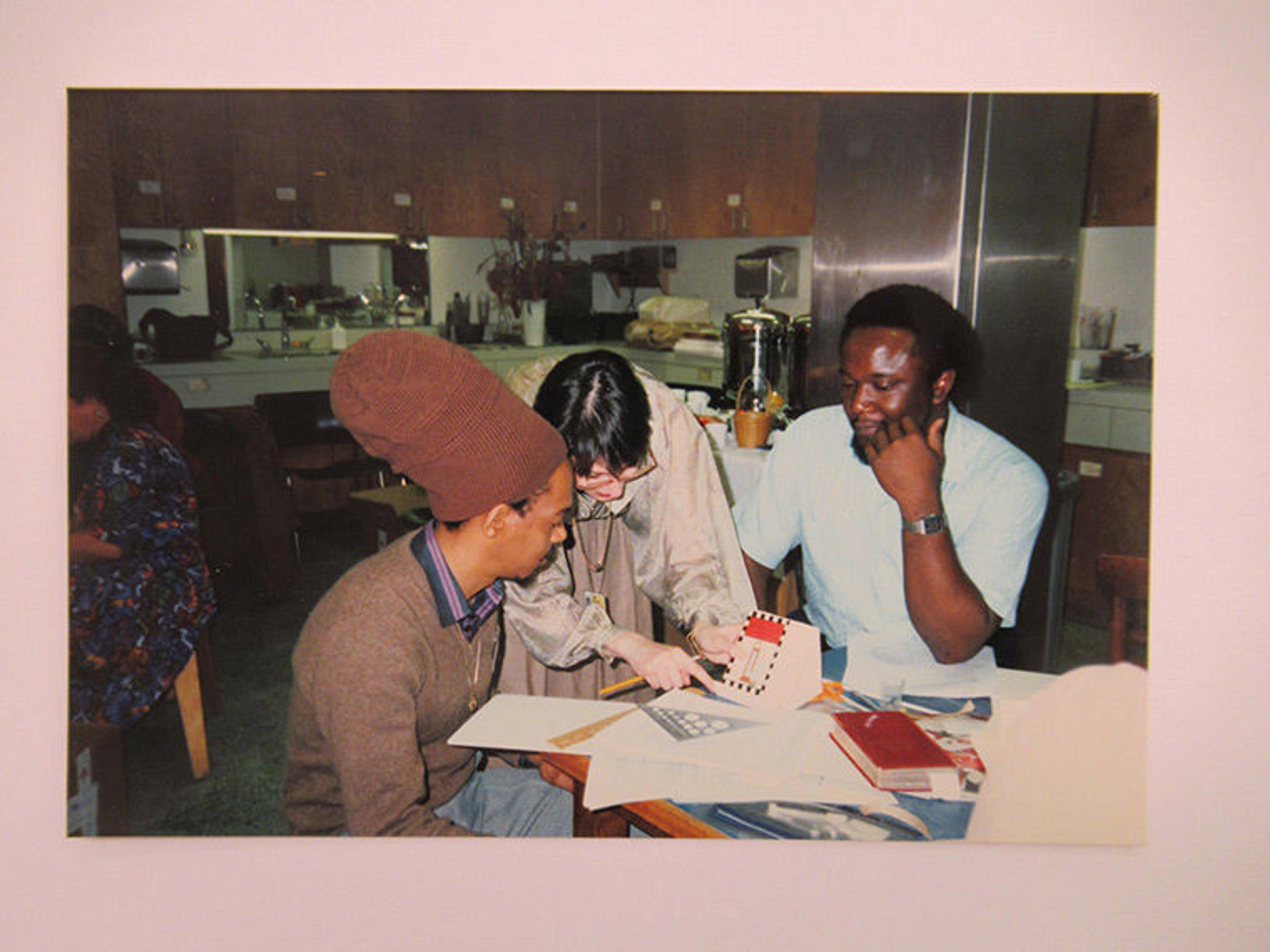

Ron Fein (left) and Friend of Thomas J. Watson Library Eileen Hsu (right) in the library, 1987

Just as The Met is celebrating its 150th anniversary, so too is the library. And to commemorate the occasion, we've created a series of blog posts that explore the history of The Met's research library (as well as some of its departmental libraries). This particular post will focus on some of the individuals who have been a part of this history for the longest periods of time—five librarians who, collectively, have worked in the library for over 150 years: Ross Day (thirty-nine years), Mindell Dubansky (thirty-eight years), Ron Fein (thirty-seven years), Holly Phillips (twenty-five years), and Min Xu (twenty-one years).

