![Abraham Entertaining the Angels from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac [Left: front; Right: back]. Flemish, ca. 1600 (41.100.57e)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/d30f3932e0c501390f3472ce2ca07f195d84ce64-600x303.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Left: "Abraham Entertaining the Angels" from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac, ca. 1600. Flemish. Wool, silk, silver-gilt thread; 19 3/4 x W. 20 in. (50.2 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.100.57e). Right: "Abraham Entertaining the Angels" from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac (view of back)

«Many #tapestrytuesday readers have asked why some tapestries in the Met's collection have such diverse color palettes. As it turns out, the question you should be asking isn't "Why?" but "Dye?" Understanding the preservation or degradation of a tapestry's color is a complex sort of query whose answer is largely influenced by the dyes used to color its threads. To help unravel the mystery of tapestry colors, I recently sat down for a fascinating lesson in dyeing with two of the Museum's tapestry experts: Cristina Carr, conservator in the Department of Textile Conservation; and Nobuko Shibayama, associate research scientist in the Department of Scientific Research.»

Sarah Mallory: So what makes a tapestry so colorful?

Nobuko Shibayama: Light and dyes.

Sarah Mallory: I had suspected that had something to do with it. How exactly do light and dye make a tapestry's color?

Cristina Carr: The great variation in a tapestry's color was achieved by combining relatively few dyes [also called dyestuffs] and mordants [metallic salts derived from a variety of sources]. These different components were then applied to either animal [wool or silk] or vegetable [linen] fibers. These fibers may have already been spun into thread and then dyed. The range of colors in a tapestry depend on how a particular fiber reacted to the dyestuff.

Sarah Mallory: Even just one tapestry must contain many different combinations of dyes and threads, which would mean that each tapestry's colors end up looking a little bit different. But what about light? How does that influence a tapestry's color?

Nobuko Shibayama: Light has no color itself; it is actually an electromagnetic wave that comes in a variety of wavelengths. When the spectrum of light waves hits the dye molecules in a tapestry's thread, the thread either absorbs or reflects the light. This reflected light is recognized by the human eye and brain as a specific color. The chemical structure of a dye ultimately determines which light waves are absorbed and which are reflected.

Sarah Mallory: I see—but sometimes a tapestry's colors fade. Why does this happen?

Cristina Carr: Environmental factors such as light, temperature, humidity, and particulate matter [dust] cause changes in the molecules that give a dye its color. The longer a tapestry's threads are exposed to these factors, the more it will fade.

Nobuko Shibayama: Minute iron particles in dust or dirt, as well as high relative humidity, can also speed up the fading process.

Sarah Mallory: Since every tapestry has lived a different life and is made of different dyes and threads, it makes sense that some pieces will retain their colors better than others. Is there anything you can do to reverse the effects of fading on a tapestry?

Cristina Carr: The effects resulting from exposure to environmental factors are cumulative and not reversible. Any time a tapestry is exposed to light and air, it is at risk for fading.

Nobuko Shibayama: Exactly, this fading happens on a molecular level. When a tapestry's threads absorb light, the energy of this light brings the dye molecule to an excited state.

Sarah Mallory: Excited state?

Nobuko Shibayama: Yes, moving very quickly.

Sarah Mallory: Oh, I see—like stirring red glitter into a pitcher of water? The more glitter you add, and the more energy you put into stirring the glitter quickly, the more the glitter will move around and make the water appear red.

Nobuko Shibayama: Yes, but this energy doesn't last forever. The dye molecule can lose some of the energy through a reaction with other molecules such as oxygen, which is referred to as photo-oxidation.

Sarah Mallory: So, in other words, if I pour some particles—let's say marbles—into the glitter water, the glitter will stop moving so quickly and begin to sink to the bottom of the pitcher, and eventually the water will not look red anymore. I would also never be able to stir the water in the pitcher and recreate the same glittery red color because the marbles permanently changed the composition of the pitcher's contents.

Nobuko Shibayama: Yes. In photo-oxidation, the parts of the dye molecule responsible for creating color react with oxygen and lose their specific color-producing structure, which then results in a loss of color, otherwise known as fading. The reaction is catalyzed by the presence of a certain type of [transition] metals such as iron, but not all metals necessarily lead to fading. High moisture content in the fibers comprising the tapestry's threads can also catalyze photo-oxidation.

