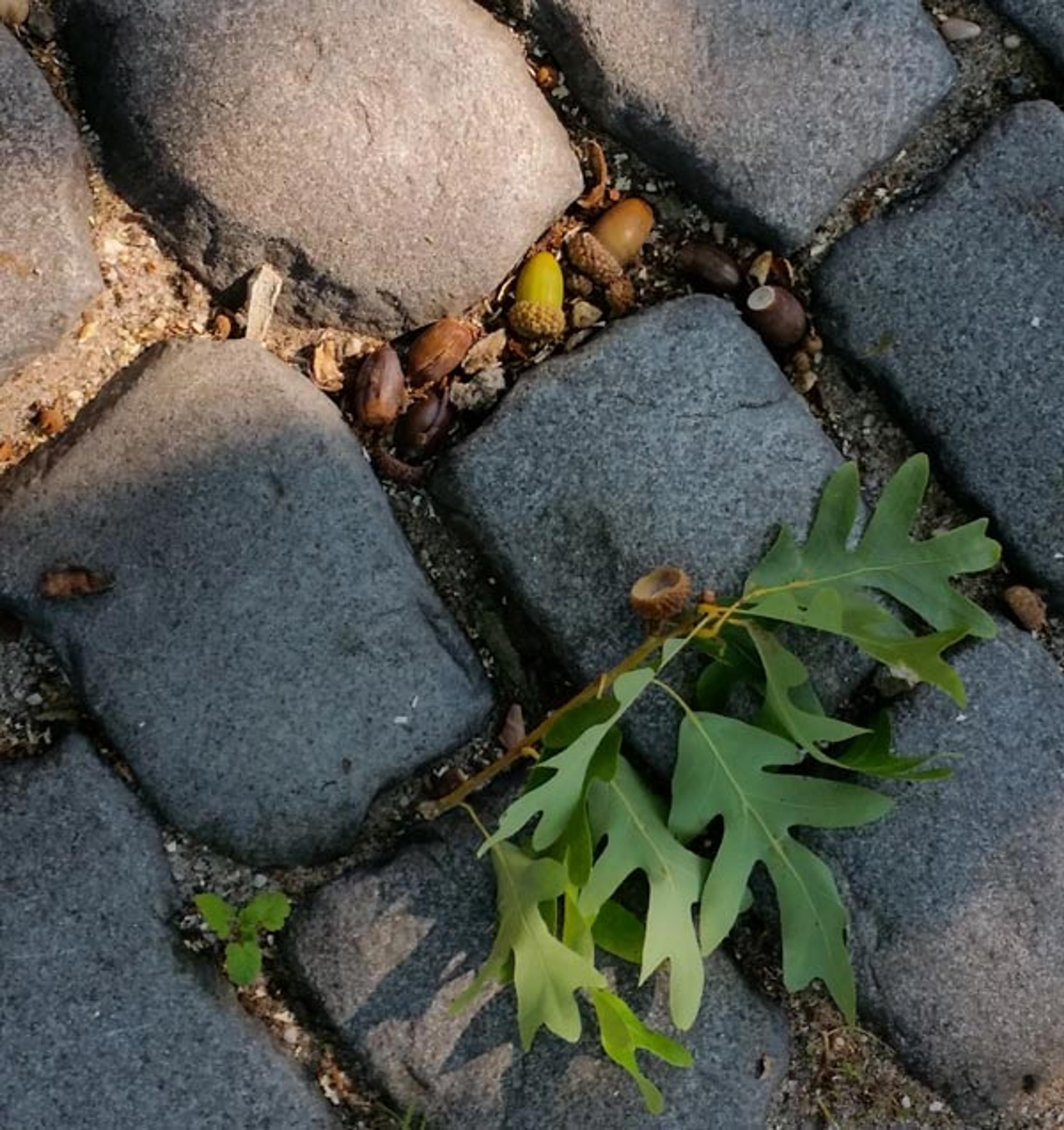

Leaves and acorns of the white oak in the cobblestone courtyard at The Cloisters. Photograph by Christina Alphonso

«In October, the sound of acorns falling from our oak trees, ricocheting off car roofs and crashing to the cobblestones, steadily and loudly increases. Etymologically, "acorn" is related to the Old English aecer (modern acre), as well as to Old French words for "nut" or "fruits and vegetables." Ultimately, acorn evolved to mean something akin to "fruit of the unenclosed land." Although the term originally referred to the nuts of any tree, we now use the word specifically for the nuts of oak trees.»