I've interviewed each about their long careers at The Met, and below are some of the memories they share, as well as some photographs they still hold onto after all these years.

Interview

William Blueher (WB): When did you begin working in the Museum? How old were you? Where were you at in your life?

Ron Fein (RF): I started working at the Museum in July 1983. I was eighteen years old and I had just graduated high school with no direction.

Ross Day (RD): I began working the day after Ronald Reagan was first elected president—November 5, 1980. I was a few days shy of my twenty-fourth birthday. I had just moved back to New York City to go to Columbia University's School of Library Service—a decision I deferred when I got the job at The Met. I had previously worked in a public library for two years, and at an art slide library for two years before that. As far as working in libraries, the die was cast.

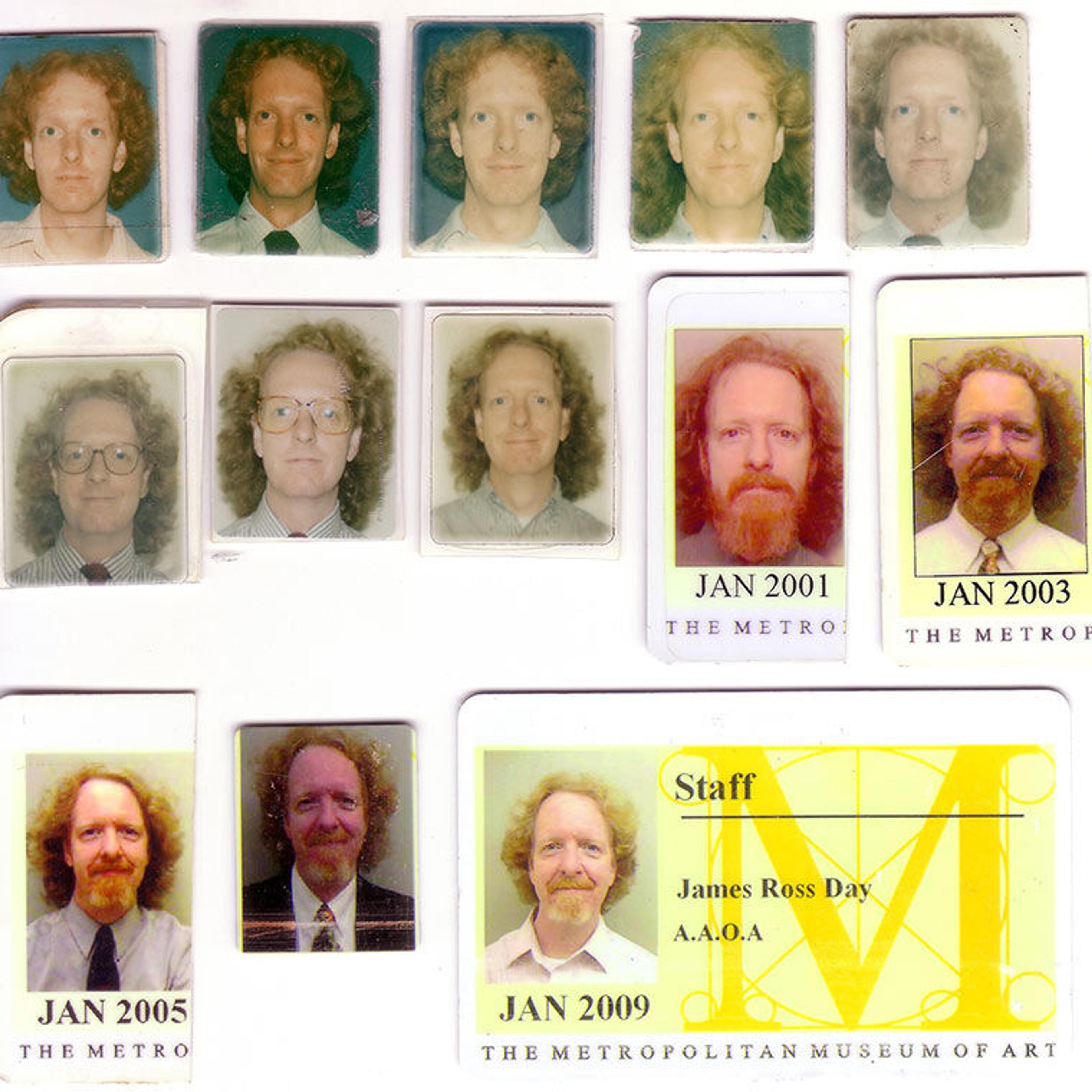

The many Met IDs of Ross Day

Mindell Dubansky (MD): I had heard that this job was open but they had been interviewing while I was in England. Just before I came back to the states, I received a message from the Chief Librarian, William Walker, to come in for an interview when I got back. I came the DAY AFTER I got back to New York and showed Mr. Walker my portfolio. He told me I would have to wait to hear, about two weeks, so I immediately took another job with Carolyn Horton who had a private conservation business. Well, he called me the very next day and I hung the phone up on him as I was so shocked. A friend who I was staying with asked me "who was that?" I told her it was the librarian from The Met. She said "you hung up on him, call him back!" So that is the short story of how I got my job.