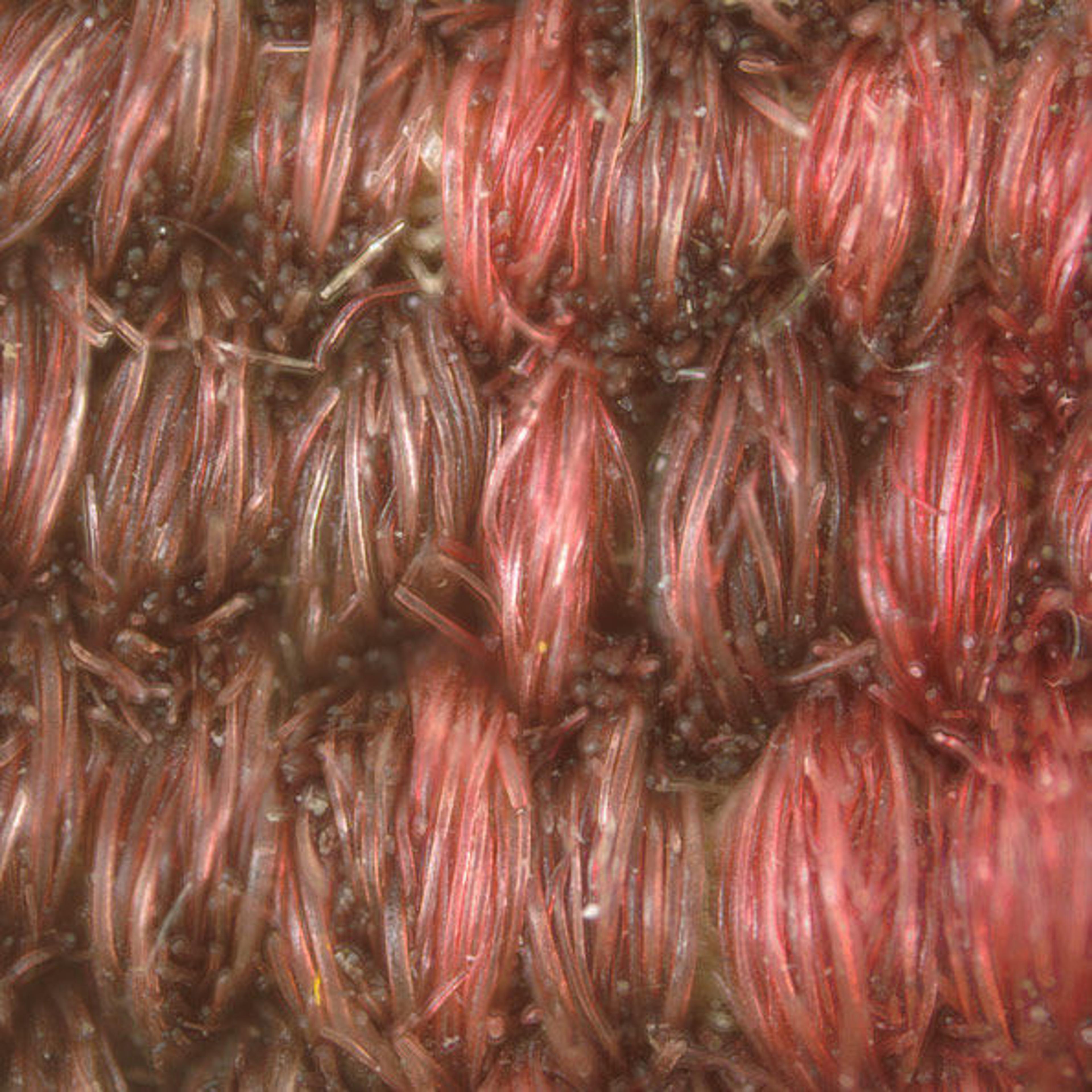

Detail of red thread from "Abraham Entertaining the Angels" from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac, magnified fifty times. Photo by Cristina Balloffet Carr © Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sarah Mallory: Why are there metals in thread fibers? I know tapestries can include metal-wrapped threads, but I always thought tapestries were made of silk, wool, or linen?

Cristina Carr: Funnily enough, the metals come from the mordants in the dyes. Before the eighteenth century, dyes were derived from organic materials such as plants, insects, and shellfish . . .

Nobuko Shibayama: . . . such as leaves of the indigo plant for blue dyes, roots of the madder plant or bodies of cochineal [an insect] for red dyes, and a secretion from some types of shellfish for purple dyes.

Cristina Carr: The metals are introduced in the mordants, which are salts that enhance the sometimes weak chemical reaction between fiber and dyestuff. In other words, mordants help the dye stick to the fiber, and also help create different shades and hues of colors.

Cochneal insects used to make red dyes

Sarah Mallory: Who made all of these dyes?

Nobuko Shibayama: Master craftsman who belonged to dyers guilds made dyes and dyed fabrics, in addition to a few individual dyers or artisans who were outstanding master dyers or specialists. Farmers or gatherers usually collected the plants, insects, or other raw materials needed for the dyestuffs. The seventeenth century saw the unprecedented development of new, formal scientific processes. Chemists applied these newly formed modes of inquiry to the study and development of dyes and the dyeing process. After the middle of the eighteenth century, dye chemists and synthetic-dye factories started to take over the position of the dyers who used natural products. Chemists then began producing synthetic dyes using coal tar.

Sarah Mallory: Thank you for sharing the basics of tapestry dyes. Where can we learn more about the subject?

Cristina Carr: From August 4, 2014, through Jan 18, 2015, the Antonio Ratti Textile Center here at the Met will feature detailed information about dyes and samples of dyestuffs, as well as magnified images of dyed threads as part of Examining Opulence: A Set of Renaissance Tapestry Cushions. Visitors will also have the rare opportunity to see the backs of six luxurious tapestry-woven cushion covers. Since the back of a tapestry is only occasionally exposed to light, the colors are well preserved. In the case of these cushions, the colors are extremely bright and seem shockingly modern, though these pieces are more than four centuries old.

"Dye Analysis of Medieval Tapestry Yarns," from Redemption: Tapestry Preservation Past and Present—a symposium in honor of the Burgos Tapestry Christ is Born as Man's Redeemer in the collection of The Cloisters. Recorded December 8, 2009