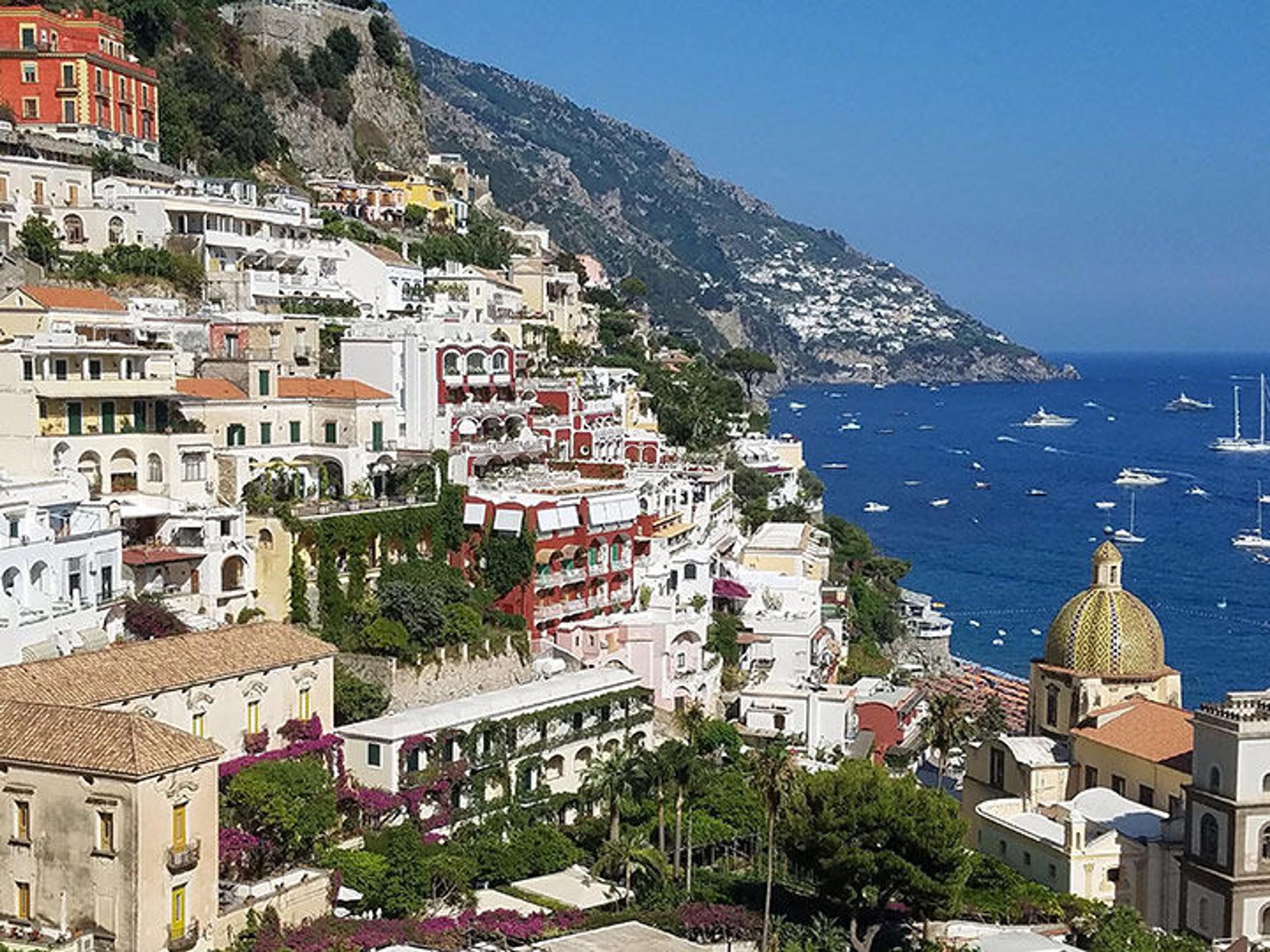

A view of the beautiful landscape a stone's throw from Salerno, Italy. All photos by the author except where noted

On Difficulty of Birth

Treatment. It is expedient for a woman giving birth with difficulty that she be bathed in water in which mallow, fenugreek, linseed, and barley have been cooked. Let her sides, belly, hips . . . be anointed with oil of violets or rose oil. Let her be rubbed vigorously and let oxizaccara be given in a drink and some powder of mint and wormwood, and let one ounce be given. Let sneezing be provoked with powder of frankincense placed in the nostrils. Let the woman be led about at a slow pace through the house.