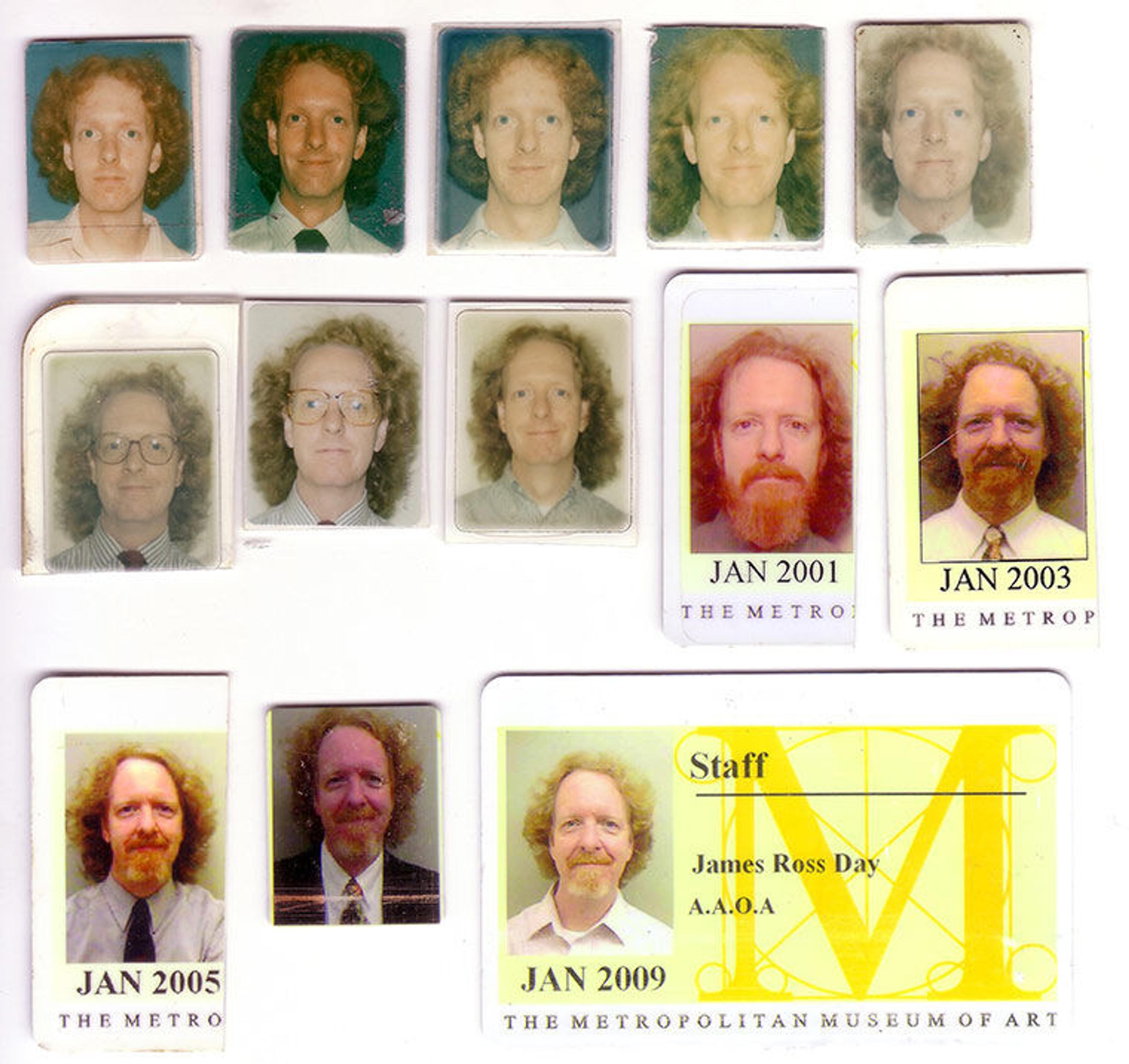

Mindell Dubansky in a Met shopping bag ensemble (skirt, top, hat, and jewels made from admission buttons) was a collaborative effort by book conservation staff and volunteers. Its purpose was as a costume for Dubansky to wear as an auctioneer at the first Dieu Donné Papermill auction in 1994.

Holly Phillips (HP): When my fall volunteership at the Costume Institute was completed and after making the decision to apply for an M.A. in art history at Columbia University, I sought a part-time job in the Museum. I looked at "the board" in the staff cafeteria—where the available jobs were located then—and a part-time job in acquisitions in Watson Library stood out. I loved books and art history, why not apply! When I told my friends in The Costume Institute about my interview in Watson, they said "how wonderful, everyone in Watson is so nice! It's a great place to work!"

WB: Tell us about a particularly memorable colleague.

MD: When I came to the Met, I inherited a volunteer named Felicia Dautermann. She was the wife of Carl Dautermann, a long-time curator in ESDA (Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts) and also the curator of the Campbell Soup Museum, which seemed funny to me. She was outrageously smart and amusing and intensely devoted to Mr. D (all 3 of their daughters became art historians). Her job was bookplating. This meant that she was one of the first to see the newly acquired books. Every day she was there (I think Tuesdays or maybe more) Mr. D would come by in the afternoon and she would have selected the books he would be interested in. So, I quickly realized that they had a little racket going and he was the first to check out all of the books before anyone else could see them. That was pretty resourceful. Over the years I became close to them. Mr. D was an old-fashioned gentleman and he would always stand up when I came to the table in the cafeteria and at the end of the meal, he would ask "may I get you an ice cream." What's not to love?

