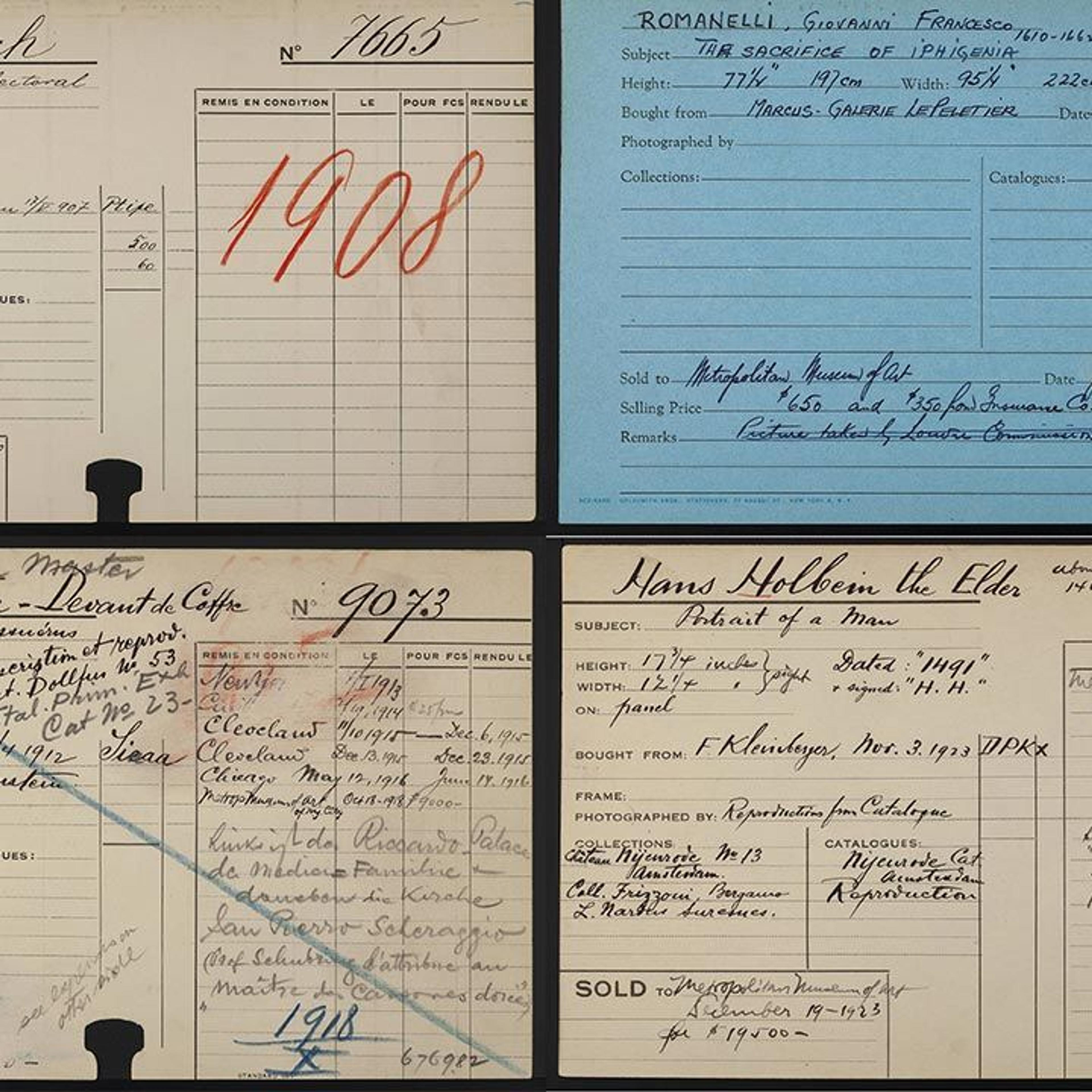

Left: Giovanni di Paolo (Italian,1398–1482). The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise (1445), 1445. Tempera and gold on wood, 18 1/4 x 20 1/2 in. (46.4 x 52.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.31). Right: Stock card 15165 for Giovanni di Paolo, Paradise Lost, 1917, F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc. Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise was painted in 1445 by the Sienese master Giovanni di Paolo. The artist cleverly merged two scenes from the Book of Genesis on a single panel intended for display in a polyptych setting in the Church of San Domenico, Siena. The complete work, referred to by art historians as the Guelfi Altarpiece, was long ago broken up and dispersed. Several large panels are now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, and in The Met are a compact scene of saints and angels in Paradise and this Creation and Expulsion. Details about the provenance of the latter are recorded in early twentieth-century business records of F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc., which are newly accessible online via Watson Digital Collections.

