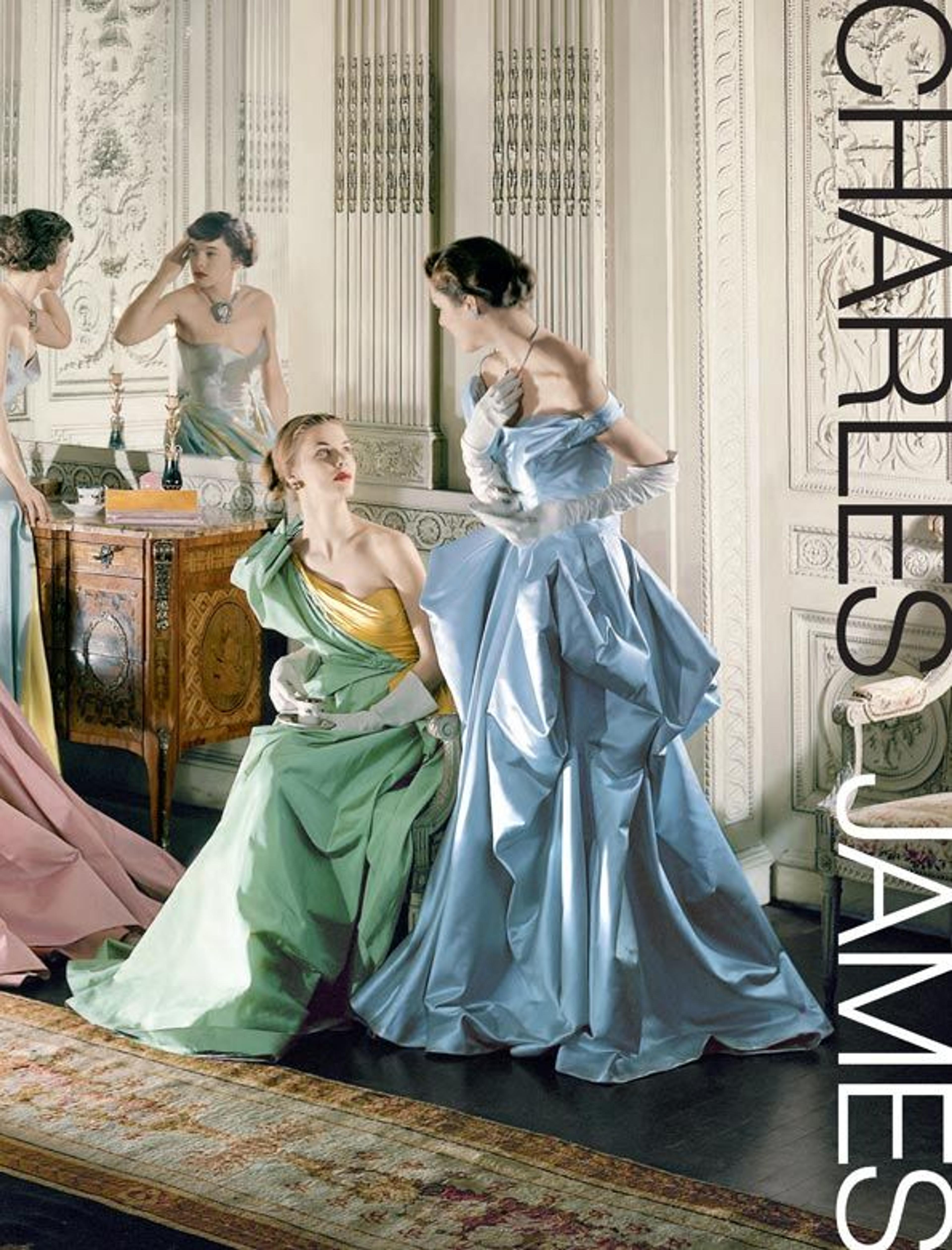

Charles James: Beyond Fashion, by Harold Koda and Jan Glier Reeder, with a preface by Ralph Rucci and contributions by Sarah Scaturro and Glenn Petersen, features 315 illustrations (273 in full color) and is available in The Met Store.