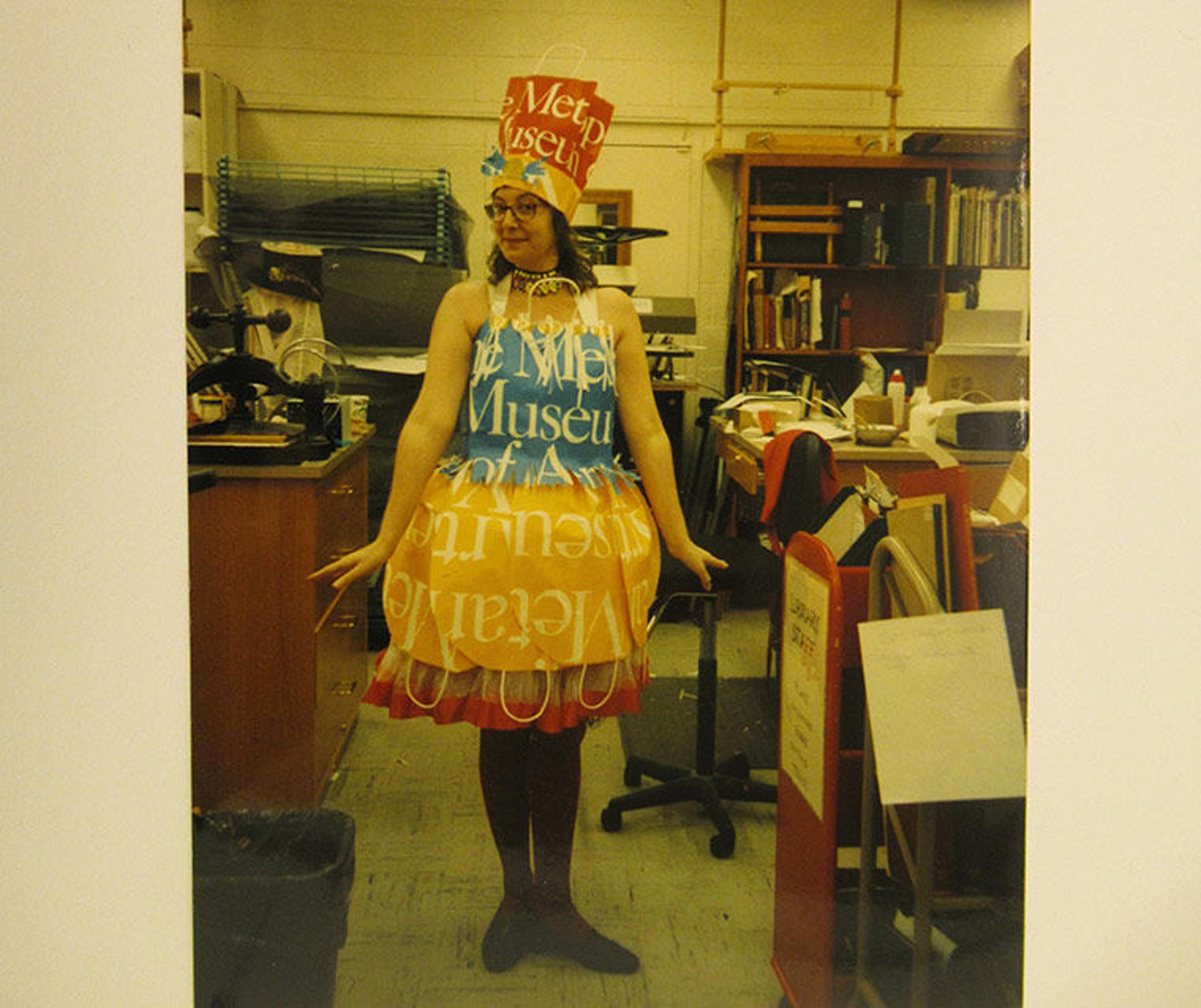

The bindery in the 80s, featuring volunteers and staff. From left to right, Paula Schrynemakers, Paula Beardell, Mindy Dubansky Katy Lethbridge and Adeline Frelinghuysen. Middle-front, is Mrs. Felicia Dauterman, our first volunteer who had been at the Museum since the 1940s. She did the bookplating and reviewed new acquisitions on behalf of for Mr. Dauterman, who was a curator in ESDA.

RD: Well, there have definitely been a host of characters among my library and Museum colleagues. For us long-timers, just the mention of their names is enough to evoke memories, still vivid long after they've left the Museum. When I began in AAOA (Department of the Art of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas), Douglas Newton was its chairman. Douglas was a very tall, wild-haired, soft-spoken (with a mild British accent) and wickedly droll presence in the department, who had a habit of looming up very quietly while your back was turned. He always seemed as if he'd much rather be in the wilds of New Guinea, in shorts and a bush hat, discussing the complexities of wood carving with local artists. Some of his witticisms are even now probably too risqué or offensive to repeat, however.

RF: Albert Torres was kind of crazy, but in a really nice way. We had a unique experience with ducks in the courtyard outside the windows in Watson. A duck and six ducklings got stuck there. We brought in a small pool and filled it with water each morning and fed them. The Central Park Conservatory came and picked up the ducks at some point to take care of them.