Art dealer archives present us with many surprising kernels of information. The Kleinberger inventory card for this picture alludes to John Milton’s epic poem by titling it Paradise Lost. It was once owned by Camille Benoît, a French composer and Louvre Museum curator depicted in an 1885 Henri Fantin Latour painting Around the Piano, now in the Musée d’Orsay. In January 1917, as battle raged across Europe, Kleinberger sold the panel for $9,000 to the American banker Philip Lehman. A note on the stock card cautioned that the painting was “to be delivered after the war.” Eventually, it was shipped safely to the Lehman family townhouse on West 54th Street in New York City and joined a renowned art collection cultivated by Philip Lehman and his son Robert. When Robert Lehman died in 1969 he bequeathed to The Met more than 2,600 objects, including Creation and Expulsion, which now hangs in a quiet corner of the Museum in gallery 956.

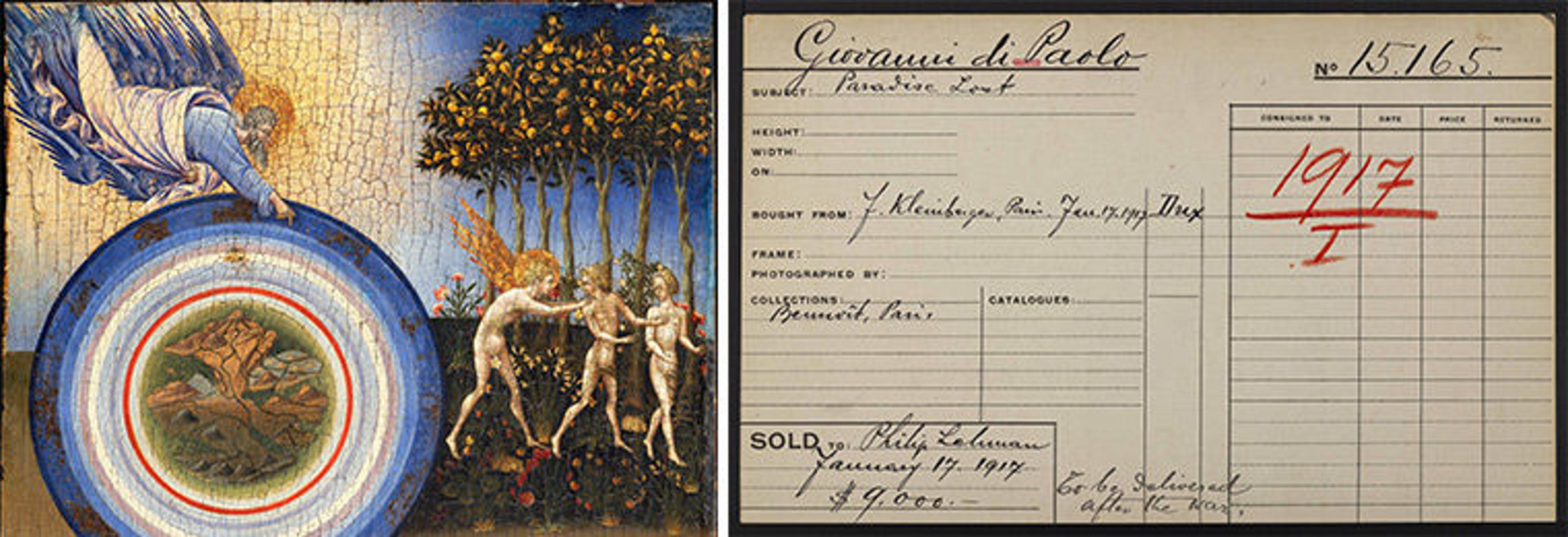

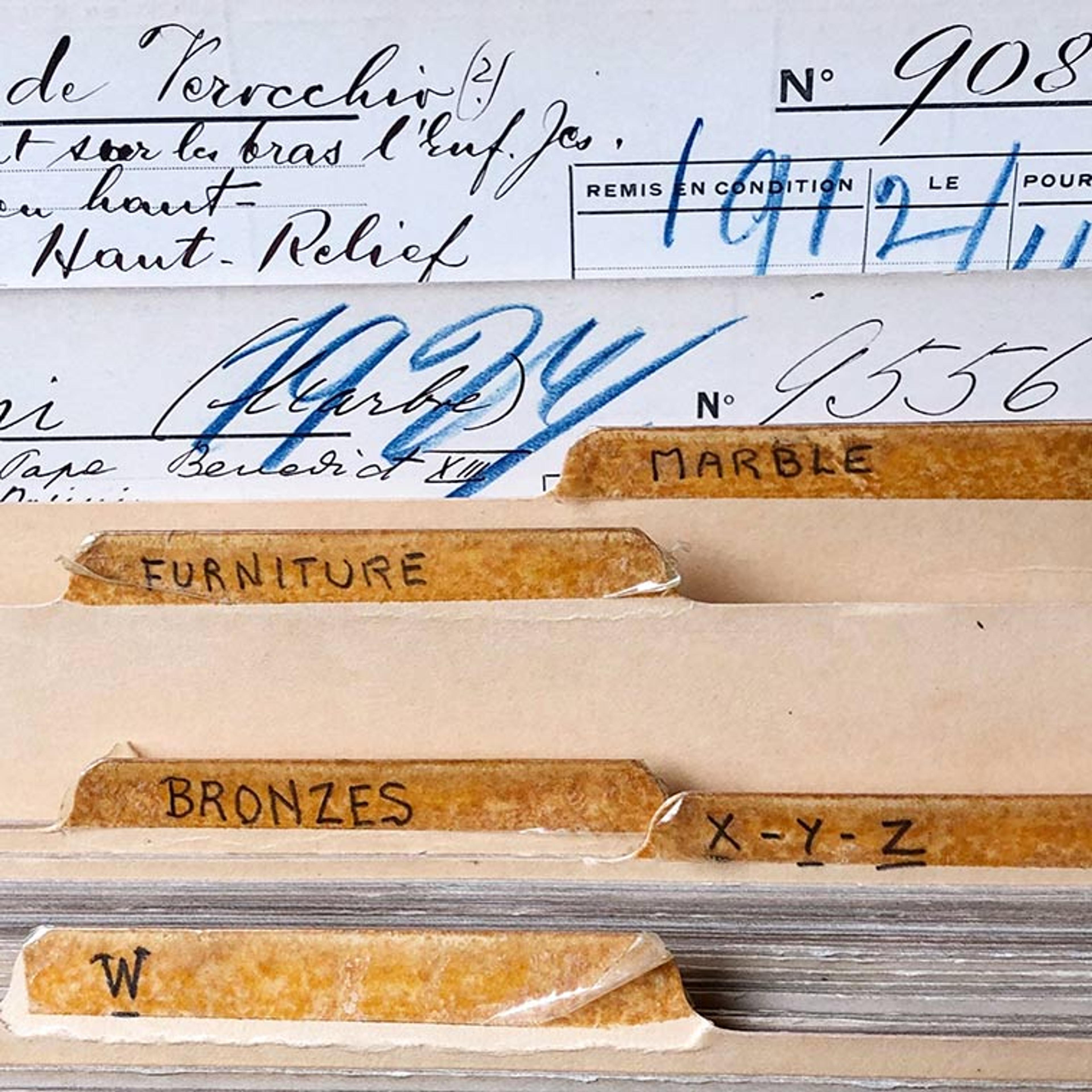

F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc. Records, European Paintings Department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by the author

In the twenty-first century, internet access to digitized historical documents enables curators, archivists, students, or anyone at all, to intensively research complex ownership histories like that of Creation and Expulsion. With nothing more than a good Wi-Fi connection, it is possible to explore a fast-growing, online corpus of art dealer archives, collectors’ papers, military and government documents, and museum business correspondences. In the pre-internet era such investigation was possible by those able to gain access to the original, analog sources. The hard copy F. Kleinberger Galleries stock cards, for example, were for many decades viewable by special appointment in The Met’s Department of European Paintings offices. The story of how they came to the Museum and have now been digitized to reach a global audience is perhaps as interesting as the provenance of Giovanni di Paolo’s masterpiece.

