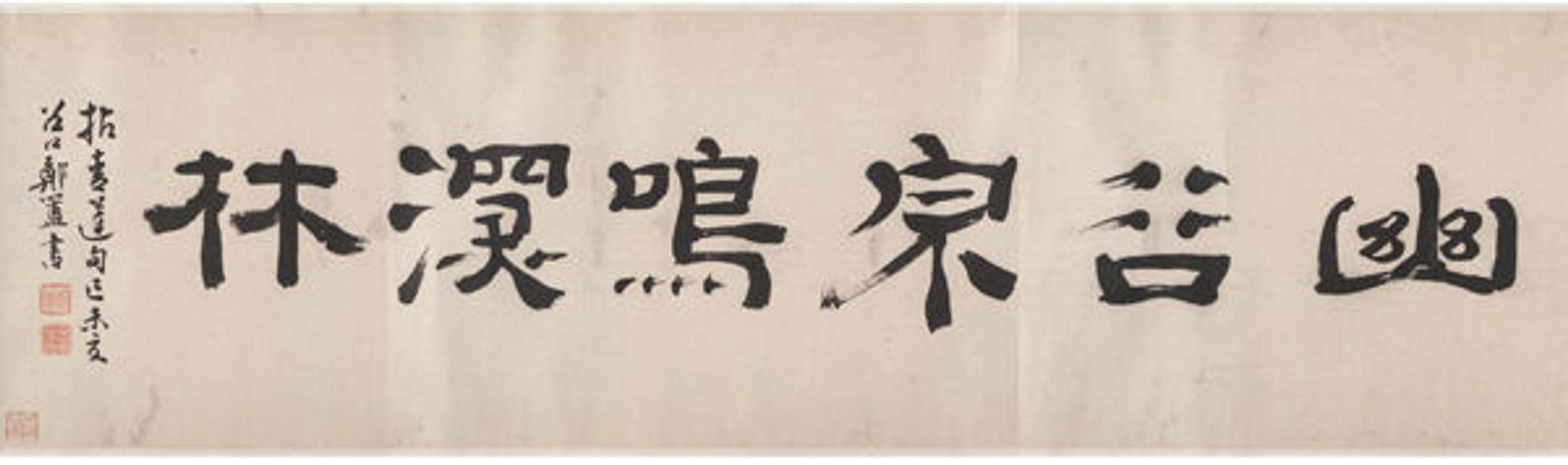

Fig. 1. Zheng Fu (Chinese, 1622–1694), for Liu Yu (Chinese, 1620–after 1689). Remote Valleys and Deep Forests (frontspiece detail), dated 1678, frontspiece dated 1679. Handscroll, ink and color on paper; 10 5/8 x 144 1/8 in. (27 x 366 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Promised Gift of Marie-Hélène and Guy Weill Family (L.2002. 24.1) (Not on view)

«"The Administrator of Kuaiji [Wang Xizhi, ca. 303–ca. 361] is all mannerist cliché.

As the study of calligraphy declines, I enjoy a free rein with a laugh.

Scornful of following known calligraphers like a maid,

I take the stone tablet of Mount Hua as my master."

In 1736, leading artist Jin Nong (1687–1773) wrote this iconoclastic quatrain that reflects a momentous turning point in the development of Chinese calligraphy during his time. Abandoning the venerated tradition defined by the classic elegance of its patriarch, Wang Xizhi, Jin Nong turned to an earlier, less-sophisticated model—stone inscriptions of the ancient Han dynasty (206 b.c.–a.d. 220)—for guidance.» Carved from the works of unknown calligraphers not self-consciously making art, Han inscriptions exude fresh vitality in a natural and plain manner. Generations of calligraphers after Jin Nong further integrated the stylistic characteristics of bronze inscriptions that hark back to the second millennium b.c. and stone inscriptions of the Northern Dynasties (386–581). Collectively known as the Epigraphic School, these artists dominated the final chapter of the calligraphic evolution of dynasty China. Several of its greatest exponents are featured in the current exhibition Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy—Selections from the Collection of Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang, on view through August 17.

