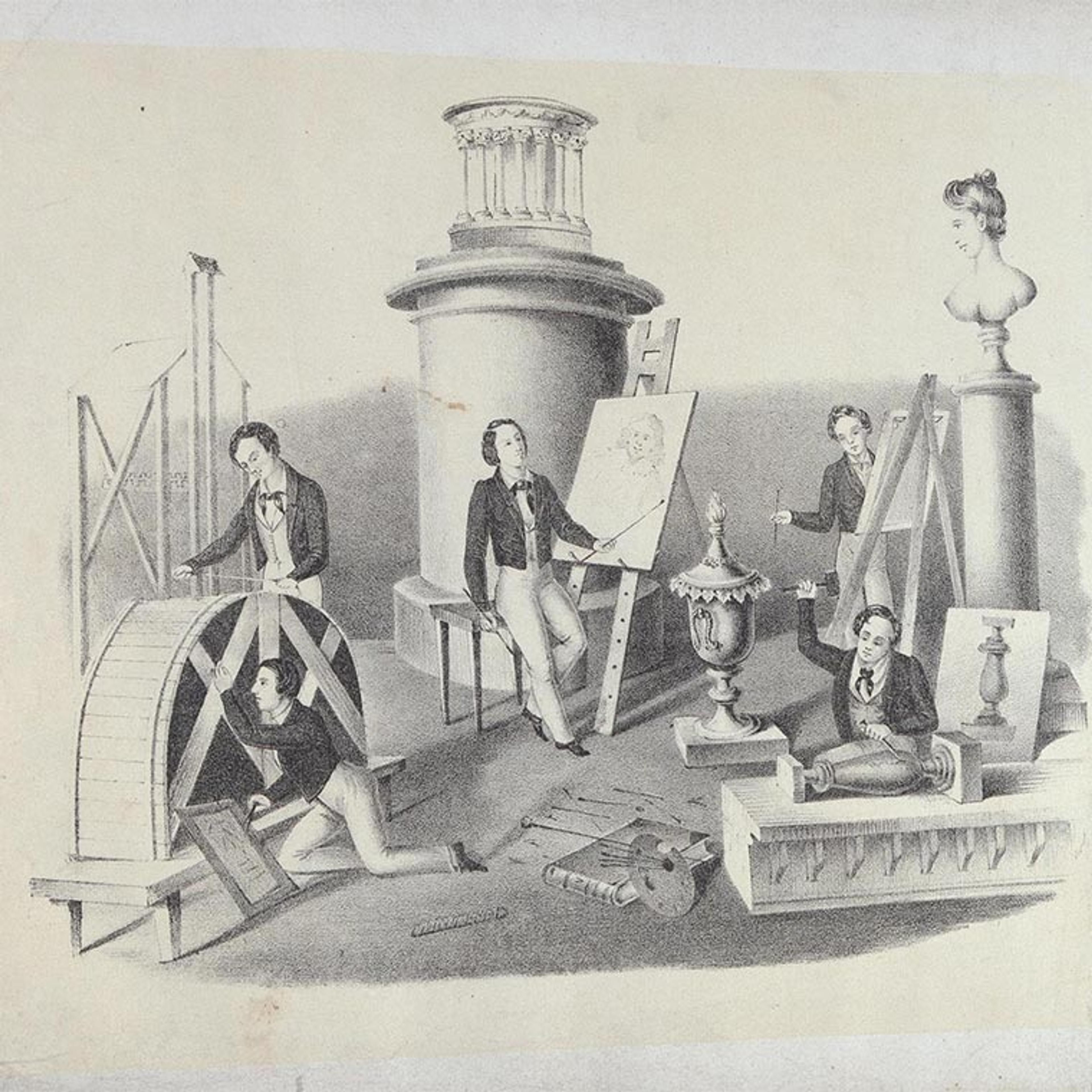

Frontispiece to Nathaniel Whittock's The Oxford Drawing Book Containing Progressive Information in Sketching, Drawing, and Coloring Landscape Scenery, Animals, and the Human Form (New York: Robert B. Collins, 1852)

"Anyone, who can learn to write, can learn to draw."