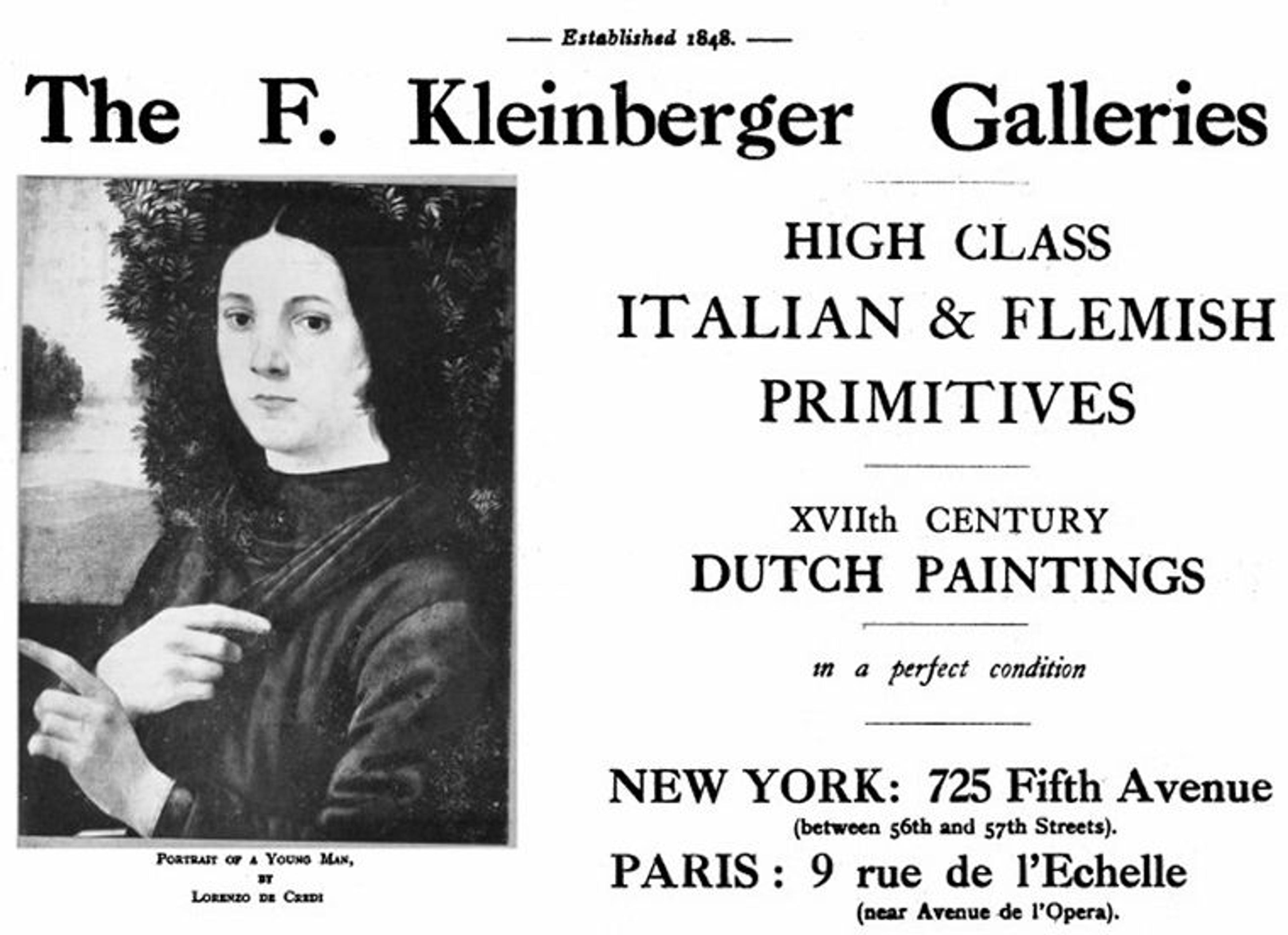

F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc. advertisement in The Burlington Magazine, February 1924, retrieved via JSTOR

F. Kleinberger Galleries was established in 1848, possibly in Paris, and over 120 years dealt old master paintings, and to a lesser extent drawings, sculpture, decorative arts objects, and furniture, to clients in Europe, the United States, and South America. The early history of the firm is a bit murky, but it was apparently founded by Franz Kleinberger, who was succeeded by another Franz, most likely a son, who is referred to in some documents as Francois. In the twentieth century, this second Franz expanded the business and shifted its sales focus to the United States. His son in law, Emil Sperling, helped open a permanent New York branch in 1910. American sales initially focused on northern European paintings, though by the 1920s Kleinberger routinely handled Italian pictures and sought advice about many of these from renowned expert Bernard Berenson.