This new trend started in the late seventeenth century—not long after the conquest of China by the alien Manchus in 1644—when calligraphers actively sought out Han dynasty steles and emulated the distinctive style of the engraved texts, as best exemplified by the life and art of its foremost initiator, Zheng Fu (fig. 1). The dynastic change sent ethnic Han calligraphers into a nostalgic rediscovery of China's antiquity, from which inscribed Han steles were treasured artifacts. The advocacy of archaic writings from anonymous hands also gestured defiance against the Manchu regime which, from the emperor down, favored the Wang Xizhi tradition. More importantly, the return to Han models represented a pursuit of authenticity.

Genuine autograph works of Wang Xizhi and other old masters were lost long ago; successive copies and rubbings of their calligraphy, intended to preserve and transmit their art, served instead to adulterate their essence. An ancient stele, on the other hand, preserves the writing of its time without eons of human mediation, while natural cracks and abrasions on the surface add to its emotive as well as visual appeal.

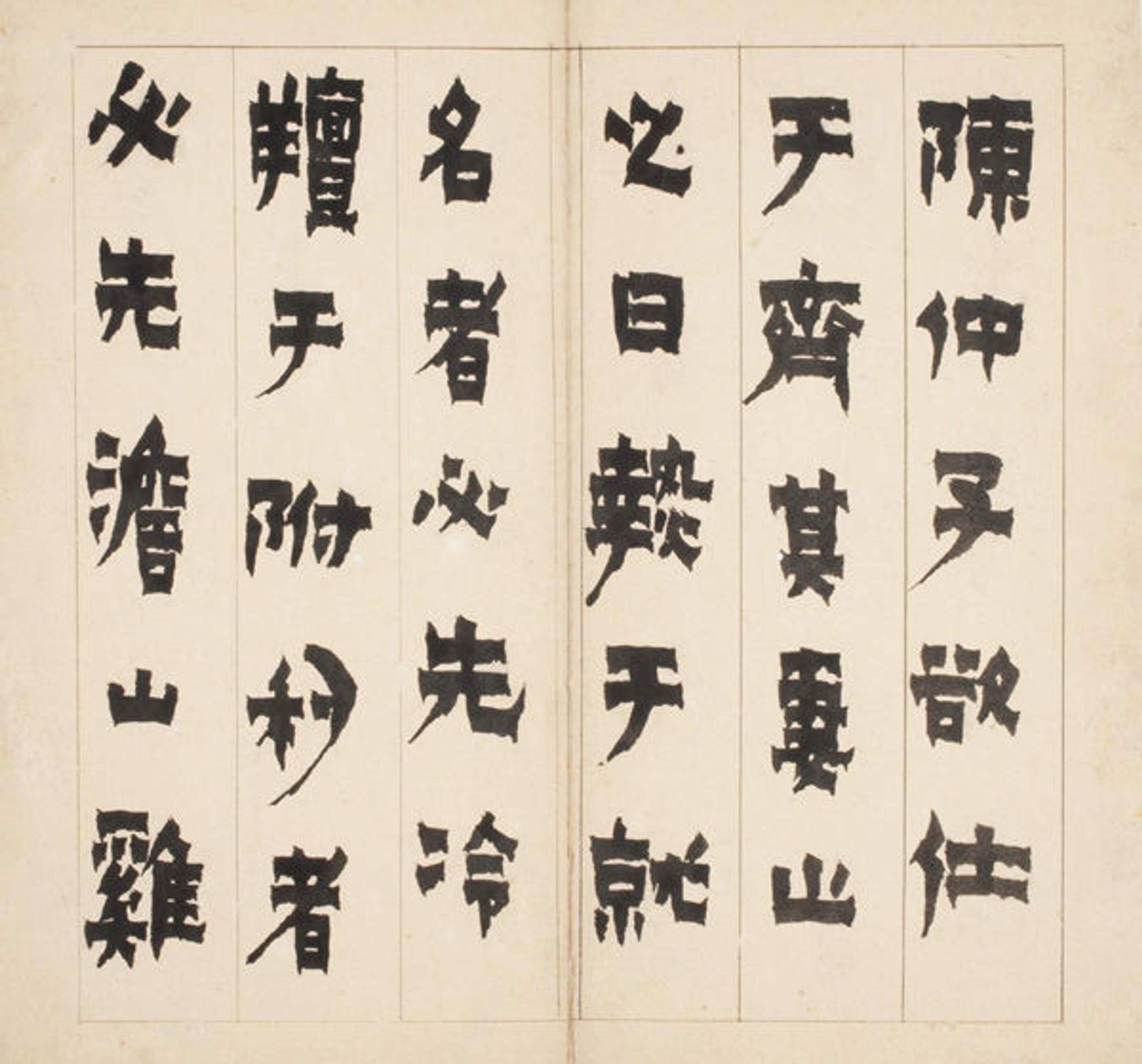

Fig. 2. Jin Nong (Chinese, 1687–1773). The Story of Chen Zhongzi, dated 1749. First of nine leaves from an album of nineteen leaves, ink on paper; each page: 12 1/4 x 6 1/4 in. (31.1 x 15.9 cm); overall (open): 12 1/4 x 12 3/8 in. (31.1 x 31.4 cm). Lent by Guanyuan Shanzhuang Collection

Grounded on the stately Han stele inscriptions that feature a squat configuration of characters with angular corners and gracefully modulated horizontal and diagonal strokes, the new aesthetic blossomed in the metropolis of Yangzhou in the eighteenth century, with Jin Nong heralded as one of its most creative champions (fig. 2). Jin's calligraphy, as he notes in his poem, grew out of Han steles, but transformed his source material beyond recognition. He created a unique "lacquer script" for his tall characters that, in their extreme angularity and spikiness, appear as knife-work more than brushwork. Uninhibited self-expression connoted emotional authenticity, even when he, like many other artists in this mercantile entrepôt, frankly addressed his material desires.