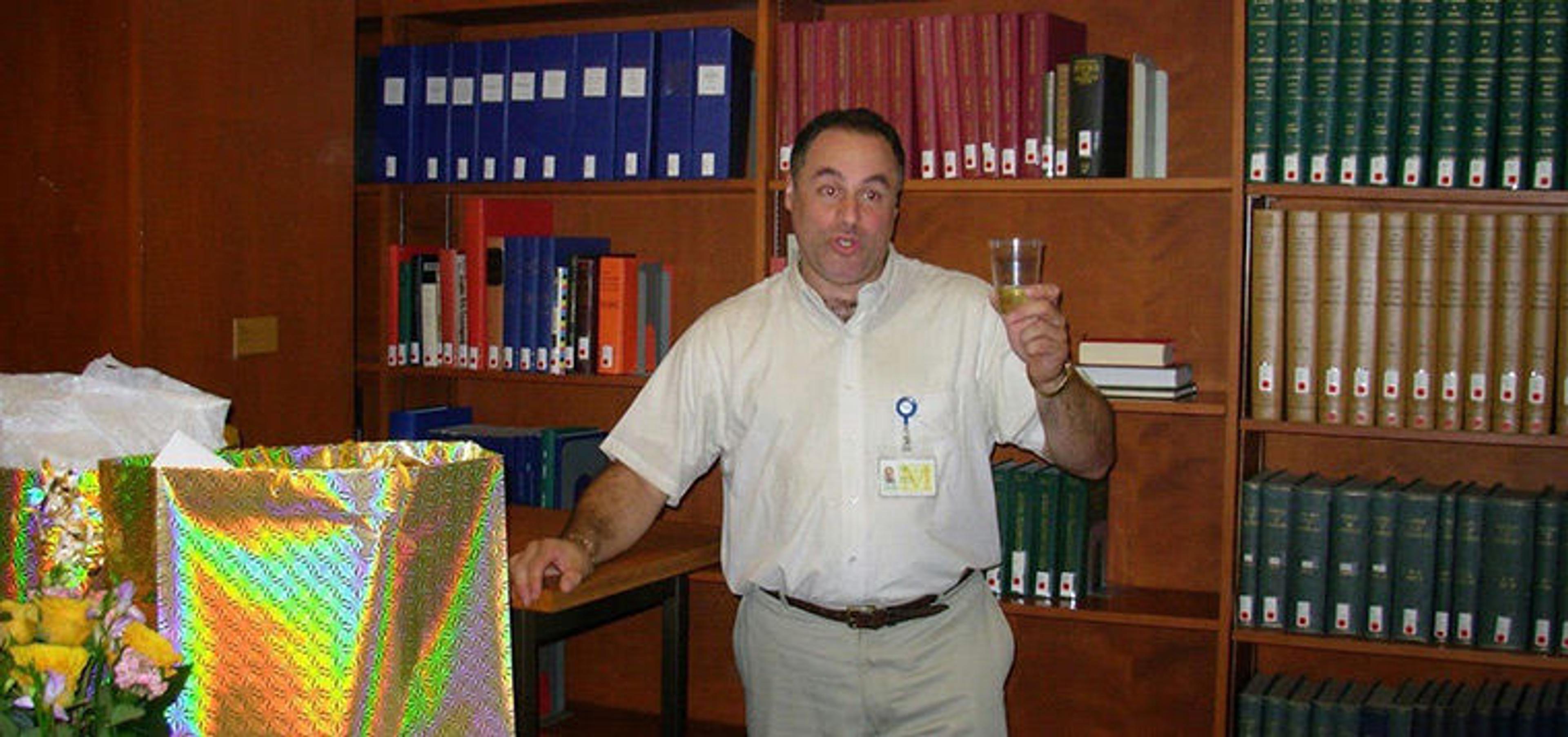

Ron Fein celebrating in Watson Library, circa 2015

WB: What is most different between working in the Museum today and when you began?

HP: The Museum used to be closed on Mondays which was, of course, very different. Because the Museum was empty, there was a distinct "Monday feel," a hush throughout the Museum when staff would roam the galleries seeing the exhibits and studying the permanent galleries. Every Monday morning, the Lila Acheson Wallace flower urns were re-filled with their exquisite bouquets, and pretty, stray flowers would fall onto the Great Hall marble floor as they were being arranged.