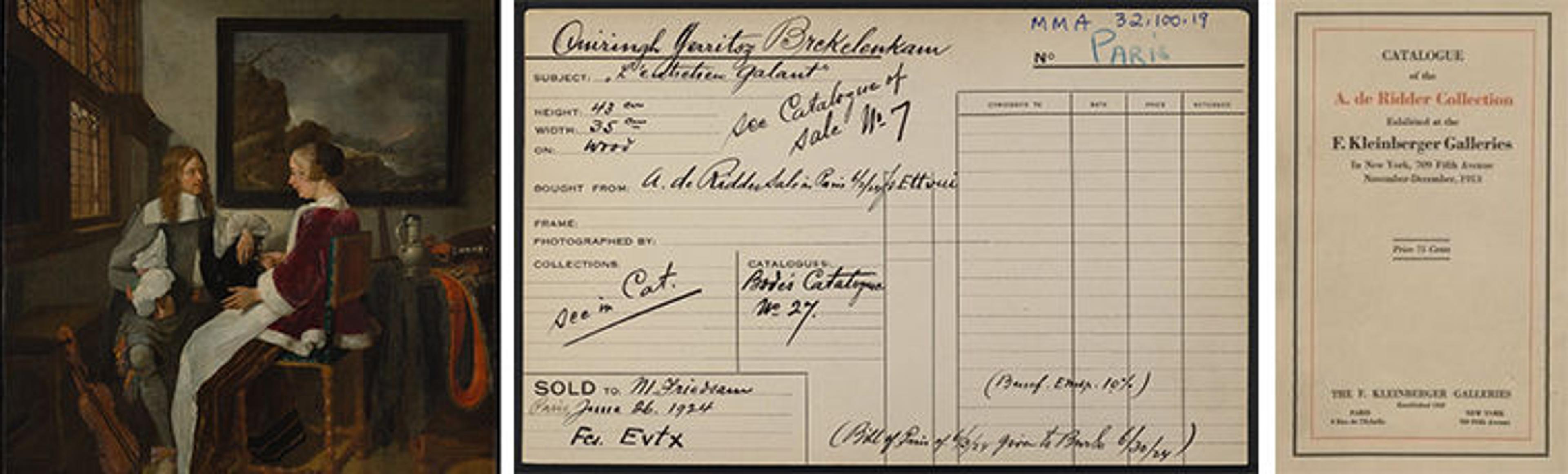

Left: Quirijn van Brekelenkam, (Dutch, 1622–ca. 1669). Sentimental Conversation, early 1660s. Oil on wood, 16 1/4 x 13 7/8 in. (41.3 x 35.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931 (32.100.19). Center: Stock card for Quirijn van Brekelenkam, Sentimental Conversation, F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc. Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Right: Catalogue of the A. de Ridder Collection (New York: F. Kleinberger Galleries, 1913), retrieved via Internet Archive

Kleinberger frequently bought and sold pictures in shares with other prominent dealers, notably Arnold Seligmann Rey & Co., Julius Böhler, and Adolphe Loewi. Kleinberger played an important role in the formation of the collection of the Belgian-German businessman August Cornelius de Ridder and marketed it to American buyers in 1913. Some of these pictures, such as Quirijn van Brekelenkam’s Sentimental Conversation, later made their way to The Met. Many important American clients were bankers, including Jules Bache, Walter C. Baker, Philip and Robert Lehman, and Mortimer Schiff. The attorney John G. Johnson and financier J. P. Morgan were other notable customers.