Although it may be a later replacement, note the tiny acorn that adorns the finial on this covered beaker at The Cloisters. Similarly, acorns often formed the ornamental knop on the handles of medieval silver spoons. Attributed to the workshop of Sebastian Lindenast the Elder (German, 1460–1526). Covered beaker, ca. 1490–1500. Made in Nuremberg, Germany. German. Copper gilt; Overall: 9 1/16 x 3 3/4 in. (23 x 9.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1994 (1994.270a, b)

Acorns, beechnuts, hickory nuts, haws, and rose hips are among the edible parts of woody plants categorized as either hard or soft mast. The oaks at The Cloisters have produced an abundance of acorns this fall as part of a natural cycle in which a bumper crop is known as a "mast year." Mast is an important source of food for foraging wildlife aside from the obvious squirrels.

In the Middle Ages, mast was a valuable food source for fattening domestic pigs. Jamón Ibérico de bellota is a prized Spanish cured ham still made from pigs fattened partially on acorns. In the New Forest, created as a royal English hunting ground in the eleventh century, the tradition of pannage continues, and pigs are still turned loose to fatten on mast in the fall. Although pigs can easily digest acorns, large amounts are toxic to horses and cattle.

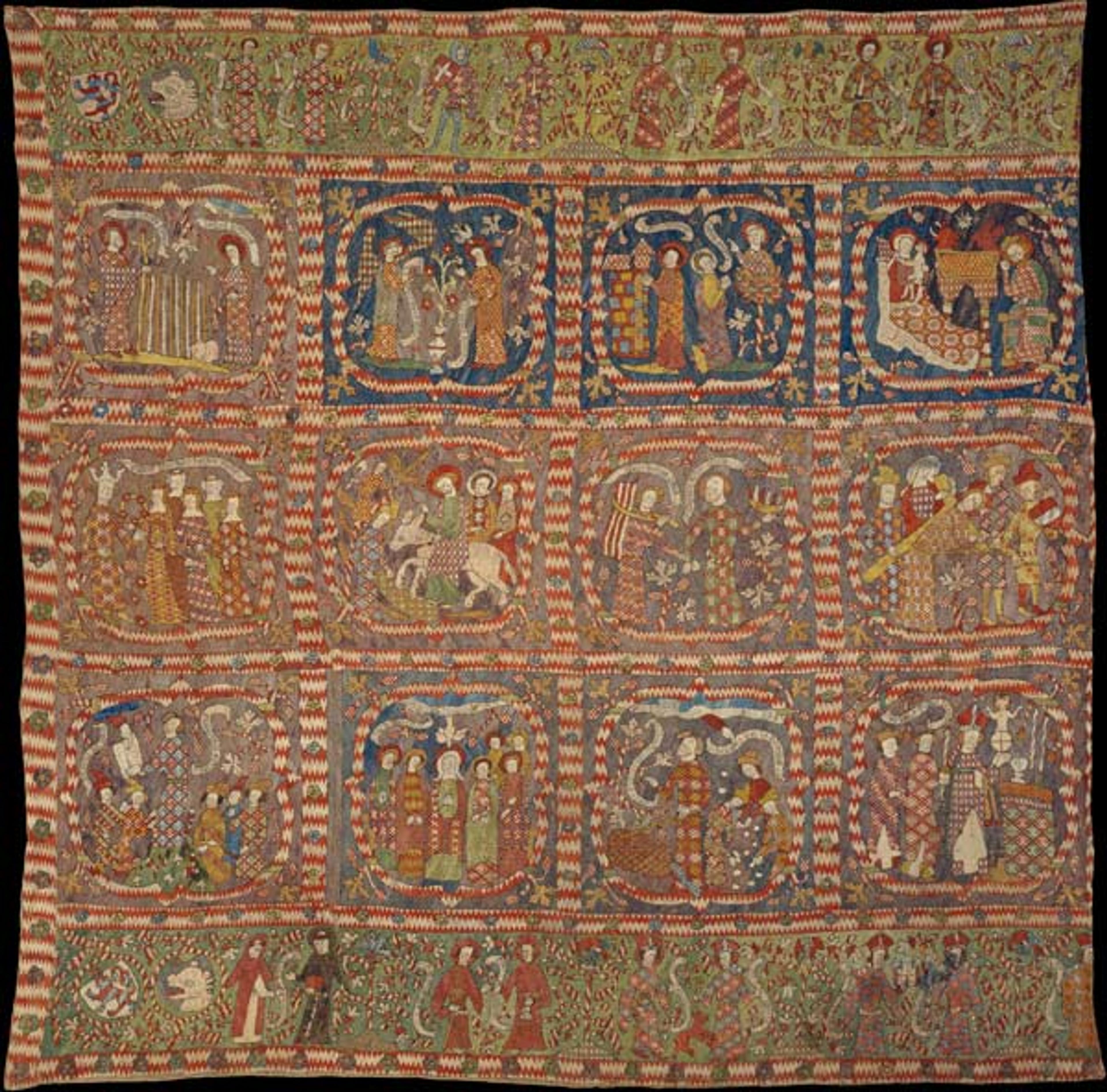

Top: Probably made by nuns, this fragmentary late fourteenth-century German embroidered hanging illustrates paired scenes from the Old and New Testaments. An extraordinary variety of brightly colored geometric patterns and stiches are demonstrated without any concern for three-dimensional representation. Embroidered hanging, late 14th century. Made in probably Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, Germany. German. Silk on linen, painted inscriptions; 63 x 62 1/2 in. (160 x 158.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. W. Murray Crane, 1969 (69.106). Bottom: A detail from the upper left corner of the embroidered hanging shows the heraldic devices of Hessen and Lichtfuss. The ends of the red and white cord linking the shields terminate in stylized oak leaves and acorns.