«The Costume Institute's 2014 exhibition, Charles James: Beyond Fashion, opens May 8 and offers a comprehensive study of the life and work of legendary Anglo-American couturier Charles James (1906−1978). In the accompanying exhibition catalogue, co-author Jan Glier Reeder—consulting curator in The Costume Institute for the Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art—highlights James's virtuosity and inventiveness, as well as his influence on future generations of fashion designers. This publication also includes early photographs and rarely seen archival items, such as muslin study pieces, dress forms, and sketches.»

I had the opportunity to speak with Reeder, who also serves as co-curator of the exhibition, about the publication and her fascination with America's first couturier, Charles James.

Rachel High: Charles James influenced many of today's well-known designers, including Cristóbal Balenciaga and Christian Dior, yet many may not have heard of him. Why do you think James is often overlooked, and what do you hope the catalogue will convey about this incredible designer's history that may have been lost?

Jan Reeder: One of my objectives for the book was to present the whole story of Charles James. Little work had been done regarding his early life and his time designing in London, and this book offers new information about these important formative years. James was a complicated person who loved creating myths about himself. These myths were perpetuated and his history became increasingly muddled, so I aimed to straighten out the facts as much as possible.

I also wanted to convey the range of techniques that he used—such as spiraling, draping, sculpting, and folding. James's fascination with the human anatomy was a continuous theme throughout his work, along with four constant concerns: fit, movement, eroticism, and sound structure. He really was "beyond fashion"; he was an artist and a creative being who chose working with cloth as his main medium of expression. He was idiosyncratic in his approach, and—even though it's a hackneyed word—there was a "genius" there, a creative genius that everyone who knew him noticed. Innumerable people used that term about him, and it was the one thing that I don't think he made up about himself.

James was prescient about so many things. I just had lunch with a woman who knew him well, and she had a great story to share. In the 1940s James had a wealthy client who had a mink coat, and he said, "We must do something about the vulgar patina of this mink!" He then took a pair of shears and sheared off the outer layer of the mink! This is one of many examples where he was the first to try something new; sheared mink didn't become popular until the 1960s. He did these outlandish things that later became mainstream. James always thought outside of the box and wasn't constricted by the normal dressmaking conventions, theories, or techniques.

Rachel High: When did you first become interested in Charles James, and how did you arrive at this exhibition and publication?

Jan Reeder: I was the director and curator of the Brooklyn Museum's costume-documentation project for three years, and we had about three hundred of his works in the collection. I also became immersed in James when I worked on the High Style exhibition and catalogue, and chose to devote a whole chapter to James.

Fortunately, in 2011, I participated in a curatorial exchange program between the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum and the Met. I had been thinking for some time that there were noticeable parallels and influences between Elsa Schiaparelli and James. The V&A has early works by James as well as wonderful Schiaparellis, so I spent a month at the V&A comparing Schiaparelli and James works from the 1930s. I also made side trips to the Brighton Museum and to Birr Castle in Ireland, where some of the very early James pieces still remain in private hands. James has been my main research focus since that time.

Photograph of Nancy and Charles James by Cecil Beaton, 1955. Courtesy of the Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby's

Rachel High: Could you speak about some of the innovative materials that Charles James used in his work?

Jan Reeder: He was at the forefront of the use and promotion of innovative textiles, and also utilized materials in crazy ways for which they weren't intended. Along with Elsa Schiaparelli, James was the first to use cellophane—a novelty transparent material also known as glasscloth—in fashionable clothing. He was also among the first to use a zipper in a dress, and certainly, along with Schiaparelli, the first to use zippers exposed as decoration. His "Taxi" dress of 1932 included a zipper covered with a large, obvious placket spiraled around the body. In the 1930s he developed four daytime-dress designs for a company that was an early innovator in producing fabric blends using wool and cotton.