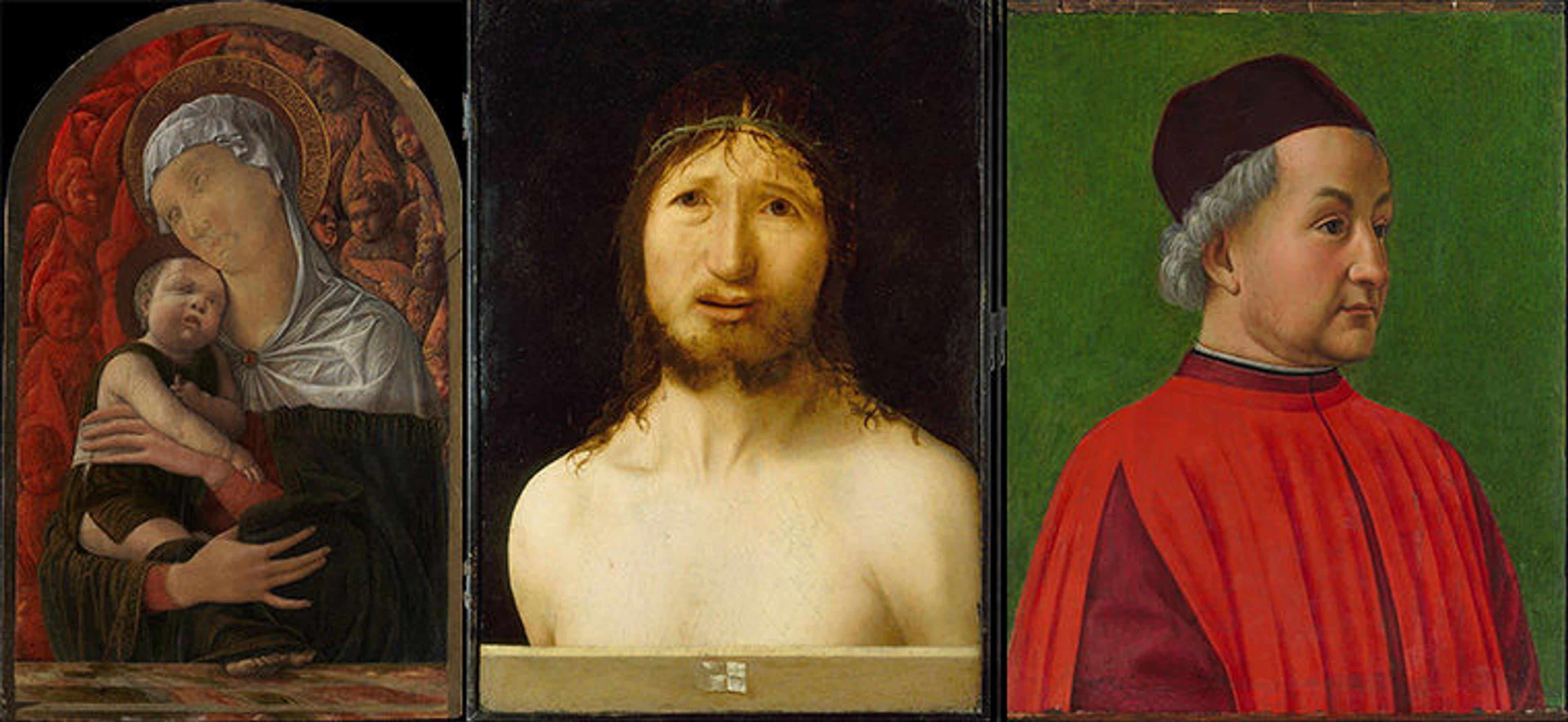

Three pictures sold by F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc. to Michael Friedsam, who bequeathed them to The Met (from left): Andrea Mantegna, Madonna and Child (32.100.97); Antonello da Messina, Christ Crowned with Thorns (32.100.82); Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portrait of a Man (32.100.67); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931

Kleinberger sales to the department store magnate and art collector Benjamin Altman and his business successor Michael Friedsam were especially lucrative. Major works sold by Kleinberger to Altman that later came to The Met include Hans Memling’s Portraits of Tommaso di Folco Portinari and Maria Portinari and Andrea Mantegna’s Holy Family with Saint Mary Magdalen. Masterpieces that Friedsam bought from Kleinberger and bequeathed to the Museum include another Mantegna, Madonna and Child, Vermeer’s Allegory of the Catholic Faith, Rogier van der Weyden’s Portrait of Francesco d’Este, Antonello da Messina’s Christ Crowned with Thorns, and Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of a Man. Bernard Berenson advised on many of these deals, and his letters to Franz Kleinberger, now at the Getty Research Institute, provide fascinating insight into his influential role in forming the Friedsam collection. Other exceptional pictures now in the Museum that were once dealt by Kleinberger include several in the Lehman Collection, such as the di Paolo discussed earlier, Francisco Goya’s Condesa de Altamira and Her Daughter, and the Jean Hey portrait Margaret of Austria. In addition to marketing art to private collectors, Kleinberger also sold pictures directly to museums, including The Met, Baltimore Museum of Art, Cleveland Museum of Art, St. Louis Art Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, and Detroit Institute of Arts. International museum clients included the Louvre and Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