This passage comes from The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women's Medicine, edited and translated by Monica Green. «The Trotula was once the most influential medical text on women's health and treatment, and is thought to have been written in the coastal town of Salerno in southern Italy centuries ago. Salerno was the hub of medieval medical learning, trade, and agriculture in the 11th and 12th centuries. This enchanting land was bountiful with grains, fruits, nuts, and water, and became known in distant lands as a place where the most knowledgeable medical practitioners resided and where "no illness was able to settle."»[1]

The lore of this famed work is captivating. The Trotula was believed to have been written by a female practitioner named Trota from Salerno's medical school. Trota was, in fact, a healer from Salerno, and is likely the author of On Treatments for Women, one of the three texts that make up The Trotula. However, the other two texts are anonymous and likely penned by male authors.[2]

The mysterious Trota sparked my curiosity into learning more about women's health during the Middle Ages. Treatments of particular interest were rose, wormwood, and pennyroyal.

Courtiers in a Rose Garden: A Lady and Two Gentlemen, ca. 1440–50. South Netherlandish. Wool warp; wool, silk, metallic weft yarns, 9 ft. 5 3/4 in. x 10 ft. 8 in. (288.9 x 325.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1909 (09.137.2)

The sweet smell of rose in pleasure gardens has been written about extensively, and rose is referenced as an important medieval flower. Both beautiful and symbolic, the flower holds a fragrance seen as beneficial and pleasing, perhaps even to a laboring woman. In Physica, the 12th-century visionary, mystic, and abbess Hildgard von Bingen writes of the rose:

Rose, and half as much sage, may be cooked with fresh, melted lard, in water, and an ointment made from this. The place where a person is troubled by a cramp or paralysis should be rubbed with it, and he will be better. Rose is also good to add to potions, unguents, and all medications. If even a little rose is added, they are so much better, because of the good virtues of the rose.[3]

Left: Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) grows in Bonnefont Herb Garden. A common roadside weed, this herb was once considered the "mother of herbs."

Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) is a silvery, astringent, and powerful plant, responsible for absinthe and a medieval remedy for headaches and fevers. Grown at The Met Cloisters in our household bed— along with other members of the genus Artemisia, which were known to be natural insecticides and strewing herbs—wormwood was also a remedy for "worms of the womb."[4] The name Artemisia derives from the Greek goddess of chastity, Artemis.

Less silvery and lacking wormwood's pungent odor is its relative, mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris). Referred to as the "mother of herbs" in Walafrid Strabo's famous 9th-century poem Hortulus, mugwort was reputed to ease childbirth, cleanse the womb, and restore a woman's "flowers."[5] A menace to most modern garden enthusiasts, mugwort was also believed to ward off evil and was a common ingredient in medieval gruit—an herbal mixture used to flavor beer.

The strong and acrid pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium) is not as mouthwatering as its relatives peppermint and spearmint. Found growing wild in moist soils near streams, this aromatic mint was once thought to be a natural flea repellent (pulex means "flea" in Latin). Like most plants in the Middle Ages, pennyroyal was considered a versatile herb. Known to be a powerful abortifacient, it was mentioned numerous times in The Trotula, from issues regarding a women's cycle, to pain of the womb. It was also noted as a remedy for cramps and colds.

Right: Pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium) is a potent herb. Like mugwort, it was used by midwives in the Middle Ages and is also grown at The Met Cloisters.

The Trotula is a fascinating look into women's health and treatment in the Middle Ages. My most recent travels took me through the seaside region near Salerno. With its fresh air, beautiful views, endless water, and fertile land, it was easy to see how it had become a center for healing all those years ago.

Cheers to Trota!

Notes

[1] Monica H. Green, The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women's Medicine (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 79.

[2] Green, "Who/What Is 'Trotula'?" Accessed at Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT). http://celt.ucc.ie/whowhat2008.pdf.

[3] Hildegard von Bingen, Physica: The Complete English Translation of Her Classic Work on Health and Healing, trans. Priscilla Throop (Vermont: Healing Arts Press, 1998), 21.

[4] Margaret B. Freeman, Herbs for the Medieval Household (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1943), 31.

[5] David E. Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield, Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition: An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Timber Press, 2004), 297.