In the 1870s a young Alphonse J. Lespinasse arrived in Mérida, Campeche, Mexico, to begin his term as United States consul. In those days, the Yucatán Peninsula was a volatile place, having been the scene of a political rebellion known as the Caste War of Yucatán, which began in the late 1840s. (In fact, one of the outcomes of the conflict was that peoples of Maya descent formed the independent nation of Chan Santa Cruz in the modern state of Quintana Roo, and even established diplomatic relations with Mexico and the United Kingdom.) Lespinasse arrived in the middle of a tense situation between native Yukatek Maya speakers and landowners who were largely foreigners, or criollos, of European descent.

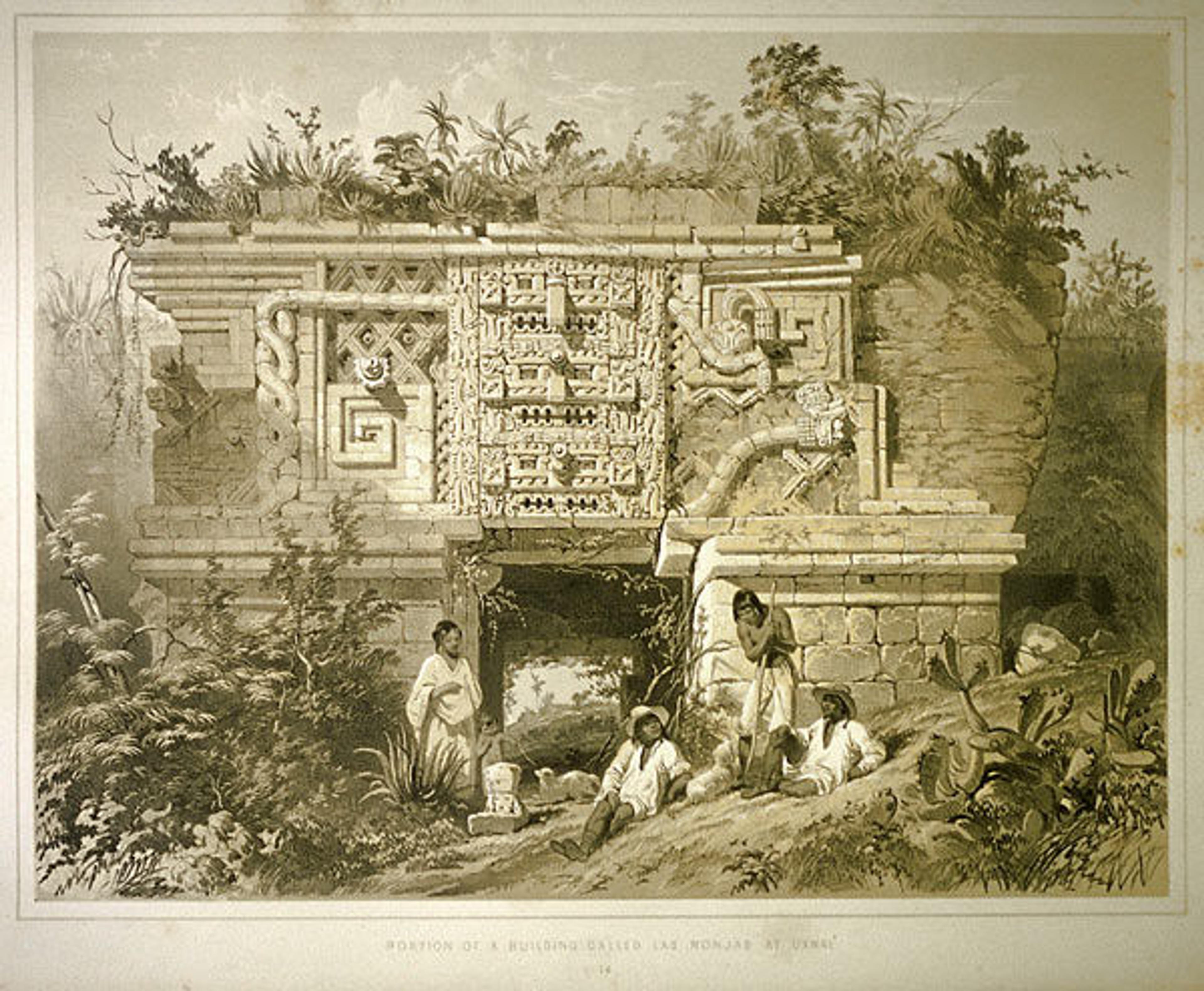

The Yucatán was also gaining fame in the nineteenth century as the setting for the florescence of ancient Maya civilization. The widely read account Incidents of Travel in Yucatán, published in 1843 by John Lloyd Stephens with illustrations by Frederick Catherwood, thrust the plant-covered ruins of Maya cities such as Chichen Itza and Uxmal into the spotlight of popular culture (fig. 1). These abandoned cities in the northern Yucatán had always formed an integral part of the social landscape, and were included in descriptions and images from the earliest surviving Spanish colonial documents. In particular, the site of Uxmal caught the attention of scholars and travelers alike with its exceptionally well-preserved standing architecture, covered with complex sculpted mosaics showing images of rulers, serpents, and other animate creatures.

Fig. 1. "Portion of a Building Called Las Monjas at Uxmal," by Frederick Catherwood, from Incidents of Travel in Yucatán, 1843