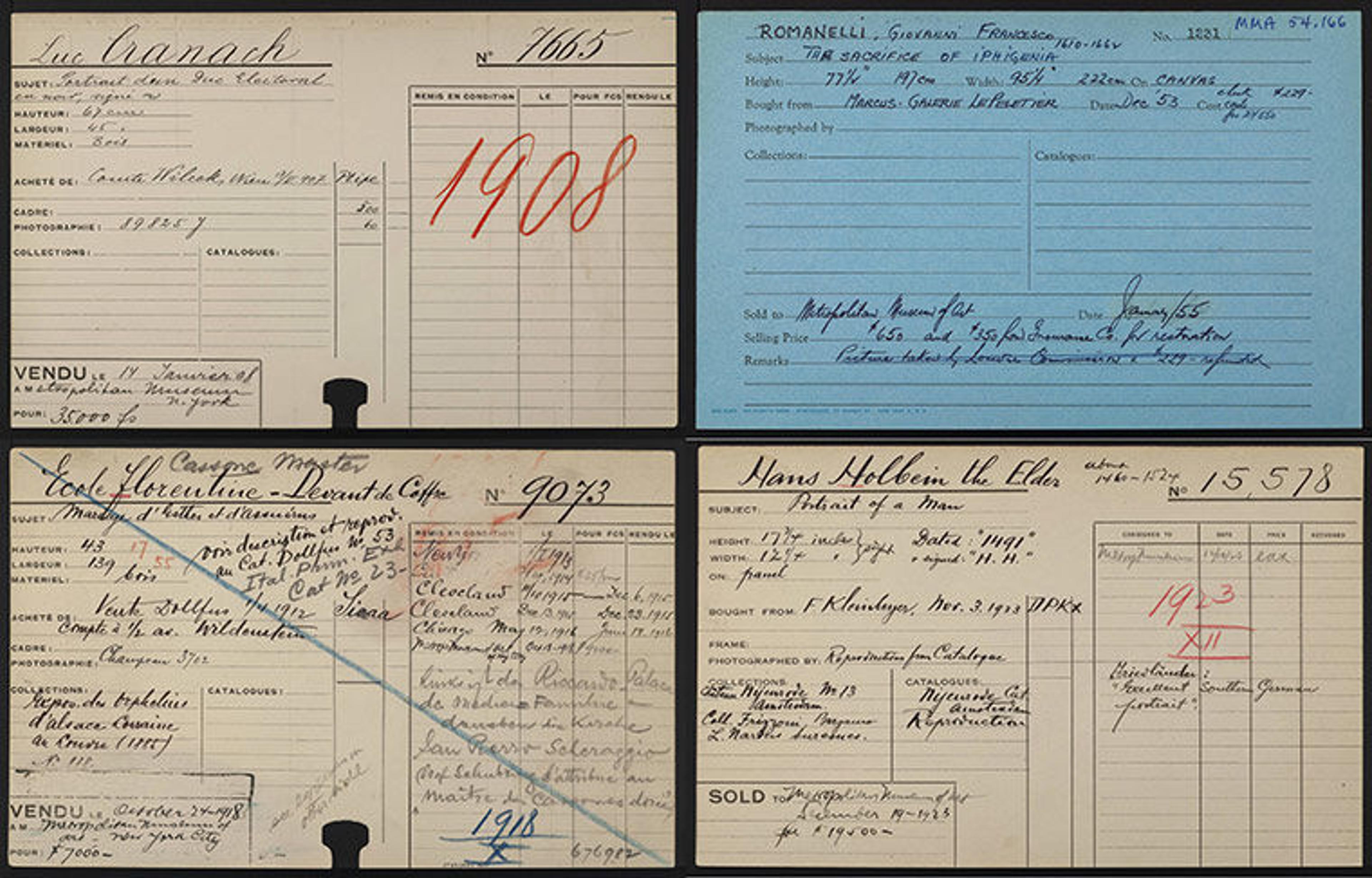

Stock cards for four paintings sold directly to The Met, F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc. Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Clockwise from upper left, accession numbers: 08.19, 54.166, 23.255, 18.117.2

