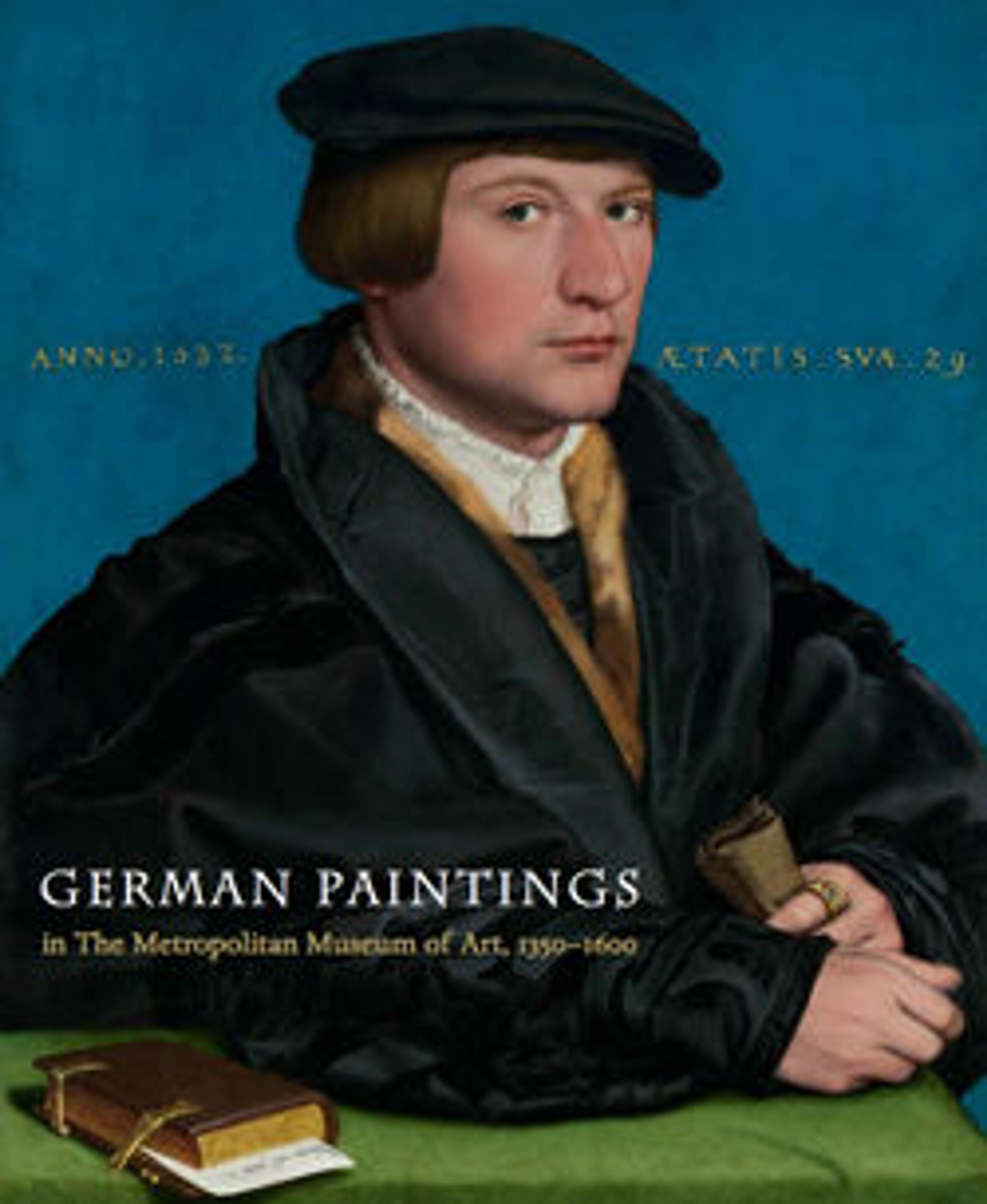

Johann (1498–1537), Duke of Saxony

In 1505 Lucas Cranach the Elder was appointed court painter to the Electors of Saxony at Wittenberg, serving successively Friedrich III, the Wise, Johann I, the Constant, and Johann Friedrich I, the Magnanimous. The sitter in this portrait, Johann, Duke of Saxony, Margrave of Meissen and Landgrave of Thuringia, was a member of the ducal or Albertine branch of the family as opposed to the electoral or Ernestine line. The bold design, dramatic color, and capricious but graceful outline of the costume are typical of the style Cranach developed as a portraitist to the court.

Artwork Details

- Title:Johann (1498–1537), Duke of Saxony

- Artist:Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, Kronach 1472–1553 Weimar)

- Date:ca. 1534–37

- Medium:Oil on beech

- Dimensions:25 5/8 x 17 3/8 in. (65.1 x 44.1 cm)

- Classification:Paintings

- Credit Line:Rogers Fund, 1908

- Object Number:08.19

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.