James also designed evening wraps using completely unorthodox fabrics that included billiard cloth (the felt used for pool tables) and millinery grosgrain. The grosgrain was a narrow material, eighteen inches wide, used exclusively for making and supporting the foundations of hats. James, however, thought the material would be good for making garments that had a sculptural appearance, because its rigidity would hold the shape. So he made a voluminous evening cape, for instance, that required twenty pattern pieces and twenty-four yards of the material to make. The company that had produced the grosgrain subsequently expanded their looms to weave larger widths of it. He also promoted rayon, a synthetic silk that was just gaining credibility for use in evening wear.

Later, in the 1940s and '50s, James promoted the newest synthetics, pellon and nylon. Pellon is a stiff, non-woven synthetic that became widely used for petticoats and the linings of bouffant evening dresses and cocktail dresses during the 1950s. He was one of the first to use the material in that way, and mixed it with other stiffening materials to support some of his grand ball gowns. James even fashioned dramatic drapery from it for his elegant showroom on 57th Street—something only a designer capable of thinking outside of the box would do.

Rachel High: What is your favorite piece featured in the catalogue?

Jan Reeder: That's really tough, it's like asking who your favorite child is—they're all favorites for different reasons. One dress is an early one from 1937 that belonged to the Countess of Rosse. She was one of James's early clients, and we are very lucky to have been able to borrow three of her pieces from her family. The bustle effect is created by a huge swoosh of fabric. The idea that there is this asymmetrical shape sticking out of the back was so unthinkable at that time. Designers of the time just wouldn't do that, and reminds me of Rei Kawakuba's explorations in outré bustle shapes.

I also think that the eiderdown coat is really extraordinary. The actual construction logistics of putting this together were diabolical. James only made one, and he knew he was only going to make one because of the difficulty—but again, that was the idea. James was creating wearable art; he was creating sculpture, a soft sculpture. Of course you can't talk about favorites without mentioning the Four Leaf Clover gown, it's simply extraordinary. There's a reason for its iconic status: It is the ultimate in glamorous, show-stopping evening wear.

Left: Charles James (American, born Great Britain, 1906–1978). "Coq Noir" Evening Dress, 1937. Silk. Courtesy of Sir Brendan Parsons, seventh Earl of Rosse, Birr Castle, Ireland

Rachel High: The Four Leaf Clover gown was recreated for a press presentation about the exhibition. What did you learn about the piece from its recreation?

Jan Reeder: The idea was for the model, Elettra Wiedemann, to feel what it was like to wear the gown and to move in it. She said that it slightly pulled her forward, which was interesting because Austine Hearst, for whom the dress was originally created, noted that it was quite balanced on the hips. What impressed me was that Wiedemann captured the posture and the look of other women who were photographed wearing it. She was transformed and she felt that.

Rachel High: The exhibition is opening this week and the catalogue is being released just before Mother's Day. The book has some absolutely gorgeous images of the outfits and sumptuous detail images of the fabrics. My colleagues and I think it makes a perfect gift for anyone interested in the history of fashion, and an especially good Mother's Day gift to visit the exhibition and purchase the text.

Jan Reeder: It would be a beautiful Mother's Day gift. The cover has just captivated everybody. One thing I wish for the catalogue is that it serves several purposes. I hope the scholarship in it will be used to expand the topic and give the book a good, solid base. The chapter at the end on conservation, "Inherent Vice," is so rare, and that enriches the book tremendously. The authors of that chapter, Sarah Scaturro and Glenn Peterson, are very talented conservators, and there aren't two people who could write better on that topic. But I also think it is a beautiful coffee-table book. I was also happy that we could incorporate Charles James's voice throughout the book. We thought, "How are we going to do that? Can we add all the editorial images? Can we get the quotes in? Can we get captions on the editorial images?" There were all of these stages of creation involved in the process.

Austine Hearst in Charles James "Four Leaf Clover" Gown, ca. 1953. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photographer Unknown, © Bettmann/CORBIS

Related Link

The Met Store: Charles James: Beyond Fashion