—F. N. Otis, Easy Lessons in Landscape (1853)

Each year, the Department of Drawings and Prints collaborates with Watson Library's Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation to conserve and rehouse a selection of illustrated books from The Met collection. The conservation work is funded by a grant awarded to the Department of Drawings and Prints by a New York State Library discretionary fund. Associate Curator Femke Speelberg is in charge of identifying which books should be given priority for treatment, based on their condition and the frequency with which they are consulted. Mindell Dubansky, Museum Librarian for Preservation, and I then survey the books to determine how many we are able to conserve within the scope of the grant.

This year, the selection of books consisted of 152 publications, dating from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, which focus on the study of drawing and perspective. These books were made for art students and enthusiasts, and during the eight months that I worked on the documentation, conservation, and rehousing of the volumes, they reminded me of my own days in art school at Pratt Institute, in New York, studying printmaking and book arts.

Drawing Books and Their Owners

While the books date from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, I was struck by the fact that most book titles appeared timeless and approachable for the beginner or student eager to learn:

These books were meant to be used—they supply practical information and inspiration to their readers, and many, like Easy Lessons in Landscape, with Instructions, for the Lead Pencil and Crayon, were published in multiple editions, sometimes unchanged but often altered or expanded.

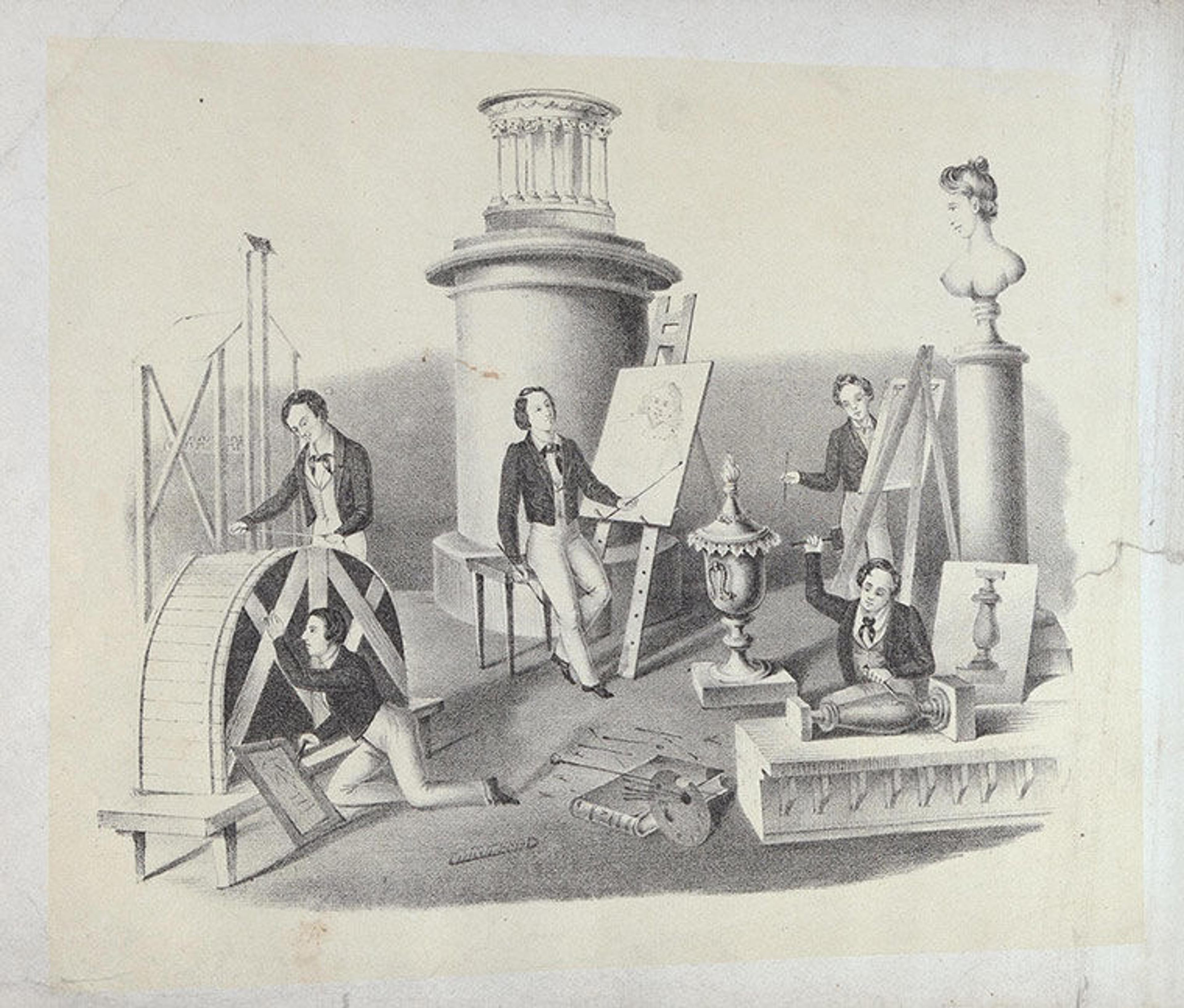

George Childs, Childs' Drawing Book of Objects (Philadelphia: John W. Moore, 1845). Left: cover before treatment. Right: cover after treatment.