Long used as fodder for pigs, acorns were also consumed by humans during times of famine. They are easily stored for either purpose. Acorns are rich in protein, carbohydrates, fats, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and niacin, but are very bitter due to their tannin content. Pliny the Elder, among other sources from antiquity, noted that acorn flour could be used to make bread when necessary.

Acorns can be made palatable by repeated soaking in water to remove the astringent tannins, but they rarely feature in modern diets. They remain a traditional food for indigenous peoples of North America and in Korean cooking. The sweetest acorns are said to be from the holm or holly oak, common to the Mediterranean and western Asia.

Gold funerary wreaths like this one imitated wreaths of real leaves that were worn in religious ceremonies or given as prizes in antiquity. These astonishingly fragile objects were left in sanctuaries as dedications to the gods or were buried as funerary offerings. The oak tree was sacred to Zeus, representing strength and eternity, an allusion that carried over into the Christian era. Gold funerary wreath, 1st–2nd century A.D. Imperial. Roman. Gold; Other: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Wallace Phillips, 1957 (57.59)

Although oak bark was most commonly used for medicinal purposes, acorns were also said to be efficacious. Pedanius Dioscorides and Pliny recommended a decoction of either the skin or entire acorn to treat abdominal complaints and dysentery. The astringent properties of acorns were said to counteract vomiting, the spitting of blood, and inflammation. Maud Grieve, an acknowledged expert on medicinal plants, noted that a decoction of acorns and bark made with milk was used as an antidote for poison and that powdered acorn in wine was used as a diuretic.

Have you ever tasted anything made from acorns?

Sources and Additional Reading

Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food, edited by Tom Jaine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Grieve, Maud. A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic, and Economic Properties, Cultivation, and Folklore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, and Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses. 1931. Reprint: New York: Dover Publications, 1971.

Pliny. Natural History, Vol. 7, Books 24–27. Translation by W.H.S. Jones. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Prichep, Deena. "Nutritious Acorns Don't Have To Just Be Snacks For Squirrels." NPR, November 02, 2014.