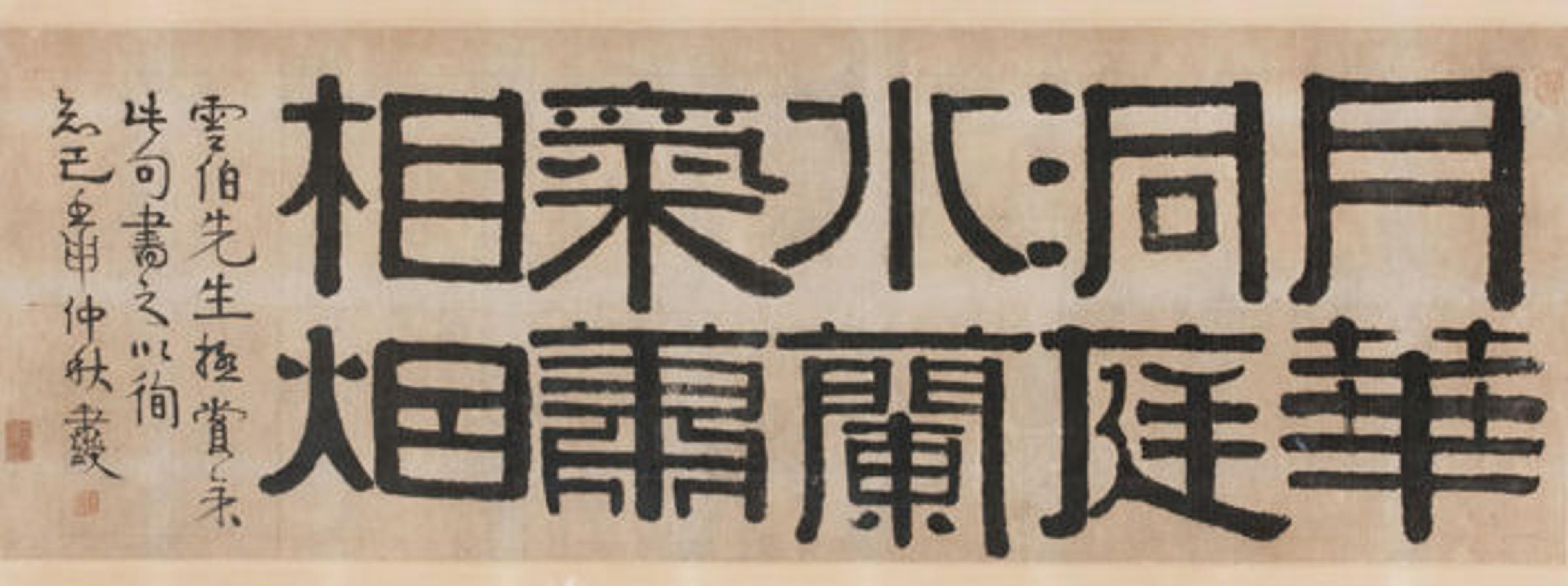

Fig. 3. Yi Bingshou (Chinese, 1754–1815). Poetic Couplet, dated 1812. Framed horizontal scroll, ink on paper; 13 1/8 x 38 in. (33.3 x 96.5 cm). Lent by Guanyuan Shanzhuang Collection

Later masters of the Epigraphic School shunned both Zheng Fu's revivalist ideal and Jin Nong's unrecognizable reinvention—but not because they chose to walk a safer middle way; for them it was simply more fun to play with the rules, bending them rather than casting them off. As individualists, their authenticity of expression brought motley splendor to the climactic ending of the movement. Yi Bingshou's poetic couplet was written primarily in the style of Han steles, but the verticality of the characters and the uniform width of each brush stroke are traits of pre-Han bronze inscriptions (fig. 3). The varied size and placement of the characters resonates with the lack of exactitude in ancient writings and animates the gridlike format with a sense of gentle motion that echoes the couplet, "Moonlight on the waters of Lake Dongting / Orchid fragrance in the mists over the Xiao and Xiang Rivers."