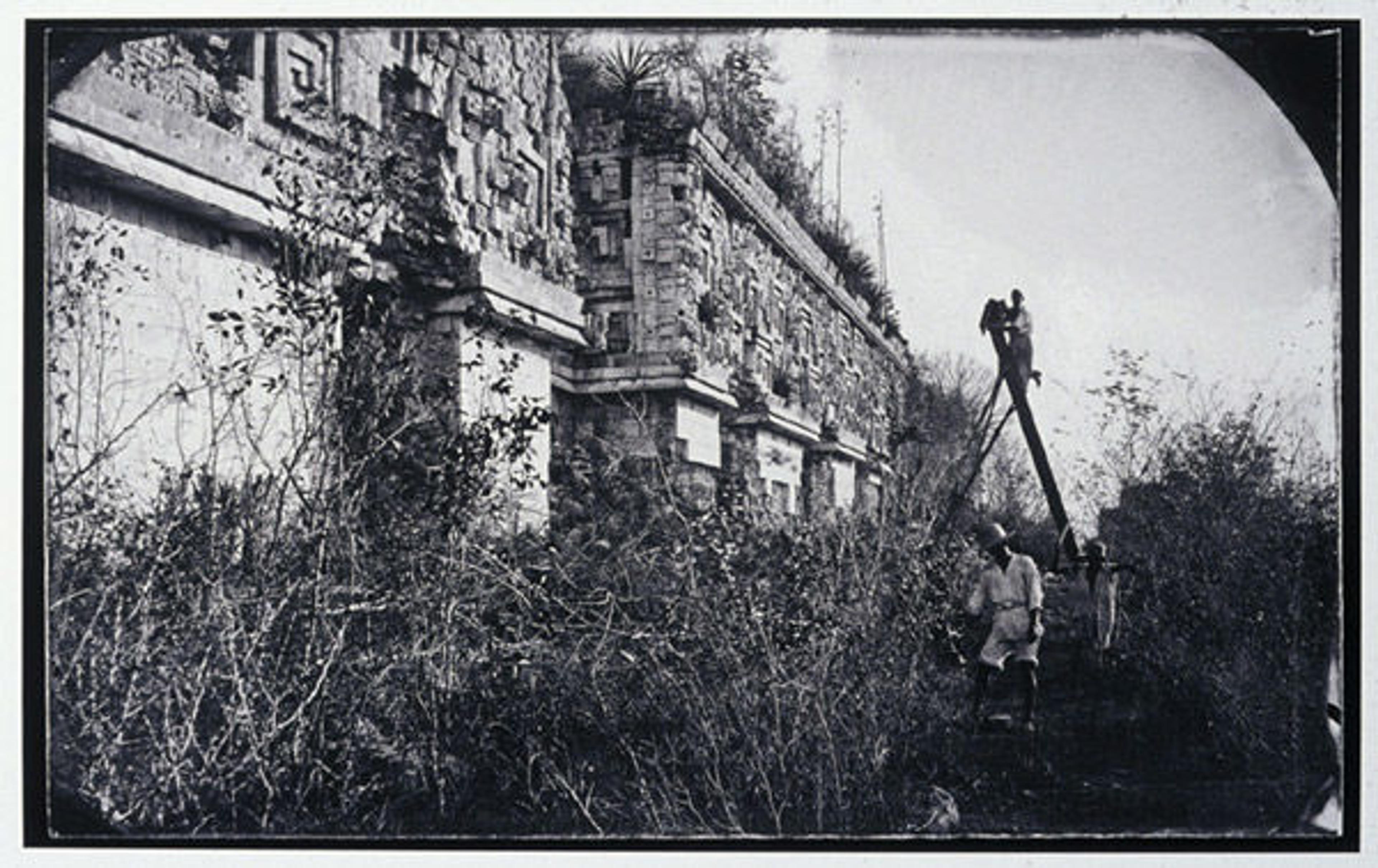

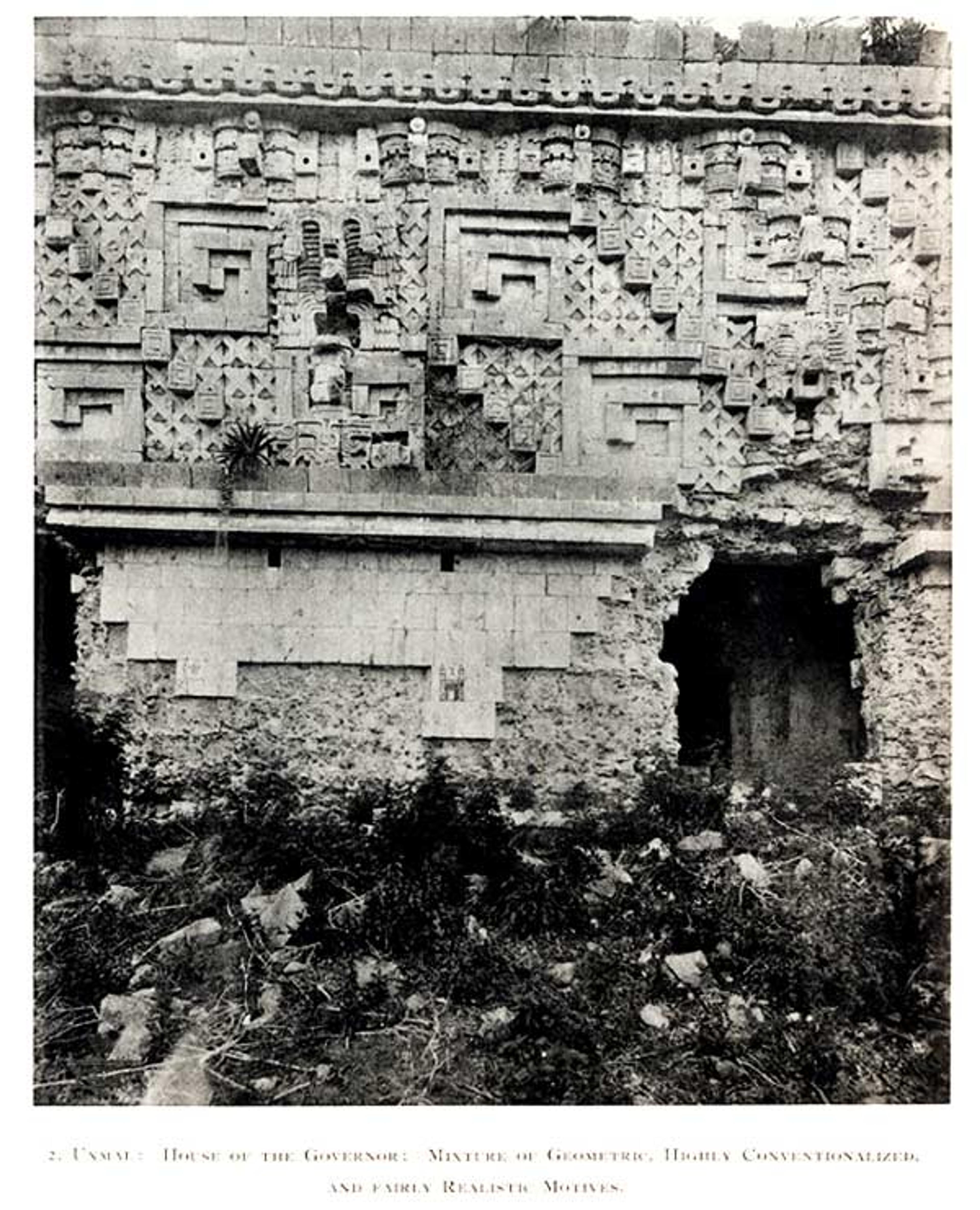

By the time Lespinasse began his diplomatic post, Uxmal was well known in Mexico and abroad. Many early historians of the ancient Maya besides Stephens and Catherwood visited and recorded the ruins of Uxmal in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, including Jean-Frédéric Waldeck (1838), Claude-Joseph Désiré Charnay (1862–63, 1885), Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg (1865), Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon (1873–81), William Henry Holmes (1895), and Eduard Seler (1917). The visits of Charnay and the Le Plongeons to Uxmal were pivotal in the recording of Maya art and architecture, as they were the first to successfully photograph the ruins, which pioneered the way for later photographic methods (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Augustus Le Plongeon photographing the ruins of Uxmal on a ladder. Photograph by Alice Dixon LePlongeon, ca. 1873. Getty Research Institute (2004.M.18-b15.18)

In a letter to his brother, Alphonse Lespinasse offered an architectural fragment from Uxmal to the fledgling Metropolitan Museum, not yet at its current Fifth Avenue location:

General S. H. and myself have just returned from a trip to the ruined city of Uxmal some 40 miles distant from Merida and by this steamer you will receive a stone which comes from the largest and most important building in Uxmal.

This building is known as the "Casa del Gobernador." It is an imposing ruin situate [sic] on the top of three terraces, and is some 320 feet in length, the building is very minutely and well described in "Stephens Yucatán."

The stone as you will see is a key stone, and belonged to one of the arches of the doors of the Palace.

As to the origin of these ruins I can say nothing the natives have no traditions concerning them. The designs on the stone represent hieroglyphics somewhat similar to those of the ancient Egyptians. It is to be hoped that some day their secrets will be revealed and will throw a new light on the early civilization of America. As this is I believe the only specimen of these ruins ever sent to New York. If you think it of enough importance send the stone to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it may prove of interest to the students of early American Art.

I enclose a photograph of the "Casa del Gobernador," a better picture of the ruins you will find in "Stephens Yucatán."

Signed A. J. Lespinasse

U.S. Consul

Merida, Mexico

The House of the Governor (Casa del Gobernador) received its name from a seventeenth-century Spanish visitor who named the Uxmal buildings after European counterparts; the Pyramid of the Magician, the Nunnery Quadrangle, and the House of the Pigeons are other nicknames. The sculpted block sent by Lespinasse to New York is carved in deep relief and shows an upside-down u-shaped element terminating in volutes on either side (fig. 3). Inside the negative space of the central shape rise three discs with indentations. Rising from the volutes on either side are two loop-like shapes, and below the center is trapezoidal protrusion flanked by deep arch-shaped voids. The main bulk of the stone behind the relief is long and tapered, similar to other sculptures intended to be inserted into walls as tenoned decoration.

Fig. 3. Fragmentary Relief, 9th–10th century. Uxmal, Yucatán, Mexico, Mesoamerica. Stone; H. 6 1/2 x W. 14 1/2 in. (16.51 x 36.83 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of A. J. Lespinasse, 1877 (77.8)

Both Lespinasse and his brother, who offered the stone to the Metropolitan Museum on his behalf, noted that the stone was similar to a keystone at the summit of an arch. A reanalysis of the architectural sculpture recorded at Uxmal in the years after the consul's original visit, however, reveals that the Met's block formed part of a monumental mosaic "mask," an anthropomorphic portrait of a mountain deity, or witz in Mayan.