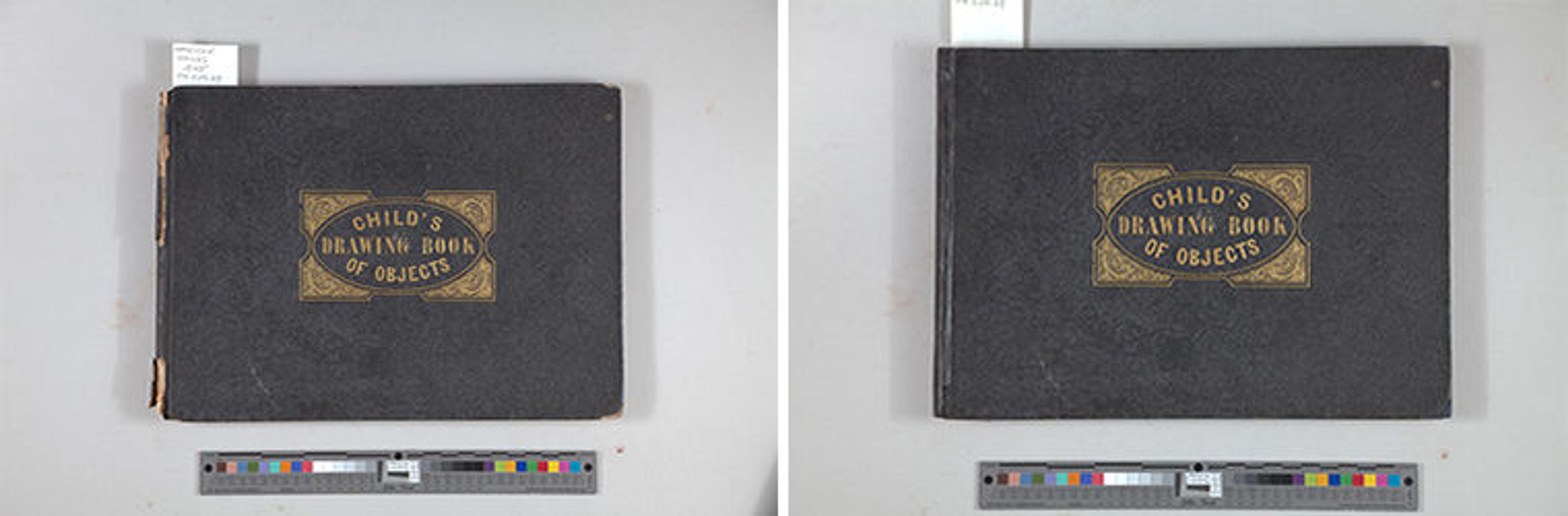

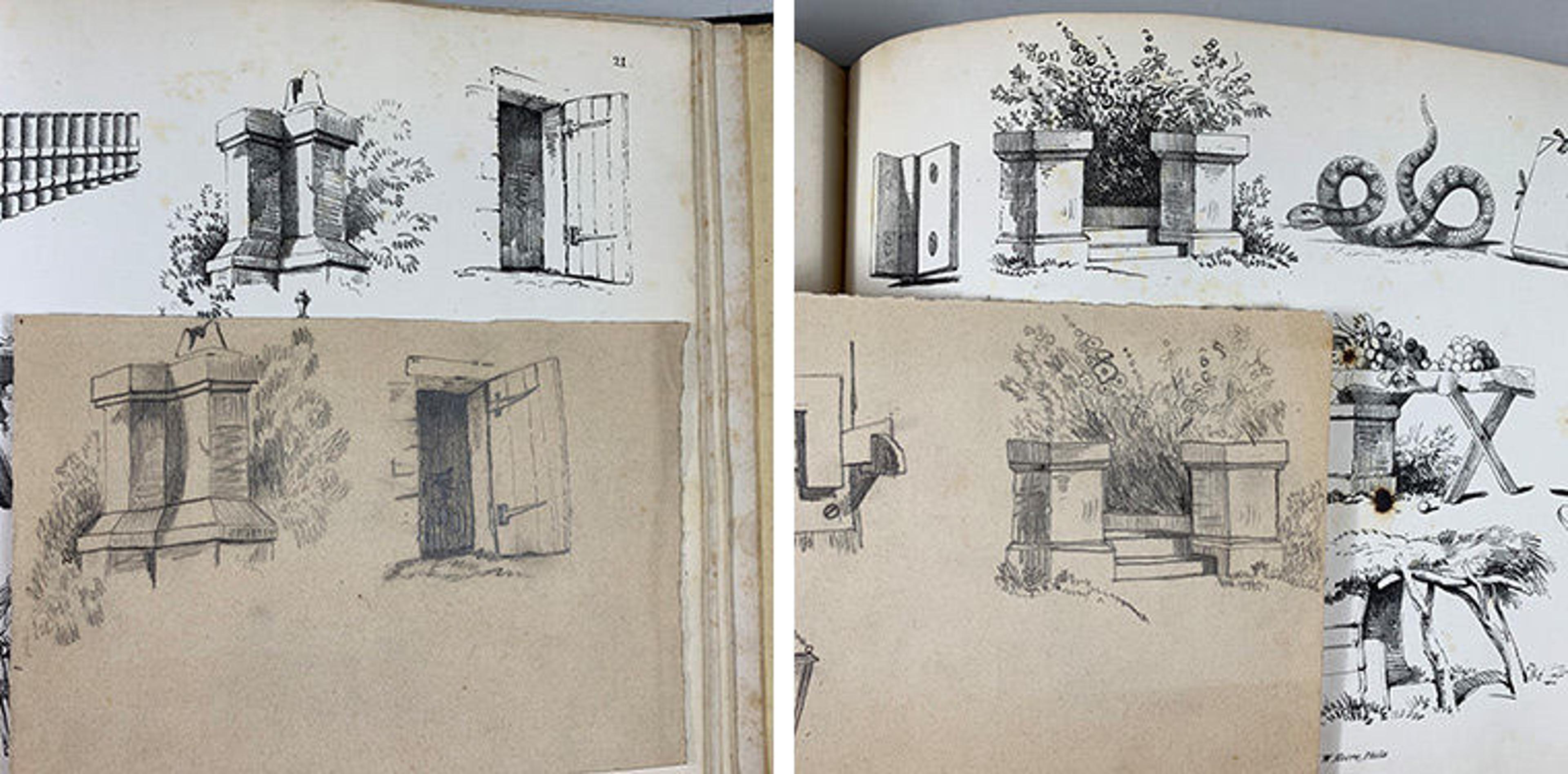

One of the books I worked on was Childs' Drawing Book of Objects. The textured bookcloth was brittle and broken at the spine. I rebacked it with matching paper embossed with the original grain of the bookcloth. Aside from the title page, the book does not contain any text, which indicates that the twenty-four bound lithographs are intended to be copied. Six original graphite sketches in the book document that a previous owner was indeed inspired to do so. Some are dated, like these two studies of an owl (below), of which one was made in July 1847, and the other four months later, in November, allowing us to see the progress the student made over this period of time.