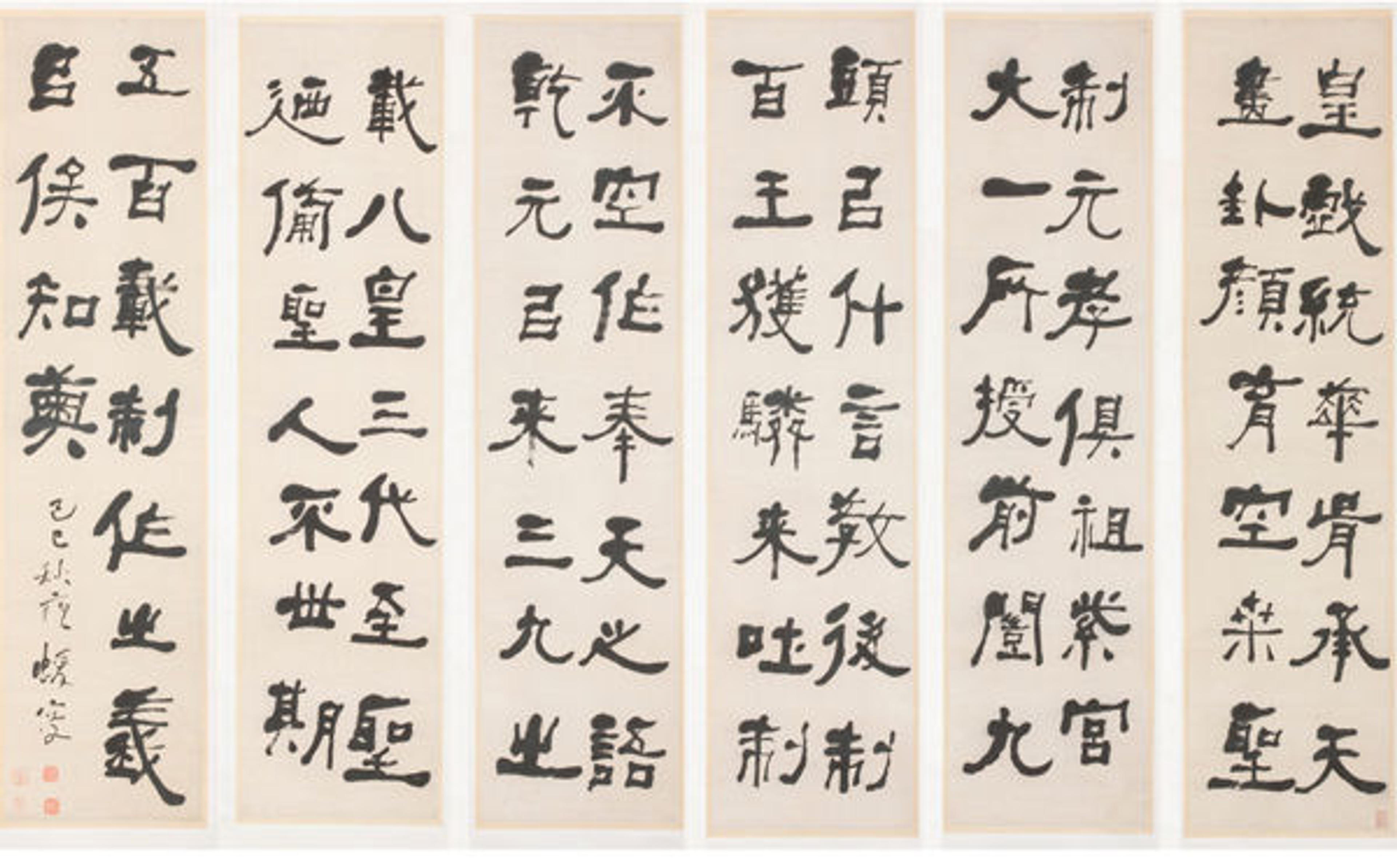

Fig. 4. He Shaoji (Chinese, 1799–1873). Stele on Renovating a Confucian Temple and Its Ritual Implements, dated 1869. Set of six hanging scrolls, ink on paper; each scroll: 53 1/2 x 13 1/8 in. (135.9 x 33.3 cm); overall: 79 1/8 x 17 3/4 in. (201 x 45.1 cm). Promised gift of Guanyuan Shanzhuang Collection

He Shaoji's partial transcription of the text on the famous Han dynasty Stele on Ritual Implements is an intriguing puzzle (fig.4). One of his favorite models, he copied it up to a hundred times in his life; however, this rendering, far from a faithful copy, does something different. The characters tend to lean to the right rather than stand up straight. The thickening and thinning of the under-articulated brush strokes show no apparent logic. Although the character structures in the original are often discernible, the blotches, awkward twists, and rough-edged lines are He's quirky variations. Monumental in scale, the work evokes writings in a disappearing act on crumbly, blemished walls, replete with the mystery of an artifact from antiquity.