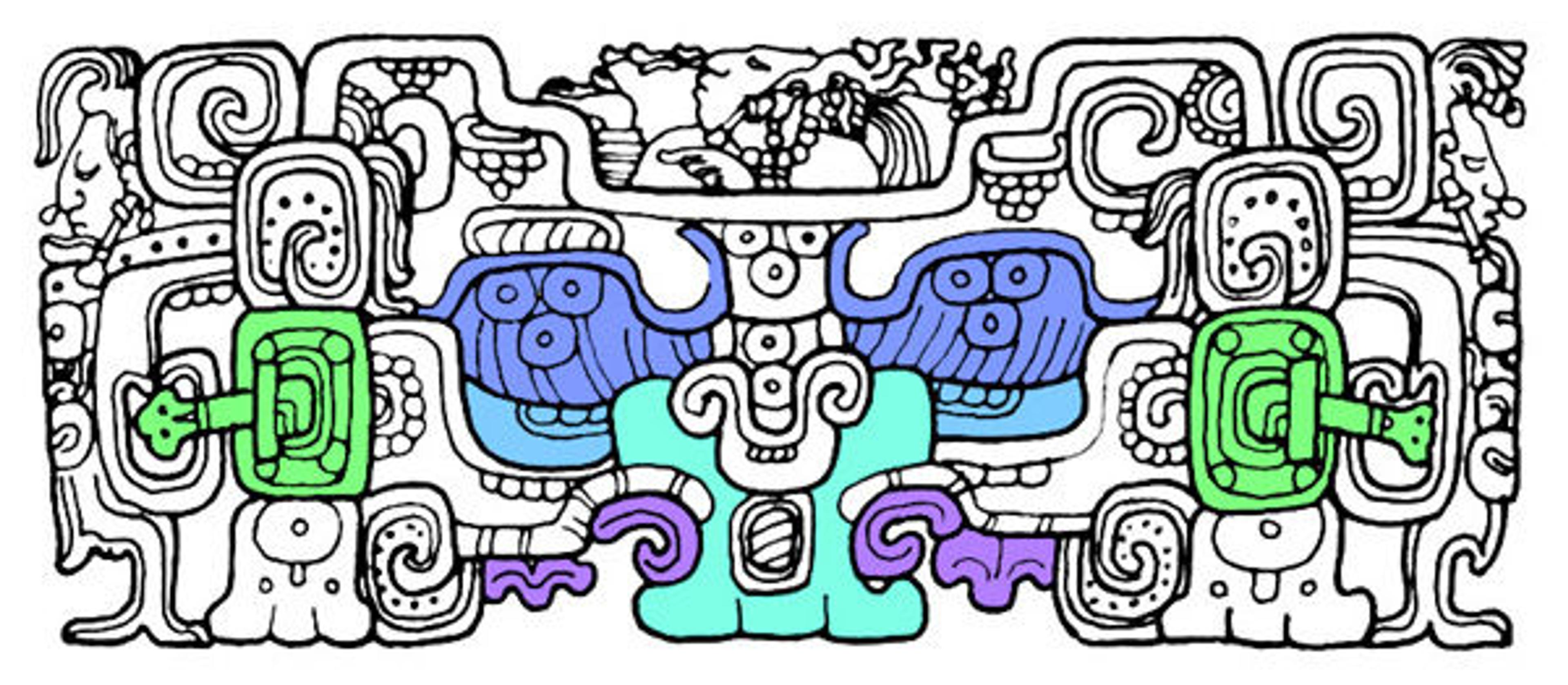

Mountains were central to Lowland Maya cosmology; the ancient Maya actually viewed their pyramidal buildings as mountains from which water and sustenance emerged. Accordingly, the builders of ancient Maya temples and carvers of ancient Maya sculptures marked architecture and places with what is known as the witz monster. These fantastic creatures are often portrayed with enlarged snouts and gaping jaws which represented overhangs and watery caves beneath mountains. On stelae, kings and queens often stand atop witz monsters, signaling their powers to mediate between the realm of mountainous nature and the human world (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Drawing of witz monster Bonampak Stela 1, by Linda Schele. © David Schele. The mountain deity's eyes are in light blue, the eyelids and brows are in dark blue, the snout is in teal, the teeth in violet, and the jade ear flares worn by the mountain are in green. The Maya maize god emerges from the stepped cleft in the mountains head (see "The Drinking Cup of a Classic Maya Noble" for another example of maize god emergence).

