. From Resurgam: La Reconstruction en Belgique après 1914: Passage 44, Bruxelles, 27 mars-30 juin 1985, Crédit Communal (Brussels: Crédit communal, 1985).

Looking at the beautiful architecture of Ypres now, one might get the impression that it hasn't changed in centuries. However, moving reminders of the Great War are everywhere. I'm grateful to have had the opportunity to visit, and have been amazed (though I shouldn't be, by now!) to discover so many wonderful books right here in Watson Library that have allowed me to further explore this fascinating place and time.

Ypres today. Market Square, Cloth Hall, and Saint-Martin's Cathedral. Photo by the author