Holly Phillips in the Great Hall in 2014. Photo by Maggie Phillips

MD: I guess it was more of a small town when I started. I used to go visiting people regularly as I worked alone for a long time. I was even comfortable dropping in at the President's office (Mr. McComber?) and saying "Hi." I was comfortable visiting anyone, so it was more friendly and open than now in a casual way. The internet and computers have made a huge difference in how people work. The flower arrangements were more extravagant. I could go on about this. In my area of interest, institutional support for conservation, preservation, and collections management has grown hugely.

Book conservation conducted several workshops in collaboration with the Education Department's School Programs teaching public school teachers book arts, circa early 1990s.

RD: Speaking for the libraries, two things: automation and the sense of professionalism. Okay, three things: automation, professionalism, and the pace of work. Perhaps because I worked in a department (AAOA)—most of whose members had previously worked in the Museum of Primitive Art—there was feeling of its being an enclave within the Museum with its own habits, rules, style, and pace of work, all of them quite casual. It was a great opportunity to experiment and grow professionally.

Ross Day with former Goldwater Library staff (from left) Leslie Preston and Joy Garnett on the The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden, circa 2004

WB: What, if anything, do you miss about the card catalogue?

RF: It really made it look like a library, and it was unique. In those days, people would go right over to the card catalogue and search for books. The card catalogue gave Watson an antique and special feeling. After the card catalogue was gone, it created much more space in Watson, but I always miss the feelings it created when we had it there.

RD: I rather enjoyed typing up catalogue cards, strangely enough: sticking the top edge of the card under the card-holding platen, rolling it up to the first line, and typing away. I'd rather not think about how many cards I actually made this way.

Min Xu (MX): I don't miss the card catalogue at all.

Min Xu (center let) with former Watson staff (from left) Jennie Pu, Barbara Reed, and Nancy Mendel in the Temple of Dendur

WB: Have you held onto any Watson Library memorabilia over the years?

RF: Oh my God. Have I held onto anything? I have those old admissions pins that you would clip onto your clothes. I have the pneumatic system tubes that we would send into the stacks with book requests before our computer paging system. I have a card catalogue drawer I was given, and I have old wooden boxes that were used for scrap paper at one time. I also have a lot of pencils that say Watson Library from a batch we never used. Plus, a lot of other meaningful memorabilia like old handwritten paging slips.

HP: The book weight—sometimes known as snakes, which we called them—which I was given when I first started working as a Library Assistant in Acquisitions. I made a calico cover for it and treasure it to this day. Behind my door is a striking red Watson apron designed by Mindy Dubansky printed with cheery cherubs. I have had it for years and wear it with great happiness.

From left: Min Xu, book conservator Yukari Hayashida, and Holly Phillips in 2019

MD: I have some jewelry made from old buttons, many vintage Met post cards and photographs, and some of my home bindery furnishings came from my old studio before renovation. I have collected posters and catalogues of the artist book shows I had in the 80s in the Library. I must have more, but never really thought about it.

Staff and volunteers of the bindery in the late 80s, early 90s. Left to right: [unknown], Paula Schrynemakers, Kathy Greenberg, Judith Hanson, and Mindell Dubansky

MX: Yes, quite [a few things]. Tote bags, a Museum photo [I] got from a staff raffle, and many other things from the gift store.

WB: What is your favorite part of the Museum?

MD: The stacks of course! Other than that, the big room in AOAA with the Asmat canoes and poles. There are a million other places I love but those are the first to come to my mind.

RF: I would say the Petrie Court. I love it because the wall was originally the outside of the Museum and they added onto it since then. You can see Central Park from there, and it is a really beautiful space. If you're in Petrie and you're looking straight out into the Medieval hall, you can see the Christmas tree during the holidays.