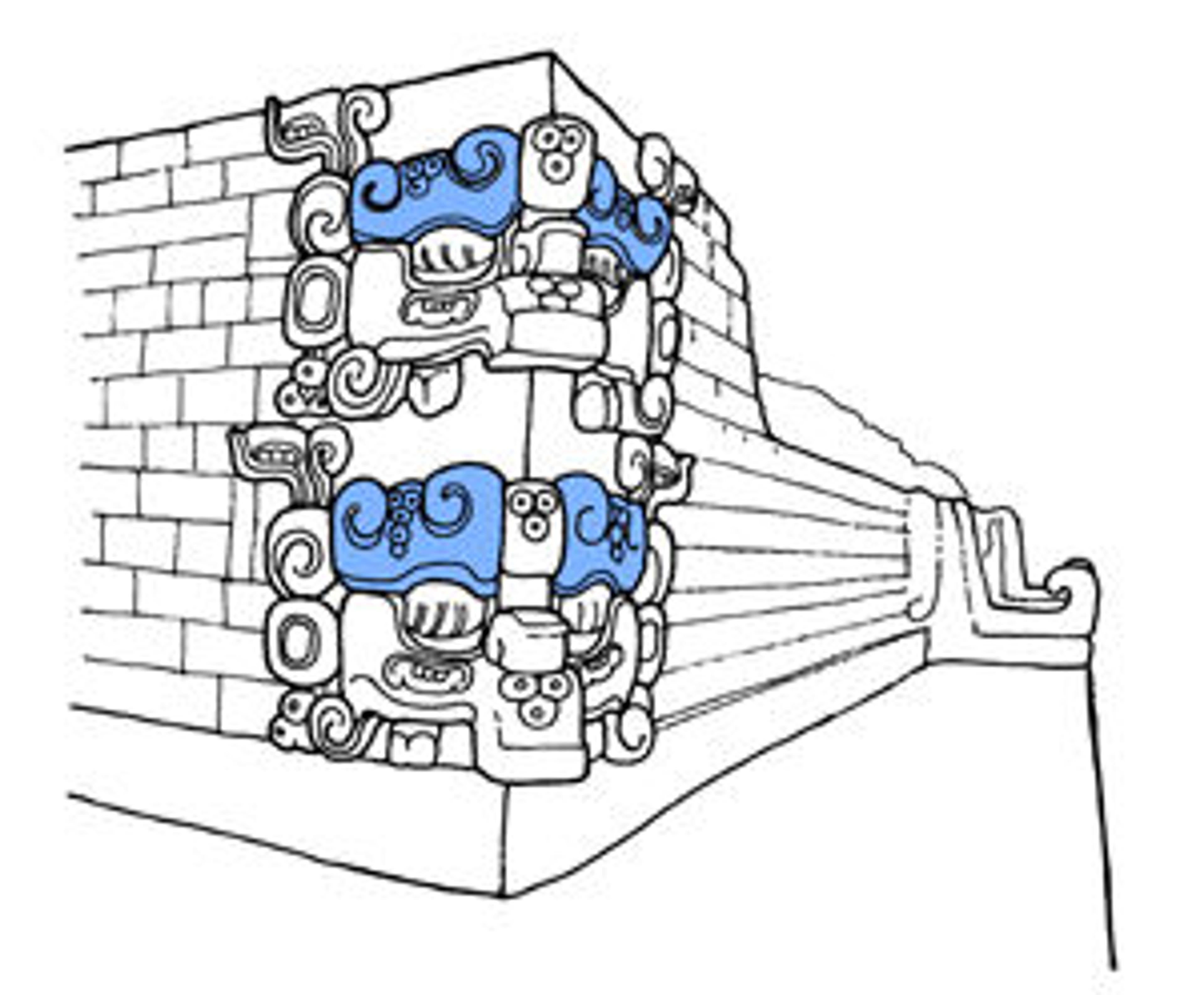

Rather than creating one giant sculptured portrait of the witz monster, which would have been difficult and structurally unsound, Maya architects often created a series of stacked portraits in the corners of buildings. This approach allowed visitors to such a building to behold multiple mountain faces from all directions, thus underscoring the sacred nature of the constructed temple. The style of stacking witz heads is especially prevalent in the late eighth and ninth centuries, from such distant city-states as Copan, Honduras (fig. 5), and Uxmal itself.