George Childs, Childs' Drawing Book of Objects. Philadelphia: John W. Moore, 1845 (54.524.69). Left: Plate with various objects; Right: drawings in graphite drawing, dated 1847

Some books have loose scraps of paper tucked in between the pages, and marginalia with drawings inspired by the books' illustrations. I retained the original placement of loose sketches by interleaving them within the book to preserve the history of the previous owner.

Other sketches in the same book, showing architecture and plants, are not dated, but show how the student accurately copied his or her examples.

Childs' Drawing Book of Objects. Left: Plate 21 with graphite drawing, nd. Right: Plate 17 with graphite drawing, nd.

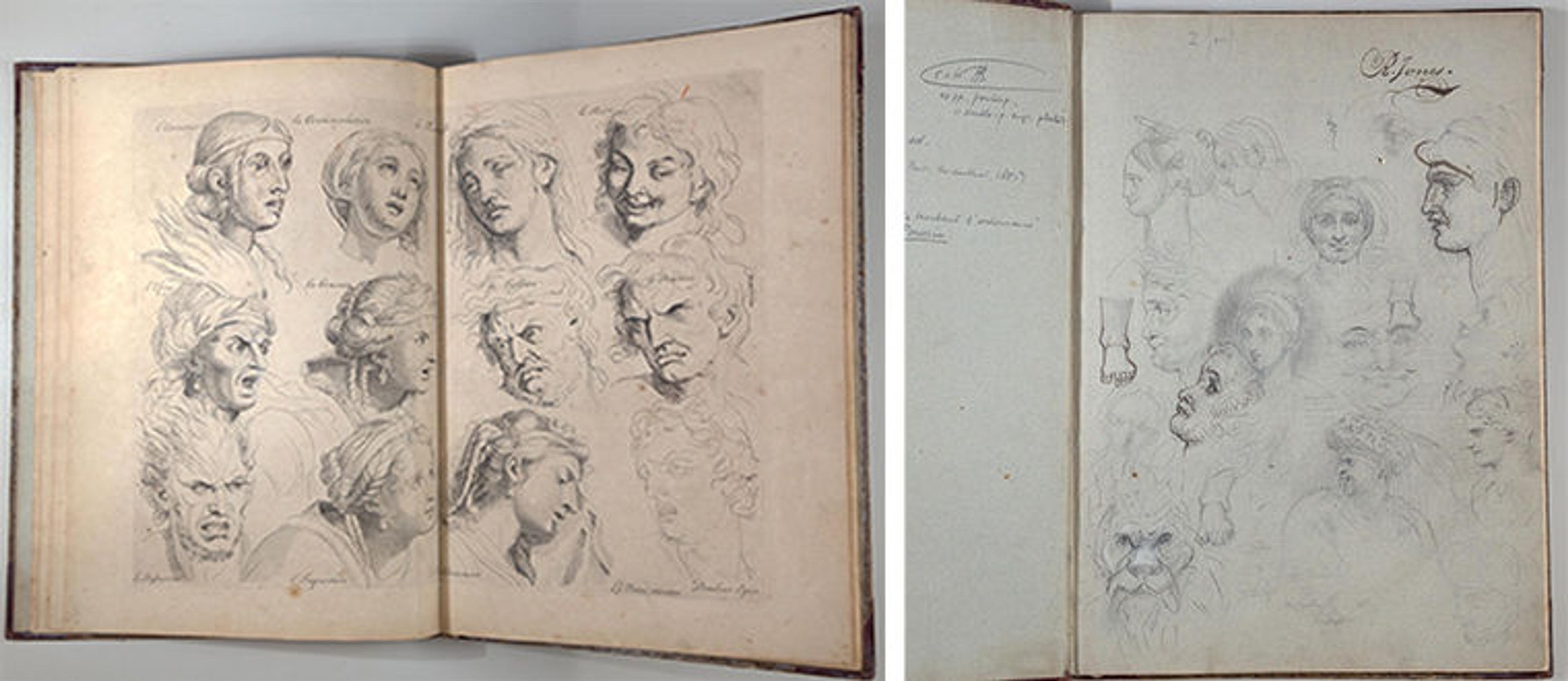

Similarly, the owner of Sentimens des Plus Habiles Peintres sur la Practique de la Peinture et Sculpture used the endpapers to practice drawing facial expressions. Interestingly, the etchings in the book inspired not only direct copies, but also sketches of other faces, perhaps drawn from life or even from the imagination.