In the years after Emil Sperling’s early death in 1930, his son Harry G. Sperling took a lead role in the business, becoming president in 1933. The New York gallery closed for a few years during World War II while Sperling served in the U.S. Office of Strategic Services. The Paris branch of the firm continued to operate during the German occupation under the name Galerie Garin and was directed by Allen Loebl, a Kleinberger relation associated with the business since at least the 1920s. Loebl’s role in a network of Paris art dealers who collaborated with Nazis by scouting and securing artworks for them is described in documents of the U.S. military Monuments Men. More research is needed on this part of the story, though there is scant evidence of substantial deals between Kleinberger-New York and the Paris operation under Loebl during the time of the German occupation.

Enthroned Virgin and Child. French (1150–1200). Walnut with gesso, paint, tin leaf, and traces of linen, 27 x 11 1/4 x 11 in. (68.6 x 28.6 x 27.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection and James J. Rorimer Memorial Fund, 1967 (67.153)

After the war, Harry Sperling reopened the New York gallery, reestablished other business connections in Europe, and began to sell some stock through a South American subsidiary managed by Nicholas Karger. During the mid–twentieth century, Sperling provided appraisal and authentication services to private collectors and acted as an intermediary for some outstanding Met acquisitions, including a Medieval French virgin and child sculpture, which arrived at the Museum in 1967. Harry G. Sperling died in 1971, and F. Kleinberger Galleries closed soon after. Sperling bequeathed to The Met many drawings and paintings, an endowment to support purchases of European drawings and prints, and more than 6,000 Kleinberger Galleries stock cards representing artworks bought and sold from the 1890s to the 1970s.

Each stock card pertains to a unique artwork and includes the name of the artist, a title, source of acquisition, name of the buyer from Kleinberger, prices, and in some cases ex-collection or bibliographic data. They are hand written, mostly in English or French, but a few dozen are in German. These documents, together with a collection of Kleinberger business correspondence now at the Getty Research Institute, offer a detailed record of the firm across seven decades. No archival record of the founding and nineteenth-century activity of Kleinberger has yet surfaced, and it is likely that much of that documentation was lost or destroyed during World War II.

The initiative to digitize The Met's Kleinberger stock cards was modeled on the Museums Brummer Gallery digitization project, completed in 2013. Met staff were inspired as well by colleagues at the Getty, the Archives of American Art, and elsewhere who have posted the records of dealers Jacque Seligmann & Co., Duveen Brothers, and Knoedler Gallery online. Luckily, imaging of the cards was completed shortly before the Covid-19 pandemic impacted New York. All are hand-written—many in a script that would challenge the capacity of optical character recognition—so to render them searchable key data fields were transcribed by a team of Met archivists, librarians, and others as a 2020 work-from-home project. Generous support for the project was provided by the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation.

The online collection is browsable and searchable by artist name, title, Kleinberger stock number, buyer, seller, and date. When a user clicks on a result, they are presented with recto and verso images of the card, and can themselves view additional, untranscribed, information about each artwork, or make interpretations of data that was sometimes difficult to discern and may have been approximately entered by the transcriber. The Kleinberger staff who long ago wrote out these cards were inconsistent in their spellings of names, use of acronyms, abbreviations, punctuation, price codes, and other idiosyncrasies that Met transcribers did not interpret or correct on the fly. Likewise, many artworks are represented in the database with artist attributions exactly as they were written on the cards decades ago, but which in the twenty-first century are questioned or rejected.

In art museums, where objects may reside for hundreds of years, knowledge about them accumulates slowly over time through the collective efforts of many people who look at them carefully, conduct scientific research, write catalogue entries, and explore archival evidence. The information created and saved by each generation that cares for and studies these objects is safeguarded in multiple locations—physical and now virtual—across these institutions. As art and accompanying metadata are made increasingly visible online, museums can open new conversations with a global audience about objects they hold in public trust. A challenge for the future of art institutions is to encourage dialogue and interactivity with their collections, and to document and preserve evidence of public engagement, so that new knowledge and interpretations may in turn be preserved and shared with future generations. We encourage you to become participants in this effort by exploring the F. Kleinberger Galleries Inc. records for your own research and enjoyment, and by sharing your discoveries with The Met community.