Left: Fig. 5. Reconstruction of witz monster sculptures, Structure 22, Copan, Honduras, by Linda Schele. © David Schele. The monsters' eyebrows are highlighted in blue.

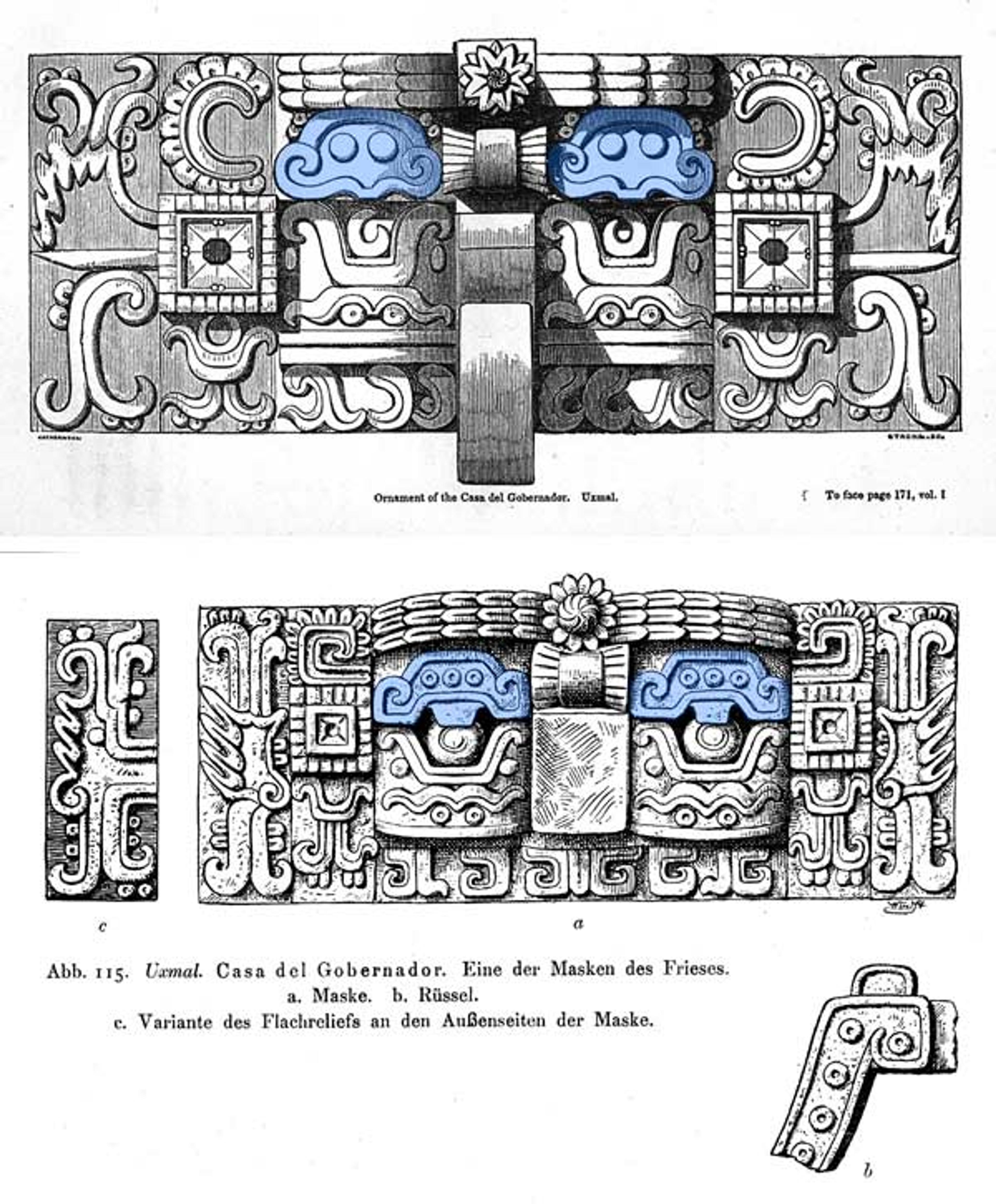

Returning to the Met's fragment reportedly from the House of the Governor, it probably came from a collapsed witz monster portrait, such as the many documented in situ on the façades at Uxmal. The Stephens 1843 publication includes Catherwood's drawing of such an ornamented portrait. A rendering of the same portrait, described as "one of the masks of the frieze," included in Seler's 1917 publication on Uxmal contains more accurate representations of the proportions and details of each piece of the sculpture (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Drawings of witz monster mask, House of the Governor, Uxmal, by Frederick Catherwood (Top: from John L. Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Yucatán, facing p. 171; Bottom: Eduard Seler, "Die Ruinen von Uxmal," fig. 115). Eyebrows are highlighted in blue.

The 1913 Spinden photograph of the unrestored façade and a close-up picture of the modern consolidated façade confirm that the Met's fragment was likely embedded as the eyebrow and pendant lid of a witz portrait (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Façade, House of the Governors, Uxmal. Top: from Herbert J. Spinden, "A Study of Maya Art, Its Subject Matter and Historical Development" (Pl. 8, No. 2); Bottom: from Charles S. Rhyne, Architecture, Restoration, and Imaging of the Maya Cities of Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil, and Labná

Maya artists and sculptors at Uxmal mixed geometric designs reminiscent of woven textiles with conventionalized and naturalistic portraiture to transform a palace building within a mountainless landscape into a mythological mountainous location for courtly life and ritual. Doing so cast the kings and queens of Uxmal as providers, voices in the liminal space between the natural and the manmade.

Resources and Additional Reading

Barrera Rubio, Alfredo, and José Huchím Herrera. Architectural Restoration at Uxmal, 1986–1987. University of Pittsburgh Latin American Archaeology Reports No. 1. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Department of Anthropology, 1990.