Henry Testelin, Sentimens des Plus Habiles Peintres sur la Practique de la Peinture et Sculpture (Paris: La Veuve Mabre-Cramoisy, 1696) 68.513.6. Left: Plate 5. Right: Front endpaper.

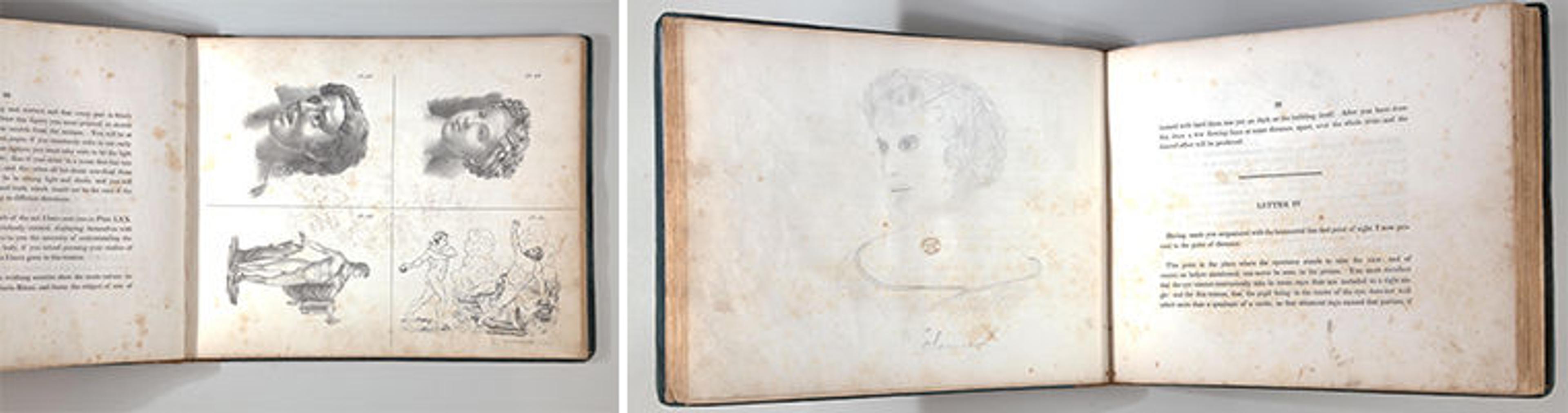

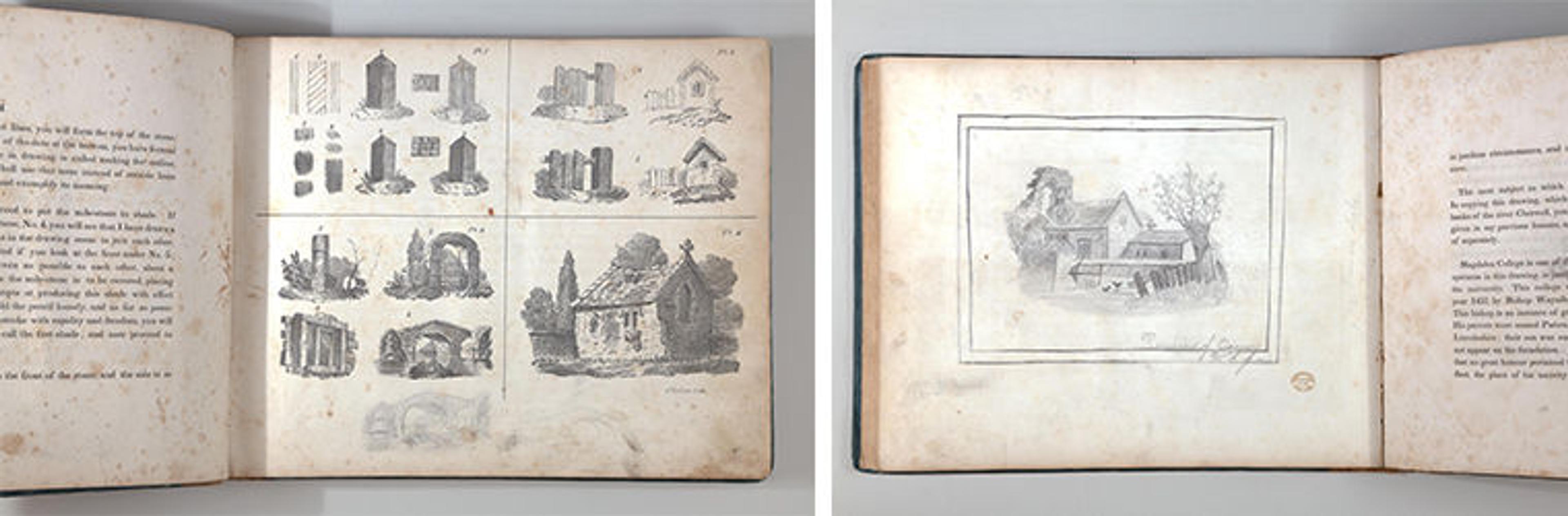

One of the Museum's editions of The Oxford Drawing Book is also filled with graphite sketches. The owner drew wherever there was a blank area, making use of the versos of plates and the margins of the pages. The number of drawings does not necessarily speak to their quality, but everyone has to start somewhere. I appreciate the draftsperson's attempt to make a portrait of "Sammie."

Nathaniel Whittock, The Oxford Drawing Book, or The Art of Drawing, and The Theory and Practice of Perspective (New York: Collins, Keese & Co., 1840). Top left: Plate 67–70. Top right: Verso of plates 13–16. Bottom left: Plates 1–4. Bottom right: Verso of plates 32–35

An Early Book on Perspective

Alongside books for general drawing education, the selection of books included a subset of more specialized literature focusing on the understanding of perspective. While some are aimed at teaching these principles, others display the incredible effects one can achieve when mastering perspectival rendering.

Perspective became one of the cornerstones and signifiers of Renaissance art. While part and parcel to the education of drawing, the more "complex" nature of perspectival drawing necessitated the development of specialized jargon and methods of illustration, and as a result perspective books became a genre in their own right. On the most basic level, the most important aspect for early modern artists to master was point perspective. While already described and practiced throughout the fifteenth century in Italy in particular, the first specialized publication on the subject was Jean Pelerin's De Artificiali Perspectiva, which was published in 1505 and is represented in the Museum by Glockendon's pirated copy of 1540. The existence of this German edition underlines the continued relevance of this publication, which was in part due to its accessibility through its highly simplified illustrations.

Aside from portraying a proper sense of depth, successful perspectival depictions were determined by an artist's ability to construct and deconstruct three-dimensional figures on the two-dimensional picture plane. As such, geometry became one of the central concerns in perspectival treatises, and various geometric shapes were illustrated, often both from a specific viewpoint in perspective, in unfolded diagrams.