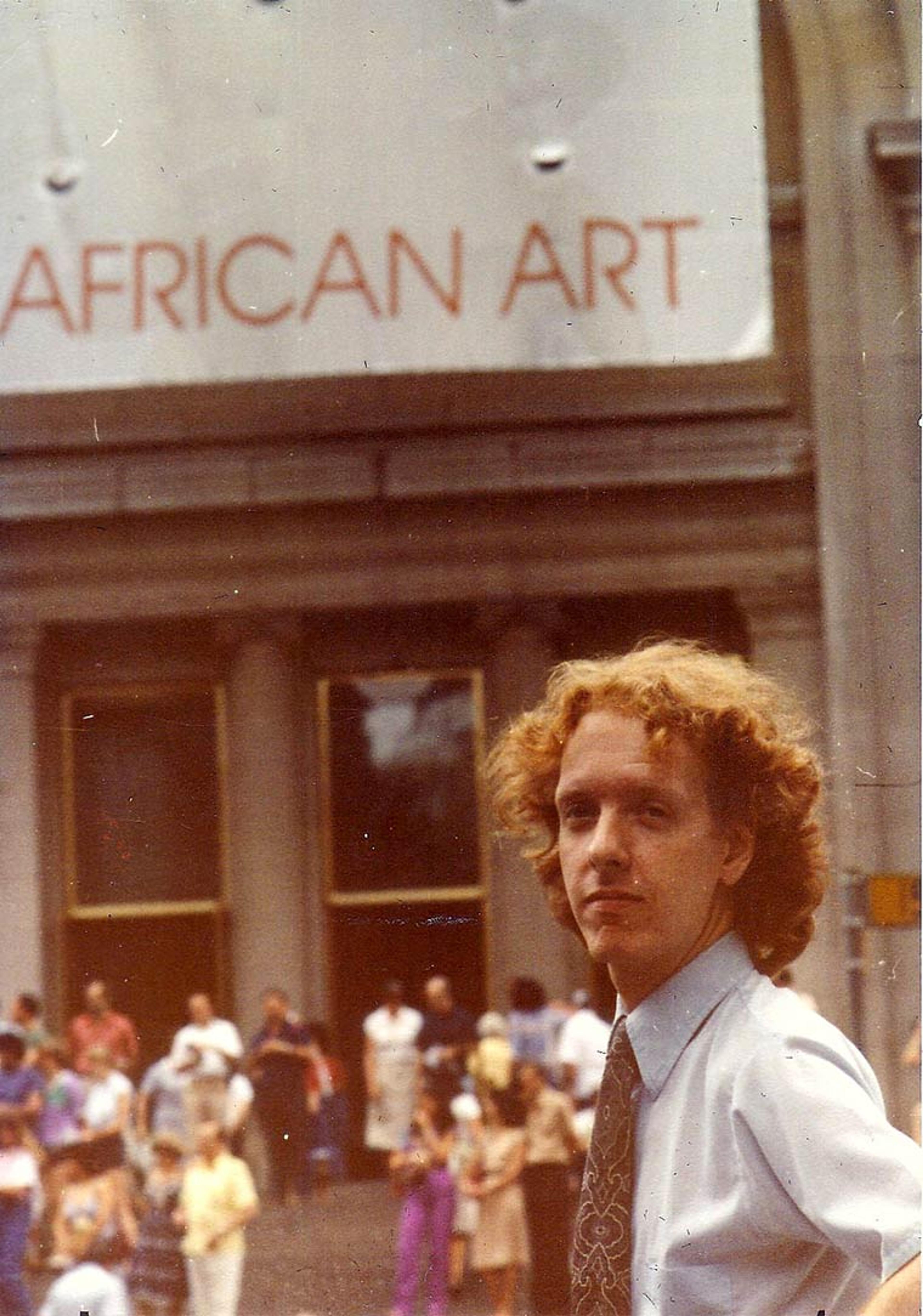

Ross Day in front of The Met, circa 1988

RD: It's hard to beat coming to the Museum every day, even if there's never enough opportunity to explore it fully. After thirty-nine years there are still corners of the building I've never been to. One of the enviable pleasures of walking through the galleries is being arrested by a work of art you'd never noticed before, stopping to take time to give it its due, and then heading back toward your original destination. You wonder sometimes how much attention any one piece has gotten from other Museum visitors, given how much there is to see in the Museum. I always feel I've done a good deed by stopping to admire the work, justifying the work countless Museum employees have done to acquire, install, and maintain it.