Brasseur de Bourbourg, Charles-Étienne. "Rapport sur les ruines de Mayapan et d'Uxmal au Yucatán (Mexique)." Archives de la Commission Scientifique du Méxique, Vol. 2 (1865): 234–288. Paris: Imprimerie Impériale.

Catherwood, Frederick. Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán. London: Publisher, 1944.

Charnay, Joseph Désiré. Cités et Ruines Américaines. Paris: A. Morel, 1863.

Foncerrada de Molina, Marta. La escultura arquitectónica de Uxmal. Mexico: Imprenta Universitaria, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1965.

Holmes, William H. "Archaeological Studies among the Ancient Cities of Mexico, Publication 8." Anthropological Series, Vol. 1, No.1, Part I, "Monuments of Yucatán." Chicago: Field Museum, 1895.

Kowalski, Jeff K. House of the Governor: A Maya Palace at Uxmal, Yucatán, Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

Pillsbury, Joanne, ed. Past Presented: Archaeological Illustration and the Ancient Americas. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2012.

Rhyne, Charles S. Architecture, Restoration, and Imaging of the Maya Cities of Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil, and Labná, 2008. http://academic.reed.edu/uxmal/

Schele, Linda. Linda Schele Drawing Collection. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc, 2000. http://research.famsi.org/schele.html

Seler, Eduard. "Die Ruinen von Uxmal." Abhandlungen der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, Nr. 3. Berlin: Verlag der Königl. Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1917.

Sellen, Adam T., and Lynneth S. Lowe. "Las antiguas colecciones arqueológicas de Yucatán en el Museo Americano de Historia Natural." Estudios de Cultura Maya, No. 33 (2009): 53–71. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/ecm/v33/v33a3.pdf

Spinden, Herbert J. "A Study of Maya Art, Its Subject Matter and Historical Development." Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Vol. VI. Cambridge: Peabody Museum, 1913.

Stephens, John L. Incidents of Travel in Yucatán. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1843.

Stone, Andrea, and Marc Zender. Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2011.

Stuart, David, and Evon Z.Vogt. "Some Notes on Ritual Caves among the Ancient and Modern Maya." In the Maw of the Earth Monster: Mesoamerican Ritual Cave Use, James E. Brady and Keith M. Prufer, eds. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005.