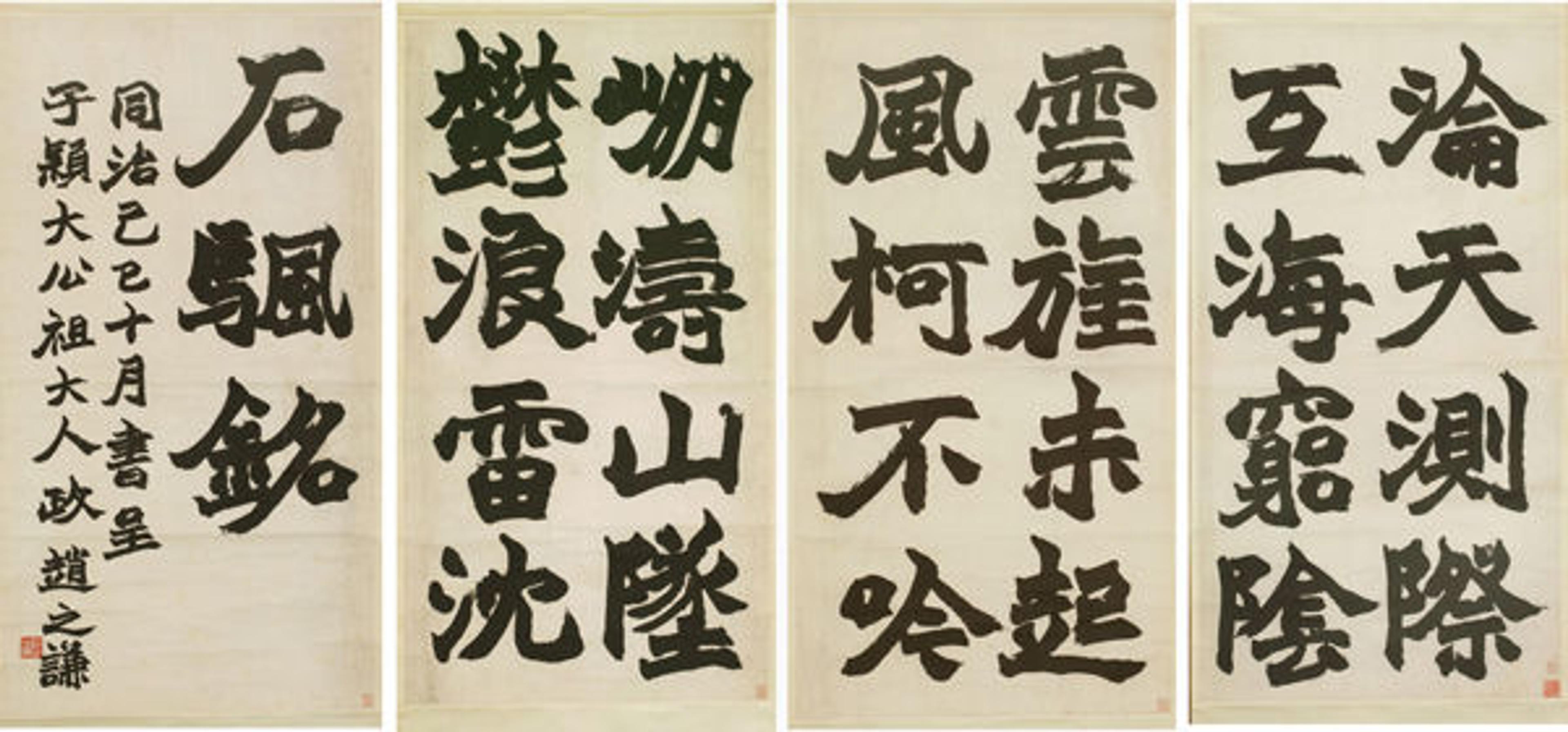

Fig. 5. Zhao Zhiqian (Chinese, 1829–84). Inscription on Stone Sails, dated 1869. Set of four hanging scrolls, ink on paper; each scroll: 38 1/4 x 20 3/8 in. (97.2 x 51.8 cm). Promised gift of Guanyuan Shanzhuang Collection

While He Shaoji's calligraphy feels like human markings scarred, and graphically enriched, by the accidental in nature, the powerful physicality of Zhao Zhiqian's partial transcription of Bao Zhao's (ca. 412–466) Inscription on Stone Sails—an ode to a mountain in Hunan with pointed peaks rising above cloud waves like sails on the ocean—conjures permanence (fig. 5). Modeled after the stone engravings of the Northern Dynasties, the angular and incisive brush strokes recall the working of a carving knife. Their bold thrusts and uniform dark tone give the piece a majestic presence.

The Northern Dynasties were ruled by nomads from the steppes. As native Chinese culture declined, stylized Han stele calligraphy gave way to a new trend favoring simplified brush manners and dynamic structures more in tune with the raw and virile nomadic spirit. One and a half millennia later, Zhao Zhiqian and his colleagues appeared to detect in the calligraphy of a lesser culture authentic manifestations of primal humanity.