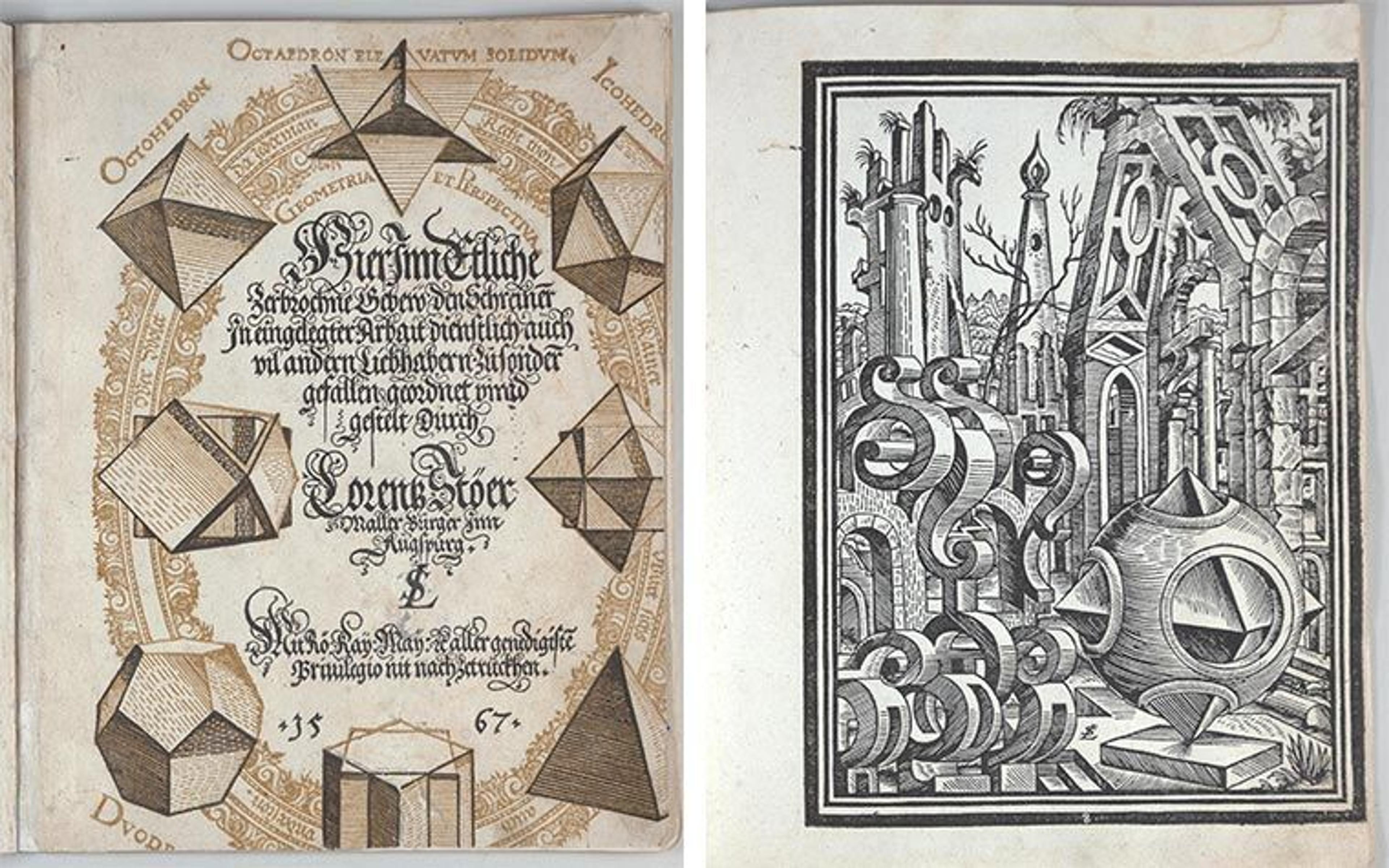

Stoer's Geometria et Perspectiva from 1567 (below) is a good example of perspective and geometry working together. The title page explains the puzzling images; they are said to be useful to artists working in the field of wood inlay, or marquetry. The art of rendering perspectival imagery in marquetry was popular in Italy throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and was adopted in southern Germany as well. Several cabinets from the late-sixteenth century with decorations in the style of Stoer's prints are known, one of which can be found in the Museum's collection.

Lorenz Stöer, Geometria et Perspectiva (Augsburg: Hans Rogel, 1567). Left: Title page. Right: Plate 9

Miniature Collector's Cabinet (Possibly Nuremberg: After a composition by Bernard Salomon, ca. 1600)

This remarkable collection is available for Museum visitors to explore by visiting the Department of Drawings and Prints.

Thanks to Femke Speelberg, Associate Curator, Historic Ornament, Design, and Architecture, Department of Drawings and Prints, who made several helpful contributions to this post.